Frank Stella's Decline: on the Artist's Whitney Museum Retrospective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Hollis Frampton. Untitled [Frank Stella]. 1960](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3709/hollis-frampton-untitled-frank-stella-1960-243709.webp)

Hollis Frampton. Untitled [Frank Stella]. 1960

Hollis Frampton. Untitled [Frank Stella]. 1960. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California (930100). Courtesy Barbara Rose. © Estate of Hollis Frampton. Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/octo.2007.119.1.94 by guest on 30 September 2021 “Frank Stella is a Constructivist”* MARIA GOUGH No matter what we say, we are always talking about ourselves. —Carl Andre (2005) I begin with a photograph taken in 1960 by the photographer and soon-to- be filmmaker Hollis Frampton in the West Broadway studio of his friend Frank Stella.1 The painter’s upturned head rests against the window sill, almost decapi- tated. Defamiliarizing his physiognomy, the camera relocates his ears below his chin, trunking his neck with its foreshortening. Arrested, his eyes appear nervous, jumpy. On the sill sits a sculpture by Frampton and Stella’s mutual friend Carl Andre, Timber Spool Exercise (1959), a weathered stump of painted lumber, its midriff cut away on all four sides. This giant spool was one of dozens of such exer- cises that Andre produced in summer 1959 with the help of a radial-arm saw in his father’s toolshed in Quincy, Massachusetts, a few examples of which he brought back to New York. Propped atop it is a small mirror, angled to reflect the jog of Union Pacific (1960), a twelve-foot-long aluminum oil painting that leans against the opposite wall of the studio, its two lower corners and upper middle cut away, itself a mirror-image duplication of the square-format Kingsbury Run (1960) of the same series. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

DARBY BANNARD Born New Haven, CT Education Princeton University

DARBY BANNARD Born New Haven, CT Education Princeton University Solo Exhibitions 2012 Lowe Art Museum, Coral Gables, FL 2011 Galerie Konzette, Vienna, Austria Taubman Museum, Roanoke, Virginia Loretta Howard Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Center for Visual Communication, Miami, FL Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2009 Center for Visual Communication, Miami, FL 2007 Jacobson/Howard Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Rauschenberg Gallery, Edison College, Fort Meyers, FL Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI 2002 The 1912 Gallery, Emory and Henry College, Emory, VA 1999 Lowe Art Museum, Coral Gables, FL 1997 Lee Scarfone Gallery, University of Tampa, Tampa, FL 1996 Dorsch Gallery, Miami, FL 1993 Farah Damji Gallery, New York, NY 1992 Jaffe Baker Gallery, Boca Raton, FL Jaffe Baker Gallery, Boca Raton, FL 1991 Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair, NJ Knoedler Gallery, London 1990 Greenberg/Wilson Gallery, New York, NY Ann Jaffe Gallery, Miami, FL Miami-Dade Community College, Miami, FL 1989 Greenberg Wilson Gallery, New York, NY Rider College Art Gallery, Lawrenceville, NJ 1988 Richard Love Gallery, Chicago, IL 1987 Brush Art Gallery, St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY 1986 Princeton Country Day School, Princeton, NJ Salander-O’Reilly Gallery, New York, NY Solo Exhibitions (cont’d): 1984 Knoedler Gallery, London Watson/de Nagy, Houston, TX 1983 Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC Martin Gerard Gallery, Edmonton, Alberta, BC Edmonton Art Gallery, Edmonton, Alberta, BC 1982 Martin Gerard Gallery, Edmonton, Alberta, BC Knoedler Gallery, London Watson/de -

Shifting Momentum: Abstract Art from the Noyes Collection

Education Guide April 5 – June 6, 2018 Shifting Momentum: Abstract Art from the Noyes Collection Free Opening Reception: Second Friday, April 13, 2018 6:00 – 8:00 pm Curator’s Talk by Chung-Fan Chang: 6:00pm This show features abstract works by Dimitri Petrov, Lucy Glick, Robert Natkin, Jim Leuders, W.D. Bannard, Robert Motherwell, Frieda Dzubas, Alexander Liberman, David Johnston, Hulda Robbins, Wolf Kahn, Deborah Enight, Oscar Magnan, and Katinka Mann. Lucy Glick, Quiet Landing, oil on linen, 1986 Dimitri Petrov was born in Philadelphia in 1919, grew up in an anarchist colony in New Jersey and spent much of his career in Philadelphia. In 1977, he moved to Mount Washington, Massachusetts. Petrov later attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and studied printmaking with Stanley Hayter at the Atelier 17 Workshop. He was a member of the Dada movement and a Surrealist painter and printmaker. He was also the editor of a surrealist newspaper, Instead, a member of the Woodstock Artists Association, and editor/publisher of publications including the “Prospero” series of poet-artist books "Letter Edged in Black". Lucy Glick, an artist whose vividly colored paintings were known for their bold lines and sense of movement was born in Philadelphia. Glick attended the Philadelphia College of Art from 1941 to 1943 and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1958 to 1962. Her paintings were a vehicle for expressing her emotions, usually with strong lines, energetic brush strokes and a luminous quality. Robert Natkin was born in Chicago in 1930 into a large Russian-Jewish immigrant family. -

Minimalism 1 Minimalism

Minimalism 1 Minimalism Minimalism describes movements in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, where the work is stripped down to its most fundamental features. As a specific movement in the arts it is identified with developments in post–World War II Western Art, most strongly with American visual arts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Prominent artists associated with this movement include Donald Judd, John McLaughlin, Agnes Martin, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Anne Truitt, and Frank Stella. It is rooted in the reductive aspects of Modernism, and is often interpreted as a reaction against Abstract expressionism and a bridge to Postmodern art practices. The terms have expanded to encompass a movement in music which features repetition and iteration, as in the compositions of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, and John Adams. Minimalist compositions are sometimes known as systems music. (See also Postminimalism). The term "minimalist" is often applied colloquially to designate anything which is spare or stripped to its essentials. It has also been used to describe the plays and novels of Samuel Beckett, the films of Robert Bresson, the stories of Raymond Carver, and even the automobile designs of Colin Chapman. The word was first used in English in the early 20th century to describe the Mensheviks.[1] Minimalist design The term minimalism is also used to describe a trend in design and architecture where in the subject is reduced to its necessary elements. Minimalist design has been highly influenced by Japanese traditional design and architecture. In addition, the work of De Stijl artists is a major source of reference for this kind of work. -

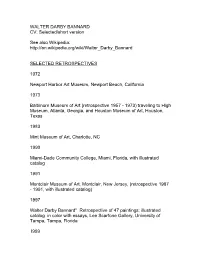

DARBY BANNARD CV: Selected/Short Version

WALTER DARBY BANNARD CV: Selected/short version See also Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Darby_Bannard SELECTED RETROSPECTIVES 1972 Newport Harbor Art Museum, Newport Beach, California 1973 Baltimore Museum of Art (retrospective 1957 - 1973) traveling to High Museum, Atlanta, Georgia, and Houston Museum of Art, Houston, Texas 1983 Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC 1990 Miami-Dade Community College, Miami, Florida, with illustrated catalog 1991 Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair, New Jersey, (retrospective 1987 - 1991, with illustrated catalog) 1997 Walter Darby Bannard" Retrospective of 47 paintings; illustrated catalog in color with essays, Lee Scarfone Gallery, University of Tampa, Tampa, Florida l999 “Darby Bannard: Paintings l987-l999” Rretrospective of 44 paintings, Ill. Catalog in color with essays, Lowe Art Museum, Coral Gables, FL 2002 Darby Bannard: Recent Acrylic Paintings and Oilstick/MM Paintings of the 1990s” Emory & Henry College, Emory, Virginia 2006 "Moving into Color: Paintings by Darby Bannard", Rauschenberg Gallery, Edison College, Ft. Myers, FL 2009 "Darby Bannard, The Miami Years, Then and Now: A retrospective exhibit of 20 years of Painting” Center for Visual Communication, Miami, Florida ================================================ SELECTED ONE-MAN EXHIBITIONS Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York 1965-1970 Kasmin Gallery, London 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972 Richard Feigen Gallery, Chicago 1965 Nicholas Wilder Gallery, Los Angeles, 1967 Bennington College 1969 David Mirvish Gallery, Toronto 1969, 1970, 1975, 1978 Lawrence Rubin Gallery, New York 1970, 1972, 1973 Joseph Helman Gallery, St. Louis 1970 Neuendorf Gallery, Cologne, Germany 1971 Newport Harbor Art Museum, Newport Beach, California, 1972 Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA, 1973 Knoedler Contemporary Art, New York 1974-1984 Lamont Gallery, Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, NH 1977 Greenberg Gallery, St. -

Phd, Art & Archaeology, Princeton University

ALEX BACON [email protected] EDUCATION 2021 [anticipated] PhD, Art & Archaeology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ • Dissertation: “ ‘Frank Stella and a Crisis of Nothingness’: The Emergence of Object Art in America, 1958-1967” 2009 MA, Art & Archaeology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 2007 BA, with Highest Honors, History of Art, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI • Thesis: “Punks, Skinheads, and Dandies: Matrices of Desire in Gilbert & George” CURRENT ACTIVITIES 2017 - PRESENT Contributing Writer, Artforum.com • Critic’s Picks and 500 Word statements by artists including Carmen Herrera and Doug Wheeler 2012 - PRESENT Contributing Writer, The Brooklyn Rail • Numerous long form artist interviews for the Brooklyn Rail, including Mary Corse, Francesco Clemente, Mary Heilman, and James Turrell. Also reviews and feature articles. 2012 - PRESENT Ad Reinhardt Catalogue Raisonné Project • Ad Reinhardt Foundation. First volume, on black paintings from the 1960s, anticipated 2022. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE (PAST) 2017 - 2020 Curatorial Associate, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ • Public art commissions around campus. Curator of programming at Bainbridge House, a contemporary art space operated under the aegis of the museum. 2017 Nominating Committee, Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, Artist Awards 2015 - 2017 Nominating Committee, Rema Hort Mann Foundation Emerging Artist Grant 2014 Visiting Critic, AKV/St Joost Academy, Den Bosch, The Netherlands 2014 - 2015 Visiting Critic, Residency Unlimited, Brooklyn, NY 2014 Judge, Wynn Newhouse Awards 2013 Writer-in-Residence, The Miami Rail 2013 Co-founder, with Harrison Tenzer, Curatorial Projects, The Brooklyn Rail 2013 Visiting Critic, Graduate Department of Painting, Rhode Island School of Design 2008 Helena Rubinstein Curatorial Intern, Department of Painting & Sculpture, Museum of Modern Art, New York 2007 Curatorial Intern, Princeton University Art Museum EDITED VOLUMES Editor, with Ellen Blumenstien and Nigel Prince, Channa Horwitz (New York and Vancouver: Circle Books and C.A.G. -

Press Release for Immediate Release Berry

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BERRY CAMPBELL GALLERY PRESENTS ITS FOURTH EXHIBITION OF PAINTINGS BY WALTER DARBY BANNARD NEW YORK, NEW YORK, November 8, 2018 – Berry Campbell Gallery is pleased to announce Walter Darby Bannard: Paintings from 1969 to 1975 featuring seventeen important paintings, including several large-scale canvases that have not been seen since the 1970s. In these rare early works, Bannard used Alkyd resin paints before turning to acrylic gels in 1976. This is Berry Campbell Gallery’s fourth solo exhibition of Walter Darby Bannard since announcing the artist’s representation in 2013. The exhibition will run from November 15 through December 21, 2018 with an opening reception on Thursday, November 15 from 6 to 8 pm. The brochure essay, written by esteemed art historian and curator, Phyllis Tuchman, explores a “look anew at Bannard’s middle period” for the first time in half a century. Tuchman writes: “In a series of dense, speculative essays he began publishing in Artforum in 1966, Bannard focused on pivotal issues he and his fellow abstractionists faced. He was particularly interested in the interaction between color and space. For centuries, when representational art reigned supreme, art historians considered another matter more consequential: the nature of color versus line. But times had changed. Abstract art was ascendant. And, in 1967, Bannard opined: ‘I believe the avant- garde in painting today consists of painters who are dealing with color problems.’ Three years later, he boldly declared: ‘Recently, artists who have been making the very best paintings have been making them in terms of color rather than space.’” A leading figure in the development of Color Field Painting in the late 1950s and an important American abstract painter, Walter Darby Bannard (better known as Darby Bannard) was committed to color-based and expressionist abstraction for over five decades. -

Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power

Minimalism and the Rhetoric ofPower Anna C. Chave et me begin with an anecdote: while I was looking at Don caused the gallery's floor to collapse and had to be removed. The aldJudd's gleaming brass floor box [fig. 1] of 1968 ftom a unapologetic artist described his ambitions for that work in force distance in the galleries of the Museum of Modern Art last ful and nakedly territorial terms: "I wanted very much to seize Spring, two teenage girls strode over to this pristine work, and hold the spac~ that gallery-not simply fill it, but seize kickedL it, and laughed. They then discovered its reflective surface and hold that spac~ore recently, Richard Serra's mammoth, and used it for a while to arrange their hair until, finally, they curving, steel walls have required even the floors of the Castelli bent over to kiss their images on the top of the box. The guard Gallery's industrial loft space to be shored up-which did not near by, watching all of this, said nothing. Why such an object prevent harrowing damage to both life and property,: might elicit both a kick and a kiss, and why a museum guard The Minimalists' E~~[gg:r sometimes ~utah:hetoric might do nothing about it are at issue in this essay. I will argue was breached in this countryln the 1960s, a decact~f brutal that the object's look of absolute, or "plain power," as Judd de displays of power by both the American military in Vietnam, and scribed it, helps explain the' perception that lt dla not need or the police at home in the streets and on university campuses merit protecting, that it could withstand or even deserved such across the country. -

![The Art of the Real USA, 1948-1968 [By] E.C](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7041/the-art-of-the-real-usa-1948-1968-by-e-c-4927041.webp)

The Art of the Real USA, 1948-1968 [By] E.C

The art of the real USA, 1948-1968 [by] E.C. Goossen Author Goossen, E. C Date 1968 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, Conn. Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1911 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE ART OF THE USA 1948-1968 THE ART OF THE REALUSA 1948-1968 E. C. GOOSSEN THE ART OF THE REALUSA 1948-1968 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY NEW YORK GRAPHIC SOCIETY LTD., GREENWICH, CONNECTICUT Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art Lenders to the Exhibition David Rockefeller, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, William S. Lewis Cabot, Helen Webster Feeley, Hollis Frampton, Mr. and Mrs. Victor Paley, and John Hay Whitney, Vice Chairmen; Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, W. Ganz, Henry Geldzahler, Philip Johnson, Donald Judd, Ellsworth President; James Thrall Soby, Ralph F. Colin, and Gardner Cowles, Vice Kelly, Lyman Kipp, Alexander Liberman, Mrs. Barnett Newman, Kenneth Presidents; Willard C. Butcher, Treasurer; Walter Bareiss, Robert R. Noland, Georgia O'Keeffe, Raymond Parker, Betty Parsons, David M. Barker, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss*, William A. M. Burden, Pincus, Steve Shapiro, Seth Siegelaub, Marie-Christophe Thurman, Sam Ivan Chermayeff, Mrs. W. Murray Crane*, John de Menil, Rene d'Harnon- uel J. Wagstaff, Jr., David Whitney, Donald Windham, Sanford Wurmfeld. court, Mrs. C. Douglas Dillon, Mrs. -

Kenneth Noland Selected Publications Bibliography 2018

Kenneth Noland Selected Publications Bibliography 2018 ‘The Joy of Color’, New York: Mnuchin Gallery 2017 William C. Agee, ‘Kenneth Noland: Into the Cool’,New York: Pace Gallery Pernilla Holmes, Amelie von Wedel, Adrienne Edwards et al., ‘IMPULSE’, London: Pace London Michael Danoff, Martin Z. Margulies, Katherine Hinds ‘Martin Z. Margulies Collection, Vol.1’, Bologna BO, Italy: Damiani 2016 William C. Agee ‘Modern Art in America’. London and New York: Phaidon Press Limited Carolina Pasti, ‘A Life with Artists: Hannelore and Rudolph Schulhof’, New York: Skira Rizzoli Publication Rachel Schaefer, Susan Wallach and Katie Woods, ‘The Serial Attitude’, New York: Eykyn Maclean ‘De la peinture (1960-1980)’, Paris: Guttklein fine art - Galerie l’or du temps 2015 Heyler, Joanne, Ed Schad and Chelsea Beck (ed.), ‘The Broad Collection’. Munich, London, New York: Prestel Verlag ‘Hoyland Caro Noland’, London: Pace London 2014 Gwen Allen, David Cateforis and Evelyn C. Hankins, etc., ‘A Family Affair: Modern and Contemporary American Art from the Anderson Collection at Stanford University’, Stanford, California; New York: The Anderson Collection at Stanford University 64 rue de Turenne, 75003 Paris 18 avenue de Matignon, 75008 Paris William C. Agee, ‘Kenneth Noland: Paintings 1975–2003’, New York: Pace Gallery [email protected] - ‘Make it New: Abstract Painting from the National Gallery of Art, 1950–1975’, Abdijstraat 20 rue de l’Abbaye Williamstown: The Clark Art Institute Brussel 1050 Bruxelles [email protected] - ‘Museum -

Press Release for Immediate Release Berry Campbell Gallery Presents an Exhibition of Represented Artists

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE BERRY CAMPBELL GALLERY PRESENTS AN EXHIBITION OF REPRESENTED ARTISTS NEW YORK, NEW YORK, June 20, 2019– Berry Campbell Gallery is pleased to announce its annual exhibition, Summer Selections, a presentation of work from each of the gallery’s represented twenty-eight artists and estates. Also, included in the show will be additional works from the gallery’s inventory by Sam Gilliam, Nancy Graves, Peter Halley, Paul Jenkins, Philip Pavia, and Larry Poons. This exhibition offers a chance to view a wide variety of paintings and works on paper by important mid-century and contemporary artists. Summer Selections will open August 6 and will continue through August 16, 2019. EDWARD AVEDESIAN was born in Lowell, Massachusetts in 1936 and attended the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. After moving to New York City in the early 1960s, he joined the dynamic art scene in Greenwich Village, frequenting the Cedar Tavern on Tenth Street, associating with the critic Clement Greenberg, and joining a new generation of abstract artists, such as Darby Bannard, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, and Larry Poons. Avedisian was among the leading figures to emerge in the New York art world during the 1960s. An artist who mixed the hot colors of Pop Art with the cool, more analytical qualities of Color Field painting, he was instrumental in the exploration of new abstract methods to examine the primacy of optical experience. WALTER DARBY BANNARD, a leader in the development of Color Field Painting in the late 1950s, was committed to color-based and expressionist abstraction for over five decades.