A Survey of Indian Assimilation in Eastern Sonora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lunes 12 De Julio De 2021. CCVIII Número 4 Secc. I

• • • • • • DESARROLLO TERRITORIAL SliC~ETARÍA OE Oi:.SAJU tCLLO ~ C fl:A.fUO, TE~ JU TOQfA L V \IRB,A_NO AVISO DE DESLINDE SECRETARÍA DE DESARROLLO AGRARIO, TERRITORIAL Y URBANO Aviso de medición y deslinde del predio de presunta propiedad nacional denominado "LAS UVALAMAS" con una superficie aproximada de 83-27-38.940 hectáreas, ubicado en el Municipio de SUAQUI GRANDE, SONORA. La Dirección General de la Propiedad Rural, de la Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano, mediante Oficio núm. ll-210-DGPR-14607, de fecha 16 de diciembre de 2020, autorizó el deslinde y medición del predio presuntamente propiedad de la nación, arriba mencionado. Mediante el mismo oficio, se autorizó al suscrito lng. Mario Toledo Padilla, a llevar a cabo la medición y deslinde del citado predio, por lo que, en cumplimiento de los artículos 14 Constitucional, 3 de la Ley Federal de Procedimiento Administrativo, 160 de la Ley Agraria; 101, 104 y 105 Fracción I del Reglamento de la Ley Agraria en Materia de Ordenamiento de la Propiedad Rural, se publica, por una sola vez, en el Diario Oficial de la Federación, en el Periódico Oficial del Gobierno del Estado de Sonora, y en el periódico de mayor circulación de la entidad federativa de que se trate con efectos de notificación a los propietarios, poseedores, colindantes y todo aquel que considere que los trabajos de deslinde lo pudiesen afectar, a efecto de que dentro del plazo de 30 días hábiles contados a partir de la publicación del presente Aviso en el Diario Oficial de la Federación, comparezcan ante el suscrito para exponer lo que a su derecho convenga, así como para presentar la documentación que fundamente su dicho en copia certificada o en copia simple, acompañada del documento original para su cotejo, en términos de la fracción 11 del artículo 15-A de la Ley Federal de Procedimiento Administrativo. -

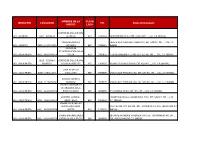

MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD NOMBRE DE LA UNIDAD CLAVE LADA TEL Domiciliocompleto

NOMBRE DE LA CLAVE MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD TEL DomicilioCompleto UNIDAD LADA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 001 - ACONCHI 0001 - ACONCHI ACONCHI 623 2330060 INDEPENDENCIA NO. EXT. 20 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84920) CASA DE SALUD LA FRENTE A LA PLAZA DEL PUEBLO NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. 001 - ACONCHI 0003 - LA ESTANCIA ESTANCIA 623 2330401 (84929) UNIDAD DE DESINTOXICACION AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 3382875 7 ENTRE AVENIDA 4 Y 5 NO. EXT. 452 NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) 0013 - COLONIA CENTRO DE SALUD RURAL 002 - AGUA PRIETA MORELOS COLONIA MORELOS 633 3369056 DOMICILIO CONOCIDO NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) CASA DE SALUD 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0009 - CABULLONA CABULLONA 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84305) CASA DE SALUD EL 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0046 - EL RUSBAYO RUSBAYO 999 9999999 UNICA CALLE PRINCIPAL NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84306) CENTRO ANTIRRÁBICO VETERINARIO AGUA 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA SONORA 999 9999999 5 Y AVENIDA 17 NO. EXT. NO. INT. , , COL. C.P. (84200) HOSPITAL GENERAL, CARRETERA VIEJA A CANANEA KM. 7 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , , COL. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA AGUA PRIETA 633 1222152 C.P. (84250) UNEME CAPA CENTRO NUEVA VIDA AGUA CALLE 42 NO. EXT. S/N NO. INT. , AVENIDA 8 Y 9, COL. LOS OLIVOS C.P. 002 - AGUA PRIETA 0001 - AGUA PRIETA PRIETA 633 1216265 (84200) UNEME-ENFERMEDADES 38 ENTRE AVENIDA 8 Y AVENIDA 9 NO. EXT. SIN NÚMERO NO. -

Ayuntamiento De Hermosillo - Cities 2019

Ayuntamiento de Hermosillo - Cities 2019 Introduction (0.1) Please give a general description and introduction to your city including your city’s reporting boundary in the table below. Administrative Description of city boundary City Metropolitan Hermosillo is the capital of the Sonora State in Mexico, and a regional example in the development of farming, animal husbandry and boundary area manufacturing industries. Hermosillo is advantaged with extraordinarily extensive municipal boundaries; its metropolitan area has an extension of 1,273 km² and 727,267 inhabitants (INEGI, 2010). Located on coordinates 29°05’56”N 110°57’15”W, Hermosillo’s climate is desert-arid (Köppen-Geiger classification). It has an average rainfall of 328 mm per year and an average annual maximum temperature of 34.0 degrees Celsius. Mexico’s National Atlas of Zones with High Clean Energy Potential, distinguishes Hermosillo as place of high solar energy yield, with a potential of 6,000-6,249 Wh/m²/day. Hermosillo is a strategic place in Mexico’s business network. Situated about 280 kilometers from the United States border (south of Arizona), Hermosillo is a key member of the Arizona-Sonora mega region and a link of the CANAMEX corridor which connects Canada, Mexico and the United States. The city is among the “top 5 best cities to live in Mexico”, as declared by the Strategic Communication Office (IMCO, 2018). Hermosillo’s cultural heritage, cleanliness, low cost of living, recreational amenities and skilled workforce are core characteristics that make it a stunning place to live and work. In terms of governance, Hermosillo’s status as the capital of Sonora gives it a lot of institutional and political advantages, particularly in terms of access to investment programs and resources, as well as power structures that matter in urban decision-making. -

Wrote in Cucurpe, on 30Th April 1689, to His Aunt Francisca Adlmann in Škofja Loka, Slovenia

UDK 929 Kappus M. A. A LETTER OF MARCUS ANTONIUS KAPPUS TO EUSEBIUS FRANCISCUS KINO (SONORA IN1690) Tomaž Nabergoj INTRODUCTION The life and work of the Slovene Jesuit, Marcus Antonius Kappus (1657 -1717) who, three centuries ago, worked as a missionary in Sonora, north-west Mexico, has, in recent years, been the subject of several short studies in Slovenia. In this journal, Professor Janez Stanonik has, so far, published five letters which Kappus sent home to his relatives and friends, and one letter which he sent to hi s friend in Vienna, 1 as well as a study on the collection of poems (276 chronograms) in Latin, which Kappus published in Mexico City, in 1708, entitled IHS. Enthusiasmus sive solemnes !udi poe tici. 2 Prompted by the above publications, the author of this paper spent a month in Sonora while journeying in Mexico in 1991. In Archivo General de la Naci6n (the general Mexican archives) in Mexico City, he happened to find another letter written by Marcus Antonius Kappus. The letter comprises two A4 pages and is kept in Archivo Hist6rico de la Hacienda, legajo 279, expediente 19.3 This, hitherto unpublished document, was written by Kappus on 25th November 1690, in Cucurpe, and is addressed to Eusebius Franciscus Kino, his superior. Chronologically, it is one of his earliest preserved letters. Among those so far published, as far as we know, it is the only one preserved in original. At the same time this is Kappus' second earliest preserved letter written in Sonora. The first he wrote in Cucurpe, on 30th April 1689, to his aunt Francisca Adlmann in Škofja Loka, Slovenia. -

An Ethnographicsurvey

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 186 Anthropological Papers, No. 65 THE WARIHIO INDIANS OF SONORA-CHIHUAHUA: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC SURVEY By Howard Scott Gentry 61 623-738—63- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 65 Introduction 69 Informants and acknowledgments 69 Nominal note 71 Peoples of the Rio Mayo and Warihio distribution 73 Habitat 78 Arroyos 78 Canyon features 79 Hills 79 Cliffs 80 Sierra features - 80 Plants utilized 82 Cultivated plants 82 Wild plants 89 Root and herbage foods 89 Seed foods 92 Fruits 94 Construction and fuel 96 Medicinal and miscellaneous uses 99 Use of animals 105 Domestic animals 105 Wild animals and methods of capture 106 Division of labor 108 Shelter 109 Granaries 110 Storage caves 111 Elevated structures 112 Substructures 112 Furnishings and tools 112 Handiwork 113 Pottery 113 The oUa 114 The small bowl 115 Firing 115 Weaving 115 Woodwork 116 Rope work 117 Petroglyphs 117 Transportation 118 Dress and ornament 119 Games 120 Social institutions 120 Marriage 120 The selyeme 121 Birth 122 Warihio names 123 Burial 124 63 64 CONTENTS PAGE Ceremony 125 Tuwuri 128 Pascola 131 The concluding ceremony 132 Myths 133 Creation myth 133 Myth of San Jose 134 The cross myth 134 Tales of his fathers 135 Fighting days 135 History of Tu\\njri 135 Songs of Juan Campa 136 Song of Emiliano Bourbon 136 Metamorphosis in animals 136 The Carbunco 136 Story of Juan Antonio Chapapoa 136 Social customs, ceremonial groups, and extraneous influences 137 Summary and conclusions 141 References cited 143 ILLUSTEATIONS PLATES (All plates follow p. 144) 28. a, Juan Campa and Warihio boy. -

A Distributional Survey of the Birds of Sonora, Mexico

52 A. J. van Rossem Occ. Papers Order FALCONIFORMES Birds of PreY Family Cathartidae American Vultures Coragyps atratus (Bechstein) Black Vulture Vultur atratus Bechstein, in Latham, Allgem. Ueb., Vögel, 1, 1793, Anh., 655 (Florida). Coragyps atratus atratus van Rossem, 1931c, 242 (Guaymas; Saric; Pesqueira: Obregon; Tesia); 1934d, 428 (Oposura). — Bent, 1937, 43, in text (Guaymas: Tonichi). — Abbott, 1941, 417 (Guaymas). — Huey, 1942, 363 (boundary at Quito vaquita) . Cathartista atrata Belding, 1883, 344 (Guaymas). — Salvin and Godman, 1901. 133 (Guaymas). Common, locally abundant, resident of Lower Sonoran and Tropical zones almost throughout the State, except that there are no records as yet from the deserts west of longitude 113°, nor from any of the islands. Concentration is most likely to occur in the vicinity of towns and ranches. A rather rapid extension of range to the northward seems to have taken place within a relatively few years for the species was not noted by earlier observers anywhere north of the limits of the Tropical zone (Guaymas and Oposura). It is now common nearly everywhere, a few modern records being Nogales and Rancho La Arizona southward to Agiabampo, with distribution almost continuous and with numbers rapidly increasing southerly, May and June, 1937 (van Rossem notes); Pilares, in the north east, June 23, 1935 (Univ. Mich.); Altar, in the northwest, February 2, 1932 (Phillips notes); Magdalena, May, 1925 (Dawson notes; [not noted in that locality by Evermann and Jenkins in July, 1887]). The highest altitudes where observed to date are Rancho La Arizona, 3200 feet; Nogales, 3850 feet; Rancho Santa Bárbara, 5000 feet, the last at the lower fringe of the Transition zone. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I Sonora, Mexico Municipal Development Project

I fJl-~-5r3 I 5 5 I 9 7 7 I SONORA, MEXICO I MUNICIPAL DEVELOPMENT PROJECT: DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT OF I THE CITY OF AGUA PRIETA I September 1996 I I Prepared for I U.S. Agency for International Development I By Frank B. Ohnesorgen I Ramon R. Osuna I Julio Zapata I I INTERNATIONAL CITY/COUNTY MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATION Municipal Development and Management USAID Contract No. PCE-I008-Q-00-5002-00 -I USAID Project No. 940-1008 Delivery Order No.5 I I I I I TABLE OF CONTENTS I 1 INTRODUCTION 1 I 2 METHODOLOGY 2 I 3 GENERAL MUNICIPAL CHARACTERISTICS 2 4 DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT AND OBSERVATIONS 2 I 4.1 Office ofthe Mayor (Presidente Municipal) and Councilmembers (Regidores) 2 4.2 The Office ofthe Municipal Secretary (Secretario Municipal) 3 4.3 The Office ofSolidarity Programs (Director de Programas de Solideridad) 4 I 4.4 The Office ofHuman Resources (Personnel) (Director de Recursos Humanos) 4 4.5 The Office ofMunicipal Controller (Contraloria Municipal) 5 4.6 The Office ofPublic Works (Directora de Obras Pilblicas) 6 I 4.7 The Office ofIntegral Family Development (Desarrollo Integral de Familias) 6 4.8 The Office ofPublic Services (Director de Servicios Pilblicos) 7 4.9 The Office ofMunicipal Treasurer (Tesorero Municipal) 7 I 4.10 The Office ofProcurator (Sindico Procurador) 8 I 5 GENERAL DIAGNOSTIC OBSERVATIONS 9 6 RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE MAYOR AND COUNCIL 10 I I I I I I I I I I I -111- ABSTRACT I The Sonora, Mexico Municipal Development Project (SMMD) was initiated in response to the local government demand for autonomy in Mexico. -

Project Proposal

Board Document BD 2007-XX August 29, 2007 Border Environment Cooperation Commission Wastewater Collection Project in Agua Prieta, Sonora. 1. General Criteria 1.a Project Type The project consists of improving and expanding the wastewater collection system for the community of Agua Prieta, in the municipality of Agua Prieta, Sonora. This project belongs to BECC's Wastewater Treatment and Domestic Water and Wastewater Hookups Sectors. 1.b Project Categories The project belongs to the category of Community Environmental Infrastructure Projects – Community-wide Impact. The project will improve wastewater collection quality service in the community of Agua Prieta resulting in a positive impact to this community. 1.c Project Location and Community Profile The State of Sonora is located in the northeastern part of the Republic of Mexico, adjacent to the United States of America. Agua Prieta, Sonora is located in the northeastern part of the State of Sonora and neighbors the City of Douglas, Arizona, USA. About 47% of the population in Agua Prieta is employed in maquilas, commerce or by rendering services. The rest of the population is employed in agricultural related activities. The following figure shows the geographic location of Agua Prieta. 1 Board Document BD 2007-XX BECC Certification Document Agua Prieta, Sonora Demographics Population projections prepared during the development of the Final Design of the Wastewater Collection System1 for Agua Prieta, Sonora were based on census data obtained by the National Institute for Statistics, Geography, and Information (INEGI 2000 for its initial in Spanish) and the National Population Council (CONAPO for its initial in Spanish). The current population (2007) has been estimated to be 70,523 inhabitants and estimations for the year 2027 forecast were 79,143 inhabitants. -

Health Consultation Trans-Border Exposure to Smoke from Refuse

Health Consultation Trans-border Exposure to Smoke From a Refuse Fire in Naco, Sonora, Mexico December 1 to December 5, 2001 Naco, Arizona, USA, and Naco, Sonora, Mexico Prepared by Arizona Department of Health Services Office of Environmental Health Environmental Health Consultation Services under cooperative agreement with the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry March 2002 Introduction A refuse dump near Naco, Sonora, Mexico, caught fire and burned from December 1 to December 5, 2001. The fire, which consumed large quantities of household refuse, also generated a large quantity of smoke. During this period, considerable smoke was intermittently present in Naco, Arizona. Persons up to 17 miles away from the fire reported smelling the smoke. At night in the Naco area, smoke concentrations were generally higher when weather conditions caused smoke to settle in residential neighborhoods on both sides of the border. The Arizona Department of Health Services and the Cochise County Health Department issued public health advisories for the evenings of December 1 and 2, 2001. The Naco, Arizona, Port of Entry closed during periods of heavy smoke to protect the health and safety of employees and travelers. The Cochise County Board of Supervisors declared a state of emergency to gain access to state and federal resources. This report summarizes the events that occurred during the fire and analyzes the data collected by the Arizona Department of Health Services and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality to determine the extent of the public health threat from the fire. Background Saturday, December 1, 2001 The Cochise County Health Department received calls from citizens complaining about the smoke. -

Spain's Arizona Patriots in Its 1779-1783 War

W SPAINS A RIZ ONA PA TRIOTS J • in its 1779-1783 WARwith ENGLAND During the AMERICAN Revolutuion ThirdStudy of t he SPANISH B ORDERLA NDS 6y Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough ~~~i~!~~¸~i ~i~,~'~,~'~~'~-~,:~- ~.'~, ~ ~~.i~ !~ :,~.x~: ~S..~I~. :~ ~-~;'~,-~. ~,,~ ~!.~,~~~-~'~'~ ~'~: . Illl ........ " ..... !'~ ~,~'] ." ' . ,~i' v- ,.:~, : ,r~,~ !,1.. i ~1' • ." ~' ' i;? ~ .~;",:I ..... :"" ii; '~.~;.',',~" ,.', i': • V,' ~ .',(;.,,,I ! © Copyright 1999 ,,'~ ;~: ~.~:! [t~::"~ "~, I i by i~',~"::,~I~,!t'.':'~t Granville W. and N.C. Hough 3438 Bahia blanca West, Aprt B Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 k ,/ Published by: SHHAR PRESS Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 http://mcmbers.aol.com/shhar SHHARPres~aol.com (714) $94-8161 ~I,'.~: Online newsletter: http://www.somosprimos.com ~" I -'[!, ::' I ~ """ ~';I,I~Y, .4 ~ "~, . "~ ! ;..~. '~/,,~e~:.~.=~ ........ =,, ;,~ ~c,z;YA':~-~A:~.-"':-'~'.-~,,-~ -~- ...... .:~ .:-,. ~. ,. .... ~ .................. PREFACE In 1996, the authors became aware that neither the NSDAR (National Society for the Daughters of the American Revolution) nor the NSSAR (National Society for the Sons of the American Revolution) would accept descendants of Spanish citizens of California who had donated funds to defray expenses ,-4 the 1779-1783 war with England. As the patriots being turned down as suitable ancestors were also soldiers,the obvious question became: "Why base your membership application on a money contribution when the ancestor soldier had put his life at stake?" This led to a study of how the Spanish Army and Navy had worked during the war to defeat the English and thereby support the fledgling English colonies in their War for Independence. After a year of study, the results were presented to the NSSAR; and that organization in March, 1998, began accepting descendants of Spanish soldiers who had served in California. -

Sonora, Mexico

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development SONORA, MEXICO, Sonora is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico and has made great strides in Sonora, building its human capital and skills. How can Sonora turn the potential of its universities and technological institutions into an active asset for economic and Mexico social development? How can it improve the equity, quality and relevance of education at all levels? Jaana Puukka, Susan Christopherson, This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional Patrick Dubarle, Jocelyne Gacel-Ávila, reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series Vera Pavlakovich-Kochi of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. Sonora, Mexico CONTENTS Chapter 1. Human capital development, labour market and skills Chapter 2. Research, development and innovation Chapter 3. Social, cultural and environmental development Chapter 4. Globalisation and internationalisation Chapter 5. Capacity building for regional development ISBN 978- 92-64-19333-8 89 2013 01 1E1 Higher Education in Regional and City Development: Sonora, Mexico 2013 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. -

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT of the INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PRELIMINARY DEPOSIT-TYPE MAP of NORTHWESTERN MEXICO by Kenneth R

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PRELIMINARY DEPOSIT-TYPE MAP OF NORTHWESTERN MEXICO By Kenneth R. Leonard U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 89-158 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Any use of trade, product, firm, or industry names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Menlo Park, CA 1989 Table of Contents Page Introduction..................................................................................................... i Explanation of Data Fields.......................................................................... i-vi Table 1 Size Categories for Deposits....................................................................... vii References.................................................................................................... viii-xx Site Descriptions........................................................................................... 1-330 Appendix I List of Deposits Sorted by Deposit Type.............................................. A-1 to A-22 Appendix n Site Name Index...................................................................................... B-1 to B-10 Plate 1 Distribution of Mineral Deposits in Northwestern Mexico Insets: Figure 1. Los Gavilanes Tungsten District Figure 2. El Antimonio District Figure 3. Magdalena District Figure 4. Cananea District Preliminary Deposit-Type Map of