Ukrainian Canadians, 100 Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ukrainian Language in Canada: from Prosperity to Extinction?

Ukrainian language in Canada: From prosperity to extinction? Khrystyna Hudyma University of Saskatchewan In this paper I want to explore in what way and due to what factors the Ukrainian language in Canada evolved from being a mother tongue for one of the biggest country’s ethnic groups to just an ethnic language hardly spoken by younger generations. Ukrainian was brought to the country by peasant settlers from Western Ukraine at the end of the 19th century; therefore, it is one of the oldest heritage languages in Canada. Three subsequent waves of Ukrainian immigration supplied language retention; however had their own language-related peculiarities. Initially, the Ukrainian language in Canada differed from standard Ukrainian, with the pace of time and under influence of the English language they diverged even more. Profound changes on phonetic, lexical and grammatical levels allow some scholars to consider Canadian Ukrainian an established dialect of standard Ukrainian. Once one of the best maintained mother tongues in Canada, today Ukrainian experiences a significant drop in number of native speakers and use at home, as well as faces a persistent failure of transmission to the next generation. Although, numerous efforts are made to maintain Ukrainian in Canada, i.e. bilingual schools, summer camps, university courses, the young generation of Ukrainian Canadians learn it as a foreign language and limit its use to family and school settings. Such tendency fosters language shift and puts Canadian Ukrainian on the brink of extinction in the nearest future. 1 Introduction The first records of immigrants arriving from the territory of modern Ukraine to Canada go back to 1892, and thus, have more than a century of history. -

Individual and Collective Remembering

Ukrainian Ostarbeiters in Canada: Individual and Collective Remembering A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Maria Melenchuk © Copyright, Maria Melenchuk, August 2012. All rights reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Masters of Arts degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that the permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis works or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any coping or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 Canada or Dean College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan 107 Administrative Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A2 Canada i Abstract When the Second World War came to an end, some 150 thousand Ukrainian Ostarbeiters (civilian labourers who were forcibly recruited to work for the Nazi economy during the war) refused to return from Germany to the Soviet-dominated Ukraine. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1972

UNA DELIVERS MONEY FOR FLOOD VICTIMS THREE MORE UKRAINIANS COMMUNITIES OBSERVE CAPTIVE NATIONS WEEK JERSEY CITY, N.J.—The SENTENCED TO LABOR CAMPS Supreme Executive Commit MOSCOW, July 18, Reuter nylo Shumuk, was sentenced +*r*'\ JERSEY CITY, N.J. — In tee of the Ukrainian Nation News Service — Three Uk-I to ten years in a labor camp Captive Nations Week conjunction with President al Association delivered rainians have been given la and five in exile. Exact char Nixon's proclamation of Cap checks for the amount of bor camp sentences in separ-1 ges against him were not tive Nations Week, Ukrain A PROCLAMATION BY THE PRESIDENT OF ians and members of other $10,400 to the UNA Wilkes- ate trials linked with a major known. THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Barre and Elmira districts to security police drive against The trials, held in the Kiev ethnic groups took part in aid the Ukrainian victims of nationalists and their home region this month and last, !| The cause of human rights and personal dignity re- \\ marches, religious services the recent floods in these republics, usually reliable followed a report in the Chro !| mains a universal aspiration. Yet, In much of the world, !| and other programs across the areas. sources said today. nicle of Current Events, an ;|the struggle for freedom and independence continues, j! nation in annual observances Supreme President Joseph Two of the men were found underground journal, that I jit is appropriate, therefore, that we who value our own;; dedicated to. suppressed peo Leeawyer and assistant to the guilty of anti-Soviet agitation security police had arrested !; precious heritage should manifest our sympathy and un-i; ples in the world. -

Multiculturalism and Identity in Canada

MULTICULTURALISM AND IDENTITY IN CANADA: A CASE-STUDY OF UKRAINIAN-CANADIANS A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Eric Woods © Copyright Eric Woods, April 2006. All rights reserved PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Librairies of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7N 5A5 i ABSTRACT The thesis provides a political analysis of a position paper on government programming recently adopted by the Ukrainian Canadian Congress (UCC) – a national ethno-cultural organisation that ostensibly represents over one million Canadians of Ukrainian heritage and a historically important player in the development of multiculturalism in Canada. -

Ukrainian Immigrants Arrive on the Canadian Prairies

Ukrainian immigrants arrive on #1 the Canadian prairies Letter written on May 15, 1897 by W. F. McCreary, the Commissioner Conditions for early of Immigration in Winnipeg to James Smart, the Deputy Minister of the Ukrainian immigrants Interior. Comments in brackets are not part of the original document. They have been added to assist the reader with difficult words. Office of the Commissioner of Immigration Winnipeg, Manitoba May 15, 1897 Sir, As I have previously written you, there are quite a large number of these Galicians who are still remaining in this Shed [Immigra- tion sheds] and have absolutely no money …. Most of these are what is known in their country as Bukownians, and are somewhat different from the regular Galicians; their chief difference, however, being in their religious persuasion. They do not affiliate, and, in fact, are detested by the Galicians; they are a lower class, more destitute [poor] and more awkward to handle. Now, I cannot see what these people will do They were told that the Crown Princess without a single dollar if they should be of Austria was in Montreal, and that she placed on land; it would be a case of as- would see that they got free lands with sistance from the Government for some time, houses on them, cattle and so forth, and and the expense would run up very high. that all they required to do was to tele- graph to her in Montreal in case their I secured a contract of 1000 cords [stacks] requests were not granted. These and other of wood to be cut about fifteen miles from similar stories have been so impressed the City, at 45 cents per cord, and they on their minds that they now seem very to board themselves. -

White Or Foreign? Differentiating Perceptions of the Racialization of National Identity in Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 6-2-2020 White or Foreign? Differentiating Perceptions of the Racialization of National Identity in Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand Lucy Hu University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Comparative Politics Commons Recommended Citation Hu, Lucy, "White or Foreign? Differentiating Perceptions of the Racialization of National Identity in Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand" 02 June 2020. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/237. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/237 For more information, please contact [email protected]. White or Foreign? Differentiating Perceptions of the Racialization of National Identity in Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand Abstract Past literature has established that often in a white-majority society, a national label is associated with the white population more than people of other ethnic origins. Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand share many historical and institutional similarities, making them valuable comparative cases. While scholars have researched national identity to varying degrees in these countries, the gap remains in comparative analysis of perceptions of national identity. This thesis first analyzes comparative public opinion data to establish differences in the degree to which national identity is racially-exclusive in the case countries. Second, it compares historical immigration policy, multiculturalism policy and programs, and ethnic activism in each country to understand what causes varying levels of racialization. -

Ethnic Spatial Segmentation in Immigrant Destinations—Edmonton and Calgary

Int. Migration & Integration https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-018-0604-y Ethnic Spatial Segmentation in Immigrant Destinations—Edmonton and Calgary Sandeep Agrawal 1 & Nicole Kurtz1 # Springer Nature B.V. 2018 Abstract Immigrant destinations other than Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver are often overlooked in Canadian immigration and settlement debates and discussions. Between 2011 and 2016, such destinations received over 40% of all immigrants arriving in Canada. This study endeavors to systematize the classification of commu- nities where immigrants are destined to settle. It also explores the issue of spatial segmentation in two such places in Alberta—Edmonton and Calgary. In both metro- politan areas, ethnic spatial segmentation exists, but not at the same scale as in a large metropolis like Toronto. Both metropolitan areas still have a substantial population of established white Canadians who identify as Germans or Ukrainians, although most of them reside in rural parts of these two areas. However, the rest of the urban landscapes is a mix of the white Canadians and recently arrived visible minorities. Keywords Spatialsegmentation.Ethnicenclaves.Second-tiercity.Edmonton .Calgary Introduction Immigrant destinations outside of Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver (TMV) received over 40% of all immigrants who arrived in Canada between 2011 and 2016. In the last decade or so, Edmonton and Calgary have been among the top such destinations. However, while several studies have looked at large cities (such as TMV), fewer studies exist on medium-size cities like Edmonton and Calgary—even though these cities are considered large within the Alberta context. Studies on non-TMV immigrants’ settle- ments (also termed as second- or third-tier destinations) have largely focused on the availability of affordable housing (Teixeira 2009), the municipal role in immigrant dispersal and regionalization (Walton-Roberts 2005, 2007), quality of life of * Sandeep Agrawal [email protected] 1 University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada Agrawal S., Kurtz N. -

Mapping the Social Participation of South Asians and Mainstream/Dominant Canadians: a Comparative Study

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2013-10-18 Mapping the Social Participation of South Asians and Mainstream/Dominant Canadians: A Comparative Study Ranu, Koyel Ranu, K. (2013). Mapping the Social Participation of South Asians and Mainstream/Dominant Canadians: A Comparative Study (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26831 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1154 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Mapping the Social Participation of South Asians and Mainstream/Dominant Canadians: A Comparative Study by Koyel Ranu A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY CALGARY, ALBERTA OCTOBER, 2013 © Koyel Ranu 2013 Abstract This research studies how actively South Asian immigrants in Canada are engaged in the social participation process and their underlying motivations. Social participation of South Asians in Canada is compared with Canadians of British lineage and East Indians in their homeland (India), and reasons behind any differences in levels of social participation are examined. In this endeavour, the circular relationship between social participation and social capital is investigated and the formulations of the concepts are problematized and critiqued. -

Racism Timeline: Events

The CARED Collective Racism Timeline: Events Canada has 6.8 million foreign-born residents (20.6% of the population). A ten-year-old policy resurfaces which says that Sikh visa applicants with last names of “Singh” or “Kaur” do not qualify for immigration to Canada; officials say there are too many of them and that it is difficult to maintain the database. They do not seem to have similar problems with common Western surnames such as “Smith” or “Brown.” Chinese people begin to immigrate to Canada to escape rural poverty and political upheaval caused by the First Opium War and the Hakka led T’ai P’ing Rebellion. South Africa sends representatives to Canada to study the Canadian system for reserves for Indigenous people. Their findings were helpful in establishing the apartheid system in South Africa – that is, segregating their own Indigenous people into “townships” or “homelands.” 1 The CARED Collective 3,000 Black Loyalists who had been emancipated in the American colonies, in exchange for supporting the British, enter Canada as “free” persons. They encountered blatant discrimination and were exploited as a source of free labour. They were promised 100-acre lots (like White Loyalists) but either received no land at all or were given barren 1 acre lots on the fringe of White Loyalist townships. About 1,200 of the Black Loyalists resettled in Sierra Leone to escape these intolerable conditions. Shawn Brant, a member of the Mohawk Nation is denied bail for the second time on charges related to the closure of the CN main line, a provincial highway, and the 401. -

Ukrainian Immigration and Settlement Patterns in Canada Beginnings Of

Ukrainian Immigration and Settlement Patterns in Canada Beginnings of Emigration from Ukraine Before overseas emigration captured the imagination of the Ukrainians, their experience with largescale migration was limited. In Russian Ukraine, the only significant migration began in the late 19th century when the government encouraged colonization of newly annexed territories in Central Asia and the Far East. The overseas emigration from the Russian Empire was largely limited to the persecuted Jews. In AustroHungary, seasonal migration, in search of work beyond its borders, was widely practiced. The Ukrainian inhabitants of Transcarpathia were the first to leave for the United States in the 1870s, destined for the coal mines of Pennsylvania. The first group of Ukrainians from Galicia, lured by the rumours of wellpaying jobs, followed in 1879. These early immigrants were by and large experienced migrant labourers whose original intention was to return home, after making fortunes in America. Attracted by exaggerated offers of free lands and free passage, between 24,000 and 30,000 impoverished peasants from Galicia left for Brazil in the 1880s. Their initial illusions were quickly and painfully shattered by the radically different climatic conditions, tropical diseases, hard contract labour on plantations and a corrupt immigration bureaucracy. Anguished letters home caused concern among the intelligentsia and prompted Joseph Oleskiw, a professor of agriculture in Lviv, to investigate alternative destinations for resettlement. In September 1891, two peasants from the village of Nebyliv, Wasyl Eleniak and Ivan Pillipiw, became the first documented Ukrainian settlers in Canada when they began homesteading in Alberta. Their news that plenty of virtually free land was available for homesteading caused a sensation at home. -

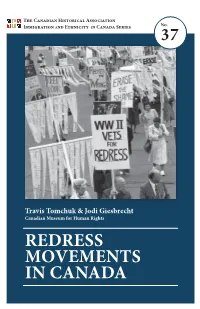

REDRESS MOVEMENTS in CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo

The Canadian Historical Association No. Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series 37 Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures on behalf of all levels of government in Canada in order to acknowledge the historic wrongs suffered by diverse ethnic and immigrant groups. -

Advocacy by Canada's Ukrainian Diaspora in the Context of Regime

Central and Eastern European Migration Review Received: 9 July 2019, Accepted: 14 February 2020 Published online: 6 March 2020 Vol. 9, No. 2, 2020, pp. 35–51 doi: 10.17467/ceemr.2020.01 Helping the Homeland in Troubled Times: Advocacy by Canada’s Ukrainian Diaspora in the Context of Regime Change and War in Ukraine Klavdia Tatar* This paper analyses diaspora advocacy on behalf of Ukraine as practiced by a particular diaspora group, Ukrainian Canadians, in a period of high volatility in Ukraine: from the EuroMaidan protests to the Russian invasion of Eastern Ukraine. This article seeks to add to the debate on how conflict in the homeland affects a diaspora’s mobilisation and advocacy patterns. I argue that the Maidan and the war played an important role not only in mobilising and uniting disparate diaspora communities in Canada but also in producing new advocacy strategies and increasing the diaspora’s political visibility. The paper begins by mapping out the diaspora players engaged in pro-Ukraine advocacy in Canada. It is followed by an analysis of the diaspora’s patterns of mobilisation and a discussion of actual advocacy outcomes. The second part of the paper inves- tigates successes in the diaspora’s post-Maidan communication strategies. Evidence indicates that the dias- pora’s advocacy from Canada not only brought much-needed assistance to Ukraine but also contributed to strengthening its own image as an influential player. Finally, the paper suggests that political events in the homeland can serve as a mobilising factor but produce effective advocacy only when a diaspora has already achieved a high level of organisational capacity and created well-established channels via which to lobby for homeland interests.