Race, Class, and the Postindustrial City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Econ 771.001

ECON 771: Political Economy of Race and Gender Spring 2018 Dr. Elissa Braunstein Department of Economics, Colorado State University [email protected] Office: C327 Clark Office hours: T 1:00 – 2:00 (or by appointment) Overview I define political economy as “the study of the impact of group identity and collective conflict on the organization of economic activity and its consequences.” Political economy traditions tend to focus on class as a source of identity and group conflict. In this course, we will expand that focus to incorporate other sources of group membership, giving you a broad background in economic approaches to inequality and identity based on race/ethnicity and gender. We will focus primarily on the neoclassical, Marxian political economy and feminist literatures. In addition to learning more about the relationship between group membership and economic structures, we will use the prisms of race and gender to better understand and critique various approaches to economic analysis. And while much of the literature focuses on the U.S. context, I will try to broaden the discussion as often as possible, and encourage students to do the same. I welcome students from other social science disciplines. Although we will cover some advanced material that may be difficult for those who have not completed graduate economics courses, the emphasis will be on the main points, rather than the technical detail. The syllabus includes both required readings (*starred) and supplemental readings/sections as I wanted to give you a more complete sense of the literature if you are interested in looking further into a particular topic. -

Will Look Primarily for Reasons Families Changed, and Why They Appear To

The Growing Differences in Family Structure: What Do We Know? Where Do We Look for Answers? By David T. Ellwood and Christopher Jencks John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University August 2001 This paper was prepared as part of the New Inequality Program supported by the Russell Sage Foundation. The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous support for this initiative. Eric Wanner provided helpful comments. Thank you to Elisabeth Welty, Chris Wimer, and David Harding for their excellent research work and thoughtful suggestions and to Seth Kirshenbaum for his careful editing and fine assistance. The Growing Differences in Family Structure: What Do We Know? Where Do We Look for Answers? By David T. Ellwood and Christopher Jencks The rapid changes in family structure in the United States over the past 40 years have unquestionably contributed to growing family income inequality. One mechanism is quite well known. The growth of single parenthood tends to raise poverty and lower family incomes if for no other reason than more children are being supported by only one potential earner who is usually a woman. What is far less well known is the fact that single parenthood has grown quite differently by the level of maternal education. For a women aged 25-34 in the bottom third of the education distribution, the odds of being a single parent has risen from 7% in the mid 1960s to nearly 20% today. For a comparably aged woman in the top third of education, the odds have barely changed from the 5% figure of the 1960s. In spite of a few high profile celebrity cases, single parenthood remains rare for this educated group. -

The Millennium Breach the American Dilemma, Richer and Poorer

The Millennium Breach The American Dilemma, Richer and Poorer In Commemoration of the Thirtieth Anniversary of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders Executive Summary Second Edition, 1998 The Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation and The Corporation for What Works "Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal." On March 1, 1968, in the wake of riots in Detroit and Newark, and with more riots soon to come after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, that was the conclusion of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders—the Kerner Riot Commission, named after its chair, then-governor of Illinois Otto Kerner. Thirty years to the day, on March 1, 1998, the Milton S. Eisenhower Foundation released an update of the Kerner Commission. This is the second edition to the update. The original Commission concentrated on African-Americans and inner cities. To provide continuity, much of this update is similarly focused. At the same time, the report is sensitive to rapidly expanding disparities in income and wealth that are class-based, embraces all inner city minorities in poverty, and respects today's more complex, multicultural diversity—particularly the growing proportions of Hispanics and Asian- Americans in urban areas. The report tries to answer these questions: • What happened over the last thirty years? What are the facts on which to build an inner city policy for the new millennium? • What policy doesn't work? • What policy works? • What is the cost of replicating what works to scale and how can it be financed? • What are the major political obstacles against replicating to scale? • What is the political feasibility of a policy based on what works? • What political alliance is needed to generate political will? What Are The Facts? The Kerner Commission proposed remedies to racial, spatial and economic disparity. -

Recipients of Asa Awards

APPENDIX 133 APPENDIX 11: RECIPIENTS OF ASA AWARDS MacIver Award 1956 E. Franklin Frazier, The Black Bourgeoisie (Free Press, 1957) 1957 no award given 1958 Reinhard Bendix, Work and Authority in Industry (Wiley, 1956) 1959 August B. Hollingshead and Frederick C. Redlich, Social Class and Mental Illness: A Community Study (Wiley, 1958) 1960 no award given 1961 Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Doubleday, 1959) 1962 Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics (Doubleday, 1960) 1963 Wilbert E. Moore, The Conduct of the Corporation (Random House, 1962) 1964 Shmuel N. Eisenstadt, The Political Systems of Empires (Free Press of Glencoe, 1963) 1965 William J. Goode, World Revolution and Family Patterns (Glencoe, 1963) 1966 John Porter, The Vertical Mosaic: An Analysis of Social Class and Power in Canada (University of Toronto, 1965) 1967 Kai T. Erikson, Wayward Puritans (Wiley, 1966) 1968 Barrington Moore, Jr., Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Beacon, 1966) Sorokin Award 1968 Peter M. Blau, Otis Dudley Duncan, and Andrea Tyree, The American Occupational Structure (Wiley, 1967) 1969 William A. Gamson, Power and Discontent (Dorsey, 1968) 1970 Arthur L. Stinchcombe, Constructing Social Theories (Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1968) 1971 Robert W. Friedrichs, A Sociology of Sociology; and Harrison C. White, Chains of Opportunity: Systems Models of Mobility in Organization (Free Press, 1970) 1972 Eliot Freidson, Profession of Medicine: A Study of the Sociology of Applied Knowledge (Dodd, Mead, 1970) 1973 no award given 1974 Clifford Geertz, The Interpretation of Cultures (Basic, 1973); and Christopher Jencks, Inequality (Basic, 1972) 1975 Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World System (Academic Press, 1974) 1976 Jeffrey Paige, Agrarian Revolution: Social Movements and Export Agriculture in the Underdeveloped World (Free Press, 1975); and Robert Bellah, The Broken Covenant: American Civil Religion in Time of Trial (Seabury Press, 1975) 1977 Kai T. -

PAA Oral History Project Volume 1--Presidents Number 2

DDEEMMOOGGRRAAPPHHIICC DDEESSTTIINNIIEESS Interviews with Presidents and Secretary-Treasurers of the Population Association of America PAA Oral History Project Volume 1--Presidents Number 2--From 1961 through 1976 Prepared by Jean van der Tak PAA Historian 1982 to 1994 Assembled for Distribution by the PAA History Committee: John R. Weeks, Chair (PAA Historian, 1994 to present) Paul Demeny David Heer Dennis Hodgson Deborah McFarlane 2005 ABOUT THE PAA ORAL HISTORY PROJECT AND THESE INTERVIEWS This series of interviews with past presidents and secretary-treasurers and a few others for the oral history project of the Population Association of America is the brainchild of Anders Lunde, without whom PAA would scarcely have a record of its 60year history. Dismayed by the dearth of usable PAA files he inherited as secretary-treasurer in 1965-68, Andy later determined to capture at least the reminiscences of some of PAA's longest-time members. When written pleas yielded few results, he set about doing taped interviews with past presidents and secretary-treasurers and conducted over a dozen (with help from Abbott Ferriss and Harry Rosenberg) between 1973 and 1979. Andy also assembled core records of meetings, membership numbers and officers and Board members since PAA's founding in 1931. He established PAA's official archives and arranged--with the help of Tom Merrick and Conrad Taeuber--for their cataloguing and deposit in the Georgetown University library. [Note: the archives were removed from Georgetown University in the late 1990s, and are now housed in a storage unit rented by the Population Association of America, accessible through the Executive Director of the PAA.] With Con Taeuber, he organized the "PAA at Age 50" session at the 1981 50th anniversary meeting in Washington, which produced four valuable papers on early PAA history by Frank Notestein, Frank Lorimer, Clyde Kiser, and Andy himself (published in Population index, Fall 1981). -

Underclass": Confronting America's Enduring Apartheid

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 1995 Integrating the "Underclass": Confronting America's Enduring Apartheid Olatunde C.A. Johnson Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Olatunde C. Johnson, Integrating the "Underclass": Confronting America's Enduring Apartheid, 47 STAN. L. REV. 787 (1995). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2207 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK NOTE Integrating the "Underclass": Confronting America's Enduring Apartheid Olati Johnson* AMERICAN APARTHEID: SEGREGATION AND THE MAKING OF THE UNDERCLASS. By Douglas S. Masseyt & Nancy A. Denton.t Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. 1993. 292 pp. $14.95. Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton's American Apartheid argues that housing integration has inappropriatelydisappeared from the nationalagenda and is critical to remedying the problems of the so-called "underclass." Re- viewer Olati Johnson praises the authors' refusal to dichotomize race and class and the roles both play in creatingand maintaininghousing segregation. However, she argues, Massey and Dentonfail to examine critically either the concept of the underclass or the integration ideology they espouse. Specifi- cally, she contends, the authorsfail to confront the limits of integration strate- gies in providing affordable housing or combating the problem of tokenism. -

Socialtheory from Marx to Parsons

«h ßÕþ Social eory from Marx to Parsons Kieran Healy [email protected] Fall óþóþ. Languages óÕÕ, allegedly. Wednesdays Õþ:Õ¢am–Õó:¦¢pm. Say what you mean. Bear witness. Iterate. John M. Ford, “De Vermis”. h¶§«u ou«h§£± is graduate-level course is an intensive introduction to some main themes in social theory. It is the rst of a two-part sequence required of rst year Ph.D students in the sociology department. It is a not a general introduction to the history of social or political thought. For the purposes of the course, “social theory” is work that has been inuential within the discipline of sociology. Even if you may not see much of this work directly “used” in current work, a good understanding of it is necessary for graduate students hoping to have any sort of informed understanding of how people in the discipline think, and why they think that way. Indirectly, we will also try to self-consciously develop habits of reading, thinking, and discussing the material that are intellectually productive rather than sterile, generative rather than merely “critical”, and on the whole scholarly rather than stupid. Õ add4693 on 2019/08/21 ó §u¤¶§uu±« Zo uì£uh±Z±« is is a graduate seminar. I take it for granted that you have a basic interest in the material, an enthusiastic attitude toward participation, and a respectful attitude to your peers. I expect you to attend each meeting, do the reading thoroughly and in advance, and participate actively in class. Participating actively means contributing to class discussion, something that involves both speaking and listening. -

“Class Cluelessness”

MONTAGE the resentment of ru- “Class Cluelessness” ral voters toward the White Working Class: “liberal elite” in The Overcoming Class The powerful resentments shaping American politics today Politics of Resentment: Cluelessness in America, Rural Consciousness in by Joan C. Williams by andrea louise campbell Wisconsin and the Rise (Harvard Business of Scott Walker (2016). Review Press, $22.99) J.D. Vance described onald J. trump’s victory in elites? Or does the logic of the Electoral Col- his own family’s predilections in Hillbilly the 2016 presidential election lege require a cross-racial, geographically di- Elegy (2016) and sociologist Arlie Russell spawned a maelstrom of finger- verse coalition of the non-elite centered on Hochschild reported that right-leaning folks D pointing and soul-searching with- economic issues? The analyses and recom- in Louisiana bayou country felt they were in the Democratic Party. How could the party mendations intended to prevent another 2016 Strangers in Their Own Land. Economist Robert of FDR, LBJ, and, for that matter, Bill Clinton, for the Democrats are just beginning. J. Gordon ’62 revealed why they might be so have lost touch so thoroughly with the white Pre-election warnings weren’t lacking. upset in The Rise and Fall of American Growth (re- working class that had been central to its co- A host of books detailed the growing dis- viewed in the May-June 2016 issue, page 68). alition for years? Which way should the party contents of lower-income white workers. If Democratic Party elites (and Hillary go in its identity and future strategy? Should Harvard political scientists Vanessa Wil- Clinton’s campaign officials) missed the it veer left, in the Bernie Sanders direction, liamson and Theda Skocpol wrote of the warning signs, Joan C. -

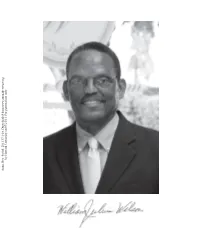

Reflections on a Sociological Career That Integrates Social Science With

SO37-Frontmatter ARI 11 June 2011 11:38 by Harvard University on 07/21/11. For personal use only. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011.37:1-18. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org SO37CH01-Wilson ARI 1 June 2011 14:22 Reflections on a Sociological Career that Integrates Social Science with Social Policy William Julius Wilson Kennedy School and Department of Sociology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011. 37:1–18 Keywords First published online as a Review in Advance on race and ethnic relations, urban poverty, social class, affirmative March 1, 2011 action, public policy, public agenda research The Annual Review of Sociology is online at soc.annualreviews.org Abstract by Harvard University on 07/21/11. For personal use only. This article’s doi: This autobiographical essay reflects on my sociological career, high- 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102510 lighting the integration of sociology with social policy. I discuss the Copyright c 2011 by Annual Reviews. personal, social, and intellectual experiences, ranging from childhood Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2011.37:1-18. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved to adult life, that influenced my pursuit of studies in race and ethnic re- 0360-0572/11/0811-0001$20.00 lations and urban poverty. I then focus on how the academic and public reaction to these studies increased my concerns about the relationship between social science and public policy, as well as my attempts to make my work more accessible to a general audience. In the process, I discuss how the academic awards and honors I received based on these studies enhanced my involvement in the national policy arena. -

An Exploratory Study of Free Will in the Social Sciences

AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF FREE WILL IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES A Thesis Presented to The Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs at Ashland University In Partial Fulfillment of the Program Requirement for Ashbrook Students Michael Byrne April, 2011 © 2011 Michael Byrne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract This study is an exploratory analysis of the belief in free will within the social sciences. While free will is a common topic in many fields, currently, very little research has investigated this topic. As such, this study was based on the assumption that no statistical difference would be found between the social sciences on belief in free will. To investigate this hypothesis, a historical case study was used to analyze belief in free will among professionals in the social science fields. Three general problems were addressed. First, this study examined the consistency of the belief in free will or determinism across the major divisions of the soft sciences. Second, this investigation highlighted the differences found within anthropology and political science. Lastly, consistency and inconsistency in the belief of free will and determinism within the social sciences was discussed. Significance was found in political science and anthropology. Two potential implications are addressed for these findings. Firstly, anthropology and political science may not accurately be classified as social sciences. Secondly, a mobius model was introduced to explain the natural flow of quantitative and qualitative methods that define the social sciences. These results provide an understanding of the social sciences beliefs concerning free-will. As no research has investigated belief in this way before, this research provides a basis for further research. -

Immigration, African American Segregation, and Arrest Changes in U.S

Immigration, African American Segregation, and Arrest Changes in U.S. Metropolitan Statistical Areas, 1980-2000. Michael E. Roettger National Center for Marriage Research Bowling Green State University August 2008 1 Abstract: Existing empirical research suggests that (1) immigrants commit less crime than non- immigrants, and (2) segregated and impoverished blacks in urban ghettoes are disproportionately more likely to commit crime. However, to date, no studies have tested how these relationships may spatially hold within urban areas. In this essay, I use a longitudinal sample of urban metropolitan areas to test if changes in immigrant populations and residential black populations are associated with changes in crime within urban areas. Findings may help to better contextualize existing literature on immigrant assimilation and the empirical literature linking crime and residential segregation within urban areas. 2 I. Introduction A decade ago, William Julius Wilson (1996) analyzed crime in Chicago neighborhoods where urban ghettoes of high unemployment and poverty were associated with a host of negative outcomes, including drug use, violent crime, dropping out of high school, and chronic unemployment. Wilson’s analysis demonstrated that African Americans suffered greatly from living within such urban ghettoes. Along with Wilson’s contemporary research, much work has been directed towards understanding and documenting the consequences of segregation. A key thread in this research has been the spatial mismatch between jobs and African Americans (Dworak-Fisher 2004; Edelman, Holzer, and Offner 2006; Massey and Denton 1994; Mouw 2000; Wilson 1987, 1996). Recent research has noted the high disparities in incarceration observed between blacks and whites, with an association of crime to low wages and high unemployment. -

BBG) As of 07-February-2011

Description of document: Listing of all prewritten obituaries of notable individuals prepared by the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) as of 07-February-2011 Requested date: 03-October-2010 Released date: 22-February-2011 Posted date: 14-March-2011 Date/date range of document: 1982-2011 Source of document: BBG, FOIA/PA Unit Room 3349 330 Independence Ave. SW Washington, D.C. 20237 Fax: (202) 203-4585 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Broadcasting Board of Governors 330 Independence Ave. SW T 202.203.4550 United States