The Future of Channel 4 in a Changing Market Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing the BBC's Estate

Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Managing the BBC’s estate Report by the Comptroller and Auditor General presented to the BBC Trust Value for Money Committee, 3 December 2014 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media & Sport by Command of Her Majesty January 2015 © BBC 2015 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. BBC Trust response to the National Audit Office value for money study: Managing the BBC’s estate This year the Executive has developed a BBC Trust response new strategy which has been reviewed by As governing body of the BBC, the Trust is the Trust. In the short term, the Executive responsible for ensuring that the licence fee is focused on delivering the disposal of is spent efficiently and effectively. One of the Media Village in west London and associated ways we do this is by receiving and acting staff moves including plans to relocate staff upon value for money reports from the NAO. to surplus space in Birmingham, Salford, This report, which has focused on the BBC’s Bristol and Caversham. This disposal will management of its estate, has found that the reduce vacant space to just 2.6 per cent and BBC has made good progress in rationalising significantly reduce costs. -

PSB Report Definitions

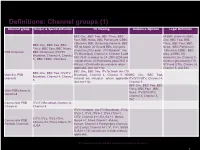

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

Subsidies and Funding from Some of the Largest UK Industries, She Also Signalled a Break with the Idea of the Economic State

James Webber All Change? UK State Aid after Brexit What Law? Whose Courts? Copy Proof POLITEIA A FORUM FOR SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC THINKING POLITEIA A Forum for Social and Economic Thinking Politeia commissions and publishes discussions by specialists about social and economic ideas and policies. It aims to encourage public discussion on the relationship between the state and the people. Its aim is not to influence people to support any given political party, candidates for election, or position in a referendum, but to inform public discussion of policy. The forum is independently funded, and the publications do not express a corporate opinion, but the views of their individual authors. www.politeia.co.uk All Change? UK State Aid after Brexit What Law? Whose Courts? James Webber POLITEIA 2020 First published in 2020 by Politeia 14a Eccleston Street London SW1W 9LT Tel: 0207 799 5034 Email: [email protected] Website: www.politeia.co.uk © Politeia 2020 ISBN 978-1-9993662-9-2 Cover design by John Marenbon Politeia gratefully acknowledges support for this publication from The Foundation for Social and Economic Thinking (FSET) Printed in the United Kingdom by: Millnet Limited 6-7 Princes Court 11 Wapping Lane London E1W 2DA Foreword State Aid, the EU and the UK Economy Different Systems, Different Rules Sheila Lawlor, Director of Politeia The battle and its background.1 Very shortly the next battle with the EU will begin over an unlikely battleground: what rules should govern UK State aid and what are their implications for a trade deal with the bloc? For the UK, a country that, more than most others, has championed free trade, unfettered and competitive markets and an economy under the rule of law, the subject seems uncontentious. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Jo Swinson: the New Liberal Democrat Leader

Jo Swinson: the new Liberal Democrat Leader 22 July 2019 Who is Jo Swinson? Jo Swinson was born in 1980, growing up and going to school in East Dunbartonshire, which she now represents in Parliament. Her mother was a primary school teacher while her father worked in economic development. She cites her earliest political experience as signing petitions against animal testing in the Body Shop. A Liberal Democrat supporter since she was at school, Jo joined the Liberal Democrats aged 17, while studying Management at the LSE. During her time at university, she worked as a Research Assistant for the Employers’ Forum on Disability. After graduating, Swinson moved to Hull, working as Viking FM’s Marketing & PR Manager. Aged 21, she stood against John Prescott at the 2001 general election in Hull East. Relocating back to Scotland, she worked as Marketing Manager for SpaceandPeople Plc and then as Communications Officer for the UK Public Health Association prior to her election as an MP. In 2011, she married Duncan Hames, who was the Liberal Democrat MP for Chippenham from 2010 to 2015, and is now an anti-corruption campaigner. The couple have two sons. What is Jo Swinson’s political background? Swinson was successfully elected to Parliament in 2005, winning East Dunbartonshire from Labour. In the Commons, she became a Lib Dem whip and spokesperson for culture, media and sport, before being promoted to Shadow Secretary of State for Scotland in 2006. Swinson gained additional responsibility in 2007 becoming Shadow Women and Equality Minister. She returned to the backbenches later that year, before becoming Shadow Minister for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs in 2008, retaining this role until the 2010 election. -

Statement: Ofcom's Plan of Work 2021/22

Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 Making communications work for everyone Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 – Welsh translation STATEMENT: Publication Date: 26 March 2021 Contents Section 1. Chief Executive’s foreword 1 2. Overview 3 3. Our goals and priorities for 2021/22 9 4. Delivering good outcomes for consumers across the UK 31 Annex A1. What we do 37 A2. Project work for 2021/2022 39 Plan of Work 2021/22 1. Chief Executive’s foreword Ofcom is the UK’s communications regulator, with a mission to make communications work for everyone. We serve the interests of consumers and businesses across the UK’s nations and regions, through our work in mobile and fixed telecoms, broadcasting, spectrum, post and online services. Over the past year we have learned that being connected is everything. High-quality, reliable communications services have never mattered more to people’s lives. But as consumers shift their habits increasingly online, our communications sectors are transforming fast. It is an exciting moment for our industries and for Ofcom as a regulator - it requires long-term focus alongside speed and agility in response to change. Against this backdrop our statement sets out our detailed goals for the coming financial year, and how we plan to achieve them. On telecoms, Ofcom has just confirmed a new long-term framework for investment in gigabit- capable fixed networks. In the coming year, we will shift our focus to support delivery against this programme, alongside investment and innovation in 5G and new mobile infrastructure. Following legislation in Parliament, we will put in place new rules to hold operators to account for the security and resilience of their networks. -

ITV Plc Final Results 2007

ITV plc Final Results 2007 5th March 2008 1 Introduction Michael Grade Executive Chairman 2 Agenda Introduction Financial and operating review Current trading and strategy update 3 Overview 2007 financial results Total revenue £2,082m (2006: £2,181m) Operating EBITA £311m (2006: £375m) Impacted by legacy issues and digital investment 2007 operational and strategic progress ITV viewing increased year-on-year for first time in over a decade ITV NAR stabilised at £1,489m (2006: £1,494m) Strengthened management team appointed Strategic plan and targets announced 2008 current trading ITV outperforming market in revenues and ratings Î Turnaround plan on track 4 Board and management changes Executive Chairman term extended to four years and end of 2010 John Cresswell becomes dedicated COO, with new FD to be appointed Dawn Airey and Rupert Howell join plc Board Peter Fincham to join as ITV Director of Television 5 Financial and operating review John Cresswell Chief Operating Officer 6 Final Results 12 months to 31st Dec - £m 2007 2006 Change Published Published % Revenue 2,082 2,181 (5) Operating EBITA 311 375 (17) Amortisation Normal (56) (56) CSA Impairment (28) (20) Exceptional items inc gains on sales (9) 4 Associates, JVs and investment income 3 11 Profit before interest and tax 221 314 (30) Interest (33) (26) 27 Profit before tax 188 288 (35) 7 Final Results 12 months to 31st Dec - £m 2007 2006 Change Published Published % Profit before tax 188 288 (35) Tax (50) (66) (24) Profit after tax 138 222 (38) Minority interests (1) -

HD Digital Box GFSAT200HD/A Instruction Manual Welcome to Your

HD Digital Box GFSAT200HD/A Instruction Manual Welcome to your new freesat+ HD digital TV recorder Now you can pause, rewind and record both HD and SD television, and so much more Goodmans GFSAT200HD-A_IB_Rev2_120710.indd 1 12/07/2010 14:11:18 Welcome Thank you for choosing this Goodmans freesat HD Digital Box. Not only can it receive over 140 subscription free channels, but if you have a broadband service with a minimum speed of 1Mb you can access IP TV services, which you can watch back at a time to suit you. It’s really simple to use; it’s all done using the clear, easy to understand on screen menus which are operated from the remote control. It even has a reminder function so that you won’t miss your favourite programmes. For a one off payment, you can buy a digital A digital box lets you access digital channels box, satellite dish and installation giving you that are broadcast in the UK. It uses a digital over 140 channels covering the best of TV signal, received through your satellite dish and more. and lets you watch it through your existing television. This product is capable of receiving and This product has a HDMI connector so that decoding Dolby Digital Plus. you can watch high definition TV via a HDMI lead when connected to a HD Ready TV. Manufactured under license from Dolby HDMI, the HDMI logo and High-Definition Laboratories. Dolby and the double-D symbol Multimedia Interface are trademarks or are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. -

Media: Industry Overview

MEDIA: INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 7 This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: uk.practicallaw.com/w-022-5168 Get more information on Practical Law and request a free trial at: www.practicallaw.com This note provides an overview of the sub-sectors within the UK media industry. RESOURCE INFORMATION by Lisbeth Savill, Clare Hardwick, Rachael Astin and Emma Pianta, Latham & Watkins, LLP RESOURCE ID w-022-5168 CONTENTS RESOURCE TYPE • Scope of this note • Publishing and the press Sector note • Film • Podcasts and digital audiobooks CREATED ON – Production • Advertising 13 November 2019 – Financing and distribution • Recorded music JURISDICTION • Television • Video games United Kingdom – Production • Radio – Linear and catch-up television • Social media – Video on-demand and video-sharing services • Media sector litigation SCOPE OF THIS NOTE This note provides an overview of the sub-sectors within the UK media industry. Although the note is broken down by sub-sector, in practice, many of these areas overlap in the converged media landscape. For more detailed notes on media industry sub-sectors, see: • Sector note, Recorded music industry overview. • Sector note, TV and fi lm industry overview. • Practice note, Video games industry overview. FILM Production Total UK spend on feature fi lms in 2017 was £2 billion (up 17% on 2016) (see British Film Institute (BFI): Statistical Yearbook 2018). Film production activity in the UK is driven by various factors, including infrastructure, facilities, availability of skills and creative talent and the incentive of fi lm tax relief (for further information, see Practice note, Film tax relief). UK-produced fi lms can broadly be sub-divided into independent fi lms, UK studio-backed fi lms and non-UK fi lms made in the UK. -

BBC Trust’S Review of BBC Services for Younger Audiences

Channel 4 submission to the BBC Trust’s review of BBC services for younger audiences 1. Channel 4 welcomes the opportunity to provide its views to the BBC Trust’s review of BBC services for younger audiences. Channel 4 is a publicly-owned, commercially-funded public service broadcaster. Its core public service channel, Channel 4, is a free-to-air service funded predominantly by advertising. Unlike the other commercially-funded public service broadcasters, Channel 4 is not shareholder owned: commercial revenue is only a means to delivering Channel 4’s public purpose end and any surplus revenues are reinvested in the delivery of its public service remit. 2. In recent years, Channel 4 has broadened its portfolio to offer a range of digital services, including the free-to-air, commercially-funded digital television channels Channel 4+1, E4, E4+1, Film4, More4 and 4Music. Channel 4 also offers a video on demand service, 4oD, and it is expanding its range of services at channel4.com. In addition, Channel 4 offers a range of online education projects for 14 to 19 year olds and has launched an innovation pilot fund, 4iP, which seeks to stimulate whole new digital media services across a range of areas, including video games, the arts, democracy and sport. 3. These innovations have allowed Channel 4 to stay in touch with audiences— especially younger viewers—who are rapidly migrating to digital media. Ever since its launch in 1982, Channel 4’s brand has resonated particularly strongly with teenagers and younger adults, and the organisation speaks with an authenticity of voice which is not easily replicated by other public institutions. -

Digital Television Transmitters: Pre-Switchover Network

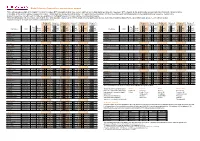

Digital Television Transmitters: pre-switchover network This leaflet provides details of the Digital Terrestrial Television (DTT) transmitters which have not yet switched over to fully-digital operation (the 'low power' DTT network). Detailed information on post-switchover transmitter characteristics is available on the Ofcom website at www.ofcom.org.uk. Transmitters are grouped according to the ITV1 region that they broadcast, which will determine each transmitter's place in the digital switchover sequence. Details of the programme services carried in each multiplex are available on the Digital Television Group's website, www.dtg.org.uk/retailer. While this information is believed to be correct at the time of preparation, changes to the DTT network will occur, particularly as more transmitters switch to digital. For the latest information, please see the Ofcom website, www.ofcom.org.uk, or Digital UK's website, www.digitaluk.co.uk. Multiplex 1 Multiplex 2 Multiplex A Multiplex B Multiplex C Multiplex D Multiplex 1 Multiplex 2 Multiplex A Multiplex B Multiplex C Multiplex D BBC Digital 3&4 SDN BBC Arqiva Arqiva BBC Digital 3&4 SDN BBC Arqiva Arqiva Avg. Avg. Aerial ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP Aerial ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP Site Name NGR Aerial Site Name NGR Aerial Group (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) Group (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Height Offset Height Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Anglia Tyne Tees -

FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK Inc NI) Incorporating Planned Local TV and Temporary HD Muxes

As at 07 December 2020 FREEVIEW DTT Multiplexes (UK inc NI) incorporating planned Local TV and Temporary HD muxes 3PSB: Available from all transmitters (*primary and relay) 3 COM: From *80 primary transmitters only Temp HD - 25 Transmiters BBC A (PSB1) BBC A (PSB1) continued BBC B (PSB3) HD SDN (COM4) ARQIVA A (COM5) ARQIVA B (COM6) ARQIVA C (COM7) HD ARQIVA D (COM8) HD LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN LCN 1 BBC ONE 65 TBN UK 12 QUEST 11 Sky Arts 22 Ideal World 64 Free Sports BBC RADIO: 1 BBC ONE NI Cambridge, Lincolnshire, 74 Shopping Quarter 13 E4 (Wales only) 17 Really 23 Dave ja vu 70 Quest Red+1 722 Merseyside, Oxford, 1 BBC ONE Scot Solent, Somerset, Surrey, 101 BBC 1 Scot HD 16 QVC 19 Dave 26 Yesterday 83 NOW XMAS Tyne Tees, WM 1 BBC ONE Wales 101 BBC 1 Wales HD 20 Drama 30 4Music 33 Sony Movies 86 More4+1 2 BBC TWO 101 BBC ONE HD 21 5 USA 35 Pick 36 QVC Beauty 88 TogetherTV+1 (00:00-21:00) 2 BBC TWO NI BBC RADIO: 101 BBC ONE NI HD 27 ITVBe 39 Quest Red 37 QVC Style 93 PBS America+1 726 BBC Solent Dorset 2 BBC TWO Wales BBC Stoke 102 BBC 2 Wales HD 28 ITV2 +1 42 Food Network 38 DMAX 96 Forces TV 7 BBC ALBA (Scot only) 102 BBC TWO HD 31 5 STAR 44 Gems TV 40 CBS Justice 106 BBC FOUR HD 9 BBC FOUR 102 BBC TWO NI HD 32 Paramount Network 46 Film4+1 43 HGTV 107 BBC NEWS HD Sony Movies Action 9 BBC SCOTLAND (Scot only) BBC RADIO: 103 ITV HD 41 47 Challenge 67 CBS Drama 111 QVC HD (exc Wales) 734 Essex, Northampton, CLOSED 24 BBC FOUR (Scot only) Sheffield, 103 ITV Wales HD 45 Channel 5+1 48 4Seven 71 Jewellery Maker 112 QVC Beauty HD 201 CBBC