MP3 Complete by Guy Hart-Davis and Rhonda Holmes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographies of Computer Scientists

1 Charles Babbage 26 December 1791 (London, UK) – 18 October 1871 (London, UK) Life and Times Charles Babbage was born into a wealthy family, and started his mathematics education very early. By . 1811, when he went to Trinity College, Cambridge, he found that he knew more mathematics then his professors. He moved to Peterhouse, Cambridge from where he graduated in 1814. However, rather than come second to his friend Herschel in the final examinations, Babbage decided not to compete for an honors degree. In 1815 he co-founded the Analytical Society dedicated to studying continental reforms of Newton's formulation of “The Calculus”. He was one of the founders of the Astronomical Society in 1820. In 1821 Babbage started work on his Difference Engine designed to accurately compile tables. Babbage received government funding to construct an actual machine, but they stopped the funding in 1832 when it became clear that its construction was running well over-budget George Schuetz completed a machine based on the design of the Difference Engine in 1854. On completing the design of the Difference Engine, Babbage started work on the Analytical Engine capable of more general symbolic manipulations. The design of the Analytical Engine was complete in 1856, but a complete machine would not be constructed for over a century. Babbage's interests were wide. It is claimed that he invented cow-catchers for railway engines, the uniform postal rate, a means of recognizing lighthouses. He was also interested in locks and ciphers. He was politically active and wrote many treatises. One of the more famous proposed the banning of street musicians. -

Convention Program

AAEESS 112244tthh CCOONNVVEENNTTIIOONN PPRROOGGRRAAMM May 17 – 20, 2008 RAI International Exhibition & Congress Centre, Amsterdam The AES has launched a new opportunity to recognize 1University of Salford, Salford, Greater student members who author technical papers. The Stu- Manchester, UK dent Paper Award Competition is based on the preprint 2ICW, Ltd., Wrexham, Wales, UK manuscripts accepted for the AES convention. Forty-two student-authored papers were nominated. This paper gives an account of work carried out The excellent quality of the submissions has made the to assess the effects of metallized film selection process both challenging and exhilarating. polypropylene crossover capacitors on key sonic The award-winning student paper will be honored dur- attributes of reproduced sound. The capacitors ing the convention, and the student-authored manuscript under investigation were found to be mechani- will be published in a timely manner in the Journal of the cally resonant within the audio frequency band, Audio Engineering Society. and results obtained from subjective listening Nominees for the Student Paper Award were required tests have shown this to have a measurable to meet the following qualifications: effect on audio delivery. The listening test methodology employed in this study evolved (a) The paper was accepted for presentation at the from initial ABX type tests with set program AES 124th Convention. material to the final A/B tests where trained test (b) The first author was a student when the work was subjects used program material that they were conducted and the manuscript prepared. familiar with. The main findings were that (c) The student author’s affiliation listed in the manu- capacitors used in crossover circuitry can exhibit script is an accredited educational institution. -

4. MPEG Layer-3 Audio Encoding

MPEG Layer-3 An introduction to MPEG Layer-3 K. Brandenburg and H. Popp Fraunhofer Institut für Integrierte Schaltungen (IIS) MPEG Layer-3, otherwise known as MP3, has generated a phenomenal interest among Internet users, or at least among those who want to download highly-compressed digital audio files at near-CD quality. This article provides an introduction to the work of the MPEG group which was, and still is, responsible for bringing this open (i.e. non-proprietary) compression standard to the forefront of Internet audio downloads. 1. Introduction The audio coding scheme MPEG Layer-3 will soon celebrate its 10th birthday, having been standardized in 1991. In its first years, the scheme was mainly used within DSP- based codecs for studio applications, allowing professionals to use ISDN phone lines as cost-effective music links with high sound quality. In 1995, MPEG Layer-3 was selected as the audio format for the digital satellite broadcasting system developed by World- Space. This was its first step into the mass market. Its second step soon followed, due to the use of the Internet for the electronic distribution of music. Here, the proliferation of audio material – coded with MPEG Layer-3 (aka MP3) – has shown an exponential growth since 1995. By early 1999, “.mp3” had become the most popular search term on the Web (according to http://www.searchterms.com). In 1998, the “MPMAN” (by Saehan Information Systems, South Korea) was the first portable MP3 player, pioneering the road for numerous other manufacturers of consumer electronics. “MP3” has been featured in many articles, mostly on the business pages of newspapers and periodicals, due to its enormous impact on the recording industry. -

International Organisation for Standardisation Organisation Internationale De Normalisation Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc29/Wg11 Coding of Moving Pictures and Audio

INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATION FOR STANDARDISATION ORGANISATION INTERNATIONALE DE NORMALISATION ISO/IEC JTC1/SC29/WG11 CODING OF MOVING PICTURES AND AUDIO ISO/IEC JTC1/SC29/WG11 MPEG98/N2425 Atlantic City - October 1998 Source: Audio and Test subgroup Status: Approved Title: MPEG-4 Audio verification test results: Audio on Internet Authors: Eric Scheirer, Sang-Wook Kim, Martin Dietz Table of Contents 1. Introduction.....................................................................................................................................2 2. Test motivation................................................................................................................................2 3. Codecs under Test ...........................................................................................................................3 4. Test Material...................................................................................................................................5 5. Test methodology ............................................................................................................................7 6. Test stimuli .....................................................................................................................................7 7. Test sessions ...................................................................................................................................8 8. Data Analysis..................................................................................................................................8 -

What Is Ogg Vorbis?

Ogg Vorbis Audio Compression Format Norat Rossello Castilla 5/18/2005 Ogg Vorbis 1 What is Ogg Vorbis? z Audio compression format z Comparable to MP3, VQF, AAC, TwinVQ z Free, open and unpatented z Broadcasting, radio station and television by internet ( = Streaming) 5/18/2005 Ogg Vorbis 2 1 About the name… z Ogg = name of Xiph.org container format for audio, video and metadata z Vorbis = name of specific audio compression scheme designed to be contained in Ogg FOR MORE INFO... https://www.xiph.org 5/18/2005 Ogg Vorbis 3 Some comercial characteristics z The official mime type was approved in February 2003 z Posible to encode all music or audio content in Vorbis z Designed to not be proprietary or patented audio format z Patent and licensed-free z Specification in public domain 5/18/2005 Ogg Vorbis 4 2 Audio Compression z Two classes of compression algorithms: - Lossless - Lossy FOR MORE INFO... http://www.firstpr.com.au/audiocomp 5/18/2005 Ogg Vorbis 5 Lossless algorithms z Produce compressed data that can be decoded to output that is identical to the original. z Zip, FLAC for audio 5/18/2005 Ogg Vorbis 6 3 Lossy algorithms z Discard data in order to compress it better than would normally be possible z VORBIS, MP3, JPEG z Throw away parts of the audio waveform that are irrelevant. 5/18/2005 Ogg Vorbis 7 Ogg Vorbis - Compression Factors z Vorbis is an audio codec that generates 16 bit samples at 16KHz to 48KHz, providing variable bit rates from 16 to 128 Kbps per channel FOR MORE INFO.. -

User Manual Contents

Register your product and get support at 8209 www.philips.com/welcome 48PFS8209 48PFS8209 55PFS8209 55PFS8209 User Manual Contents 6.7 Batteries 28 1 TV Tour 4 6.8 Cleaning 28 1.1 Android TV 4 1.2 Apps 4 7 Gesture Control 30 1.3 Movies and Missed Shows 4 7.1 About Gesture Control 30 1.4 Social Networks 4 7.2 Camera 30 1.5 Pause TV and Recordings 4 7.3 Hand Gestures 30 1.6 Gaming 4 7.4 Gesture Overview 30 1.7 Skype 4 7.5 Tips 30 1.8 3D 5 1.9 Smartphones and Tablets 5 8 Home Menu 32 8.1 Open the Home Menu 32 2 Setting Up 6 8.2 Overview 32 2.1 Read Safety 6 8.3 Notifications 32 2.2 TV Stand and Wall Mounting 6 8.4 Search 32 2.3 Tips on Placement 6 2.4 Power Cable 6 9 Now on TV 33 2.5 Antenna Cable 6 9.1 About Now on TV 33 2.6 Satellite Dish 7 9.2 What You Need 33 9.3 Using Now on TV 33 3 Network 8 3.1 Connect to Network 8 10 Apps 34 3.2 Network Settings 9 10.1 About Apps 34 3.3 Network Devices 10 10.2 Install an App 34 3.4 File Sharing 10 10.3 Start an App 34 10.4 Chrome™ 34 4 Connections 11 10.5 App Lock 34 4.1 Tips on Connections 11 10.6 Widgets 35 4.2 EasyLink HDMI CEC 12 10.7 Remove Apps and Widgets 35 4.3 CI+ CAM with Smart Card 13 10.8 Clear Internet Memory 35 4.4 Set-Top Box - STB 14 10.9 Android Settings 35 4.5 Satellite Receiver 14 10.10 Terms of Use - Apps 36 4.6 Home Theatre System - HTS 15 4.7 Blu-ray Disc Player 16 11 Video on Demand 37 4.8 DVD Player 16 11.1 About Video on Demand 37 4.9 Game Console 17 11.2 Rent a Movie 37 4.10 Gamepad 17 11.3 Streaming 37 4.11 USB Hard Drive 18 12 TV on Demand 38 4.12 USB Keyboard or Mouse -

Overview of the MPEG 4 Standard

).4%2.!4)/.!,/2'!.)3!4)/.&/234!.$!2$)3!4)/. /2'!.)3!4)/.).4%2.!4)/.!,%$%./2-!,)3!4)/. )3/)%#*4#3#7' #/$).'/&-/6).'0)#452%3!.$!5$)/ )3/)%#*4#3#7'. $ECEMBER-AUI 3OURCE 7'-0%' 3TATUS &INAL 4ITLE -0%' /VERVIEW -AUI6ERSION %DITOR 2OB+OENEN /VERVIEWOFTHE-0%' 3TANDARD %XECUTIVE/VERVIEW MPEG-4 is an ISO/IEC standard developed by MPEG (Moving Picture Experts Group), the committee that also developed the Emmy Award winning standards known as MPEG-1 and MPEG-2. These standards made interactive video on CD-ROM and Digital Television possible. MPEG-4 is the result of another international effort involving hundreds of researchers and engineers from all over the world. MPEG-4, whose formal ISO/IEC designation is ISO/IEC 14496, was finalized in October 1998 and became an International Standard in the first months of 1999. The fully backward compatible extensions under the title of MPEG-4 Version 2 were frozen at the end of 1999, to acquire the formal International Standard Status early 2000. Some work, on extensions in specific domains, is still in progress. MPEG-4 builds on the proven success of three fields: • Digital television; • Interactive graphics applications (synthetic content) ; • Interactive multimedia (World Wide Web, distribution of and access to content) MPEG-4 provides the standardized technological elements enabling the integration of the production, distribution and content access paradigms of the three fields. More information about MPEG-4 can be found at MPEG’s home page (case sensitive): http://www.cselt.it/mpeg . This web page contains links to a wealth of information about MPEG, including much about MPEG-4, many publicly available documents, several lists of ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ and links to other MPEG-4 web pages. -

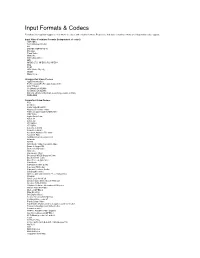

Input Formats & Codecs

Input Formats & Codecs Pivotshare offers upload support to over 99.9% of codecs and container formats. Please note that video container formats are independent codec support. Input Video Container Formats (Independent of codec) 3GP/3GP2 ASF (Windows Media) AVI DNxHD (SMPTE VC-3) DV video Flash Video Matroska MOV (Quicktime) MP4 MPEG-2 TS, MPEG-2 PS, MPEG-1 Ogg PCM VOB (Video Object) WebM Many more... Unsupported Video Codecs Apple Intermediate ProRes 4444 (ProRes 422 Supported) HDV 720p60 Go2Meeting3 (G2M3) Go2Meeting4 (G2M4) ER AAC LD (Error Resiliant, Low-Delay variant of AAC) REDCODE Supported Video Codecs 3ivx 4X Movie Alaris VideoGramPiX Alparysoft lossless codec American Laser Games MM Video AMV Video Apple QuickDraw ASUS V1 ASUS V2 ATI VCR-2 ATI VCR1 Auravision AURA Auravision Aura 2 Autodesk Animator Flic video Autodesk RLE Avid Meridien Uncompressed AVImszh AVIzlib AVS (Audio Video Standard) video Beam Software VB Bethesda VID video Bink video Blackmagic 10-bit Broadway MPEG Capture Codec Brooktree 411 codec Brute Force & Ignorance CamStudio Camtasia Screen Codec Canopus HQ Codec Canopus Lossless Codec CD Graphics video Chinese AVS video (AVS1-P2, JiZhun profile) Cinepak Cirrus Logic AccuPak Creative Labs Video Blaster Webcam Creative YUV (CYUV) Delphine Software International CIN video Deluxe Paint Animation DivX ;-) (MPEG-4) DNxHD (VC3) DV (Digital Video) Feeble Files/ScummVM DXA FFmpeg video codec #1 Flash Screen Video Flash Video (FLV) / Sorenson Spark / Sorenson H.263 Forward Uncompressed Video Codec fox motion video FRAPS: -

Petter Sandvik Formal Modelling for Digital Media Distribution

Petter Sandvik Formal Modelling for Digital Media Distribution Turku Centre for Computer Science TUCS Dissertations No 206, November 2015 Formal Modelling for Digital Media Distribution Petter Sandvik To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Science and Engineering at Åbo Akademi University, for public criticism in Auditorium Gamma on November 13, 2015, at 12 noon. Åbo Akademi University Faculty of Science and Engineering Joukahainengatan 3-5 A, 20520 Åbo, Finland 2015 Supervisors Associate Professor Luigia Petre Faculty of Science and Engineering Åbo Akademi University Joukahainengatan 3-5 A, 20520 Åbo Finland Professor Kaisa Sere Faculty of Science and Engineering Åbo Akademi University Joukahainengatan 3-5 A, 20520 Åbo Finland Reviewers Professor Michael Butler Electronics and Computer Science Faculty of Physical Sciences and Engineering University of Southampton Highfield, Southampton SO17 1BJ United Kingdom Professor Gheorghe S, tefănescu Computer Science Department University of Bucharest 14 Academiei Str., Bucharest, RO-010014 Romania Opponent Professor Michael Butler Electronics and Computer Science Faculty of Physical Sciences and Engineering University of Southampton Highfield, Southampton SO17 1BJ United Kingdom ISBN 978-952-12-3294-7 ISSN 1239-1883 To tose who are no longr wit us, and to tose who wil be here afer we are gone i ii Abstract Human beings have always strived to preserve their memories and spread their ideas. In the beginning this was always done through human interpretations, such as telling stories and creating sculptures. Later, technological progress made it possible to create a recording of a phenomenon; first as an analogue recording onto a physical object, and later digitally, as a sequence of bits to be interpreted by a computer. -

The Definitive Guide

Mastering the MP3 Audio Experience The Definitive Guide ~~/ REILLY® Scot Hacker Facebook's Exhibit No. 1062 Page 1 MP3 The Definitive Guide Facebook's Exhibit No. 1062 Page 2 MP3 The Definitive Guide Scot Hacker O'REILLY® Beijing · Cambridge · Farnham · KO!n · Paris · Sebastopol · Taipei · Tokyo Facebook's Exhibit No. 1062 Page 3 MP3: The Definitive Guide by Scot Hacker Copyright © 2000 O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published by O'Reilly & Associates, Inc., 101 Morris Street, Sebastopol, CA 95472. Editor: Simon Hayes Production Editor: Maureen Dempsey Cover Designer: Hanna Dyer Printing History: March 2000: First Edition. Nutshell Handbook, the Nutshell Handbook logo, and the O'Reilly logo are registered trademarks. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in caps or initial caps. The association between the image of a hermit crab and MP3 is a trademark of O'Reilly & Associates, Inc. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hacker, Scot MP3: the definitive guide/Scot Hacker.-1st ed. p. em. ISBN 1-56592-661-7 (alk. paper) 1. MP3. 2.MP3 players. 3. Music-Computer programs. 4. Internet (Computer network) Computer programs. I. Title. ML74.4.M6 H33 2000 780' .285'65-dc21 00-025403 ISBN: 1-56592-661-7 [4/00] [M] Facebook's Exhibit No. -

Video Compression: MPEG-4 and Beyond Video Compression: MPEG-4 and Beyond

Video Compression: MPEG-4 and Beyond Video Compression: MPEG-4 and Beyond Ali Saman Tosun, [email protected] Abstract Technological developments in the networking technology and the computers make use of video possible. Storing and transmitting uncompressed raw video is not a good idea, it requires large storage space and bandwidth. Special algorithms which take the characteristics of the video into account can compress the video with high compression ratio. In this paper I will give a overview of the standardization efforts on video compression: MPEG-1, MPEG-2, MPEG-4, MPEG-7, and I will explain the current video compression trends briefly. See also: Multimedia Networking Products | Multimedia Over IP: RSVP, RTP, RTCP, RTSP | Multimedia Networking References | Books on Multimedia | Protocols for Multimedia on the Internet (Class Lecture) | Video over ATM networks | Multimedia networks: An introduction (Talk by Prof. Jain) | Other Reports on Recent Advances in Networking Back to Raj Jain's Home Page Table of Contents: ● 1. Introduction ● 2. H.261 ● 3. H.263 ● 4. H.263+ ● 5. MPEG ❍ 5.1 MPEG-1 ❍ 5.2 MPEG-2 ❍ 5.3 MPEG-3 ❍ 5.4 MPEG-4 ❍ 5.5 MPEG-7 ● 6. J.81 ● 7. Fractal-Based Coding ● 8. Model-based Video Coding http://www.cis.ohio-state.edu/~jain/cis788-99/compression/index.html (1 of 13) [2/7/2000 10:39:09 AM] Video Compression: MPEG-4 and Beyond ● 9. Scalable Video Coding ● 10 . Wavelet-based Coding ● Summary ● References ● List of Acronyms 1. Introduction Over the last couple of years there has been a great increase in the use of video in digital form due to the popularity of the Internet. -

Stephanie Preißner, Christina Raasch, and Tim Schweisfurth

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Preißner, Stephanie; Raasch, Christina; Schweisfurth, Tim Working Paper Is necessity the mother of disruption? Kiel Working Paper, No. 2097 Provided in Cooperation with: Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW) Suggested Citation: Preißner, Stephanie; Raasch, Christina; Schweisfurth, Tim (2017) : Is necessity the mother of disruption?, Kiel Working Paper, No. 2097, Kiel Institute for the World Economy (IfW), Kiel This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/172535 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu KIEL WORKING PAPER Is Necessity the Mother of Disruption? No. 2097 December 2017 Stephanie Preißner, Christina Raasch, and Tim Schweisfurth Kiel Institute for the World Economy ISSN 2195–7525 KIEL WORKING PAPER NO.