Seed Security Assessment– Lesotho 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senior Softball World Championships 2020 St

Senior Softball World Championships 2020 St. George, Utah September 17 - 19, 2020 Rev. 08/28/2020 Men's 60+ Major Plus Division • 4 Teams Win Loss 3 0 1 LPC 60's/Dudley (CA) 122Omega IT Services, LLC (VA) 0 3 3 Samurai (CA) 2 1 4 Texas Crush Sixties Thursday • September 17, 2020 • The Canyons Softball Complex • St. George Field address ► 1890 West 2000 North - St George, UT 84770 Time # Runs Team Name Field # Runs Team Name 9:30 AM 317 Samurai (CA) 2132 LPC 60's/Dudley (CA) 11:00 AM 220 Omega IT Services, LLC (VA) 2426 Texas Crush Sixties 12:30 PM 423 Texas Crush Sixties 23 7 Samurai (CA) USA NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIP GAME • LPC 60's/Dudley (West) vs. Omega IT Services, LLC (East) 2:00 PM 124 LPC 60's/Dudley (CA) 22 8 Omega IT Services, LLC (VA) Friday • September 18, 2020 • The Canyons Softball Complex • St. George Time # Runs Team Name Field # Runs Team Name 12:30 PM 226 Omega IT Services, LLC (VA) 6311 Samurai (CA) 12:30 PM 130 LPC 60's/Dudley (CA) 7429 Texas Crush Sixties Seeding for 60-Major Plus Double Elimination bracket commencing Friday afternoon • See bracket for details Format: Full (3-game) Round Robin to seed 60-Major+ Double Elimination bracket Home Runs - Major+ = 9 per team per game, Outs NOTE SSUSA Official Rulebook §9.5 (Retrieving Home Run Balls) will be strictly enforced. Pitch Count - All batters start with 1-1 count (WITH courtesy foul) per SSUSA Rulebook §6.2 (Pitch Count) Run Rules - 7 runs per ½ inning at bat (except open inning) Time Limits - RR = 65 + open inn. -

Lesotho 2019 Human Rights Report

LESOTHO 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lesotho is a constitutional monarchy with a democratic parliamentary government. Under the constitution the king is head of state but does not actively participate in political activities. The prime minister is head of government and has executive authority. In 2017 former prime minister Pakalitha Mosisili of the Democratic Congress Party lost a vote of no confidence and a snap election. All major parties accepted the outcome, and Motsoahae Thomas Thabane of the All Basotho Convention Party (ABC) formed a coalition government and became prime minister. Mosisili transferred power peacefully to Thabane, and Mathibeli Mokhothu assumed leadership of the opposition. Local and international observers assessed the election as peaceful, credible, and transparent. The security forces consist of the Lesotho Defense Force (LDF), the Lesotho Mounted Police Service (LMPS), the National Security Service (NSS), and the Lesotho Correctional Service (LCS). The LMPS is responsible for internal security. The LDF maintains external security and may support police when the LMPS commissioner requests assistance. The NSS is an intelligence service that provides information on possible threats to internal and external security. The LDF and NSS report to the minister of defense; the LMPS, to the minister of police and public safety; and the LCS, to the minister of justice and correctional service. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) Preventive Mission in Lesotho contingent of troops, deployed to foster stability as the government moved forward with SADC-recommended security-sector reforms, departed the country in November 2018. In May the government did not meet an SADC deadline for completion of constitutional and security reforms. -

Private Solutions for Infrastructure in Lesotho

A COUNTRY FRAMEWORK REPORT Private Solutions for Infrastructure in Lesotho PUBLIC-PRIVATE INFRASTRUCTURE ADVISORY FACILITY THE WORLD BANK A Country Framework Report Private Solutions for Infrastructure in Lesotho THE WORLD BANK Washington, D.C. Copyright © 2004 The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ this report are entirely those of the authors and should not be THE WORLD BANK attributed in any manner to the Public-Private Infrastructure 1818 H Street,NW Advisory Facility (PPIAF) or to the World Bank, to its affil- Washington, DC 20433, USA iated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Telephone 202-473-1000 Directors or the countries they represent. Internet www.worldbank.org Neither PPIAF nor the World Bank guarantees the accu- E-mail [email protected] racy of the data included in this publication or accepts All rights reserved responsibility for any consequence of their use. The bound- Manufactured in the aries, colors, denominations, and other information shown United States of America on any map in this report do not imply on the part of PPIAF or the World Bank Group any judgment on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copyright is held by the World Bank on behalf of both the World Bank and PPIAF. Dissemination of this work is encouraged, and the World Bank will normally grant per- mission promptly and, when reproduction is for non-commercial purposes, without asking a fee. Permission to photocopy portions of this publication should be addressed to: Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, U.S.A., telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, or through the Internet at www.copyright.com For questions about this publication or information about ordering more copies, please refer to the PPIAF web- site or contact PPIAF c/o the World Bank, 1818 H. -

Mohale's Hoek District Council

MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL Information Handbook 2009 Handbook MOHALE’S HOEK DISTRICT COUNCIL LOCAL GOVERNMENT DISTRICT INFORMATION HANDBOOK June 2009 A COMPILATION OF CRUCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE DISTRICT (DISAGGREGATED COUNCIL-WISE) Ministry of local Government and Chieftainship German Technical Cooperation Department of Planning Kingdom of Lesotho Information Handbook 2009 1 handbook contents Prepared by: Department of Planning, Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………….............. 04 Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Mohale’s Hoek District Map………………………………………………………................. 05 Supported by: GTZ Lesotho Introduction………………………………………………………………………...........…….. 06 Background to Local Government in Lesotho……………………………............…………. 07 The Ministry of Local Government and Chieftainship Methodology…………………………………………………………………...........…………. 08 (MOLGC) through its Department of Planning, remains the owner of this handbook. However, there shall be no copy- 1. Profile of Community Councils……………………………………...……………… 09 right restrictions over the use or replication of the whole 2. Social Indicators……………………………………………………...……………… 10 or parts of this handbook. This is an approach for utiliza- 3. Gender Aspects……………………………………………………....………………. 11 tion by the interested parties and is entirely in the public domain. However, no changes shall be made 4. Agriculture………………………………………………………….………………… 12 to the handbook and reprinted thus without prior 5. Trade and Commerce…………………………………………………...…………… 13 permission of MOLGC. 6. Health…………………………………………………………………….…………… -

Naturments.Com Naturments 3409 W Oakland Park Blvd, Lauderdale Lakes, Florida 33311

United States of America FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION Southwest Region Dama J. Brown, Regional Director Federal Trade Commission – Southwest Region 1999 Bryan Street, Suite 2150 Dallas, Texas 75201 May 1, 2020 WARNING LETTER Via U.S. Mail and email: [email protected] Naturments 3409 W Oakland Park Blvd, Lauderdale Lakes, Florida 33311 Re: Unsubstantiated Claims for Coronavirus Prevention and Treatment To Whom It May Concern: This is to advise you that FTC staff has reviewed your website at https://www.naturments.com on April 29, 2020. We have determined that you are unlawfully advertising that certain products prevent or treat Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Some examples of Coronavirus prevention or treatment claims on your website include the following representations made concerning Black Seed Oil: On a webpage titled “Fight Coronavirus with Black Seed Oil: Boost Your Immunity,” under the heading “Research to Combat Coronavirus That Used Nigella Sativa Extracts,” you claim: “In an attempt to prevent COVID-19 duplication and possibly kill it, a study was made where it was found that extracts of Anthemis hyalina (Ah), Nigella sativa (Ns) and peels of Citrus sinensis (Cs) which were earlier used as a traditional medicine to combat antimicrobial diseases could decrease the virus load when any of them were added to the coronavirus infected cells. In the study, they tested the extracts based on their effectiveness on the imitation of coronavirus and the expression of TRP genes during coronavirus infection.” On the same webpage, under the heading “The black seed oil contains antiviral and antibacterial effects,” you claim: “Nigella sativa contains many essential components one of which is thymoquinone, an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory compound. -

Mcc Lesotho Compact 2008-2013 Evaluation Design

MCC LESOTHO COMPACT 2008-2013 MCA HEALTH PROJECT LESOTHO FINAL EVALUATION MCC-15-PO-0074 EVALUATION DESIGN June 16, 2017 HEALTHMATCH consultancies Pim de Graaf The Netherlands Page 1 of 96 Content CONTENT .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................... 4 I INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................ 5 COUNTRY CONTEXT .................................................................................................................................................. 5 HEALTH PROFILE ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 HEALTH SYSTEM ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 OBJECTIVES OF THIS REPORT .................................................................................................................................... 12 2 OVERVIEW OF THE COMPACT ................................................................................................................ 13 THE HEALTH PROJECT AND IMPLEMENTATION PLAN ...................................................................................................... -

Seed Journal APRIL 2019 Newsletter of the North Dakota State Seed Department

The North Dakota Seed Journal APRIL 2019 Newsletter of the North Dakota State Seed Department Preparing for Field Inspection Inside Joe Magnusson, Field Seed Program Manager Plant eligible seed on eligible ground 1 Preparing for Field Inspection Seed cannot be planted on fields that had the same crop the previous year unless 2 From the Commisioner’s it was the same variety and that field was inspected for certification. Durum has an Desk additional restriction, which prohibits planting Foundation class seed on fields that 3 Summer Field Days had spring wheat the previous two years. If you plant Registered durum seed, one year out of spring wheat is all that is required. Even so, we recommend avoiding 3 Seed industry plays important spring wheat ground for several years as we have seen wheat carryover and role in controlling Palmer volunteer in some fields for up to five years. Though it is not recommended, you can amaranth plant crops on land which we consider inseparable (small grain crops on previous 4 The Importance of small grain residue) the following year with the exception of durum on wheat as Completing Forms stated above. If this is your only planting option, monitor the field for volunteer crops 4 Germination and TZ testing before the inspector arrives and if you notice patches of other crop plants, you can cancel the field prior to inspection. Some crop admixtures (wheat, barley and oats) 5 Potato Virus Y and North if carefully conditioned, can be removed from the seed lot and may pass the final Dakota certification process. -

Highlights Contents

LESOTHO METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES (LEKALA LA TSA BOLEPI) Ten-Day Agrometeorological Bulletin 21st – 31st January 2005 Issue No.10/2004-05 Date of Issue: 4 February 2005 Vol. 3 …dedicated to the agricultural community … aimed at harmonizing agricultural activities with weather and climate Contents Highlights Weather Summary Page 1 q Below normal rains recorded. Rainfall Situation q Cumulative rainfall normal countrywide. Page 1 q Temperature Crops conditions good at few localities. Page 1 q Infestation of insects at some places. Crop Stage and Condition Page 1 q Low rainfall expected for next dekad. Dekadal Outlook Page 1 Rainfall and Temperature Summaries Page 2 Glossary Page 3 The Director TEL: (+266) 22324374/22324425 Lesotho Meteorological Services FAX: (+266) 22325057/22350325 Agrometeorological Section E-mail:[email protected] P.O. Box 14515 http://www.lesmet.org.ls Maseru 100, Lesotho Issue No. 10/2004-05 Vol.3 21st –31st January 2005 WEATHER SUMMARY The percentage departure from normal cumulative 11th – 20 th January 2005 rainfall ranges from -12% to 32% (Table 1). The highest cumulative rainfalls of 721.5mm, The last dekad of January was dominated by 543.9mm and 509.4mm are recorded at Oxbow, surface trough. However, there was insufficient Leribe and Qacha’s Nek (Table 1 and Fig. 3). moisture over the interior as a result only partly Mafeteng, Maseru Airport, Moshoeshoe I and cloudy and warm conditions with few Phuthiatsana stations are the only stations which thundershowers occurred. have received cumulative rainfall of less than 400mm. RAINFALL SITUATION TEMPERATURE The last ten days of January received relatively low rainfall compared to the previous dekad (11th th The country experienced near normal – 20 January 2005) which was very wet. -

An Archaeology of Walls in the Walking Dead

Undead Divides: An Archaeology of Walls in The Walking Dead Howard Williams In 2010, the zombie horror genre gained even greater popularity than the huge following it had previously enjoyed when AMC’s The Walking Dead (TWD) first aired. The chapter surveys the archaeology of this fictional post-apocalyptic material world in the show’s seasons 1–9, focusing on its mural practices and environments which draw upon ancient, biblical, medieval and colonial motifs. The study identifies the moralities and socialities of wall-building, dividing not only survivors aspiring to re-found civilization from the wilderness and manifesting the distinctive identities of each mural community, but also distinguishing the living from the undead. The roles of the dead and the undead in mural iterations are also explored. As such, dimensions of past and present wall-building practices are reflected and inverted in this fictional world. As part of a broader ‘archaeology of The Walking Dead’, the chapter identifies the potentials of exploring the show’s physical barriers within the context of the public archaeology of frontiers and borderlands. Andrea: What’s your secret? The Governor: Really big walls. Andrea: That soldier had walls too and we all know how that turned out, so. The Governor: I guess we do. The real secret is what goes on within these walls. It’s about getting back to who we were, who we really are, not just waiting to be saved. You know people here have homes, medical care, kids go to school. Adults have jobs to do. It’s a sense of purpose. -

Talking About Dying: How to Begin Honest Conversations About What Lies Ahead October 2018

Talking about dying: How to begin honest conversations about what lies ahead October 2018 0QR_0092_OFH_EoL_report.indd 1 26/09/2018 13:29 Talking about dying October 2018 Our Future Health In its 500th year, the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) is taking the opportunity to reflect on day- to-day dilemmas facing physicians and patients within the current healthcare system. Our Future Health is a year-long campaign of events and multimedia outputs that will lead the debate and raise awareness of the impact of these challenges on patients, healthcare professionals and the NHS. This campaign has focused on three main areas: clinical resources, innovation and research, and investment. The data captured are informing policy positions and documents that will drive improvement in health and healthcare through advocacy, education and research. Authors Join in the discussion Dr Sarah-Jane Bailey National medical director’s clinical fellow 2017/18 #OurFutureHealth @RCPFuture ST6 in geriatrics and general internal medicine Kacey Cogle Policy projects and engagement manager Royal College of Physicians Case studies kindly provided by: Tess Makinson, end of life care facilitator, Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust Helen Meehan, lead nurse – palliative care and end of life Rachel Davis, senior clinical nurse specialist – palliative care, Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust Victoria McLoughlin, palliative and end of life care practice development lead Marie Roberts and Anne Mitchell, lead clinical facilitators for supportive palliative care for care homes, Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust Dr Karen Forbes, professorial teaching fellow and consultant in palliative medicine, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust Acknowledgements This report could not have been developed without the support of: Professor Dame Jane Dacre Professor Bee Wee Professor David Oliver Professor Andrew Goddard RCP Joint Specialist Committee for Palliative Care Professor Derek Willis Professor Rob George. -

Team Standings

TEAM STANDINGS Team standings for: 07-12-16 Yost Team Name Division rank Score !Fun Must Be Always! Yost 1 100 Team McEwen Yost 2 97.71875 Sufferin' Succotash, Mach II Yost 3 85.8515625 mom's on the move Yost 4 85.1451612903225 sMouthies Yost 5 82.9375 Sefcal Yost 6 82.5 Beat Those Buckeyes! Yost 7 71.3125 CLAIRE UNDERWOOD IS OUR SPIRIT ANIMAL Yost 8 60.3625 A&B Yost 9 7.28125 Woodson Team Name Division rank Score Donut Attitude Woodson 1 100 PMMS Attack Woodson 1 100 Ironladiez Woodson 1 100 International Powerhouse Woodson 2 99.1125 Re-boot Camp Woodson 3 94.3611111111111 IntrEpid Woodson 4 94.171875 Milk Room Movers and Shakers Woodson 5 92.40625 UMOR Moves More Woodson 6 87.9479166666666 Bo Knows Transplant Woodson 7 76.516129032258 Energetic Devoted Resourceful Evolved Go-Getters Woodson 8 76.2278481012658 get MOTTivated.ORg Woodson 9 64.4368421052631 Woodson Team Name Division rank Score CTO McSlims Woodson 10 64.3125 U of M Radiology Woodson 11 54.7421875 Materiel Services Faith Walkers Woodson 12 54.6875 Wolverines Division Team Name Division rank Score The Banana Boys Wolverines Division 1 100 Let's do all the running! Wolverines Division 1 100 The M Team Wolverines Division 1 100 VJPB Wolverines Division 2 99.875 Angell Walkers Wolverines Division 3 99.5769230769231 Healthy for U Wolverines Division 4 99.2291666666666 Agony of DeFeet Wolverines Division 5 97.974358974359 Wolverines Division Team Name Division rank Score Balance, Movement, Energy Wolverines Division 6 97.9166666666666 Citrusmilo Canyon Crunchers Wolverines Division -

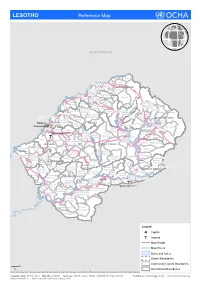

LESOTHO Reference Map

LESOTHO Reference Map SOUTH AFRICA Makhunoane Liqobong Likila Ntelle n Maisa-Phoka Ts'a-le- o d Moleka le BUTHA BUTHE a Lipelaneng C Nqechane/ Moteng Sephokong Linakeng Maputsoe Leribe Menkhoaneng Sekhobe Litjotjela Likhotola/ LERIBE Hleoheng Malaoaneng Manka/ Likhakeng Matlameng Mapholaneng/ Fobane Koeneng/ Phuthiatsana Kolojane Lipetu/ Kao Pae-la-itlhatsoa -Leribe Fenyane Litsilo -Pae-la-itlhatsoa Mokhachane/ Mamathe/Bulara Mphorosane Molika-liko Makhoroana Limamarela Tlhakanyu/Motsitseng Teyateyaneng Seshote Mapholaneng/ Majoe-Matso/ Meno/ Lekokoaneng/Maqhaka Mohatlane/ Sebetia/Khokhoba Pae-la-itlhatsoa Matsoku -Mapholaneng MOKHOTLONG Lipohong Thuapa-Kubu/ Moremoholo/ Katse Popa Senekane BEREA Moshemong Maseru Thuathe Koali/ Taung/Khubelu Mejametalana p Mokhameleli Semenanyane Mokhotlong S Maluba-lube/ Mateanong e Maseru Suoane/ m Rafolatsane Thaba-Bosiu g Ratau e Liphakoeng n Bokong n e a Ihlo-Letso/ Mazenod Maseru Moshoeshoe l Setibing/ Khotso-Ntso Sehong-hong e Tsoelike/ Moeketsane h Pontseng/ Makopoi/ k Mantsonyane Bobete p Popa_MSU a Likalaneng Mahlong Linakaneng M Thaba-Tseka/ Rothe Mofoka Nyakosoba/Makhaleng Maboloka Linakeng/Bokhoasa/Manamaneng THABA TSEKA Kolo/ MASERU Setleketseng/ Tebang/ Matsieng Tsakholo/Mapotu Seroeneg S Mashai e Boleka n Tsa-Kholo Ramabanta/ q Methalaneng/ Tajane Moeaneng u Rapo-le-boea n Khutlo-se-metsi Litsoeneng/Qalabane Maboloka/ y Sehonghong Thaba-Tsoeu/ Monyake a Lesobeng/ Mohlanapeng Mathebe/ n Sehlaba-thebe/ Thabaneng Ribaneng e Takalatsa Likhoele Moshebi/ Kokome/ MAFETENG Semonkong Leseling/