Soft Money Spending by State Parties: Where Does It Really Go?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Leadership—Perspectives and Practices

Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Public Leadership Perspectives and Practices Edited by Paul ‘t Hart and John Uhr Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/public_leadership _citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Public leadership pespectives and practices [electronic resource] / editors, Paul ‘t Hart, John Uhr. ISBN: 9781921536304 (pbk.) 9781921536311 (pdf) Series: ANZSOG series Subjects: Leadership Political leadership Civic leaders. Community leadership Other Authors/Contributors: Hart, Paul ‘t. Uhr, John, 1951- Dewey Number: 303.34 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by John Butcher Images comprising the cover graphic used by permission of: Victorian Department of Planning and Community Development Australian Associated Press Australian Broadcasting Corporation Scoop Media Group (www.scoop.co.nz) Cover graphic based on M. C. Escher’s Hand with Reflecting Sphere, 1935 (Lithograph). Printed by University Printing Services, ANU Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2008 ANU E Press John Wanna, Series Editor Professor John Wanna is the Sir John Bunting Chair of Public Administration at the Research School of Social Sciences at The Australian National University. He is the director of research for the Australian and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG). -

2019 Contribution Refund Summary for Political Party Units Democratic

2019 Contribution Refund Summary for Political Party Units Note: Contributions from a married couple filing jointly are reported as one contribution Party Units Contribution Number Refund Democratic Farmer Labor Party 1st Senate District DFL 5 $450.00 2nd Congressional District DFL 16 $696.28 3rd Congressional District DFL 6 $435.00 5B House District DFL 7 $360.00 5th Congressional District DFL 1 $50.00 5th Senate District DFL 1 $40.00 6th Congressional District DFL 9 $621.42 6th Senate District DFL 2 $150.00 8th Congressional District DFL 1 $100.00 8th Senate District DFL 4 $250.00 9th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 10th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 11A House District DFL 1 $50.00 11th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 12th Senate District DFL 2 $200.00 13th Senate District DFL 17 $1,266.67 14th Senate District DFL 9 $620.00 16th Senate District DFL 36 $2,534.98 19th Senate District DFL 2 $100.00 20th Senate District DFL 7 $350.00 22nd Senate District DFL 3 $200.00 Party Units Contribution Number Refund 25B House District DFL (Olmsted-25) 64 $4,092.75 25th Senate District DFL 4 $200.00 26th Senate District DFL 1 $100.00 29th Senate District DFL 25 $1,920.00 30th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 31st Senate District DFL 4 $300.00 32nd Senate District DFL 27 $1,900.00 33rd Senate District DFL 43 $3,070.00 34th Senate District DFL 74 $5,310.00 35th Senate District DFL 17 $1,301.30 36th Senate District DFL 2 $150.00 37th Senate District DFL 1 $100.00 38th Senate District DFL 11 $730.00 39th Senate District DFL 14 $1,185.00 40th Senate District DFL -

Building Political Parties

Building political parties: Reforming legal regulations and internal rules Pippa Norris Harvard University Report commissioned by International IDEA 2004 1 Contents 1. Executive summary........................................................................................................................... 3 2. The role and function of parties....................................................................................................... 3 3. Principles guiding the legal regulation of parties ........................................................................... 5 3.1. The legal regulation of nomination, campaigning, and elections .................................................................. 6 3.2 The nomination stage: party registration and ballot access ......................................................................... 8 3.3 The campaign stage: funding and media access...................................................................................... 12 3.4 The electoral system: electoral rules and party competition....................................................................... 13 3.5: Conclusions: the challenges of the legal framework ................................................................................ 17 4. Strengthening the internal life of political parties......................................................................... 20 4.1 Promoting internal democracy within political parties ............................................................................. 20 4.2 Building -

Grassroots Party Activity in the South

Grassroots Party Activity in the South Charles Prysby Department of Political Science University of North Carolina at Greensboro John A. Clark Department of Political Science Western Michigan University Prepared for presentation at the conference on “The State of the Parties: 2004 and Beyond,” organized by the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics, University of Akron, and held on October 5-7, 2005. This study relies on data collected by the Southern Grassroots Party Activists 2001 project, which was supported by National Science Foundation grants SES-9986501 and SES-9986523. The findings and conclusions of this study are those of the authors and do not represent the opinions of the National Science Foundation or any other government agency. Grassroots Party Activity in the South For months leading up to the 2004 elections, supporters of the Democratic party registered new voters, organized door-to-door, telephone, and e-mail canvasses, and prepared to mobilize an army of voters on behalf of presidential nominee John Kerry and other candidates. Their efforts were coordinated with campaigns of various party candidates, party organizations at the national, state, and local levels, and party-affiliated groups such as labor unions and MoveOn.org. Their hard work paid off on election day: Kerry received 8 million more votes than Al Gore received in winning the popular vote in 2000. There was only one problem with the Democrats’ plan. While turnout in support of Democratic candidates in 2004 exceeded previous levels, it paled in comparison to the success enjoyed by Republicans. Republican candidates, party organizations, and affiliated groups were able to increase votes on behalf of George W. -

Testimony of Chris Wright, Grassroots Party, Submitted to the Committee on Commerce, Finance and Policy Minnesota House of Representatives February 17, 2021

Testimony of Chris Wright, Grassroots Party, Submitted to the Committee on Commerce, Finance and Policy Minnesota House of Representatives February 17, 2021 Chairman Stephenson, members of the Commerce, Finance and Policy Committee, thank you for considering my testimony on HF600. When it comes to defending our fragile democracy, restoring citizen control of government and reigning in corporate power we are in the fight of our lives. I want to thank House Majority Leader, Ryan Winkler, for his extensive work on this bill. The town hall forums Rep. Winkler named “Be heard on Cannabis,” were well attended. I attended all but one. Throughout the state, when called upon, I turned and asked locals, ”All in favor of growing as much cannabis as you want in your backyard garden without a license as guaranteed in the Minnesota Constitution? raise your hand,” virtually all hands were raised in favor. When asked, “Those opposed, raise your hand,” perhaps a few hands were raised in opposition. Will you ask your constituents the same question? Will they be “Heard on Cannabis?” I fundamentally disagree with Representative Winkler’s denial of our Constitutional rights in this bill, however, I agree with the vast majority of what is contained in it. Up to now, there have been futile efforts to craft a bill to legalize adult-use cannabis. Unfortunately, little time and legislative labor has been used in a detailed examination of the historic “criminalization by fraud” of cannabis. It says in Article 13, Section 7 [A13,S7], of the Minnesota Constitution, “No license required to peddle. Any person may sell or peddle the products of the farm or garden occupied and cultivated by him without obtaining a license therefor.” In 1935, the same year Minnesota legalized liquor, Governor Floyd Olson and the legislature criminalized cannabis by requiring a pharmacy license. -

Village Economic Autonomy and Authoritarian Control Over Village Elections in China

The London School of Economics and Political Science Village economic autonomy and authoritarian control over village elections in China - Evidence from rural Guangdong Province Ting Luo A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, March 2014 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 86,348 words. I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Joanna Cummings of Transformat. Ting Luo 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the effects of village economic wealth and economic autonomy on the authoritarian control of local government over village elections in China. With new data - qualitative evidence and quantitative data collected from the extensive fieldtrips to a county in Guangdong Province, this study finds that given that village elections operate within China’s one party authoritarian regime and the official purpose of the elections is to solve the grassroots governance crisis, local government have the incentive to control the elections in their favour, that is, to have incumbents and/or party members elected. -

Everyday Party Politics: Local Volunteers and Professional Organizers in Grassroots Campaigns

Everyday Party Politics: Local volunteers and professional organizers in grassroots campaigns Elizabeth H Super PhD in Politics The University of Edinburgh 2009 1 Everyday Party Politics: Local volunteers and professional organizers in grassroots campaigns Table of Contents Declaration .................................................................................................................3 Abstract ......................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................5 Preface .......................................................................................................................6 Chapter 1: Introduction ...............................................................................................8 Chapter 2: Research Design ....................................................................................32 Chapter 3: Organization ...........................................................................................65 Chapter 4: Learning..................................................................................................90 Chapter 5: Motives and Meaning............................................................................121 Chapter 6: Representation and Linkage.................................................................155 Chapter 7: Professional organizers and expert volunteers.....................................180 -

Maintaining Party Unity: Analyzing the Conservative Party of Canada's

Maintaining Party Unity: Analyzing the Conservative Party of Canada’s Integration of the Progressive Conservative and Canadian Alliance parties by Matthew Thompson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2017, Matthew Thompson Federal conservative parties in Canada have long been plagued by several persistent cleavages and internal conflict. This conflict has hindered the party electorally and contributed to a splintering of right-wing votes between competing right-wing parties in the 1990s. The Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) formed from a merger of the Progressive Conservative (PC) party and the Canadian Alliance in 2003. This analysis explores how the new party was able to maintain unity and prevent the long-standing cleavages from disrupting the party. The comparative literature on party factions is utilized to guide the analysis as the new party contained faction like elements. Policy issues and personnel/patronage distribution are stressed as significant considerations by the comparative literature as well literature on the PCs internal fighting. The analysis thus focuses on how the CPC approached these areas to understand how the party maintained unity. For policy, the campaign platforms, Question Period performance and government sponsored bills of the CPC are examined followed by an analysis of their first four policy conventions. With regards to personnel and patronage, Governor in Council and Senate appointments are analyzed, followed by the new party’s candidate nomination process and Stephen Harper’s appointments to cabinet. The findings reveal a careful and concentrated effort by party leadership, particularly Harper, at managing both areas to ensure that members from each of the predecessor parties were motivated to remain in the new party. -

2018 Contribution Refund Summary for Political Party Units

2018 Contribution Refund Summary for Political Party Units Note: Contributions from a married couple filing jointly are reported as one contribution Party Units Contribution Number Refund Democratic Farmer Labor Party 2nd Congressional District DFL 8 $500.00 3rd Congressional District DFL 23 $1,400.00 5B House District DFL 5 $275.00 7th Senate District DFL 4 $244.00 8th Senate District DFL 2 $100.00 11A House District DFL 7 $500.00 12th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 13th Senate District DFL 29 $2,145.00 14th Senate District DFL 15 $1,017.14 15B House District DFL 1 $57.14 15th Senate District DFL 3 $250.00 16th Senate District DFL 5 $450.00 17th Senate District DFL 3 $150.00 18th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 19th Senate District DFL 2 $150.00 20th Senate District DFL 3 $150.00 22nd Senate District DFL 2 $150.00 24th Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 25B House District DFL (Olmsted-25) 19 $1,012.69 29th Senate District DFL 2 $150.00 31st Senate District DFL 4 $247.14 Party Units Contribution Number Refund 32nd Senate District DFL 35 $2,320.00 33rd Senate District DFL 24 $1,340.53 34th Senate District DFL 49 $3,415.00 35th Senate District DFL 7 $550.00 36th Senate District DFL 10 $474.99 37th Senate District DFL 4 $165.00 39th Senate District DFL 9 $602.32 40th Senate District DFL 2 $67.85 41st Senate District DFL 7 $396.42 43rd Senate District DFL 1 $50.00 44th Senate District DFL 94 $6,663.42 45th Senate District DFL 3 $85.00 46th Senate District DFL 47 $2,704.24 48th Senate District DFL 49 $2,892.37 49th Senate District DFL 59 $3,894.10 50th -

Testimony of Chris Wright, Grassroots Party, Submitted to the Judiciary, Finance & Civil Law Minnesota House of Representatives Wednesday, April 14, 2021

Testimony of Chris Wright, Grassroots Party, Submitted to the Judiciary, Finance & Civil Law Minnesota House of Representatives Wednesday, April 14, 2021 Madam Chair and Committee Members, the only reason why I urge you to support HF600 is because we get more justice from the Legalization by Fraud than Criminalization by Fraud, but fraud is fraud. Article 13, Section 7, of the Minnesota Constitution, says, “Any person may sell or peddle the products of the farm or garden occupied and cultivated by him without obtaining a license therefore.” Indeed, Section 8, of this bill is illegal and unconstitutional. While artificial entities may be licensed, natural persons cannot. To jail farmers, Governor Floyd Olson, and the Legislature of 1935, defrauded Minnesotans of this right by requiring an illegal pharmacy license. This historic injustice usurped and defrauded us of our freedom to cultivate without a license. They destroyed public safety; solicited & monetized crime; caused murder, false imprisonment, systemic racism, trigger-happy police and then they had the nerve to call us ‘criminals?’ And now you want us to reward this criminal act by giving you police power to defraud us again? And we’re just supposed to let you get away with it? Cannabis makes you cough, but politics makes you gag! Please, those with integrity, restore our rights, reform our laws and, with any luck, reveal to a doubting world what Minnesota still can be? Thank you Please consider these extended remarks: Article 1, Section 2, Cannabis Management Board? Why are we duplicating effort when we could save the taxpayers more money if it were placed this inside the Department of Public Safety’s – Alcohol and Gambling Enforcement Division? Section 2, 7d, opens the revolving door by allowing members of the Cannabis Advisory Board to take lobbying jobs after only two years. -

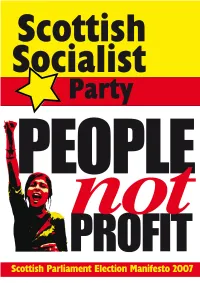

Manifesto Part One About the Scottish Socialist Party “Work As If You Live in the Early Days of a Better Nation” Alasdair Gray

manifesto part one About the Scottish Socialist Party “Work as if you live in the early days of a better nation” Alasdair Gray e are the Scottish Socialists of life’, across the world people are and we fight in hope. We cut already dying as a result of climate against the grain of the politi- change caused by that same way of life. W cal consensus, refusing to We have only a very short time left to accept that ‘in the real world’, millions stop the Earth from burning because of must live in poverty for a few to live in the destructive waste of capitalism. unimaginable wealth, that weapons of Since the last Scottish Parliamentary mass destruction must be moored in the election in 2003, a brutal war has been Clyde to keep us safe from weapons of raging in Iraq, courtesy of the British mass destruction, that wars mean peace, and American governments. and that a diminishing democracy deliv- Hundreds of thousands of civilians ers us greater security. have lost their lives, and their society has We believe we can make a better been pounded to dust. nation, where every state school child FIGHTING FOR A eats a nutritious, free lunch every day of FUTURE: for a the working week; where pensioners world without receive a decent income with access to poverty, war and well-funded, free public services; where environmental families are housed in warm, secure destruction, for a homes near green spaces and schools world of peace, equality and justice and shops; where refugees are welcomed and given the right to work and make a new life here, to the benefit of us all; PHOTO: where war is an ugly memory; where Craig Maclean energy is sustainable and nationalised; BACK PAGE where we protect instead of destroy our PHOTO: Eddie Truman environment; and where expanded, fare- free and publicly-owned train, bus and ferry services link every community in Scotland, from the heart of Glasgow to the shores of the Outer Hebrides. -

Thursday January 18 Agenda

MEETING OF THE CANNABIS COMMISSION City Hall Thursday, January 18, 2018 2180 Milvia Street 2:00 PM Redwood Room (Sixth Floor) AGENDA I. Call to Order A. Roll Call and Ex Parte Communication Disclosures B. Changes to Order of Agenda II. Public Comment III. Approval of Minutes A. November 16, 2017 Draft Action Minutes IV. Planning Staff Report V. Chairperson’s Report VI. Subcommittee Report VII. Discussion and Action Items A. Election of chairperson B. Review staff proposed changes to cannabis ordinance language and vote on Commission recommendation to Council. Attachments: 1. Staff report a. 7-25-17 Council referral b. Matrix of existing and proposed ordinances/regulations c. Draft new BMC chapter 12.21 (General Regulations) d. Draft new BMC Chapter 12.22 (Operating Standards) e. Draft new BMC Chapter 20.XX (Cannabis Advertising) f. Existing BMC Chapters 12.23, 12.25 and 12.27 showing new locations for existing ordinance language g. Draft changes to Zoning Ordinance: new Chapter 23C.25 (Cannabis Businesses), modified use tables in C- and M-Districts and new Definition (23F.040) h. Existing Zoning Ordinance Sections 23E.16.070, 23E.72.040 showing new locations for existing ordinance language C. Review staff report regarding location selection process for Apothecarium and vote on Commission representative for January 23, 2018 Council meeting. (NOTE: Staff report and resolution to be distributed at the meeting. Both will be available on the Council’s website by 1-12-18: https://www.cityofberkeley.info/Clerk/City_Council/City_Council__Agenda_Index.aspx) VIII. Information Items (In compliance with the Brown Act, no action may be taken on these 1 of 113 items; however, they may be discussed and placed on a subsequent agenda for action): A.