7 *'!G 2 7 2010 Billy Ray Irick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And the a GATHERING of GUNS—TV WESTERN REUNION

Special And the Memorial Tribute to MONTE HALE with guest Mrs. Foy (Sharon) Willing. A GATHERING OF GUNS—TV WESTERN REUNION June 4-6, '09, at Whispering Woods Hotel and Conference Center, Olive Branch, Mississippi (just a quick 20 minutes south of Memphis, Tennessee. Shuttle service from airport available. ) Robert Fuller Will Hutchins James Drury Ty Hardin Denny Miller Peter Brown “Bronco” “Laramie” “Sugarfoot” “The Virginian” “Wagon Train” “Lawman” “Wagon Train” WC Columnist for 15 years WC Columnist “Laredo” Jan Merlin Johnny Washbrook Anne Helm Henry Darrow Donald May Don Collier “Rough Riders” “My Friend Flicka” Our Leading “High Chaparral” “Colt .45” “The Outlaws” “High Chaparral” Lady Also Jeff Connors, Chuck Connors’ son, will attend with his father’s “Rifleman” rifle. Special Events include: %%% Three viewing rooms showing over 79 hours of western TV shows %%% $100 Prize TV Western Trivia Contest open to everyone. %%% Two live radio show recreations featuring attending stars %%% Daily celebrity panel discussions including special phone hookups with Kelo (“26 Men”) Henderson, Clint (“Cheyenne”) Walker, Jimmy (“Annie Oakley”) Hawkins, stuntlady Jeannie Epper, Linda Cristal (“High Chaparral”), Robert Horton (“Wagon Train”). %%% Memorabilia Auction %%% Dealer’s Room with all stars signing photos %%% One Festival rate covers all: $20 per day per person. $25 a couple. $60 all three days per person. $75 couple. Les Gilliam Entertainment by Additional: Saturday Night Banquet/Awards Presentation/Entertainment: $40 per person. The Oklahoma %%% Continuing updated information at <www.westernclippings.com> and Balladeer <www.memphisfilmfestival.com> %%% Whispering Woods hotel reservations: (662) 895-2941. Festival Room Rate is $89. Ray Nielsen Boyd Magers WESTERN CLIPPINGS MEMPHIS FILM FESTIVAL OR 1312 Stagecoach Rd SE PO Box 87, Conway, AR 72033 Albuquerque, NM 87123 (501) 499-0444 email: [email protected] (505) 292-0049 email:[email protected] . -

BCE- Carpetted with the Fallen Blossoms

sy rlii to health minister .John Reynolds, MLA for West Vancouver-Howe Sound has been appointed parliamentary secretary to Stephen Rogers, Minister of Health. Premier Bennett made the appointment on Monday, Feb. 24. Previously Reynolds was parliamentary secretary to Grace McCarthy. , Pavilion Complex at Expo 86 features a 300 square professionals will compete in a daily loggers' sports metre floating stage (right) where more abann 30 show. MRS. WOBNIE McCARTWBI Sales Representative Trustee concerned BUS: 892-5924 VANC. DIRECT: 689-581E REALTY RES: 898-5941 PAGER: 8926901 no. 621 Diamond Head -Mountain Retreat $25,000 about proposed Large Lot -Highlands $15,000 Large Heme -Estates $72,900 Oldar H6m43 with chum -Dentville $62,900 new program 2 Town houses -VuI ley cl iffe $49,900 School trustee Ardis- addit ional information and She also expressed her Lawrence told the school answers questions. Many concern that 'it would be . Excelht Rancher &ackendale $57,900 board meeting last Wedne- schools use segregated cla- taught to mixed groups. Unique Home -Highlands $87,988 sday she was concerned sses and in most schools "Some of the information is Dream Home -Highlands SI64,OOQ about a proposed new pro- preliminary meetings are necessary," she said, "but it Beautiful Split Level -Highlands ' gram which Mike Edwards, held with parents to discuss should not be given in '$84,900 principal of Signal Hill El- the project. depth." . Cute Starter Home - Brackendale , $61,980 ementary School, had asked The request sparked some Lawrence said she believed 3Bedroom, 3 Both Condo -Brackendale $47,900 to be introduced to the lively discussion at the mee- that young people should get Sprawling Rancher -Brackendale Grade 5, 6 and 7 students. -

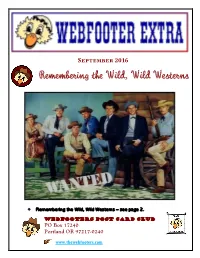

The Webfooter

September 2016 Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns – see page 2. Webfooters Post Card Club PO Box 17240 Portland OR 97217-0240 www.thewebfooters.com Remembering the Wild, Wild Westerns Before Batman, before Star Trek and space travel to the moon, Westerns ruled prime time television. Warner Brothers stable of Western stars included (l to r) Will Hutchins – Sugarfoot, Peter Brown – Deputy Johnny McKay in Lawman, Jack Kelly – Bart Maverick, Ty Hardin – Bronco, James Garner – Bret Maverick, Wade Preston – Colt .45, and John Russell – Marshal Dan Troupe in Lawman, circa 1958. Westerns became popular in the early years of television, in the era before television signals were broadcast in color. During the years from 1959 to 1961, thirty-two different Westerns aired in prime time. The television stars that we saw every night were larger than life. In addition to the many western movie stars, many of our heroes and role models were the western television actors like John Russell and Peter Brown of Lawman, Clint Walker on Cheyenne, James Garner on Maverick, James Drury as the Virginian, Chuck Connors as the Rifleman and Steve McQueen of Wanted: Dead or Alive, and the list goes on. Western movies that became popular in the 1940s recalled life in the West in the latter half of the 19th century. They added generous doses of humor and musical fun. As western dramas on radio and television developed, some of them incorporated a combination of cowboy and hillbilly shtick in many western movies and later in TV shows like Gunsmoke. -

Bridgewater, but No Had Been Hoping for a Daughter Coastal Evacuation Was Ordered

MANCHESTER Condo garbage video list here Miami, Lions vie could be costly short but cheap for national title ... page 3 , ... page 11 ... page 14 anrlirBtrr Mrralft Manchester — A City ol Village Charm Friday, Jan. 2,1987 30 Cents ‘Vicious’ storm baby J -If'-.; of new year hits Northeast; came early Bv George Loyifg A coast in danger Herald Reporter Beverly Carvalho of Glastonbury said she had not expected to be a By Peter Brown sive," with flooding and beach mother until Saturday. That was The Associated Press erosion posing "serious threats to when doctors told her she would both life and property.” give birth to her first child. Authorities urged evacuations Today’s high tide — at 12:24 p.m. Nobody told her daughter, along Maine and New Hampshire’s — was expected to be 2-3 feet above however. N seacoast today as a fierce winter normal because of a rare alignment Danielle Telzina Carvalho be storm, coupled with high tides of the sun, moon and Earth. It has came the first baby bom in 1987 at caused by a rare astronomical occurred only three times since Manchester Memorial Hospital, alignment, swept up the East Coast 1912, the weather service said. the hospital announced today. into New England after causing six Sustained winds of more than 40 Danielle, weighing 6 pounds and 6 deaths and millions of dollars in mph were recorded at Isle of Shoals ounces, with blond hair and meas this morning, said John Gifford of property damage. uring 19 inches .was bom to Beverly the New Hampshire’s state Civil "Anyone living or working along and Daniel Carvalho at 5:48 a.m. -

TV Theme Songs

1 TV Themes Table of Contents Page 3 Cheers Lawman - 38 4 Bonanza Wyatt Earp - 39 5 Happy Days Bob Hope - 4 6 Hawaii 5-O Jack Benny - 43 6 Daniel Boone 77 Sunset Strip - 44 7 Addams Family Hitchcock - 46 8 “A” Team Kotter - 48 9 Popeye You Bet Your Life - 50 11 Dick Van Dyke Star Trek - 52 11 Mary Tyler Moore Godfrey - 54 13 Gomer Pyle Casper - 55 13 Andy Griffith Odd Couple - 56 14 Gilligan’s Island Green Acres - 57 15 Davey Crockett 16 Flipper Real McCoys - 59 16 Cheyenne Beverly Hill Billies - 60 17 The Rebel Hogan's Heroes - 61 17 Mash Love Boat - 62 19 All in the Family Mission Impossible - 63 20 Mike Hammer McDonalds - 65 21 Peter Gunn Oscar Myers - 65 22 Maverick Band Aids - 65 23 Lawman Budweiser - 66 24 Wyatt Earp 24 Bob Hope 26 Jack Benny 27 77 Sunset Strip 27 Alfred Hitchcock 28 Welcome Back Kotter 28 You Bet Your Life (Groucho Marx) 29 Star Trek 31 Arthur Godfrey 31 Casper the Friendly Ghost 32 Odd Couple 32 Green Acres 33 The Real McCoys 34 Beverly Hillbillies 35 Hogan’s Heroes 35 Love Boat 36 Mission Impossible 37 Mr. Ed 37 Dream Alone with Me (Perry Como) 2 2 Cheers - 1982-1993 – Music by Gary Portnoy & Judy Hart Angelo This popular theme song was written by Gary Portnoy and Judy Hart Angelo when both were at crossroads in their respective careers. Judy was having dinner and seated next to a Broadway producer who was looking for someone to compose the score for his new musical. -

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Bob

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collections Bob Burke Autographs of Western Stars Collection Autographed Images and Ephemera Box 1 Folder: 1. Roy Acuff Black-and-white photograph of singer Roy Acuff with his separate autograph. 2. Claude Akins Signed black-and-white photograph of actor Claude Akins. 3. Alabama Signed color photograph of musical group Alabama. 4. Gary Allan Signed color photograph of musician Gary Allan. 5. Rex Allen Signed black-and-white photograph of singer, actor, and songwriter Rex Allen. 6. June Allyson Signed black-and-white photograph of actor June Allyson. 7. Michael Ansara Black-and-white photograph of actor Michael Ansara, matted with his autograph. 8. Apple Dumpling Gang Black-and-white signed photograph of Tim Conway, Don Knotts, and Harry Morgan in The Apple Dumpling Gang, 1975. 9. James Arness Black-and-white signed photograph of actor James Arness. 10. Eddy Arnold Signed black-and-white photograph of singer Eddy Arnold. 11. Gene Autry Movie Mirror, Vol. 17, No. 5, October 1940. Cover signed by Gene Autry. Includes an article on the Autry movie Carolina Moon. 12. Lauren Bacall Black-and-white signed photograph of Lauren Bacall from Bright Leaf, 1950. 13. Ken Berry Black-and-white photograph of actor Ken Berry, matted with his autograph. 14. Clint Black Signed black-and-white photograph of singer Clint Black. 15. Amanda Blake Signed black-and-white photograph of actor Amanda Blake. 16. Claire Bloom Black-and-white promotional photograph for A Doll’s House, 1973. Signed by Claire Bloom. 17. Ann Blyth Signed black-and-white photograph of actor and singer Ann Blyth. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

Ottawa to ~Eal with Broadcast Report 1 Non-Theatrica~ Indu~Try Looks OTTAWA - the Caplan- the Report Through the Various Communications and Culture

c I N E M A G • , R A D E NEW 5 • I Ottawa to ~eal with broadcast report 1 Non-theatrica~ indu~try looks OTTAWA - The Caplan- the report through the various Communications and Culture. to Ottawa for financial help Sauvageau report on broad- stages of examination. She has The members of this com casting has set off a flurry of ac- promised a n~w broadcasting mittee for the current par OTTAWA - Situation desper The interests of Canadian tivity within the department of act as a result of the study by liamentary session were ate repofts a federal govern non-theatrical producers and Communications as bureau- the end of the Conservative named Oct. 15 and DOC insid ment task force commissioned distributors should be the sub> crats weigh the implications of term of office. ers expect Jim Edwards (PC in May 1986 to study the non ject of stronger federal the political decisions which A thorough and exhaustive MP Edmonton South) to be theatrical film and video indus copyright legislation and a must be made; it will soon re- study of·the state of broadcast- elected president. During the try. joint federaUprovincial train ceive close scrutiny by the ing in Canada, the repo'rt has 1985 session, he served as the The 38-page report entitled ing program should be estab Commons. meet with general approval parliamentary secretary to the The Other Film Industry, re lished to help improve the use The Report of the Task within the industry, indicating minister of Communications. leased Oct. 6, recommends a of audiovisual materials in edu- Force on Broadcasting Policy - that the high expectations Edwards age 50 has spent $15 million per year support cation. -

Public Meeting Of

Public Meeting of THE NEW JERSEY LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS “Recreational Marijuana Hearings; second of three” LOCATION: Mount Teman A.M.E. Church DATE: March 27, 2018 160 Madison Avenue 10:00 a.m. Elizabeth, New Jersey MEMBERS OF CAUCUS PRESENT: Senator Ronald L. Rice, Chair Assemblywoman Shavonda E. Sumter, 2nd Vice Chair Assemblyman Jamel C. Holley Assemblywoman Mila M. Jasey ALSO PRESENT: Senator Joseph Cryan District 20 Senator Nicholas P. Scutari District 22 Assemblywoman Annette Quijano District 20 Patricia Perkins-Auguste Councilwoman-at-Large City of Elizabeth Hearing Recorded and Transcribed by The Office of Legislative Services, Public Information Office, Hearing Unit, State House Annex, PO 068, Trenton, New Jersey TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Reverend Timothy Levi Adkins-Jones Senior Pastor Bethany Baptist Church 2 Reverend Dr. Charles F. Boyer Pastor Bethel A.M.E. Church, Woodbury 3 Kevin A. Sabet, Ph.D. President and Chief Executive Officer Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM), and Director Drug Policy Institute University of Florida 13 Morgan Thompson Director Academic and Recovery Support Services Prevention Links, and The Raymond J. Lesniak Experience Strength and Hope Recovery High School 20 Mike Smeraglia Private Citizen 23 Corinne LaMarca Gasper Private Citizen 27 Luke D. Niforatos Chief of Staff and Senior Policy Advisor Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM) 31 Safeer Quraishi Administrative Director Public Policy and Civil Rights Advocacy New Jersey State Conference National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) 37 TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued) Page Bishop Jethro C. James, Jr. Senior Pastor Paradise Baptist Church, and President Newark/North Jersey Committee of Black Churchmen, and Chaplain New Jersey State Police, and Senior Advisor New Jersey Responsible Approaches to Marijuana Policy (NJ RAMP) 41 Jaleel Terrell Policy Advocate New Jersey Parents’ Caucus 46 Pamela Capaci Executive Director Prevention Links 46 Reverend George E. -

Ella Fitzgerald Collection of Sheet Music, 1897-1991

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2p300477 No online items Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music, 1897-1991 Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Bucher, Melissa Haley, Doug Johnson, 2015; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] ©2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet PASC-M 135 1 music, 1897-1991 Title: Ella Fitzgerald collection of sheet music Collection number: PASC-M 135 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 13.0 linear ft.(32 flat boxes and 1 1/2 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1897-1991 Abstract: This collection consists of primarily of published sheet music collected by singer Ella Fitzgerald. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. creator: Fitzgerald, Ella Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

PDF Download Lawman Pdf Free Download

LAWMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Diana Palmer | 362 pages | 01 May 2008 | Harlequin (UK) | 9780373772834 | English | Richmond, United Kingdom Lawman () - IMDb Name that government! Or something like that. Can you spell these 10 commonly misspelled words? Do you know the person or title these quotes desc Login or Register. Save Word. Definition of lawman. Synonyms Example Sentences Learn More about lawman. Keep scrolling for more. Synonyms for lawman Synonyms bobby [ British ], bull [ slang ], constable [ chiefly British ], cop , copper , flatfoot [ slang ], fuzz , gendarme , officer , police officer , policeman , shamus [ slang ] Visit the Thesaurus for More. Recent Examples on the Web Since winning the lottery nearly two decades ago, Chody has built a reputation as a conservative lawman with a penchant for social media and a craving for celebrity. First Known Use of lawman , in the meaning defined above. Learn More about lawman. Time Traveler for lawman The first known use of lawman was in See more words from the same year. As the film goes along we tend to dislike him more, and feel sorry for Lee. Cobb, Robert Duvall and some other cowboys. Sheree North is the woman who was once beautiful, but now looks worn out by age and hard life. Robert Ryan, always a great presence, is the man who is tired of having to prove his courage in gunfights and thinks he deserves a quiet, more stable life. Looking for some great streaming picks? Check out some of the IMDb editors' favorites movies and shows to round out your Watchlist. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. -

Cowboy Way Jubilee

eryt ng Ev hing ati Cow br b le o e y C A Cowboy Way Jubilee P re reser Cultu ving Cowboy ATribune Triannual Publication, Oleeta Jean, LLC, Publisher VOLUME 3, ISSUE 1—SUMMER 2020 Celebrating Everything Cowboy—New & Old! Event Sponsors The Cowboy Way Code — Meet George Stamos TO BECOME A SPONSOR, CALL LESLEI 580.768.5559 FORT CONCHO Charlene & George Stamos with Leslei Fisher & Gene Ford @ the 2017 National Rodeo Finals, Las Vegas, Nevada THE COWBOY WAY, Code, Creed, Rules who was in the wrong, would say, “oh gosh, to Live By, Ethics, whatever you want to yes! I broke the code. I am sorry!” and gen- call it, is a set of rules or guidelines around uinely mean it. These codes mattered to us. which one attempts to fashion his life. Our Heros followed them, they certainly There are many ‘sets’ of these rules. appeared to whenever they were in public, • Roy Rogers’ Riders Rules so we were religious about following them • Gene Autry’s Cowboy Code as well. • Hopalong Cassidy’s Creed for Boys I can recall more than once an argument and Girls breaking out amongst the kids on the play- • The Lone Ranger’s Creed ground as to WHO’S code was THE ONE. And at least a dozen more. Those of us Gene’s or Roy’s or Hoppy’s or the Lone born in the 1940s to 1960s grew up on Ranger’s or… but since all the codes were these codes of conduct. They were import- very similar we simply agreed to disagree.