The Enigma of Gülchatai's Face Or the Face of the Other

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nothing to Lose but Their Veils Failure and ‘Success’ of the Hujum in Uzbekistan, 1927-1953

Nothing to Lose but Their Veils Failure and ‘Success’ of the Hujum in Uzbekistan, 1927-1953 Word count: 25,896 Maarten Voets Student number: 01205641 Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Rozita Dimova, Prof. Dr. Bruno De Cordier A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in East European Languages and Cultures. Academic year: 2016 – 2017 August, 2017 2 Abstract The title of this work is a reference to Marx’ famous quote, ‘The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains.’ When the proletariat eventually took over control of the former Russian Empire after the October Revolution and the subsequent Russian civil war (1917 – 1923), they had to spread the revolution to the periphery; Central Asia. To gain support in Uzbekistan from the local (female) population the Communist Party commenced the Hujum campaign on the 8th of March 1927. This campaign targeted traditions that they considered derogatory to women, in particular the wearing of the local veil, or ‘paranja’. The campaign was a complete failure due to vehement Uzbek resistance. Yet, nowadays the paranja is little more than a museum piece. The veil disappeared from the street view from the 1950’s onwards. In my research I want to give an explanation for this delayed success. Yet, in a way the Hujum still carries on: both Central Asian and Western countries have a mixed stance on the modern variants of the paranja, as shown in the existence of burqa bans. I have analysed relevant events (such as Stalin’s purges, deportations, the battle against the Basmachi) from before, during, and after the initial Hujum and placed them inside a Gramscian framework to explain their effects on the civil and political society in Uzbekistan. -

Boys in Zinc on Trial Follow Penguin PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

Svetlana Alexievich BOY S I N Z I N C Translated by Andrew Bromfield Contents Prologue From the Notebooks Day One ‘For many shall come in my name …’ Day Two ‘And another dieth in the bitterness of his soul …’ Day Three ‘Regard not them that have familiar spirits, neither seek after wizards …’ Post Mortem Boys in Zinc on Trial Follow Penguin PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS BOYS IN ZINC Svetlana Alexievich was born in Ivano-Frankivsk in 1948 and has spent most of her life in the Soviet Union and present- day Belarus, with prolonged periods of exile in Western Europe. Starting out as a journalist, she developed her own non-fiction genre which brings together a chorus of voices to describe a specific historical moment. Her works include The Unwomanly Face of War (1985), Last Witnesses (1985), Boys in Zinc (1991), Chernobyl Prayer (1997) and Second-Hand Time (2013). She has won many international awards, including the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature for ‘her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time’. Andrew Bromfield earned his degree in Russian Studies at Sussex University and lived in Russia for several years. He has been a full-time translator of Russian literature for more than thirty years and is best known for translating modern authors, but his work also includes books on Russian art, Russian classics and non–fiction, with a range from Tolstoy to the Moscow Conceptualism Movement. On 20 January 1801 the Cossacks of the Don Hetman Vasily Orlov were ordered to march to India. A month was set for the stage as far as Orenburg, and three months to march from there ‘via Bukharia and Khiva to the Indus River’. -

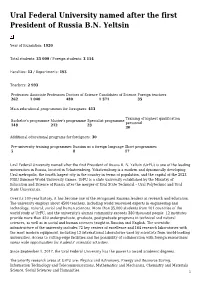

Ural Federal University Named After the First President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin

Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B.N. Yeltsin Year of foundation: 1920 Total students: 35 000 / Foreign students: 3 114 Faculties: 12 / Departments: 193 Teachers: 2 993 Professors Associate Professors Doctors of Science Candidates of Science Foreign teachers 262 1 040 480 1 571 35 Main educational programmes for foreigners: 413 Training of highest qualification Bachelor's programme Master's programme Specialist programme personnel 148 212 23 30 Additional educational programs for foreigners: 30 Pre-university training programmes Russian as a foreign language Short programmes 5 8 17 Ural Federal University named after the first President of Russia B. N. Yeltsin (UrFU) is one of the leading universities in Russia, located in Yekaterinburg. Yekaterinburg is a modern and dynamically developing Ural metropolis, the fourth largest city in the country in terms of population, and the capital of the 2023 FISU Summer World University Games. UrFU is a state university established by the Ministry of Education and Science of Russia after the merger of Ural State Technical – Ural Polytechnic and Ural State Universities. Over its 100-year history, it has become one of the recognized Russian leaders in research and education. The university employs about 4500 teachers, including world renowned experts in engineering and technology, natural, social and human sciences. More than 35,000 students from 101 countries of the world study at UrFU, and the university's alumni community exceeds 380 thousand people. 12 institutes provide more than 450 undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate programs in technical and natural sciences, as well as in social and human sciences taught in Russian and English. -

A Cultural Analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot

A CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RUSSO-SOVIET ANEKDOT by Seth Benedict Graham BA, University of Texas, 1990 MA, University of Texas, 1994 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2003 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Seth Benedict Graham It was defended on September 8, 2003 and approved by Helena Goscilo Mark Lipovetsky Colin MacCabe Vladimir Padunov Nancy Condee Dissertation Director ii Copyright by Seth Graham 2003 iii A CULTURAL ANALYSIS OF THE RUSSO-SOVIET ANEKDOT Seth Benedict Graham, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2003 This is a study of the cultural significance and generic specificity of the Russo-Soviet joke (in Russian, anekdot [pl. anekdoty]). My work departs from previous analyses by locating the genre’s quintessence not in its formal properties, thematic taxonomy, or structural evolution, but in the essential links and productive contradictions between the anekdot and other texts and genres of Russo-Soviet culture. The anekdot’s defining intertextuality is prominent across a broad range of cycles, including those based on popular film and television narratives, political anekdoty, and other cycles that draw on more abstract discursive material. Central to my analysis is the genre’s capacity for reflexivity in various senses, including generic self-reference (anekdoty about anekdoty), ethnic self-reference (anekdoty about Russians and Russian-ness), and critical reference to the nature and practice of verbal signification in more or less implicit ways. The analytical and theoretical emphasis of the dissertation is on the years 1961—86, incorporating the Stagnation period plus additional years that are significant in the genre’s history. -

Mediaobrazovanie) Media Education (M Ediaobrazovanie

Media Education (Mediaobrazovanie) Has been issued since 2005. ISSN 1994–4160. E–ISSN 1994–4195 2020, 60(1). Issued 4 times a year EDITORIAL BOARD Alexander Fedorov (Editor in Chief ), Prof., Ed.D., Rostov State University of Economics (Russia) Imre Szíjártó (Deputy Editor– in– Chief), PhD., Prof., Eszterházy Károly Fõiskola, Department of Film and Media Studies. Eger (Hungary) Ben Bachmair, Ph.D., Prof. i.r. Kassel University (Germany), Honorary Prof. of University of London (UK) Oleg Baranov, Ph.D., Prof., former Prof. of Tver State University Elena Bondarenko, Ph.D., docent of Russian Institute of Cinematography (VGIK), Moscow (Russia) David Buckingham, Ph.D., Prof., Loughborough University (United Kingdom) Emma Camarero, Ph.D., Department of Communication Studies, Universidad Loyola Andalucía (Spain) Irina Chelysheva, Ph.D., Assoc. Prof., Anton Chekhov Taganrog Institute (Russia) Alexei Demidov, head of ICO “Information for All”, Moscow (Russia) Svetlana Gudilina, Ph.D., Russian Academy of Education, Moscow (Russia) Tessa Jolls, President and CEO, Center for Media Literacy (USA) Nikolai Khilko, Ph.D., Omsk State University (Russia) Natalia Kirillova, Ph.D., Prof., Ural State University, Yekaterinburg (Russia) Sergei Korkonosenko, Ph.D., Prof., faculty of journalism, St– Petersburg State University (Russia) Alexander Korochensky, Ph.D., Prof., faculty of journalism, Belgorod State University (Russia) W. James Potter, Ph.D., Prof., University of California at Santa Barbara (USA) Robyn Quin, Ph.D., Prof., Curtin University, Bentley, WA (Australia) Alexander Sharikov, Ph.D., Prof. The Higher School of Economics, Moscow (Russia) Vladimir Sobkin, Acad., Ph.D., Prof., Head of Sociology Research Center, Moscow (Russia) Kathleen Tyner, Assoc. Prof., Department of Radio– Television– Film, The University of Texas at Austin (USA) Svetlana Urazova, PhD., Assoc. -

And Post-Soviet Literature and Culture

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Russia Eternal: Recalling The Imperial Era In Late- And Post-Soviet Literature And Culture Pavel Khazanov University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Eastern European Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Khazanov, Pavel, "Russia Eternal: Recalling The Imperial Era In Late- And Post-Soviet Literature And Culture" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2894. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2894 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2894 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Russia Eternal: Recalling The Imperial Era In Late- And Post-Soviet Literature And Culture Abstract The return of Tsarist buildings, narratives and symbols has been a prominent facet of social life in post- Soviet Russia. My dissertation aims to explain this phenomenon and its meaning by tracking contemporary Russia’s cultural memory of the Imperial era. By close-reading both popular and influential cultural texts, as well as analyzing their conditions of production and reception, I show how three generations of Russian cultural elites from the 1950s until today have used Russia’s past to fight present- day political battles, and outline how the cultural memory of the Imperial epoch continues to inform post- Soviet Russian leaders and their mainstream detractors. Chapters One and Two situate the origin of Russian culture’s current engagement with the pre-Revolutionary era in the social dynamic following Stalin’s death in 1953. -

Russian Cinema: a Very Short Story

Zhurnal ministerstva narodnogo prosveshcheniya, 2018, 5(2) Copyright © 2018 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. Published in the Slovak Republic Zhurnal ministerstva narodnogo prosveshcheniya Has been issued since 2014. E-ISSN: 2413-7294 2018, 5(2): 82-97 DOI: 10.13187/zhmnp.2018.2.82 www.ejournal18.com Russian Cinema: A Very Short Story Alexander Fedorov a , a Rostov State University of Economics, Russian Federation Abstract The article about main lines of russian feature film history: from 1898 to modern times. The history of Russian cinema goes back more than a century, it knew the stages of rise and fall, ideological repression and complete creative freedom. This controversial history was studied by both Russian and foreign scientists. Of course, Soviet and Western scientists studied Soviet cinema from different ideological positions. Soviet filmmakers were generally active in supporting socialist realism in cinema, while Western scholars, on the contrary, rejected this method and paid great attention to the Soviet film avant-garde of the 1920s. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the situation changed: russian and foreign film historians began to study cinema in a similar methodological manner, focusing on both ideological and socio-cultural aspects of the cinematographic process. Keywords: history, film, movie, cinema, USSR, Russia, film historians, film studies. 1. Introduction Birth of the Russian "Great Mute" (1898–1917). It is known that the French brought the movies to Russia. It was at the beginning of 1896. However, many Russian photographers were able to quickly learn a new craft. Already in 1898, documentary plots were shot not only by foreign, but also by Russian operators. -

Success Story

SUCCESS STORY Success means achieving good and expected results or the desired outcome of some event. Success comes natural as there can be no eventualities in operation of any company. A company’s operation repre- sents a sequence of causes and effects. One just needs to see the correct relation between events and use it for his own ends. A company brings together different persons forming a team. As part of the company we determine what our life will be in the company and beyond with our thoughts, feelings and actions. «The weak trust in luck and the strong trust in cause and effect» (R. Emerson), «Winners do not believe in an eventuality» (F. Nietzsche) — speaking of success said philosophers. Successes achieves by IBA-MOSCOW on certain days have analogues in the world history. Successes achieved in different periods of time and in different countries are in some way connected, influence each other and pave an uninterrupted path towards progress of our society. CONTENTS 1. Chairman of the Board address 5 Summing up the Bank’s performance in 2010 and plans for the future 5 2. General information about the Bank 9 Brief data 9 Mission, goals and corporate values 10 Administration 11 Members of the board 12 Management 12 Main developments in 2010 12 Charity and sponsorship programs 12 Ratings and awards 13 Membership in organizations 13 3. External environment 15 Global economy and international markets 15 Financial situation in the Russian Federation in 2010 16 Overview of the Russian banking sector in 2010 16 4. Bank's operations in 2010 19 Overall financial performance 19 Corporate business 21 Customer lending 25 Retail business 27 Operations in financial markets 31 5. -

Dear Friends! on Behalf of Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation I

ƒÓÓ„Ë ‰ÛÁ¸ˇ! Dear friends! ŒÚ ËÏÂÌË ÃËÌËÒÚÂÒÚ‚‡ ÍÛθÚÛ˚ –ÓÒÒËÈÒÍÓÈ On behalf of Ministry of Culture of the Russian ‘‰‡ˆËË ÔÓÁ‰‡‚Ρ˛ ‚‡Ò Ò Ì‡˜‡ÎÓÏ ‡·ÓÚ˚ Federation I would like to congratulate you all on 19-„Ó ŒÚÍ˚ÚÓ„Ó ÓÒÒËÈÒÍÓ„Ó ÍËÌÓÙÂÒÚË‚‡Îˇ the opening of the 19-th Open Russian Film "üËÌÓÚ‡‚". Festival "Kinotavr". ‘ÂÒÚË‚‡Î¸ ‚ —Ó˜Ë ‚Ò„‰‡ ·˚Î Ò‡Ï˚Ï ˇÍËÏ, The Festival in Sochi has always been the most Ò‡Ï˚Ï ÓÊˉ‡ÂÏ˚Ï, Ò‡Ï˚Ï Î˛·ËÏ˚Ï vivid, most anticipated, most admired and most Ô‡Á‰ÌËÍÓÏ Ë ÒÓ·˚ÚËÂÏ Ì‡ˆËÓ̇θÌÓ„Ó ÍËÌÓ. celebrated event for national cinema. But it is Œ‰Ì‡ÍÓ ËÏÂÌÌÓ ÚÂÔ¸, ̇ ‚ÓÎÌ ‡Òˆ‚ÂÚ‡ only now when domestic film industry is ÓÚ˜ÂÒÚ‚ÂÌÌÓ„Ó ÍËÌÓËÒÍÛÒÒÚ‚‡, "üËÌÓÚ‡‚" blooming, "Kinotavr" has become the main ÒÚ‡ÌÓ‚ËÚÒˇ „·‚ÌÓÈ ÔÓÙÂÒÒËÓ̇θÌÓÈ professional platform for the first-night showings, Ô·ÚÙÓÏÓÈ ‰Îˇ ÔÂϸÂÌ˚ı ÔÓÒÏÓÚÓ‚, meetings and discussions for all creative ‚ÒÚ˜ Ë ‰ËÒÍÛÒÒËÈ ‚ÒÂı Ú‚Ó˜ÂÒÍËı ÔÓÍÓÎÂÌËÈ generations of Russian cinematographers. ÓÒÒËÈÒÍËı ÍËÌÂχÚÓ„‡ÙËÒÚÓ‚. Participation in festival's programme is already an ”˜‡ÒÚË ‚ ÍÓÌÍÛÒÌÓÈ ÔÓ„‡ÏÏ "üËÌÓÚ‡‚‡" achievement, already success for every creative Ò‡ÏÓ ÔÓ Ò· ˇ‚ΡÂÚÒˇ ÛÒÔÂıÓÏ ‰Îˇ ÒÓÁ‰‡ÚÂÎÂÈ person in our film industry. To win at "Kinotavr" ͇ʉÓÈ ËÁ ‚˚·‡ÌÌ˚ı ÎÂÌÚ. œÓ·Â‰‡ ̇ beyond doubt means to receive the best ever proof "üËÌÓÚ‡‚Â" ÒÚ‡ÌÓ‚ËÚÒˇ ·ÂÒÒÔÓÌ˚Ï of innovation and craftsmanship and excellence. -

RUSS 330 Russian Cinema

1 RUSS 330 Russian Cinema Olga Dmitrieva Course Information Office: SC 166 Fall 2018 Phone: 4-9330 Tue-Thu 12:30-1:20pm REC 308 Email: [email protected] Screening Wed 6:30-9:20pm SC 239 Office Hours: Tue, Thu 1:30-2:30 pm Course Description This course is an introduction to the cinema of Russia from the Revolution of 1917 to the beginning of the 21st century. We will focus on the cinematic artistry of the films we discuss, while also working to place them in the context of profound political, historical, and cultural changes. Class is primarily discussion-based. No knowledge of Russian or background in Russian studies is required. Required Texts There is no single required textbook. Readings will be accessible online through Purdue library or made available via Blackboard. Text available online through Purdue library: The Russian Cinema Reader David Gillespie Russian Cinema Russian classical literature today: the challenges/trials Messianism and mass culture Course Requirements Participation Since the course format is largely discussion, you should come to class having done the reading and the viewing, and ready to share your thoughts and engage with the ideas of your classmates. You need to be present, be prepared, and be an active participant. Readings Readings will be assigned for each week’s module, to be completed by Tuesday. Weekly quizzes Every Tuesday class will begin with a short quiz testing your knowledge of the reading assigned for that week. Discussion prompts 2 Each film will be accompanied by a list of questions to be reviewed before screening. -

Cinema of the Thaw (1953 – 1967)

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Book Chapters Arts and Sciences 11-15-2013 Cinema of the Thaw (1953 – 1967) Alexander V. Prokhorov College of William & Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Modern Languages Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Prokhorov, A. V. (2013). Cinema of the Thaw (1953 – 1967). Rimgaila Salys (Ed.), The Russian Cinema Reader: Volume II, The Thaw to the Present (pp. 14-33). Academic Studies Press. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters/86 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C I N E M A O f THE THAW 1953–1967 Alexander Prokhorov Ironically, the era named the Cold War by the West, Russians titled the Thaw. The Russian name of the period comes from the title of Il’ia Ehrenburg’s 1954 novel, the publication of which signaled a change in Soviet cultural politics after Stalin’s death. In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev denounced the cult of Stalin in his Secret Speech at the Twentieth Party Congress. Because literature served Soviet culture as its most authoritative form of artistic production—and the most informed of new directions the Party was adopting—changes in literature translated into new cultural policies in other art forms. Cinema was by no means the first to experience the cultural Thaw, both because film production required a greater investment of time and resources and because, despite Vladimir Lenin’s famous dictum that cinema was “the most important of all arts,” film art stood below literature in the hierarchy of Soviet arts. -

1629444096185.Pdf

AFGANTSY Also by Rodric Braithwaite Across the Moscow River (2002) Moscow 1941 (2006) AFGANTSY THE RUSSIANS IN AFGHANISTAN 1979–89 RODRIC BRAITHWAITE 1 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © Rodric Braithwaite, 2011 First published in the United States in 2011 by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Braithwaite, Rodric, 1932– Afgantsy : the Russians in Afghanistan, 1979–89 / Rodric Braithwaite. p. cm. “First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Profi le Books”—T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-983265-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Afghanistan—History—Soviet occupation, 1979–1989. 2. Soviets (People)—Afghanistan—History. 3. Russians—Afghanistan—History—20th century. 4. Soviet Union. Sovetskaia Armiia—History. 5. Soviet Union. Sovetskaia Armiia—Military life—History. 6. Soldiers—Afghanistan—History—20th century. 7. Soldiers—Soviet Union—History.