Lightning Detection Methods and Meteorological Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Observation of the Lightning Induced Variations in Atmospheric Ions

XV International Conference on Atmospheric Electricity, 15-20 June 2014, Norman, Oklahoma, U.S.A. The Observation of the Lightning Induced Variations in Atmospheric Ions Xuemeng Chen1,*, Hanna E. Manninen1,2, Pasi Aalto1, Petri Keronen1, Antti Mäkelä3, Jussi Paatero3, Tuukka Petäjä1 and Markku Kulmala1 1. Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 2. Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, Estonia 3. Finnish Meteorological Institute, Helsinki, Finland ABSTRACT: Variations in atmospheric ion concentration were studied in a boreal forest in Finland, with emphasis on the effect of lightning. In general, changes in ion concentrations have diurnal and seasonal patterns. Distinct features were found in ions of different size ranges, namely small ions (0.8 – 1.7 nm) and intermediate ions (1.7 – 7 nm). Preliminary results on two case studies of lightning effect are present, one with rain effect and the other not. Bursts in the concentrations of small ions and intermediate ions were observed in both cases. However, different trends in trace gases were observed for the two cases. Further investigation is needed to reveal the nature of lightning ions and the mechanism in their formation. The work is under progress. INTRODUCTION Atmospheric ions, or air ions, refer to electric charge carriers present in the atmosphere. Distinct features exist in their chemical composition, mass, size as well as number of carried charges. According to Tammet [1998], atmospheric ions can be classified into small or cluster ions, intermediate ions, and large ions based on their mobility (Z) in air, being Z > 0.5 cm2V-1s-1, 0.5 cm2V-1s-1 ≤ Z ≥ 0.03 cm2V-1s-1 and Z< 0.03 cm2V-1s-1, respectively. -

![The Error Is the Feature: How to Forecast Lightning Using a Model Prediction Error [Applied Data Science Track, Category Evidential]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5685/the-error-is-the-feature-how-to-forecast-lightning-using-a-model-prediction-error-applied-data-science-track-category-evidential-205685.webp)

The Error Is the Feature: How to Forecast Lightning Using a Model Prediction Error [Applied Data Science Track, Category Evidential]

The Error is the Feature: How to Forecast Lightning using a Model Prediction Error [Applied Data Science Track, Category Evidential] Christian Schön Jens Dittrich Richard Müller Saarland Informatics Campus Saarland Informatics Campus German Meteorological Service Big Data Analytics Group Big Data Analytics Group Offenbach, Germany ABSTRACT ACM Reference Format: Despite the progress within the last decades, weather forecasting Christian Schön, Jens Dittrich, and Richard Müller. 2019. The Error is the is still a challenging and computationally expensive task. Current Feature: How to Forecast Lightning using a Model Prediction Error: [Ap- plied Data Science Track, Category Evidential]. In Proceedings of 25th ACM satellite-based approaches to predict thunderstorms are usually SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’19). based on the analysis of the observed brightness temperatures in ACM, New York, NY, USA, 10 pages. different spectral channels and emit a warning if a critical threshold is reached. Recent progress in data science however demonstrates 1 INTRODUCTION that machine learning can be successfully applied to many research fields in science, especially in areas dealing with large datasets. Weather forecasting is a very complex and challenging task requir- We therefore present a new approach to the problem of predicting ing extremely complex models running on large supercomputers. thunderstorms based on machine learning. The core idea of our Besides delivering forecasts for variables such as the temperature, work is to use the error of two-dimensional optical flow algorithms one key task for meteorological services is the detection and pre- applied to images of meteorological satellites as a feature for ma- diction of severe weather conditions. -

6.4 the Warning Time for Cloud-To-Ground Lightning in Isolated, Ordinary Thunderstorms Over Houston, Texas

6.4 THE WARNING TIME FOR CLOUD-TO-GROUND LIGHTNING IN ISOLATED, ORDINARY THUNDERSTORMS OVER HOUSTON, TEXAS Nathan C. Clements and Richard E. Orville Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 1. INTRODUCTION shear and buoyancy, with small magnitudes of vertical wind shear likely to produce ordinary, convective Lightning is a natural but destructive phenomenon storms. Weisman and Klemp (1986) describe the short- that affects various locations on the earth’s surface lived single cell storm as the most basic convective every year. Uman (1968) defines lightning as a self- storm. Therefore, this ordinary convective storm type will propagating atmospheric electrical discharge that results be the focus of this study. from the accumulation of positive and negative space charge, typically occurring within convective clouds. This 1.2 THUNDERSTORM CHARGE STRUCTURE electrical discharge can occur in two basic ways: cloud flashes and ground flashes (MacGorman and Rust The primary source of lightning is electric charge 1998, p. 83). The latter affects human activity, property separated in a cloud type known as a cumulonimbus and life. Curran et al. (2000) find that lightning is ranked (Cb) (Uman 1987). Interactions between different types second behind flash and river flooding as causing the of hydrometeors within a cloud are thought to carry or most deaths from any weather-related event in the transfer charges, thus creating net charge regions United States. From 1959 to 1994, there was an throughout a thunderstorm. Charge separation can average of 87 deaths per year from lightning. Curran et either come about by inductive mechanisms (i.e. al. also rank the state of Texas as third in the number of requires an electric field to induce charge on the surface fatalities from 1959 to 1994, behind Florida at number of the hydrometeor) or non-inductive mechanisms (i.e. -

Climatic Information of Western Sahel F

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Clim. Past Discuss., 10, 3877–3900, 2014 www.clim-past-discuss.net/10/3877/2014/ doi:10.5194/cpd-10-3877-2014 CPD © Author(s) 2014. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 10, 3877–3900, 2014 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Climate of the Past (CP). Climatic information Please refer to the corresponding final paper in CP if available. of Western Sahel V. Millán and Climatic information of Western Sahel F. S. Rodrigo (1535–1793 AD) in original documentary sources Title Page Abstract Introduction V. Millán and F. S. Rodrigo Conclusions References Department of Applied Physics, University of Almería, Carretera de San Urbano, s/n, 04120, Almería, Spain Tables Figures Received: 11 September 2014 – Accepted: 12 September 2014 – Published: 26 September J I 2014 Correspondence to: F. S. Rodrigo ([email protected]) J I Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 3877 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract CPD The Sahel is the semi-arid transition zone between arid Sahara and humid tropical Africa, extending approximately 10–20◦ N from Mauritania in the West to Sudan in the 10, 3877–3900, 2014 East. The African continent, one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change, 5 is subject to frequent droughts and famine. One climate challenge research is to iso- Climatic information late those aspects of climate variability that are natural from those that are related of Western Sahel to human influences. -

Datasheet: Thunderstorm Local Lightning Sensor TSS928

Thunderstorm Local Lightning Sensor ™ TSS928 lightning Vaisala TSS928™ is a local-area lightning detection sensor that can be integrated with automated surface weather observations. Superior Performance in Local- area TSS928 detects: Lightning Tracking • Optical, magnetic, and electrostatic Lightning-sensitive operations rely on pulses from lightning events with zero Vaisala TSS928 sensors to provide critical false alarms local lightning information, both for • Cloud and cloud-to-ground lightning meteorological applications as well as within 30 nautical miles (56 km) threat data, to facilitate advance • Cloud-to-ground lightning classified warnings, initiate safety procedures, and into three range intervals: isolate equipment with full confidence. • 0 … 5 nmi (0 … 9 km) The patented lightning algorithms of TSS928 provide the most precise ranging • 5 … 10 nmi (9 … 19 km) of any stand-alone lightning sensor • 10 … 30 nmi (19 … 56 km) available in the world today. • Cloud-to-ground lightning classified The optical coincident requirement into directions: N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, Vaisala TSS928™ accurately reports the eliminates reporting of non-lightning and NW range and direction of cloud-to-ground events. The Vaisala Automated lightning and provides cloud lightning TSS928 can be used to integrate counts. Lightning Alert and Risk Management lightning reports with automated (ALARM) system software is used to weather observation programs such as visualize TSS928 sensor data. METAR. Technical Data Measurement Performance Support Services Detection range 30 nmi (56 km) radius from sensor Vaisala TSS928™ is fully supported by our Customer location Support Center, Technical Service Group, and Field Range resolution Three range groups: Service Engineering Team. Maintain optimal 0 … 5 nmi (0 … 9 km) performance by purchasing a service agreement 5 … 10 nmi (9 … 19 km) customized to your unique system requirements. -

Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit

SEVERE THUNDERSTORMS AND TORNADOES TOOLKIT A planning guide for public health and emergency response professionals WISCONSIN CLIMATE AND HEALTH PROGRAM Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health dhs.wisconsin.gov/climate | SEPTEMBER 2016 | [email protected] State of Wisconsin | Department of Health Services | Division of Public Health | P-01037 (Rev. 09/2016) 1 CONTENTS Introduction Definitions Guides Guide 1: Tornado Categories Guide 2: Recognizing Tornadoes Guide 3: Planning for Severe Storms Guide 4: Staying Safe in a Tornado Guide 5: Staying Safe in a Thunderstorm Guide 6: Lightning Safety Guide 7: After a Severe Storm or Tornado Guide 8: Straight-Line Winds Safety Guide 9: Talking Points Guide 10: Message Maps Appendices Appendix A: References Appendix B: Additional Resources ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Wisconsin Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit was made possible through funding from cooperative agreement 5UE1/EH001043-02 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the commitment of many individuals at the Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS), Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health (BEOH), who contributed their valuable time and knowledge to its development. Special thanks to: Jeffrey Phillips, RS, Director of the Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health, DHS Megan Christenson, MS,MPH, Epidemiologist, DHS Stephanie Krueger, Public Health Associate, CDC/ DHS Margaret Thelen, BRACE LTE Angelina Hansen, BRACE LTE For more information, please contact: Colleen Moran, MS, MPH Climate and Health Program Manager Bureau of Environmental and Occupational Health 1 W. Wilson St., Room 150 Madison, WI 53703 [email protected] 608-266-6761 2 INTRODUCTION Purpose The purpose of the Wisconsin Severe Thunderstorms and Tornadoes Toolkit is to provide information to local governments, health departments, and citizens in Wisconsin about preparing for and responding to severe storm events, including tornadoes. -

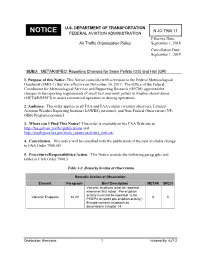

METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION N JO 7900.11 NOTICE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION Effective Date: Air Traffic Organization Policy September 1, 2018 Cancellation Date: September 1, 2019 SUBJ: METAR/SPECI Reporting Changes for Snow Pellets (GS) and Hail (GR) 1. Purpose of this Notice. This Notice coincides with a revision to the Federal Meteorological Handbook (FMH-1) that was effective on November 30, 2017. The Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research (OFCM) approved the changes to the reporting requirements of small hail and snow pellets in weather observations (METAR/SPECI) to assist commercial operators in deicing operations. 2. Audience. This order applies to all FAA and FAA-contract weather observers, Limited Aviation Weather Reporting Stations (LAWRS) personnel, and Non-Federal Observation (NF- OBS) Program personnel. 3. Where can I Find This Notice? This order is available on the FAA Web site at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and http://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices/. 4. Cancellation. This notice will be cancelled with the publication of the next available change to FAA Order 7900.5D. 5. Procedures/Responsibilities/Action. This Notice amends the following paragraphs and tables in FAA Order 7900.5. Table 3-2: Remarks Section of Observation Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Volcanic eruptions must be reported whenever first noted. Pre-eruption activity must not be reported. (Use Volcanic Eruptions 14.20 X X PIREPs to report pre-eruption activity.) Encode volcanic eruptions as described in Chapter 14. Distribution: Electronic 1 Initiated By: AJT-2 09/01/2018 N JO 7900.11 Remarks Section of Observation Element Paragraph Brief Description METAR SPECI Whenever tornadoes, funnel clouds, or waterspouts begin, are in progress, end, or disappear from sight, the event should be described directly after the "RMK" element. -

Analysis of Lightning and Precipitation Activities in Three Severe Convective Events Based on Doppler Radar and Microwave Radiometer Over the Central China Region

atmosphere Article Analysis of Lightning and Precipitation Activities in Three Severe Convective Events Based on Doppler Radar and Microwave Radiometer over the Central China Region Jing Sun 1, Jian Chai 2, Liang Leng 1,* and Guirong Xu 1 1 Hubei Key Laboratory for Heavy Rain Monitoring and Warning Research, Institute of Heavy Rain, China Meteorological Administration, Wuhan 430205, China; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (G.X.) 2 Hubei Lightning Protecting Center, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-27-8180-4905 Received: 27 March 2019; Accepted: 23 May 2019; Published: 1 June 2019 Abstract: Hubei Province Region (HPR), located in Central China, is a concentrated area of severe convective weather. Three severe convective processes occurred in HPR were selected, namely 14–15 May 2015 (Case 1), 6–7 July 2013 (Case 2), and 11–12 September 2014 (Case 3). In order to investigate the differences between the three cases, the temporal and spatial distribution characteristics of cloud–ground lightning (CG) flashes and precipitation, the distribution of radar parameters, and the evolution of cloud environment characteristics (including water vapor (VD), liquid water content (LWC), relative humidity (RH), and temperature) were compared and analyzed by using the data of lightning locator, S-band Doppler radar, ground-based microwave radiometer (MWR), and automatic weather stations (AWS) in this study. The results showed that 80% of the CG flashes had an inverse correlation with the spatial distribution of heavy rainfall, 28.6% of positive CG (+CG) flashes occurred at the center of precipitation (>30 mm), and the percentage was higher than that of negative CG ( CG) − flashes (13%). -

Incident Management Situation Report Wednesday, August 2, 2000 - 0530 Mdt National Preparedness Level V

INCIDENT MANAGEMENT SITUATION REPORT WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 2, 2000 - 0530 MDT NATIONAL PREPAREDNESS LEVEL V CURRENT SITUATION: Dry lightning and very heavy initial attack activity occurred in Arizona, southern New Mexico, southern California, Nevada and Utah. Many of the new starts are unstaffed. Seventeen new large fires were reported in the Western and Eastern Great Basin, Northern Rockies, Southern California, and Southern Areas. An Area Command Team was mobilized to Northern Rockies Area. One Type I Incident Management Team was mobilized to Nevada, one was mobilized to the Eastern Great Basin Area and one was reassigned within the Northern Rockies Area. Containment goals were reached on three large fires. Numerous aircraft, equipment, crew and overhead resource orders are being processed by the National Interagency Coordination Center. All eleven western states are reporting very high to extreme fire danger indices. EASTERN GREAT BASIN AREA LARGE FIRES: Priorities are being established by the Great Basin Multi-Agency Coordinating Group based on information submitted via Wildfire Situation Analysis reports and Incident Status Summary (ICS-209) forms. LOGAN COMPLEX, Wasatch-Cache National Forest. A Type II Incident Management Team (Carr) is assigned. This complex is comprised of the High Point (600 acres) and the Millville 2 (160 acres) fires, both located near Logan, UT. The Millville is a new fire that was ignited on 7/31 near the town of Millville. Helicopters are doing bucket work to support the suppression effort. OLDROYD COMPLEX, Fishlake National Forest. A Type I Incident Management Team (Hutchinson) is assigned. This complex includes the Oldroyd, Mona West, Broad, Mourning Dove and Yance fires near Richfield, UT. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Cloud Flash Lightning Characteristics for Tornadoes Without Cloud-To-Ground Lightning

Melick, C.J, A.R. Dean, J.L. Guyer, and I.L. Jirak: Cloud Flash Lightning Characteristics for Tornadoes without Cloud-to-Ground Lightning. Preprints, 41st Natl. Wea. Assoc. Annual Meeting, Norfolk, VA, Natl. Wea. Assoc. –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Cloud Flash Lightning Characteristics for Tornadoes without Cloud-to-Ground Lightning CHRISTOPHER J. MELICK Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, University of Oklahoma NWS Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma ANDREW R. DEAN, JARED L. GUYER, ISRAEL L. JIRAK NWS Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma ABSTRACT The Storm Prediction Center (SPC) has traditionally utilized cloud-to-ground (CG) lightning to identify thunderstorm development and the potential for severe weather occurrence. Still, recent evidence has shown that tornadoes do sometimes occur in situations where CG flashes are absent. In the last few years, cloud flash (CF) data as part of total (CG + CF) lightning has been available at SPC from the Earth Networks Total Lightning Network (ENTLN). The current study examined United States tornado events that were not associated with CG lightning for the time period during which CF lightning data were available. The purpose of this examination was to provide some basic characteristics and environmental conditions of no-CG tornado reports with an emphasis on the relationship to CF activity using lightning data from the ENTLN. CG lightning was absent in about 2% (66) of all tornadoes during a three year period (2013-2015) with a significant portion of these rated as EF0. Unexpectedly, though, only 17% (11) of no-CG tornado reports occurred with CF, thus implying that total lightning was often lacking in these tornadic storms as well. -

B-100063 Cloud-Seeding Activities Carried out in the United States

WASHINGXJN. O.C. 205.48 13-100063 Schweikcr: LM096545 This is in response to your request of September 22, .2-o 1971, for certain background informatio-n on cloud-seeding activities carried out -...-in _-..T---*the .Unitc.b_S~.~-~,.under programs supported-by the Federal agencies. Pursuant to the specific xz2- questions contained in your request, we directed our:review toward developing information-----a-=v-~ .,- , L-..-”on- .-cloud-seeding ,__ ._ programs sup- ported by Federal agencies, on the cost- ‘and purposes of such progrys, on the impact of cloud seeding on precipitation and severe storms, and on the types of chemicals used for seeding and their effect on the--environment. We also ob- tained dafa cdncerning the extent of cloud seeding conducted over Pennsylvania. Our review was conducted at various Federal departments ’ and agencies headquartered in Washington, D.C., and at cer- tain of their field offices in Colorado and Montana. We in- terviewed cognizant agency officials and reviewed appropriate records and files of the agencies. In addition, we reviewed pertinent reports and documentation of the Federal Council for Science and Technology, the National Academy of Sciences, and the National Water Commission. BACKGROUND AND COST DATA Several Federal agencies support weather modification programs which involve cloud-seeding activities. Major re- search programs include precipitation modification, fog and cloud modification, hail suppression, and lightning and hur- ricane modification. Statistics compiled by the Interdepartmental Committee for Atmospheric Sciences showed that costs for federally spon- sored weather modification rograms during fiscal years 1959 through 1970 totaled about %‘74 million; estimated costs for fiscal years 1971 and 1972 totaled about $35 million.