INTERVIEWEE BIOS: Natalie White, Kamala Lopez, and Wendy J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

47Th TFF Lineup.Docx

August 3, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 47TH TELLURIDE FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES FILM LINEUP FOR ITS CANCELLED 2020 EVENT TELLURIDE, CO – Telluride Film Festival, presented by the National Film Preserve, released today its official program selections for the now-cancelled event. The Festival, whose ethos is to bring together film enthusiasts, filmmakers and artists to celebrate cinematic excellence, was scheduled to take place over Labor Day weekend, September 3-7, 2020. The Festival previously announced its cancellation due to the COVID-19 global pandemic. Representing twenty-five countries, the Festival’s program includes twenty-nine new narrative and documentary feature films and twenty-three shorts. In addition, the Festival chose three distinguished artists to receive its Silver Medallion Award. “Though we aren’t able to present our program in-person as planned, we still want to announce the lineup to bring attention to these brilliant films,” said Telluride Film Festival executive director Julie Huntsinger. “We’ve listed everything we know about screening opportunities so that audiences may watch as many of these films as possible. The Festival will continue to do everything in its power to champion and promote this artform and the people who create it.” Telluride Film Festival is proud to have selected the following new narrative and documentary feature films for its main program. THE SHOW AFTER LOVE (dir. Aleem Khan, UK, 89 min) ALL IN: THE FIGHT FOR DEMOCRACY (dir. Liz Garbus, Lisa Cortés, USA, 102 min) How to watch: In select theaters Sept. 9, available to stream on Amazon Prime Video Sept. 18 THE ALPINIST (dir. -

PREVIEW PRESS CONFERENCE FIRST HIGHLIGHTS of VIENNALE 2020 Vienna, August 20, 2020

PREVIEW PRESS CONFERENCE FIRST HIGHLIGHTS OF VIENNALE 2020 Vienna, August 20, 2020 Dear ladies and gentlemen, We are pleased to inform you about the current state of preparations for the Viennale 2020. This year, the Viennale will take place from October 22 to November 1. The existing documents present the first preview, as well as already established points of the program from the 58th edition of the Viennale. We also introduce the poster subject of the festival and the Retrospective. Continuously updated information can be found on our website www.viennale.at/en; press material and photos to download at viennale.at/en/press/download. For any further questions, please contact us. With kindest regards, The Viennale Press Team [email protected] Fredi Themel +43/1/526 59 47-30 Sadia Walizade +43/1/526 59 47-20 Accreditations, from August 21: Sadia Walizade +43/1/526 59 47-20 [email protected] (Accreditation applications accepted until October 2) viennale.at/en/press/accreditation VIENNALE – Vienna International Film Festival Siebensterngasse 2, 1070 Vienna • T +43/1/526 59 47 • F +43/1/523 41 72 [email protected] • viennale.at printed by VIENNALE 2020 OKTOBER 22—NOVEMBER 1 VIENNALE 2020 A Festival of Synergies, Collaborations and Coexistence Poster subject Trailer Textur #2 MONOGRAPHY SAY GOODBYE TO THE STORY Passages through Christoph Schlingensief’s Cinematic Work CINEMATOGRAPHIES ŽELIMIR ŽILNIK The Spirit of Solidarity AUSTRIAN AUTEURS The 1970s – A Film Decade on the Move AUSTRIAN DAYS RETROSPECTIVE RECYCLED CINEMA VIENNALE 2020 The 58th edition of the Viennale is taking place in a very unusual year. -

REVIEW 2013 - 2014 Dear Friend of Randall’S Island Park

REVIEW 2013 - 2014 Dear Friend of Randall’s Island Park, Thank you for your interest in Randall’s Island Park. As Co-Chairs of the Randall’s Island Park Alliance (RIPA) Board of Trustees, we invite you to enjoy our 2013-2014 Review. RIPA’s continued success in reaching our goals comes through the great work and generosity of our many partners and supporters – a true Alliance in support of the Park’s programs, fields, facilities and natural areas. You will find in the following pages photos and acknowledgements of the many local program partners, donors, volunteers, elected officials and City and State agencies who have helped to bring us to this point. We are especially grateful to the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation for extraordinary support and guidance throughout our successful partnership of more than 20 years. Following its recent transformation, Randall’s Island Park’s visibility continues to grow, and more and more New Yorkers are visiting its shores. Our fellow Board Members, challenged and inspired by what the Park can be, continue to contribute countless hours and crucial support. In 2014 the Board undertook a comprehensive plan for improvement and expansion of our free public programs. Visits to the Island have nearly doubled in recent years, to approximately 3 million! We expect our increased free programming will continue to expand our universe of visitors and friends. Many thanks to these millions of fans who visit and who compliment the Park through positive feedback on our social media, sharing photos and observations, and who help us to grow our Alliance every day. -

Potamkin Blackmore Bolton Dweck Press

MUSEUM OF ARTS AND DESIGN ANNOUNCES NEW TRUSTEES AND TREASURER Andi Potamkin Blackmore and Simon Bolton Elected New Trustees Michael Dweck Named Treasurer NEW YORK, NY (January 13, 2017) – The Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) announced today the appointment of two new Trustees: Andi Potamkin Blackmore and Simon Bolton. The Board of Trustees also named current Finance Committee Chair Michael Dweck Treasurer. The election took place at the December 8, 2016, board meeting. “The Board is thrilled to welcome new Trustees Andi Potamkin Blackmore and Simon Bolton, both of whom have made MAD a philanthropic priority,” said Michele Cohen, Chair of the Board. “Their demonstrated commitment to the fields of art and design and their audiences will support the Museum’s mission and visibility efforts.” In Dweck’s expanded role as Treasurer, “his financial expertise, leadership skills, and strategic acumen will serve him well in guiding the Museum in the next phase of its growth,” said Cohen. “We look forward to working with all three in their new roles.” Andi Potamkin Blackmore was elected Trustee in December 2016. A passionate champion of the arts, Potamkin Blackmore is the founder of Le Mise, a Brooklyn-based art and design advisory firm, as well as Three Squares Studio, a hair salon and art gallery in Manhattan, where she currently serves as Creative Director. She also works for the Potamkin Automotive Group, founded by her grandfather, Victor Potamkin, in 1954. Previously, she was the Potamkin in Kasher|Potamkin, a gallery and boutique in Chelsea. Potamkin Blackmore writes about art, design, well- being, and philosophy for publications including L’Oeil de la Photographie and 1stdibs and publishers including Glitterati Incorporated. -

For Immediate Release the 30Th Annual Florida Film

Media Contact: Valerie Cisneros [email protected] 407-629-1088 x302 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE 30TH ANNUAL FLORIDA FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES PROGRAM LINEUP Orlando, FL – (March 17, 2021) – Today the Florida Film Festival announced the program lineup for the 30th Annual Festival, April 9-22, 2021, happening online and in Maitland and Winter Park, Florida, with Primary Sponsor Full Sail University and Primary Public Partners Orange County Government and the Florida Division of Cultural Affairs. The Festival will screen 164 films representing 31 countries. Of the films selected, 151 have premiere status, including 23 world premieres. Full lineup listed below. Film descriptions, trailers, stills, and schedule available on our website here. “We are incredibly proud to have the opportunity to present these artists’ extraordinary work on both the big screen at Enzian and virtually as well,” commented Matthew Curtis, Florida Film Festival Programming Director. “The highest percentage of films ever (over 92%), will be making their Florida debut at the festival, and we could not be more thrilled about introducing these talented filmmakers and presenting such an entertaining and diverse group of films to our audience. This year’s lineup includes 90 women or non-binary filmmakers--the most in our 30-year history and 55% of our total programming--and their voices will be represented throughout every part of the festival. In addition, we have added a third live-action shorts program to the International Showcase for the first time ever, thereby giving our audience another terrific collection of films from abroad to experience. We are also excited that the virtual platform will allow almost all of these official selections to be available to festival-goers across the state of Florida. -

MODERNISM Inc. 685 Market Street, Ste

MODERNISM Inc. 685 Market Street, Ste. 290, San Francisco, CA 94105 Tel 415.541.0461 Fax 415.541.0425 Michael Dweck “Nymphs and Sirens” Thursday, May 7-June 27, 2015 Opening reception: Thursday, May 7th, from 5:30 to 8:00pm Modernism Presents a Multiform Collection of Work by Michael Dweck “The human body in motion is the ideal picture of the human soul” – Michael Dweck Modernism is pleased to present Nymphs and Sirens, a diverse collection of new and reimagined works by acclaimed American visual artist Michael Dweck. Since his childhood on Long Island’s cloistered shores, the sea has served as muse, subject and metaphor in Dweck’s art. It revealed itself as an Eden for the “forever young” surfers in 2004’s paradisiacal and symbolic The End: Montauk, N.Y., and appeared again as an abstract environment for the evasive female forms that populated 2009’s impressionistic Mermaids. Now, in his latest body of work, Nymphs and Sirens, Dweck, turns his focus to motion and medium, while carrying along reference points from the aforementioned sea-inspired collections. Scuptural Forms At the center of the new collection is a series of Sculptural Forms that feature photographs from Montauk and Mermaids printed on silk and coated with fiberglass and layers of high-gloss resin by skilled artisans to create beautiful, handmade surfboard-shaped sculptures that seamlessly merge Dweck’s subject and medium. “I love the implied movement of these forms, as well as the smooth, fluid shapes,” says Dweck. “They become vehicles that transport you to other places… I would like people to have a transporting experience with the work.” Mural Form Contrasting the subtle curves of the boards, is a Mural Form that renders one of Dweck’s “mermaids” larger than life, an apparition worthy of the Homeric legend. -

Exclusive: A&F's New Ruehl

SOUNDS OF STYLE, A SPECIAL REPORT/SECTION II WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • TheTHURSDAY Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • September 2, 2004 • $2.00 Sportswear A knit display in A&F’s latest format, Ruehl. Exclusive: A&F’s New Ruehl By David Moin informally more like a big man on campus than the NEW ALBANY, OHIO — The chairman wears jeans and flip- company chieftain, the approach to brand-building is flops to work and his 650 associates follow suit at the anything but casual. The intensity is as evident as sprawling, campus-style Abercrombie & Fitch ever with A&F’s latest retail brand and its Teutonic- headquarters here. sounding name, Ruehl. That’s just the veneer, though, because for Michael And Ruehl is just the first of three new retail Jeffries and the youthful army of workers he greets See New, Page 4 PHOTO BY DAVID TURNER DAVID PHOTO BY 2 WWD, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 2, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Hilton Launches Jewelry With Amazon Sportswear By Marc Karimzadeh GENERAL Paris Hilton in A&F ceo Michael Jeffries lays out the strategy for Ruehl, the firm’s latest chain “It’s just being a girl; every girl NEW YORK — her multicross aimed at post-college shoppers, set to open Saturday in Tampa, Fla. loves jewelry.” necklace. 1 It’s as simple as that for Paris Hilton, who on U.S. textile groups fired up the pressure on the Bush administration, saying Wednesday launched the Paris Hilton Collection of 2 they will file dozens of petitions to reimpose quotas on Chinese imports. jewelry in an exclusive agreement with Amazon.com. -

DOCUMENTARY SUGGESTIONS….MARCH 2021… 76 DAYS Rating – 3.5/5 the Opening Sequences Feel Like a Genre Movie — Science- Fiction, Zombie Horror, Apocalyptic Thriller

Aurora Film Circuit AFC Input – Personal review of the film (Nelia Pacheco Chair/Programmer, AFC) Synopsis – this info was gathered from different sources such as; TIFF, IMDb, Film Reviews etc. FILM TITEL and INFO AFC Input SYNOPSIS DOCUMENTARY SUGGESTIONS….MARCH 2021… 76 DAYS Rating – 3.5/5 The opening sequences feel like a genre movie — science- fiction, zombie horror, apocalyptic thriller. We watch Director/Editor: Hao Wu I saw this DOC back in Sept.2020 and it left hospital workers, encased in PPE so that we only see their USA, 2020 me calmer and in a more retrospective eyes behind foggy goggles, as they race from one patient Mandarin mindset re: COVID. Seeing the chaos, to another. At the hospital doors, a desperate crowd is 1H 33 minutes compassion, sadness and dedication from clamouring for entry. The overwhelmed workers can only the Health Care Providers during the start admit a few people at a time. Available:Paramount/YouTube/Gog of the pandemic allowed me to become For all the fantastical elements, this is the reality of gle Play Movies & TV even MORE grateful for our front line 2020. The filmmakers of 76 Days capture an invaluable workers - just how much they have & record of life inside Wuhan, China, ground zero for the Content advisories: illness, dead continue to endure during this pandemic, outbreak of COVID-19. On January 23, the city of 11 million bodies and what my role in all of this has been and people went into a lockdown that lasted 76 days. This film continues to be. -

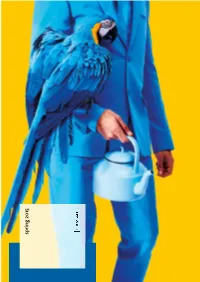

Spring 2015Spring 2015

[ spring 2015 spring 2015 spring 2015 index [ new titles 5 [ backlist 48 photography 49 toiletpaper 62 fashion | lifestyle 64 contemporary art 67 alleged press 74 freedman | damiani 75 standard press | damiani 76 factory 77 urban art 78 music 80 architecture | design 82 collector's edition 84 collecting 93 [ contacts 95 [ distributors 96 2 [ new titles ] [ spring 2015 ] 3 new titles the drugstore camera dennis hopper The Drugstore Camera feels like a stumbled-upon treasure, a disposable camera you forgot about and only just remembered to develop. Yet in this case the photographer is Dennis Hopper and the photographs, remarkably, are never before published. Shot in Taos, New Mexico, where Hopper was based following the production of Easy Rider in the late 60s, the series was tak- en with disposable cameras and developed in drugstore photo labs. This clothbound collection documents Hopper’s friends and family among the ruins and open vistas of the desert land- scape, female nudes in shadowy interiors, road trips to and from his home state of Kansas and impromptu still lifes of discarded objects. These images, capturing iconic individuals, wide-open Western terrain and drug-addled fun, create a captivating view of the 60s and 70s that combines political idealism and opti- mism with California cool. Dennis Hopper(1936–2010) was born in Dodge City, Kansas. He first appeared on television in 1954, and quickly became a cult actor, known for films such asRebel Without a Cause (1955), Easy Rider (1969), The American Friend (1977), Apocalypse Now (1979), Blue Velvet (1986) and Hoosiers (1986). In 1988, he directed the critically acclaimed Colors. -

Over Half a Million Dollars to Groundbreaking Documentary Projects

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: May 18, 2018 Spencer Alcorn 310.360.1981 [email protected] Sundance Institute: Over Half a Million Dollars to Groundbreaking Documentary Projects Twenty-Three Projects from Thirteen Countries Among Documentary Film Program’s Latest Grantees Los Angeles, CA — More than $585,000 in targeted grants will support a global crop of independent nonfiction storytellers, Sundance Institute announced today. 57% of the supported projects are helmed by women, and 48% are from outside the U.S.; 34% of grantees are first-time feature filmmakers. This cohort is one of two that will be announced this year; projects are selected as part of an ongoing rolling call. “These artists are hard at work on projects that capture the world as it is, as well as imagining it as it could be," said Hajnal Molnar-Szakacs, the recently-appointed Director of the Sundance Institute’s Documentary Film Fund. "The stories here deeply reflect my team's collaborative vision for this fund and we are thrilled to highlight voices with richly diverse sensibilities and perspectives. In our current cultural and political moment, independent storytelling is vital: to help make meaning and present a layered, complex interpretation of truth.” Sundance Institute has a long history and firm commitment to championing the most distinctive nonfiction films from around the world. Recently-supported films include Hale County This Morning This Evening; I Am Not Your Negro; Last Men in Aleppo; An Insignificant Man; Casting JonBenet; Strong Island; Hooligan Sparrow; Newtown and Weiner. More information is available at sundance.org/documentary. The 2018 Documentary Fund grantees are: DEVELOPMENT Body Parts (United States) Director: Kristy Guevara-Flanagan Producer: Helen Hood Scheer Body Parts (working title) is a documentary feature exploring the nude female body in Hollywood media—hyper-sexualized, under attack, exploited on- and off- screen. -

Contenders 2020 Schedule

Contenders 2020 Schedule December 10-15, 2020 - Opening Night Time. 2020. USA. Directed by Garrett Bradley Q&A with Legacy Russell, Associate Curator, Exhibitions, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and Garrett Bradley Courtesy of Amazon Studios December 15-20, 2020 First Cow. 2020. USA. Directed by Kelly Reichardt Q&A with Brittany Shaw, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Film, Kelly Reichardt, Jon Raymond (co-writer), and John Magaro (actor) Courtesy of A24 December 15-20, 2020 The Assistant. 2020. USA. Directed by Kitty Green Q&A with La Frances Hui, Curator, Department of Film, Kitty Green and Julia Garner (actor) Courtesy of Bleecker Street December 17-22, 2020 Kajillionaire. 2020. USA. Directed by Miranda July Q&A with Sophie Cavoulacos, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, Miranda July, Evan Rachel Wood (actor), Collier Schorr (photographer), Sonia Misra (scholar), and AJ Girard (curator) Courtesy of Focus Features December 17-22, 2020 Dick Johnson is Dead. 2020. USA. Directed by Kirsten Johnson Q&A with Rajendra Roy, Celeste Bartos Chief Curator of Film, and Kirsten Johnson Courtesy of Netflix December 17-22, 2020 Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Always. 2020. USA. Directed by Eliza Hittman Q&A with Sophie Cavoulacos, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, and Eliza Hittman Courtesy of Focus Features December 22-27, 2020 76 Days. 2020. USA/China. Directed by Hao Wu, Weixi Chen, Anonymous Q&A with La Frances Hui, Curator, Department of Film, and Hao Wu Courtesy of MTV Documentaries December 22-27, 2020 La nuit des rois (Night oF the Kings). 2020. France/Ivory Coast/Canada/Senegal. Directed by Philippe Lacôte Q&A with with Rajendra Roy, Celeste Bartos Chief Curator of Film, and Philippe Lacôte Courtesy of NEON December 22-27, 2020 The Forty Year-Old Version. -

Directed by Sam Feder Produced by Amy Scholder And

Directed by Sam Feder Produced by Amy Scholder and Sam Feder Executive Producers Laverne Cox, Caroline Libresco, Laura Gabbert, S. Mona Sinha, Abigail E. Disney, Lynda Weinman, Charlotte Cook, Michael Sherman, Matthew Perniciaro, WORLD PREMIERE 2020 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL Released globally on Netflix June 19, 2020 PRESS CONTACTS Netflix: Rene Ridinger [email protected] Acme PR: Nancy Willen [email protected] LOGLINE Disclosure shows how the fabled stories of Hollywood deeply influence how Americans feel about transgender people, and how trans people are taught to feel about themselves. SYNOPSIS Disclosure is an unprecedented, eye-opening look at transgender depictions in film and television, revealing how Hollywood simultaneously reflects and manufactures our deepest anxieties about gender. Leading trans thinkers and creatives, including Laverne Cox, Lilly Wachowski, Yance Ford, Mj Rodriguez, Jamie Clayton, and Chaz Bono, share their reactions and resistance to some of Hollywood’s most beloved moments. Grappling with films like A Florida Enchantment (1914), Dog Day Afternoon, The Crying Game, and Boys Don’t Cry, and with shows like The Jeffersons, The L-Word, and Pose, they trace a history that is at once dehumanizing, yet also evolving, complex, and sometimes humorous. What emerges is a fascinating story of dynamic interplay between trans representation on screen, society’s beliefs, and the reality of trans lives. Reframing familiar scenes and iconic characters in a new light, director Sam Feder invites viewers to confront unexamined assumptions, and shows how what once captured the American imagination now elicit new feelings. Disclosure provokes a startling revolution in how we see and understand trans people.