Impact Assessment: Introducing a Deposit Return Scheme On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

BUSINESS Magazine

ALBERTA School of BUSINESS Magazine University of Alberta PE PLE P WERED The Importance and Impact of Human Resources Leading the way from the ground up - LARRY POLLOCK Global recognition- FT MBA RANKINGS Why do people work? - BRUCE RIGAL WINTER 2015 Judith Athaide Gail Harding Donald Oborowsky The Cogent Group Inc. Canadian Western Bank Waiward Steel BUSINESS Calgary, Alberta Calgary, Alberta Fabricators Ltd. Edmonton, Alberta Eric Axford Brian Heidecker advisory Suncor Energy Inc. Sawridge Trusts Brian Pohl Calgary, Alberta Edmonton, Alberta Orthus Partners LLP London, United Kingdom council Linda Banister Richard Jenkins Banister Research Black Creek Investment Dr. John C Poon & Consulting Ltd. Management Inc. Broad Venture Edmonton, Alberta Toronto, Ontario International Ltd. Hong Kong The Business Advisory Robert Borrelli Ruth Kelly KPMG Venture Publishing Inc. Fred Singer Council was established Edmonton, Alberta Edmonton, Alberta Henry Singer Fashion Group Ltd. in 1980 with a mandate to J Lorne Braithwaite Michael Lang Edmonton, Alberta strengthen business and Park Avenue Holdings Ltd. StoneBridge Merchant Thornhill, Ontario Capital Corp. Alfred Sorensen management education Calgary, Alberta Pieridae Energy Ltd. Court Carruthers Calgary, Alberta at the University of Alberta. Grainger Neil Manning The council has been an Lake Forest, Illinois Coleridge Holdings Ltd. David Stevens Victoria, British Columbia EPCOR Utilities Inc. Joseph A Doucet extraordinarily valuable Edmonton, Alberta Alberta School of Business Linda McCurdy resource for this school. Edmonton, Alberta K-Bro Linen Systems Inc. Brian Vaasjo Edmonton, Alberta Capital Power Corp. Robert Fisher Edmonton, Alberta Alberta School of Business Amit Monga The council serves as a vital Edmonton, Alberta Alberta School of Business Kim Ward communications link among Toronto, Ontario Interward Asset Terry Freeman Management Ltd. -

FEBRUARY, 2010 First United Methodist Church Rocky Mount, North Carolina Cover Feature on Pages 30–31

THE DIAPASON FEBRUARY, 2010 First United Methodist Church Rocky Mount, North Carolina Cover feature on pages 30–31 Feb 2010 COVER.indd 1 1/13/10 8:15:37 AM Feb 2010 pp. 2-18.indd 2 1/13/10 8:17:07 AM THE DIAPASON Letters to the Editor A Scranton Gillette Publication One Hundred First Year: No. 2, Whole No. 1203 FEBRUARY, 2010 100th anniversary issue Seminary. When Arthur Carkeek taught Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 Thank you for the whimsical classi- at DePauw, I presented them to the li- An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, fi eds—they are a hoot! I look forward brary there, where I fervently hope they the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music to each issue. There is always news and still exist. Somewhere in a mid-60s issue informed discussion which expands my is a photo of me and Art Carkeek and the world, and I appreciate both the pedago- librarian at the time of the presentation. gy and the occasional humor to be found; Incidentally, I identifi ed all the people CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] in fact, everyone should subscribe to the on the cover correctly except for Rolan- 847/391-1045 magazine if for no other reason than that de Falcinelli. Kudos again. FEATURES it is a “good read.” Charles Huddleston Heaton Bedient update: The University of Iowa Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON Much of my new organ music is pur- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania by Jon Taylor 19 [email protected] chased on the basis of reviews in “New 847/391-1044 University of Michigan Historic Tour LVI Organ Music,” and the information is I am so thankful that I made contact Spain (Catalonia) and France, July 7–22 generally accurate and understandable with you in November, and “got back on by Timothy Huth 20 Contributing Editors LARRY PALMER Harpsichord enough that I can fi lter out what is suit- track” by restoring myself as a subscriber The Chopin Bicentennial: able for me, and I seldom regret the of The Diapason. -

100% Proof Addendum

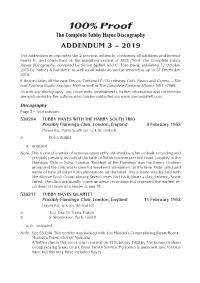

100% Proof The Complete Tubby Hayes Discography ADDENDUM 3 – 2019 This addendum incorporates the 2 previous addenda, containing all additions and amend- ments to, and corrections of, the published version of 100% Proof: The Complete Tubby Hayes Discography, compiled by Simon Spillett and C. Tom Davis, published 12 October 2015 by Names & Numbers, as well as all additions and amendments up to 31 December 2019. It thus includes all the new Decca/Fontana LP/CD releases Grits, Beans and Greens – The Lost Fontana Studio Sessions 1969 as well as The Complete Fontana Albums 1961 –1969. As with any discography, any comments, amendments, further information and corrections are welcomed by the authors who can be contacted via www.simonspillett.com. Discography Page 3 – Add sessions: 530204 TUBBY HAYES WITH THE HARRY SOUTH TRIO Possibly Flamingo Club, London, England 4 February 1953 Hayes (ts); Harry South (p); u/k (b) and (d) a Bud’s Bubble a unissued Note: This is one of a series of acetates apparently obtained by a fan actively recording and privately pressing records of the birth of British modern jazz first hand, possibly at the Flamingo Club in Soho, London. Resident at the Flamingo was the Kenny Graham group and the club was known for weekend ‘all-nighters’ at this time. Date, artist and name of tune all taken from annotations on the label. This acetate was backed with The Ronnie Scott Group playing Seven Eleven Part I & II/Night & Day/Trottin’/Scott Theme. The discs are aurally crude amateur recordings but represent the earliest re- cordings of Hayes as a leader at age 18. -

RADIO the STATION the STARS an Affectionate History of Nyearselt Broadcasffng by RICHARDNICHOLS

RADIO THE STATION THE STARS An Affectionate History of nYearselt Broadcasffng BY RICHARDNICHOLS RADIO LUXEMBOURG THE STATION OF THE STARS 1 RADIO LUXEMBOURG THE STATION OF THE STARS An Affectionate History of 50 Years of Broadcasting BY RICHARD NICHOLS A COMET BOOK Published by the Paperback Division of W.H. ALLEN & CO. LTD A Comet Book Published in 1983 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Howard & Wyndham Company 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB Copyright ©Richard Nichols, 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Hazell Watson & Viney Ltd, Aylesbury ISBN 0 86379 035 6 Acknowledgements A list of the names of all those who have helped would, at this juncture, be relatively pointless, since this book is itself a list of names, all of whom have been endlessly helpful. But otherwise without credit are a few people who have contributed enormously -Tony Fox, who has worked at least as hard as I have, Dave Atkey, as unselfishly generous as it's possible to be, and Lynn Cullen, who did all the tricky stuff with typewriters and photocopiers, plus licking the stamps. Quotations from BBC internal memorandaon pages 15, 16, 19-22, 24, 30-33, 37, 61 and 62are BBC copyright material reproduced by kind permission of The BBC Written Archive Centre, Caversham Park, Reading RG4 8TZ This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re -sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and withouta similar condition including this condition being imposedon the subsequent purchaser.