Kings, Lords & Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1592213370-Monetize.Pdf

Table of Contents 1. Online Monetization: How to Turn Your Following into Cash 1.1 What is monetization? 1.2 How to monetize your website, blog, or social media channel 1.3 Does a monetization formula exist? Chapter 1 Takeaways 2. How to Monetize Your Blog The Right Way 2.1 Why should you start monetizing with your blog? 2.2 How to earn money from blogging 2.3 How to transform your blog visitors into loyal fans 2.4 Blog monetization tools you should know about Chapter 2 Takeaways 3. Facebook Monetization: The What, Why, Where, and How 3.1 How Facebook monetization works 3.2 Facebook monetization strategies Chapter 3 Takeaways 4. How to monetize your Instagram following 4.1 Before you go chasing that Instagram money... 4.2 The four main ways you can earn money on Instagram 4.3 Instagram monetization tools 4.4 Ideas to make money on Instagram Chapter 4 Takeaways 5. Monetizing a YouTube Brand Without Ads 5.1 How to monetize Youtube videos without Adsense 5.2 Essential Youtube monetization tools 5.3 Factors that determine your channel’s long-term success Chapter 5 Takeaways 1. Online Monetization: How to Turn Your Following into Cash 5 Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Jenn, a customer service agent at a car leasing company, is fed up with her job. Her pay’s lousy, she’s on edge with customers yelling at her over the phone all day (they actually treat her worse in person), and her boss ignores all her suggestions, even though she knows he could make her job a lot less stressful. -

The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos)

7/5/2017 The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos) The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos) JUNE 20, 2017 BY JASON DEBORD Fans of The Moody Blues got to experience the band like never before on Sunday night at Ironstone Amphitheatre.c Featuring “an evening with…” style concert presentation, The Moody Blues played two full sets in front of the massive crowd in attendance, the Úrst with various hits from their career and the second presenting a track by track playing of every songs from their groundbreaking album, Days of Future Passed, which celebrates it’s 50th anniversary this year.c They looked and sounded great, and there was a lot of magic in the air as they recreated this landmark album live on stage. http://rocksubculture.com/2017/06/20/the-moody-blues-at-ironstone-amphitheatre-murphys-california-6182017-concert-review-photos/ 1/10 7/5/2017 The Moody Blues at Ironstone Amphitheatre | Murphys, California | 6/18/2017 (Concert Review + Photos) What: Days of Future Passed 50th Anniversary Tour Who: The Moody Blues Venue: Ironstone Amphitheatre at Ironstone Vineyards Where: Murphys, California Promoter: Richter Entertainment Group When: June 18, 2017 Seating: (house photographer) Richter Entertainment Group’s Summer Concert Season at Ironstone Amphitheatre in Murphys in 2017 features Toby Keith, Boston, Joan Jett & The Blackhearts, John Mellencamp, The Moody Blues, Jason Mraz, Lindsey Buckingham and Christine McVie, matchbox twenty, Counting Crows, Steve Miller Band, Peter Frampton, Willie Nelson, Kenny G, George Benson, and more!c It’s all taking place in June, July, August and September this year. -

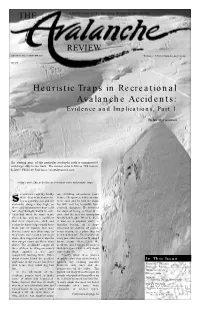

Heuristic Traps in Recreational Avalanche Accidents: Evidence and Implications, Part 1

TH E A Publication of the American Avalanche Association RE V I E W VOLUME 22, NO. 2 • DECEMBER 2003 Website: www.a v a l a n c h e . o rg / ~ a a a p US $4.95 Heuristic Traps in Recreational Avalanche Accidents: Evidence and Implications, Part 1 By Ian McCammon The starting zone of this particular avalanche path is unsupported with large cliffs in the track. The runout zone is 500 to 750 meters below." Photo by Paul Laca / snowdynamics.com editor’s note: This is the first in a two-part series on heuristic traps. everal years ago my buddy our climbing adventures years Steve died in an avalanche. before. Things were different now, S It was a stormy day and the Steve said, and he told me about avalanche danger was high, so his wife and his beautiful four- Steve and his partners chose a ski y e a r-old daughter. He believed tour they thought would be safe. his days of being reckless were They had skied the route many over, and the time for raising his times before and were confident family had begun. When he died, that their experience, skill and it was on a popular route in avalanche knowledge would keep familiar terrain, on a slope them out of trouble that day. traversed by dozens of people Several hours into their tour, as every season, in a place that he they broke trail across a low-angle believed was safe. The foolish risk slope, they triggered an avalanche story just didn’t seem to fit what I that swept down on them from knew about Steve and the above. -

Justin Hayward All the Way, and More Tour

Presented in Cooperation with DANNY ZELISKO PRESENTS Justin Hayward All The Way, And More Tour Tuesday, August 27, 2019; 7:30 pm ABOUT There Somewhere,’ and ‘Your Wildest Dreams.’ These laid the foundation for the incredible success story of the Moody Having chalked up nearly fifty years at the peak of the music Blues — as well as his solo work — which continues to this day. and entertainment industry, Justin Hayward’s voice has When the Moody Blues took a break from touring in 1975, been heard the world over. Known principally as the vocalist, Justin worked on the Blue Jays album, followed by the hit lead guitarist and composer for the Moody Blues, his is an single ‘Blue Guitar’ (recorded with the members of 10cc). enduring talent that has helped to define the times in which Although the Moodies continued to record and tour at the he has worked. Over the last forty-five years, the band has highest level, Justin also found time to create several solo sold fifty-five million albums and received numerous awards. albums: Songwriter, Night Flight, Moving Mountains and The Commercial success has gone hand in hand with critical View From the Hill. acclaim, The Moody Blues are renowned the world over as innovators and trail blazers who have influenced any number Proving that he could write massive hits outside of the Moody of fellow artists. The band was inducted in to the Rock and Blues, Justin hit the Top Ten globally in 1978 with 'Forever Roll Hall of Fame class of 2018. Autumn’ — created for Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds album. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - Updated April 9, 2006

The Moody Blues Tour / Set List Project - updated April 9, 2006 compiled by Linda Bangert Please send any additions or corrections to Linda Bangert ([email protected]) and notice of any broken links to Neil Ottenstein ([email protected]). This listing of tour dates, set lists, opening acts, additional musicians was derived from many sources, as noted on each file. Of particular help were "Higher and Higher" magazine and their website at www.moodies- magazine.com and the Moody Blues Official Fan Club (OFC) Newsletters. For a complete listing of people who contributed, click here. Particular thanks go to Neil Ottenstein, who hosts these pages, and to Bob Hardy, who helped me get these pages converted to html. One-off live performances, either of the band as a whole or of individual members, are not included in this listing, but generally can be found in the Moody Blues FAQ in Section 8.7 - What guest appearances have the band members made on albums, television, concerts, music videos or print media? under the sub-headings of "Visual Appearances" or "Charity Appearances". The current version of the FAQ can be found at www.toadmail.com/~notten/FAQ-TOC.htm I've construed "additional musicians" to be those who played on stage in addition to the members of the Moody Blues. Although Patrick Moraz was legally determined to be a contract player, and not a member of the Moody Blues, I have omitted him from the listing of additional musicians for brevity. Moraz toured with the Moody Blues from 1978 through 1990. From 1965-1966 The Moody Blues were Denny Laine, Clint Warwick, Mike Pinder, Ray Thomas and Graeme Edge, although Warwick left the band sometime in 1966 and was briefly replaced with Rod Clarke. -

Pianodisc Music Catalog.Pdf

Welcome Welcome to the latest edition of PianoDisc's Music Catalog. Inside you’ll find thousands of songs in every genre of music. Not only is PianoDisc the leading manufacturer of piano player sys- tems, but our collection of music software is unrivaled in the indus- try. The highlight of our library is the Artist Series, an outstanding collection of music performed by the some of the world's finest pianists. You’ll find recordings by Peter Nero, Floyd Cramer, Steve Allen and dozens of Grammy and Emmy winners, Billboard Top Ten artists and the winners of major international piano competi- tions. Since we're constantly adding new music to our library, the most up-to-date listing of available music is on our website, on the Emusic pages, at www.PianoDisc.com. There you can see each indi- vidual disc with complete song listings and artist biographies (when applicable) and also purchase discs online. You can also order by calling 800-566-DISC. For those who are new to PianoDisc, below is a brief explana- tion of the terms you will find in the catalog: PD/CD/OP: There are three PianoDisc software formats: PD represents the 3.5" floppy disk format; CD represents PianoDisc's specially-formatted CDs; OP represents data disks for the Opus system only. MusiConnect: A Windows software utility that allows Opus7 downloadable music to be burned to CD via iTunes. Acoustic: These are piano-only recordings. Live/Orchestrated: These CD recordings feature live accom- paniment by everything from vocals or a single instrument to a full-symphony orchestra. -

The Perry 200 Commemoration Concludes with Tall Ships Erie 2013, Marking the Celebration of Erie's Proud FOLLOWING up on the WEIGHT of WAR Past and Bright Future

Erie’s only free, independent source for news, culture, and entertainment Sept 4 - 17 / Vol. 3, No. 18 / ErieReader.com E I R RE EADER The Perry 200 Commemoration Concludes with Tall Ships Erie 2013, Marking the Celebration of Erie's Proud FOLLOWING UP ON THE WEIGHT OF WAR Past and Bright Future THE REPUBLICAN GAME OVER SYRIA THE MARCH ON WASHINGTON 50 YEARS LATER NO FRACKING WAY ERIE CHAMBER ORCHESTRA KICKS OFF NEW SEASON PREVIEWS OF THE ERIE PLAYHOUSE AND MIAC UPCOMING SEASONS ARTS ‘N DRAFTS MUSIC, FASHION, TECH FREE 2 | Erie Reader | eriereader.com September 4, 2013 CONTENT September9 4, 2013 FEATURE CULTURE 9 tall ships 12 COMMUnitY editors-in-chief: No Fracking Way Brian Graham & Adam Welsh anchor in erie Managing editor: The Perry 200 Commemoration Ben Speggen 14 iF We Were YoU... Concludes with Tall Ships Erie 2013 contributing editors: Here’s what we would do Cory Vaillancourt Jay Stevens NEWS AND NOTES 15 TO-Do list copy editor: Alex Bieler 4 UpFRONT Erie Chamber Orchestra Opening contributors: Deny, Deride, Dismiss Night Celebration, Arts 'N Drafts Alex Bieler Pen Ealain 5 street CORNER SOAPBoX 16 alBUM reVieWs Matthew Flowers The Impending War in Syria Dakota Hoffman 17 street FASHIONISTA Leslie McAllister 6 the WaY i see it Garrett Skindell Rich McCarty The March on Washington 50 Years Later Ryan Smith Jay Stevens 6 tech WATCH 18 season preVeiWs Rebecca Styn Mercyhurst Institute for Arts and Google Chromecast Bryan Toy Culture, The Erie Playhouse Designers: Mark Kosobucki Burim Loshaj photographer: Ryan Smith Brad Triana of Lake Erie, which propelled The years from now celebrate? Jessica Yochim Flagship City to the forefront of We then must ask ourselves: interns: From the Editors the nation’s mind and to the fore- What will we have done in the next Adam Kelly front of the future of America. -

The Dictionary Legend

THE DICTIONARY The following list is a compilation of words and phrases that have been taken from a variety of sources that are utilized in the research and following of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups. The information that is contained here is the most accurate and current that is presently available. If you are a recipient of this book, you are asked to review it and comment on its usefulness. If you have something that you feel should be included, please submit it so it may be added to future updates. Please note: the information here is to be used as an aid in the interpretation of Street Gangs and Security Threat Groups communication. Words and meanings change constantly. Compiled by the Woodman State Jail, Security Threat Group Office, and from information obtained from, but not limited to, the following: a) Texas Attorney General conference, October 1999 and 2003 b) Texas Department of Criminal Justice - Security Threat Group Officers c) California Department of Corrections d) Sacramento Intelligence Unit LEGEND: BOLD TYPE: Term or Phrase being used (Parenthesis): Used to show the possible origin of the term Meaning: Possible interpretation of the term PLEASE USE EXTREME CARE AND CAUTION IN THE DISPLAY AND USE OF THIS BOOK. DO NOT LEAVE IT WHERE IT CAN BE LOCATED, ACCESSED OR UTILIZED BY ANY UNAUTHORIZED PERSON. Revised: 25 August 2004 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A: Pages 3-9 O: Pages 100-104 B: Pages 10-22 P: Pages 104-114 C: Pages 22-40 Q: Pages 114-115 D: Pages 40-46 R: Pages 115-122 E: Pages 46-51 S: Pages 122-136 F: Pages 51-58 T: Pages 136-146 G: Pages 58-64 U: Pages 146-148 H: Pages 64-70 V: Pages 148-150 I: Pages 70-73 W: Pages 150-155 J: Pages 73-76 X: Page 155 K: Pages 76-80 Y: Pages 155-156 L: Pages 80-87 Z: Page 157 M: Pages 87-96 #s: Pages 157-168 N: Pages 96-100 COMMENTS: When this “Dictionary” was first started, it was done primarily as an aid for the Security Threat Group Officers in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). -

A Brief History of Analog Synthesis Ondioline

Product Information Document Synthesizers and Samplers K-2 Analog and Semi-Modular Synthesizer with Dual VCOs, Ring Modulator, External Signal Processor, 16-Voice Poly Chain and Eurorack Format ## Amazing analog synthesizer with dual VCO design allows for insanely fat music creation ## Authentic reproduction of original circuitry with matched transistors A Brief History of and JFETs Analog Synthesis ## Pure analog signal path based on The modern synthesizer’s evolution authentic VCO, VCF and VCA designs began in 1919, when a Russian physicist ## Semi-modular architecture named Lev Termen (also known as with default routings requires no patching for immediate Léon Theremin) invented one of the performance first electronic musical instruments – ## First and second generation filter the Theremin. It was a simple oscillator design (high pass/low pass with peak/resonance) that was played by moving the performer’s hand in the vicinity of the ## 4 variable oscillator shapes with variable pulse widths and ring instrument’s antenna. An outstanding modulation for ultimate sounds example of the Theremin’s use can be ## Dedicated and fully analog heard on the Beach Boys iconic smash triangle/square wave LFO hit “Good Vibrations”. ## 2 analog Envelope Generators for modulation of VCF and VCA ## 16-voice Poly Chain allows Ondioline combining multiple synthesizers for In the late 1930s, French musician up to 16 voice polyphony Georges Jenny invented what he called ## Complete Eurorack solution – the Ondioline, a monophonic electronic main module can be transferred keyboard capable of generating a wide range to a standard Eurorack case of sounds. The keyboard even allowed the player to produce natural-sounding vibrato by ## 36 controls give you direct and real-time access to all important depressing a key and using side-to-side finger parameters movements. -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

4\ the Friday Morning M Arterback Album Report

I<AL RUI)IVIAN PUB USHER ,1111:-uur 19th ye:Z._ ofService FRED DEANE 13`.°,acicasr/ M to th e -«*- OCT. 10, 1986 Ind ustries usIc EDITOR 44\ THE FRIDAY MORNING MARTERBACK® ALBUM REPORT XF_Cli I I\L MEW'S • 931 E A<-0 ION HIKE I 9 • III RH HI I NI 11 II k`-)F ()8003 • (609) 424 9114 Deane's List THE xe .LI thIl: ElPileTw eEeat? eeP ea BLI-111Yulj Dtt'w i''reoWsil e k Sia LK órs Cár Rsi * yer '6us and Fleetwood Mac the '70s, the Police a-e the seatbelts! For those of you who were asking, defnitive '80s band -- the decade's most successful "Where's the guitar", well fret not 'cause here it group, and arguably its most influential and innova- comes. "Whiplash" smokes from start to finish. tive. "Don't Stand So Close To Me '86" is thair Billy's snarling signature vocal style along with haunting and sentimental swansong, with the Godley & Steve Stevens' searing, scorching axe work puts Creme video providing the appropriate career retro- them at the top of their game. "Lover" surges 9-6 spective. The lyrics take on a candidly frank new and continues to impress monumentally -- #1 in meaning and the orchestral layerings make for one of play-ups with 38 and the phones are steamin', #3 their most. stunning arrangements to date. Most Requested. Be prepared to deal with "Worlds I usAl-t-c— \2,tr c-P.,L73\i li I t,....b..b\5 1 Forgotten Boy", "Don't Need A Gun", "Soul Standing By" and the tender "Sweet Sixteen".