In the 1530S, Shortly Before the Dissolution in 1539, Durham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 Christopher Thomas Daly College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Daly, Christopher Thomas, "Basilisks of the Commonwealth: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625366. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-y42p-8r81 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BASILISKS OF THE COMMONWEALTH: Vagrants and Vagrancy in England, 1485-1553 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts fcy Christopher T. Daly 1986 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts . s F J i z L s _____________ Author Approved, August 1986 James L. Axtell Dale E. Hoak JamesEL McCord, IjrT DEDICATION To my brother, grandmother, mother and father, with love and respect. iii TABLE OE CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................. v ABSTRACT.......................................... vi INTRODUCTION ...................................... 2 CHAPTER I. THE PROBLEM OE VAGRANCY AND GOVERNMENTAL RESPONSES TO IT, 1485-1553 7 CHAPTER II. -

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

Black British History Tudors & Stuarts Ad 1485 - 1714

A TIMELINE OF BLACK BRITISH HISTORY TUDORS & STUARTS AD 1485 - 1714 The Tudor and Stuart periods saw monumental change in the relationship between Europe and their continental neighbours. As the period begins, we see evidence of integrated societies at different levels of local and national life. By the close, Britain is embarked on a frenzied mission to extend their colonial reach and primed to step into an industrial revolution, powered by the outrageous wealth accumulation made possible by the triangular slave trade. THE COURT OF JAMES IV AD 1488 - 1513 King James IV Scotland had numerous qualities and successes; he united the highlands and lowlands; he created a Scottish navy; and maintained alliances with France and England. It is clear that he was also something of a forerunner in regards multi-culturalism. Records show that many black people were present at the court of James IV – servants yes but also invited guests and musicians. Much of what we know comes from the royal treasurers accounts which show that James’ purse paid wages and gifts to numerous ‘moors’. African drummers and choreographers were paid to perform, to have instruments repainted, or bought horses to accompany James on tour. The records also show black women present being gifted clothing, fabric and large sums of money. CATALINA & CATALINA AD 1501 In 1501 ‘la infant’ Catalina, daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, arrived in Plymouth to begin a new life in England. She came from one royal household and was travelling in preparation to be married into another, the fledgling Tudor dynasty. She was promised to Arthur, heir to the English throne. -

Durham Liber Vitae

-414- DURHAM LIBER VITAE Durham Liber Vitae: First page (as shown on the project website) with the name of King Athelstan, supposed donor of the liber to Durham, at the top. Reproduced by permission of British Library. Further copying prohibited. © British Library: Cotton Domitian A. VII f.15r DURHAM LIBER VITAE -415- THE DURHAM LIBER VITAE: SOME REFLECTIONS ON ITS SIGNIFICANCE AS A GENEALOGICAL RESOURCE by Rosie Bevan1 ABSTRACT The Durham Liber Vitae holds great potential for the extraction of unmined genealogical information held within its pages, but the quality of information obtained will depend on our understanding of the document itself. This article explores briefly what a liber vitae was and gives examples of the type of information that can be extracted from the Durham liber with special reference to Countess Ida, mother of William Longespee. Foundations (2005) 1 (6): 414-424 © Copyright FMG The Durham Liber Vitae (Book of Life), which contains over 11,000 medieval names on 83 folios, recorded over a period from the ninth to the sixteenth century, is receiving some well-deserved study2. The names in the Liber Vitae are of benefactors to St Cuthbert’s, Durham, and included kings and earls, as well as other landowning laity. Also appearing in large numbers are the names of those belonging to the religious community itself over that period. From the late 1000s Breton and Norman- French names feature, intermingling with those belonging to Anglo-Saxon, Scottish and Scandinavian families, witness to intermarriage between, and eventual cultural dominance over, racial groups and land in northern England. -

Form Foreign Policy Took- Somerset and His Aims: Powers Change? Sought to Continue War with Scotland, in Hope of a Marriage Between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots

Themes: How did relations with foreign Form foreign policy took- Somerset and his aims: powers change? Sought to continue war with Scotland, in hope of a marriage between Edward and Mary, Queen of Scots. Charles V up to 1551: The campaign against the Scots had been conducted by Somerset from 1544. Charles V unchallenged position in The ‘auld alliance’ between Franc and Scotland remained, and English fears would continue to be west since death of Francis I in dominated by the prospect of facing war on two fronts. 1547. Somerset defeated Scots at Battle of Pinkie in September 1547. Too expensive to garrison 25 border Charles won victory against forts (£200,000 a year) and failed to prevent French from relieving Edinburgh with 10,000 troops. Protestant princes of Germany at In July 1548, the French took Mary to France and married her to French heir. Battle of Muhlberg, 1547. 1549- England threatened with a French invasion. France declares war on England. August- French Ottomans turned attention to attacked Boulogne. attacking Persia. 1549- ratified the Anglo-Imperial alliance with Charles V, which was a show of friendship. Charles V from 1551-1555: October 1549- Somerset fell from power. In the west, Henry II captured Imperial towns of Metz, Toul and Verdun and attacked Charles in the Form foreign policy-Northumberland and his aims: Netherlands. 1550- negotiated a settlement with French. Treaty of In Central Europe, German princes Somerset and Boulogne. Ended war, Boulogne returned in exchange for had allied with Henry II and drove Northumberland 400,000 crowns. England pulled troops out of Scotland. -

Gilpin Family Rich.Ard De Gylpyn Joseph Gilpin The

THE GILPIN FAMILY FROM RICH.ARD DE GYLPYN IN 1206 IN A LINE TO JOSEPH GILPIN THE EMIGRANT TO AMERICA AND SOMETHING OF THE KENTUCKY GILPINS AND THEIR DESCENDANTS To 1916 Copyrighted in 1927 by Geor(Je Gilpin Perkins PRESS OF W, F- ROBERTS COMPANY WASHJNGTON, D, C. THE KENTUCKY GILPINS By GEORGE GILPIN PERKINS HIS genealogical study of the Gilpin families, covering the period of twenty generations prior to the Gil pin emigration to Kentucky, is gathered solely, so far as the simple line of descent goes, from an elaborate parchment pedi gree chart taken from the papers of Joshua Gilpin, Esquire, by his brother, Thomas Gilpin, Philadelphia, March, 1845, and in part, textu ally, from the work: by Dr. Joseph Elliott Gilpin, Baltimore, 1897, whose father and the Kentucky emigrants were brothers. His authority was a Genealogical Chart accompanying a manuscript published 1879 by the Cumberland and West moreland Antiquarian and Archreological Society of England entitled "Memoirs of Dr. Richard Gilpin of Scaleby Castle in Cumberland, written in the year 1791 by the Rev. William Gilpin, Vicar of Boldre, together with an account of the author by himself; and a pedigree of the Gilpin family." [ 5 ] T H E KENTUCKY GILPINS Richard de Gylpyn, the first of the name of whom there is authentic knowledge, was a scholar. He gave the family history a vigorous beginning, by becoming the Secretary and Adviser of the Baron of Kendal, who was unlearned, as were many in that day of superstition and igno rance, and accompanying him to Runnemede, where the Barons of England, after previous long parleys with the unscrupulous and tyrannical King John, forced him to grant to his oppressed people Magna Charta and, themselves, voluntarily lifted from their dependants many feudal op pressions. -

Dissertation Title Page

“Singing by Course” and the Politics of Worship in the Church of England, c1560–1640 By James Campbell Nelson Apgar A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor James Davies Professor Diego Pirillo Spring 2018 Abstract “Singing by Course” and the Politics of Worship in the Church of England, c1560–1640 by James Campbell Nelson Apgar Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair “Singing by course” was both a product of and a rhetorical tool within the religious discourses of post-Reformation England. Attached to a variety of ostensibly distinct practices, from choirs singing alternatim to congregations praying responsively, it was used to advance a variety of partisan agendas regarding performance and sound within the services of the English Church. This dissertation examines discourses of public worship that were conducted around and through “singing by course,” treating it as a linguistic and conceptual node within broader networks of contemporary religious debate. I thus attend less to the history of the vocal practices to which “by course” and similar descriptions were applied than to the polemical dynamics of these applications. Discussions of these terms and practices slipped both horizontally, to other matters of ritual practice, and vertically, to larger topics or frameworks such as the nature of the Christian Church, the production of piety, and the roles of sound and performance in corporate prayer. Through consideration of these issues, “singing by course” emerges as a rhetorical, political, and theological construction, one that circulated according to changing historical conditions and to the interests of various ecclesiastical constituencies. -

Clothing, Memory and Identity in 16Th Century Swedish Funerary Practice

Joseph M. Gonzalez 6 Fashioning Death: Clothing, Memory and Identity in 16th Century Swedish Funerary Practice Introduction King Gustav Vasa was married three times. In 1531, less than a decade after his election as King of Sweden, he made a match calculated to boost his prestige and help consolidate his position as king and married Katarina von Sax-Lauenburg, the daughter of Duke Magnus and a relative of the emperor. She bore the king one son, Erik, and died suddenly in 1535 (Svalenius, 1992). After her death, the king married the daughter of one of the most powerful noble houses in Sweden, Margareta Eriksdotter Leijonhufvud in 1536. Queen Margareta bore the king eight children before she died in 1551. By August of 1552, the fifty-six year old Gustav Vasa had found a new queen, the 16-year-old Katarina Gustavsdotter Stenbock, daughter of another of Sweden’s leading noble houses. Despite the youth of his bride, the marriage bore no children and the old king died eight years later (Svalenius, 1992). The king’s death occasioned a funeral of unprecedented magnificence that was unique both in its scale and in its promotion of the Vasa dynasty’s image and interests. Unique to Vasa’s funeral was the literal incorporation of the bodies of his two deceased wives in the ceremony. They shared his bed-like hearse on the long road to Uppsala and the single copper casket that was interred in the cathedral crypt. Six months after the funeral, Gustav Vasa’s son with Katarina von Sax-Lauenburg, Erik, was crowned king. -

Morris King Thompson, Jr

The Holy Eucharist with The Ordination and Consecration of Morris King Thompson, Jr. As a Bishop in the Church of God and Eleventh Bishop of Louisiana Saturday, May 8, 2010 10:00 AM Christ Church Cathedral New Orleans, Louisiana The People of God and Their Bishop In Christianity’s early centuries, bishops presided over urban churches, functioning as pastors to the Christians of their city and the surrounding countryside. Everyone came into the city on Sunday to participate in the urban liturgy as presided over by the local bishop. These bishops were also our chief theologians, reflecting on the faith in the context of their people’s lives and experiences. It was not until between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries that the parish priest became the usual person to preside over the Eucharistic assembly. The Greek word episcopacy (επισϰοπή) provides the origin of the word “episcopal.” In Greek, the word is related to the idea of visitation, specifically a divine revelation. It came to mean “overseer.” In English, the word means “of or relating to bishops.” In our scriptures, “overseer” was used somewhat interchangeably with the word “elder” (πϱϵσβυτέϱουϛ, presbyteros, from which comes the word priest), for one who leads the fledgling Christian community and holds to sound doctrine despite the danger presented by false teachers (see I Timothy 3:1-7, II Timothy 1:6-10, Titus 1:5-9 and I Peter 5:1-11). The images of a bishop in our Book of Common Prayer are derived from this history. As you will hear in this ordination liturgy, the bishop is understood to be our chief priest and presider of the diocese as well as its chief pastor. -

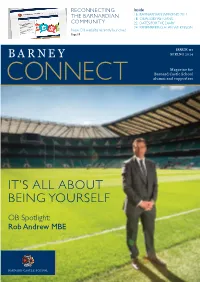

Barney Connect Issue 01 Alan Spring 2014 Stevens

RECONNECTING Inside THE BARNARDIAN 16 BARNARDIAN WEEKEND 2014 18 OB RUGBY RETURNS COMMUNITY 22 DATES FOR THE DIARY 24 REMEMBERING ALAN WILKINSON New OB website recently launched Page 19 ISSUE 01 BARNEY SPRING 2014 Magazine for Barnard Castle School CONNECT alumni and supporters IT’S ALL ABOUT BEING YOURSELF OB Spotlight: Rob Andrew MBE 2 ISSUE 01 Contact Welcome BARNEY CONNECT ISSUE 01 ALAN SPRING 2014 STEVENS Headmaster Barnard School Castle Alumni & Archive Recently I received a letter from Bruce Crawcour, an Old Barnardian Miss Dorothy Jones: in Shrewsbury, formerly of Durham House from 1958-1964. +44 (0)1833 696025 Enclosed with the letter was an aged and yellowing piece of paper [email protected] which dated from 1886. It was an original programme for the opening of the main school building which brought the School back to Barney from Published in partnership with Middleton-one-Row and situated it close to the decrepit medieval the Old Barnardians’ Club institution which gave it part of its foundation. On the cover of the programme, the School’s architect, Robert Johnson, had drawn a sketch of the front of the new building, but – with typical architect’s license – he had gone even further and had drawn something which did not even exist then. Just to the east of School House (what is now Brereton House and the Linen Room) he had drawn a Chapel. What he drew, however, was quite different in both style and orientation from what we have today. He drew a chapel in sympathy with All correspondence to be directed the design of the main building which appeared to have a belfry in the style through the OB Club Secretary of a pepperpot on its roof. -

Forgery and Miracles in the Reign of Henry Viii*

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): Peter Marshall Article Title: Forgery and Miracles in the Reign of Henry VIII Year of publication: 2003 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/past/178.1.39 Publisher statement: This is a pre-copy-editing, author-produced PDF of an article accepted for publication in Past and Present following peer review. The definitive publisher-authenticated version Marshall, P. (2003). Forgery and Miracles in the Reign of Henry VIII. Past and Present,Vol. 178, pp. 39-73 is available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/past/178.1.39 FORGERY AND MIRACLES IN THE REIGN OF HENRY VIII* Peter Marshall, University of Warwick In June 1534, as the final ties connecting the English Church to Rome were inexorably being severed, Archbishop Thomas Cranmer issued an order for the preservation of ‘unity and quietness’. For the space of a year, preachers were to steer clear of six topics which ‘have caused dissension amongst the subjects of this realm’, namely, ‘purgatory, honouring of saints, that priests may have wives, that faith only justifieth, to go on pilgrimages, to forge miracles’.1 The first four items on this list represent important doctrinal flash-points of the early Reformation; the fifth, an increasingly contentious ingredient of popular religious culture. -

Cabinet 6 February 2019 School Admission Arrangements Academic

Cabinet 6 February 2019 School Admission Arrangements Academic Year 2020/21 Report of Corporate Management Team Margaret Whellans, Corporate Director, Children and Young People's Services Councillor Olwyn Gunn, Portfolio Holder for Children and Young People’s Services Electoral division(s) affected: Countywide Purpose of the Report 1 The purpose of this report is to ask Cabinet to consider and approve the proposed admission arrangements and oversubscription criteria for Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools for the 2020/21 academic year. Executive summary 2 There is a proposed additional criterion to the current oversubscription criteria for admission to Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools. The Government wishes admission authorities to introduce oversubscription criteria to give children who were previously in state care outside of England, and have ceased to be in state care as a result of being adopted, second highest priority for admission into school. This is because the Government believes such children are vulnerable and may have experienced abuse and neglect prior to being adopted. 3 Consultation has been carried out with schools, other admission authorities, Governing Bodies and parents on the council's admission arrangements in accordance with the national School Admissions Code as it is 7 years since they were last consulted on. Recommendation 4 Cabinet is asked to agree the proposed oversubscription criteria for admission to Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools; and to agree the following in respect of Community and Voluntary Controlled Schools, when determining the admission arrangements for 2020/21: (i) That the proposed admission numbers as recommended in Appendix 2 be approved. (ii) That the admission arrangements at Appendix 3 be approved.