Physical Inorganic Chemistry: Principles, Methods, and Reactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photoionization Studies of Reactive Intermediates Using Synchrotron

Photoionization Studies of Reactive Intermediates using Synchrotron Radiation by John M.Dyke* School of Chemistry University of Southampton SO17 1BJ UK *e-mail: [email protected] 1 Abstract Photoionization of reactive intermediates with synchrotron radiation has reached a sufficiently advanced stage of development that it can now contribute to a number of areas in gas-phase chemistry and physics. These include the detection and spectroscopic study of reactive intermediates produced by bimolecular reactions, photolysis, pyrolysis or discharge sources, and the monitoring of reactive intermediates in situ in environments such as flames. This review summarises advances in the study of reactive intermediates with synchrotron radiation using photoelectron spectroscopy (PES) and constant-ionic-state (CIS) methods with angular resolution, and threshold photoelectron spectroscopy (TPES), taking examples mainly from the recent work of the Southampton group. The aim is to focus on the main information to be obtained from the examples considered. As future research in this area also involves photoelectron-photoion coincidence (PEPICO) and threshold photoelectron-photoion coincidence (TPEPICO) spectroscopy, these methods are also described and previous related work on reactive intermediates with these techniques is summarised. The advantages of using PEPICO and TPEPICO to complement and extend TPES and angularly resolved PES and CIS studies on reactive intermediates are highlighted. 2 1.Introduction This review is organised as follows. After an Introduction to the study of reactive intermediates by photoionization with fixed energy photon sources and synchrotron radiation, a number of Case Studies are presented of the study of reactive intermediates with synchrotron radiation using angle resolved PES and CIS, and TPE spectroscopy. -

Fundamentals of Theoretical Organic Chemistry Lecture 9

Fund. Theor. Org. Chem 1 SE Fundamentals of Theoretical Organic Chemistry Lecture 9 1 Fund. Theor. Org. Chem 2 SE 2.2.2 Electrophilic substitution The reaction which takes place between a reactant with an electronegative carbon and an electropositive reagent forming a polarized covalent bond is called electrophilic. In addition, if substitution occurs (i.e. there is a similar polarized covalent bond on the electronegative carbon, which breaks up during the reaction, so the reagent „substitutes” the „old” group or the leaving group) then this specific reaction is called electrophilic substitution. The electronegative carbon is called the reaction centre. In general, the good reactant are molecules having electronegative carbons like aromatic compounds, alkenes and other compounds containing electron-rich double bonds. These are called Lewis bases. On the contrary, good electrophilic reagents are electron poor compounds/molecule groups like acid-halides, which easily form covalent bond with an electronegative centre, thus creating a new molecule. These are often referred to as Lewis acids. According to molecular orbital (MO) theory the driving force for the electrophilic substitution (SE) is a Lewis complex formation involving the LUMO of the Lewis Acid Reagent and the HOMO of the Lewis Base Reactant. Reactant Reagent LUMO LUMO HOMO Lewis base Lewis acid Lewis complex Types of reactions: There are four types of reactions as illustrated below: 2 Fund. Theor. Org. Chem 3 SE Table. 2.2.2-1. Saturated Aromatic SE1 SE1 (Ar) SE2 SE2 (Ar) SE reaction on saturated atom: (1)Unimolecular electrophilic substitution (SE1): The reaction proceeds in two steps. After the departure of the leaving group, the negatively charged reaction intermediate will combine with the reagent. -

Bsc Chemistry

Subject Chemistry Paper No and Title 05, ORGANIC CHEMISTRY-II (REACTION MECHANISM-I) Module No and Title 15, The Neighbouring Mechanism, Neighbouring Group Participation by π and σ Bonds Module Tag CHE_P5_M15 CHEMISTRY PAPER :5, ORGANIC CHEMISTRY-II (REACTION MECHANISM-I) MODULE: 15 , The Neighbouring Mechanism, Neighbouring Group Participation by π and σ Bonds TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcomes 2. Introduction 3. NGP Participation 3.1 NGP by Heteroatom Lone Pairs 3.2 NGP by alkene 3.3 NGP by Cyclopropane, Cyclobutane or a Homoallyl group 3.4 NGP by an Aromatic Ring 4. Neighbouring Group Participation on SN2 Reactions 5. Neighbouring Group Participation on SN1 Reactions 6. Neighbouring Group and Rearrangement 7. Examples 8. Summary CHEMISTRY PAPER :5, ORGANIC CHEMISTRY-II (REACTION MECHANISM-I) MODULE: 15 , The Neighbouring Mechanism, Neighbouring Group Participation by π and σ Bonds 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you shall be able to Know about NGP reaction Learn reaction mechanism of NGP reaction Identify stereochemistry of NGP reaction Evaluate the factors affecting the NGP reaction Analyse Phenonium ion, NGP by alkene, and NGP by heteroatom. 2. Introduction The reaction centre (carbenium centre) has direct interaction with a lone pair of electrons of an atom or with the electrons of s- or p-bond present within the parent molecule but these are not in conjugation with the reaction centre. A distinction is sometimes made between n, s and p- participation. An increase in rate due to Neighbouring Group Participation (NGP) is known as "anchimeric assistance". "Synartetic acceleration" happens to be the special case of anchimeric assistance and applies to participation by electrons binding a substituent to a carbon atom in a β- position relative to the leaving group attached to the α-carbon atom. -

Golden Yearbook

Golden Yearbook Golden Yearbook Stories from graduates of the 1930s to the 1960s Foreword from the Vice-Chancellor and Principal ���������������������������������������������������������5 Message from the Chancellor ��������������������������������7 — Timeline of significant events at the University of Sydney �������������������������������������8 — The 1930s The Great Depression ������������������������������������������ 13 Graduates of the 1930s ���������������������������������������� 14 — The 1940s Australia at war ��������������������������������������������������� 21 Graduates of the 1940s ����������������������������������������22 — The 1950s Populate or perish ���������������������������������������������� 47 Graduates of the 1950s ����������������������������������������48 — The 1960s Activism and protest ������������������������������������������155 Graduates of the 1960s ���������������������������������������156 — What will tomorrow bring? ��������������������������������� 247 The University of Sydney today ���������������������������248 — Index ����������������������������������������������������������������250 Glossary ����������������������������������������������������������� 252 Produced by Marketing and Communications, the University of Sydney, December 2016. Disclaimer: The content of this publication includes edited versions of original contributions by University of Sydney alumni and relevant associated content produced by the University. The views and opinions expressed are those of the alumni contributors and do -

Linking Chemical Reaction Intermediates of the Click Reaction to Their Molecular Diffusivity

1 Linking chemical reaction intermediates of the click reaction to their molecular diffusivity Tian Huang,a Bo Li,a Huan Wang,b* and Steve Granicka,c* a Center for Soft and Living Matter, Institute for Basic Science (IBS), Ulsan 44919, South Korea b College of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, Peking University, Beijing, 100871, P. R. China c Departments of Chemistry and Physics, Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST), Ulsan 44919, South Korea Abstract Bipolar reactions have been provoked by reports of boosted diffusion during chemical and enzymatic reactions. To some, it is intuitively reasonable that relaxation to truly Brownian motion after passing an activation barrier can be slow, but to others the notion is so intuitively unphysical that they suspect the supporting experiments to be artifact. Here we study a chemical reaction according to whose mechanism some intermediate species should speed up while others slow down in predictable ways, if the boosted diffusion interpretation holds. Experimental artifacts would do not know organic chemistry mechanism, however. Accordingly, we scrutinize the absolute diffusion coefficient (D) during intermediate stages of the CuAAC reaction (copper- catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition click reaction), using proton pulsed field-gradient nuclear magnetic resonance (PFG-NMR) to discriminate between the diffusion of various reaction intermediates. For the azide reactant, its D increases during reaction, peaks at the same time as peak reaction rate, then returns to its initial value. For the alkyne reagent, its D decreases consistent with presence of the intermediate large complexes formed from copper catalyst and its ligand, except for the 2Cu-alk complex whose more rapid D may signify that this species is the 2 real reactive complex. -

Use Stable Isotopes to Investigate Microbial H2 and N2o Production

USE STABLE ISOTOPES TO INVESTIGATE MICROBIAL H2 AND N2O PRODUCTION By Hui Yang A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology - Doctor of Philosophy 2015 ABSTRACT USE STABLE ISOTOPES TO INVESTIGATE MICROBIAL H2 AND N2O PRODUCTION By Hui Yang Stable isotopes can be a useful tool in studying the basic processes involved in enzymatic catalysis. Isotope effects are quantifiable values related to the substitution of isotopes. It derives from the difference in zero-point energies. In contrast to non-catalyzed reactions, enzyme- catalyzed reactions involve multiple steps, the overall isotope effects are the sum of the isotope effects in each step. There are two major kinds of isotope effects, equilibrium isotope effects (EIEs) and kinetic isotope effects (KIEs). Each of them can provide us insights into different states in the reaction. This thesis describes several researches related to using the stable isotopes to study microbial metabolism. It is demonstrated in Chapter 2 that a method is developed for the measurement of H isotope fractionation patterns in hydrogenases. After the development of the method, a detailed study of the H2 metabolism catalyzed by different hydrogenases is presented in Chapter 3. The methods developed in hydrogenase studies were deployed in nitric oxide reductase-catalyzed N2O production studies, which is described in Chapter 4. TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..vi LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………………...vii -

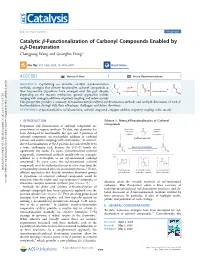

Catalytic Β-Functionalization of Carbonyl Compounds Enabled by Α

pubs.acs.org/acscatalysis Perspective Catalytic β‑Functionalization of Carbonyl Compounds Enabled by α,β-Desaturation Chengpeng Wang and Guangbin Dong* Cite This: ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 6058−6070 Read Online ACCESS Metrics & More Article Recommendations ABSTRACT: Capitalizing on versatile catalytic α,β-desaturation methods, strategies that directly functionalize carbonyl compounds at their less-reactive β-positions have emerged over the past decade. Depending on the reaction mechanism, general approaches include merging with conjugate addition, migratory coupling, and redox cascade. This perspective provides a summary of transition-metal-catalyzed α,β-desaturation methods and in-depth discussions of each β- functionalization strategy with their advantages, challenges, and future directions. KEYWORDS: β-functionalization, α,β-desaturation, carbonyl compound, conjugate addition, migratory coupling, redox cascade I. INTRODUCTION Scheme 1. Direct β-Functionalization of Carbonyl Compounds Preparation and derivatization of carbonyl compounds are cornerstones in organic synthesis. To date, rich chemistry has been developed to functionalize the ipso and α-positions of carbonyl compounds via nucleophilic addition to carbonyl carbons and enolate couplings with electrophiles.1 In contrast, direct functionalization at the β position has undoubtedly been a more challenging task, because the β-C−H bonds are significantly less acidic. To access β-functionalized carbonyl compounds, conventional methods mainly rely on conjugate addition of a nucleophile to an α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compound.2 In many cases, the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds must be synthesized in one or a few steps from the 3 Downloaded via UNIV OF CHICAGO on May 19, 2021 at 13:46:31 (UTC). corresponding saturated ones via an oxidation process. -

Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes

05 Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes Polyethylene is the most widely used plastic, making up items such as packing foam, plastic bottles, and plastic utensils (top: © Jon Larson/iStockphoto; middle: GNL Media/Digital Vision/Getty Images, Inc.; bottom: © Lakhesis/iStockphoto). Inset: A model of ethylene. KEY QUESTIONS 5.1 What Are the Characteristic Reactions of Alkenes? 5.8 How Can Alkynes Be Reduced to Alkenes and 5.2 What Is a Reaction Mechanism? Alkanes? 5.3 What Are the Mechanisms of Electrophilic Additions HOW TO to Alkenes? 5.1 How to Draw Mechanisms 5.4 What Are Carbocation Rearrangements? 5.5 What Is Hydroboration–Oxidation of an Alkene? CHEMICAL CONNECTIONS 5.6 How Can an Alkene Be Reduced to an Alkane? 5A Catalytic Cracking and the Importance of Alkenes 5.7 How Can an Acetylide Anion Be Used to Create a New Carbon–Carbon Bond? IN THIS CHAPTER, we begin our systematic study of organic reactions and their mecha- nisms. Reaction mechanisms are step-by-step descriptions of how reactions proceed and are one of the most important unifying concepts in organic chemistry. We use the reactions of alkenes as the vehicle to introduce this concept. 129 130 CHAPTER 5 Reactions of Alkenes and Alkynes 5.1 What Are the Characteristic Reactions of Alkenes? The most characteristic reaction of alkenes is addition to the carbon–carbon double bond in such a way that the pi bond is broken and, in its place, sigma bonds are formed to two new atoms or groups of atoms. Several examples of reactions at the carbon–carbon double bond are shown in Table 5.1, along with the descriptive name(s) associated with each. -

FROM the DIRECTOR: OUR NUMBERS ARE up in This Issue: Scientists Are Accustomed to Dealing with Some Pretty Big Numbers – and Some Very Small Ones Too

Australian Synchrotron Lightspeed: November 2008 FROM THE DIRECTOR: OUR NUMBERS ARE UP In this issue: Scientists are accustomed to dealing with some pretty big numbers – and some very small ones too. • From the Director • A Tribute to Hans Freeman Take an electron, for example. It weighs around • Up to Speed • Beamtime Applications 9.10938188 x 10‐31 kilograms when it’s just sitting • Synchrotron opens up around. Now take a few more, turn them into a • In science, a lot can happen in one night beam 0.06 millimetres wide, and accelerate the • Experimenting with SAXS beam to say 99.9987% of the speed of light, which • One in a thousand is 299,792,458 metres per second. Then persuade • The next generation of synchrotron PhDs your electron beam to turn enough corners to keep • Another high-performance it circulating in a synchrotron storage ring 24 hours machine • Beamline Focus a day. • Rapid Access on Trial • New Survey to Boost User That’s the amazing feat regularly performed by the Satisfaction Australia Synchrotron’s team of engineers, • A traveller’s tale accelerator physicists, operators, technicians and • Events Diary • Careers at The Australian Prof. Robert Lamb other support staff. Impressed? I certainly am. Especially when that’s combined with a beam availability of 98.3 per cent that puts us in the world’s top five synchrotrons in terms of performance. And it seems our users are impressed too. Since we opened in July 2007, over 500 users have collectively visited us more than 1000 times, and we were only running at 30 per cent capacity. -

CHEMICAL KINETICS Pt 2 Reaction Mechanisms Reaction Mechanism

Reaction Mechanism (continued) CHEMICAL The reaction KINETICS 2 C H O +→5O + 6CO 4H O Pt 2 3 4 3 2 2 2 • has many steps in the reaction mechanism. Objectives ! Be able to describe the collision and Reaction Mechanisms transition-state theories • Even though a balanced chemical equation ! Be able to use the Arrhenius theory to may give the ultimate result of a reaction, determine the activation energy for a reaction and to predict rate constants what actually happens in the reaction may take place in several steps. ! Be able to relate the molecularity of the reaction and the reaction rate and • This “pathway” the reaction takes is referred to describle the concept of the “rate- as the reaction mechanism. determining” step • The individual steps in the larger overall reaction are referred to as elementary ! Be able to describe the role of a catalyst and homogeneous, heterogeneous and reactions. enzyme catalysis Reaction Mechanisms Often Used Terms •Intermediate: formed in one step and used up in a subsequent step and so is never seen as a product. The series of steps by which a chemical reaction occurs. •Molecularity: the number of species that must collide to produce the reaction indicated by that A chemical equation does not tell us how step. reactants become products - it is a summary of the overall process. •Elementary Step: A reaction whose rate law can be written from its molecularity. •uni, bi and termolecular 1 Elementary Reactions Elementary Reactions • Consider the reaction of nitrogen dioxide with • Each step is a singular molecular event carbon monoxide. -

Introduction to Theory of Chemical Reactions

INTRODUCTION TO THEORY OF CHEMICAL REACTIONS BACKGROUND The introductory part of the organic chemistry course has three major modules: Molecular architecture (structure), molecular dynamics (conformational analysis), and molecular transformations (chemical reactions). An understanding of the first two is crucial to an understanding of the third one. The rest of the organic chemistry course will be largely spent on studying different kinds of reactions and mechanisms. A summary of key concepts follows. 1. MOLECULAR ARCHITECTURE - Basic principles of molecular structure. a) Atomic structure b) Orbitals and hybridization c) Covalent bonding d) Lewis structures and resonance forms e) Isomerism, structural and geometric isomers f) Polarity, functional groups, nomenclature systems g) Three-dimensional structures, stereochemistry, stereoisomers. 2. MOLECULAR DYNAMICS - Basic principles of molecular motion involving rotation around single bonds and no bond breakage. The focus is on conformations and their energy relationships, especially in reference to alkanes and cycloalkanes (conformational analysis). a) Steric interactions b) Torsional strain and Newman projections c) Angle strain in cycloalkanes d) Conformations of cyclohexane and terminology associated with it. 3. MOLECULAR TRANSFORMATIONS - This is the part that comprises the bulk of organic chemistry courses. It is the study of chemical reactions and the principles that rule transformations. There are three major aspects of this module. In organic chemistry I we will focus largely on the first two, and leave the study of synthetic strategy for later. a) Reaction mechanisms - Step by step accounts of how electron movement takes place when bonds are broken and formed, and the conditions that favor these processes (driving forces). An understanding of the basic concepts of thermodynamics and kinetics is important here. -

An Operando Raman, IR, and TPSR Spectroscopic Investigation of The

J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 11363–11372 11363 An Operando Raman, IR, and TPSR Spectroscopic Investigation of the Selective Oxidation of Propylene to Acrolein over a Model Supported Vanadium Oxide Monolayer Catalyst Chunli Zhao and Israel E. Wachs* Operando Molecular Spectroscopy and Catalysis Laboratory, Departments of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, 7 Asa DriVe, Sinclair Laboratory, Lehigh UniVersity, Bethlehem, PennsylVania 18015 ReceiVed: February 21, 2008; ReVised Manuscript ReceiVed: May 9, 2008 The selective oxidation of propylene to acrolein was investigated over a well-defined supported V2O5/Nb2O5 catalyst, containing a surface vanadia monolayer, with combined operando Raman/IR/MS, temperature 18 programmed surface reaction (TPSR) spectroscopy and isotopically labeled reactants ( O2 and C3D6). The dissociative chemisorption of propylene on the catalyst forms the surface allyl (H2CdCHCH2*) intermediate, the most abundant reaction intermediate. The presence of gas phase molecular O2 is required to oxidize the surface H* to H2O and prevent the hydrogenation of the surface allyl intermediate back to gaseous propylene 18 16 (Langmuir-Hinshelwood reaction mechanism). The O2 labeled studies demonstrate that only lattice Ois incorporated into the acrolein reaction product (Mars-van Krevelen reaction mechanism). This is the first time that a combined Langmuir-Hinshelwood-Mars-van Krevelen reaction mechanism has been found for a selective oxidation reaction. Comparative studies with allyl alcohol (H2CdCHCH2OH) and propylene (H2CdCHCH3) reveal that the oxygen insertion step does not precede the breaking of the surface allyl C-H bond. The deuterium labeled propylene studies show that the second C-H bond breaking of the surface allyl intermediate is the rate-determining step.