Objecting to Things Megan R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BLACK Baselitz, De Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra

Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com For immediate release BLACK Baselitz, de Kooning, Mariscotti, Motherwell, Serra April 13 – June 3, 2017 Curated by Marcelo Zimmler Spanish Elegy I, Lithograph, on brown HMP handmade paper, 13 3/4 x 30 7/8 in. (35 x 78.5 cm), 1975. Photo by Caius Filimon Upsilon Gallery is pleased to present Black, an exhibition of original and edition work by Georg BaselitZ, Willem de Kooning, Osvaldo Mariscotti, Robert Motherwell and Richard Serra, on view at 146 West 57 Street in New York. Curated by Marcelo Zimmler, the exhibition explores the role played by the color black in Post-war and Contemporary work. In the 1960s, Georg BaselitZ emerged as a pioneer of German Neo–Expressionist painting. His work evokes disquieting subjects rendered feverishly as a means of confronting the realities of the modern age, and explores what it is to be German and a German artist in a postwar world. In the late 1970s his iconic “upside-down” paintings, in which bodies, landscapes, and buildings are inverted within the picture plane ignoring the realities of the physical world, make obvious the artifice of painting. Drawing upon a dynamic and myriad pool of influences, including art of the Mannerist period, African sculptures, and Soviet era illustration art, BaselitZ developed a distinct painting language. Upsilon Gallery 404 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 [email protected] www.upsilongallery.com Willem de Kooning was born on April 24, 1904, into a working class family in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. -

![Hollis Frampton. Untitled [Frank Stella]. 1960](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3709/hollis-frampton-untitled-frank-stella-1960-243709.webp)

Hollis Frampton. Untitled [Frank Stella]. 1960

Hollis Frampton. Untitled [Frank Stella]. 1960. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California (930100). Courtesy Barbara Rose. © Estate of Hollis Frampton. Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/octo.2007.119.1.94 by guest on 30 September 2021 “Frank Stella is a Constructivist”* MARIA GOUGH No matter what we say, we are always talking about ourselves. —Carl Andre (2005) I begin with a photograph taken in 1960 by the photographer and soon-to- be filmmaker Hollis Frampton in the West Broadway studio of his friend Frank Stella.1 The painter’s upturned head rests against the window sill, almost decapi- tated. Defamiliarizing his physiognomy, the camera relocates his ears below his chin, trunking his neck with its foreshortening. Arrested, his eyes appear nervous, jumpy. On the sill sits a sculpture by Frampton and Stella’s mutual friend Carl Andre, Timber Spool Exercise (1959), a weathered stump of painted lumber, its midriff cut away on all four sides. This giant spool was one of dozens of such exer- cises that Andre produced in summer 1959 with the help of a radial-arm saw in his father’s toolshed in Quincy, Massachusetts, a few examples of which he brought back to New York. Propped atop it is a small mirror, angled to reflect the jog of Union Pacific (1960), a twelve-foot-long aluminum oil painting that leans against the opposite wall of the studio, its two lower corners and upper middle cut away, itself a mirror-image duplication of the square-format Kingsbury Run (1960) of the same series. -

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

DARBY BANNARD Born New Haven, CT Education Princeton University

DARBY BANNARD Born New Haven, CT Education Princeton University Solo Exhibitions 2012 Lowe Art Museum, Coral Gables, FL 2011 Galerie Konzette, Vienna, Austria Taubman Museum, Roanoke, Virginia Loretta Howard Gallery, New York, NY 2010 Center for Visual Communication, Miami, FL Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2009 Center for Visual Communication, Miami, FL 2007 Jacobson/Howard Gallery, New York, NY 2006 Rauschenberg Gallery, Edison College, Fort Meyers, FL Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI 2002 The 1912 Gallery, Emory and Henry College, Emory, VA 1999 Lowe Art Museum, Coral Gables, FL 1997 Lee Scarfone Gallery, University of Tampa, Tampa, FL 1996 Dorsch Gallery, Miami, FL 1993 Farah Damji Gallery, New York, NY 1992 Jaffe Baker Gallery, Boca Raton, FL Jaffe Baker Gallery, Boca Raton, FL 1991 Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair, NJ Knoedler Gallery, London 1990 Greenberg/Wilson Gallery, New York, NY Ann Jaffe Gallery, Miami, FL Miami-Dade Community College, Miami, FL 1989 Greenberg Wilson Gallery, New York, NY Rider College Art Gallery, Lawrenceville, NJ 1988 Richard Love Gallery, Chicago, IL 1987 Brush Art Gallery, St. Lawrence University, Canton, NY 1986 Princeton Country Day School, Princeton, NJ Salander-O’Reilly Gallery, New York, NY Solo Exhibitions (cont’d): 1984 Knoedler Gallery, London Watson/de Nagy, Houston, TX 1983 Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC Martin Gerard Gallery, Edmonton, Alberta, BC Edmonton Art Gallery, Edmonton, Alberta, BC 1982 Martin Gerard Gallery, Edmonton, Alberta, BC Knoedler Gallery, London Watson/de -

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015

FY 15 ANNUAL REPORT August 1, 2014- July 31, 2015 1 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report THE PHILLIPS [IS] A MULTIDIMENSIONAL INSTITUTION THAT CRAVES COLOR, CONNECTEDNESS, A PIONEERING SPIRIT, AND PERSONAL EXPERIENCES 2 THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION FY15 Annual Report FROM THE CHAIRMAN AND DIRECTOR This is an incredibly exciting time to be involved with The Phillips Collection. Duncan Phillips had a deep understanding of the “joy-giving, life-enhancing influence” of art, and this connection between art and well-being has always been a driving force. Over the past year, we have continued to push boundaries and forge new paths with that sentiment in mind, from our art acquisitions to our engaging educational programming. Our colorful new visual identity—launched in fall 2014—grew out of the idea of the Phillips as a multidimensional institution, a museum that craves color, connectedness, a pioneering spirit, and personal experiences. Our programming continues to deepen personal conversations with works of art. Art and Wellness: Creative Aging, our collaboration with Iona Senior Services has continued to help participants engage personal memories through conversations and the creating of art. Similarly, our award-winning Contemplation Audio Tour encourages visitors to harness the restorative power of art by deepening their relationship with the art on view. With Duncan Phillips’s philosophies leading the way, we have significantly expanded the collection. The promised gift of 18 American sculptors’ drawings from Trustee Linda Lichtenberg Kaplan, along with the gift of 46 major works by contemporary German and Danish artists from Michael Werner, add significantly to new possibilities that further Phillips’s vision of vital “creative conversations” in our intimate galleries. -

Shifting Momentum: Abstract Art from the Noyes Collection

Education Guide April 5 – June 6, 2018 Shifting Momentum: Abstract Art from the Noyes Collection Free Opening Reception: Second Friday, April 13, 2018 6:00 – 8:00 pm Curator’s Talk by Chung-Fan Chang: 6:00pm This show features abstract works by Dimitri Petrov, Lucy Glick, Robert Natkin, Jim Leuders, W.D. Bannard, Robert Motherwell, Frieda Dzubas, Alexander Liberman, David Johnston, Hulda Robbins, Wolf Kahn, Deborah Enight, Oscar Magnan, and Katinka Mann. Lucy Glick, Quiet Landing, oil on linen, 1986 Dimitri Petrov was born in Philadelphia in 1919, grew up in an anarchist colony in New Jersey and spent much of his career in Philadelphia. In 1977, he moved to Mount Washington, Massachusetts. Petrov later attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and studied printmaking with Stanley Hayter at the Atelier 17 Workshop. He was a member of the Dada movement and a Surrealist painter and printmaker. He was also the editor of a surrealist newspaper, Instead, a member of the Woodstock Artists Association, and editor/publisher of publications including the “Prospero” series of poet-artist books "Letter Edged in Black". Lucy Glick, an artist whose vividly colored paintings were known for their bold lines and sense of movement was born in Philadelphia. Glick attended the Philadelphia College of Art from 1941 to 1943 and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1958 to 1962. Her paintings were a vehicle for expressing her emotions, usually with strong lines, energetic brush strokes and a luminous quality. Robert Natkin was born in Chicago in 1930 into a large Russian-Jewish immigrant family. -

76 Jefferson Fall Penthouse Art Lending Service Exhibition

The Museum of Modern Art U West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart FOR RELEASE: SEPTEMBER 11, 1975 76 JEFFERSON FALL PENTHOUSE ART LENDING SERVICE EXHIBITION 76 JEFFERSON, an exhibition of 38 works produced at that Lower East Side New York address, is the Fall Penthouse exhibition of the Art Lending Service of The Museum of Modern Art, and will be on view from September 11 through December 1. Because of the large number of artists who have lived and worked in the building, the group of works reflects the diversity of art produced in New York 'during the last 15 years. Works by 18 artists in a variety of styles and mediums are included — abstract and realistic painting, sculpture in various materials, and drawings and prints. In addition, there are silkscreen prints published by Chiron Press, which was also located at 76 Jefferson Street from 1963 to 1967. The exhibition has been organized by Richard Marshall, se lections advisor to the Museum's Art Lending Service, and all of the works are for sale. The artists represented in the exhibition who lived and/or worked at 76 Jefferson Street are Milet Andrejevic, E. H. Davis, John Duff, Mel Edwards, Janet Fish, Valerie Jaudon, Neil Jenney, Richard Kalina, Kenneth Kilstrom, Kobashi, Robert Lobe, Brice Marden, Robert Neuwirth, Steve Poleskie, David Robinson, Ed Shostak, Gary Stephan and Neil Williams. The artists whose Chiron Press prints will be on view are Richard Anuskiewicz, Allan d'Arcangelo, Jim Dine, Rosalyn Drexler, Al Held, Robert Indiana, Alex Katz, Ellsworth Kelly, Nicholas Krushenick, Marisol, Robert Motherwell, Louise Nevelson, James Rosenquist, Saul Steinberg, Ernest Trova, Andy Warhol, Jack Youngerman, and Larry Zox. -

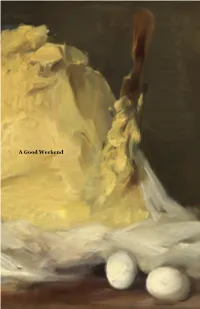

A Good Weekend Cookbook

A Good Weekend A Good Weekend Cookbook Recipes for Various Sweets—and One Potent Cocktail—That Artists Have Created, Utilized, or Simply Enjoyed Over the Past 100 Years Compiled by Andrew Russeth Table of Contents Latifa Echakhch Madeleines au miel 01 Mimi Stone Olive Oil Cake 02 Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec… Rum Punch, Rum Tarte… 04 Mary Cassatt Caramels au Chocolat 06 Norman Rockwell Oatmeal Cookies 07 Grandma Moses Old-Fashioned Macaroons 08 John Cage Almond Cookies 09 Charles Sheeler Shoo-Fly Cake, Molasses Shoo… 10 Roger Nicholson Gunpowder Cake 12 Grant Wood Strawberry Shortcake 13 Karel Appel Cake Barber 15 Sam Francis Schaum Torte 16 Jean Tinguely Omelette Soufflé Dégonflé… 17 Rella Rudoplh Sesame Cookies 18 Frida Kahlo Shortbread Cookies 19 Romare Bearden Bolo Di Rom 20 Richard Estes Aunt Fanny’s English Toffee 22 Alex Katz Sandwich List 23 Robert Motherwell Robert’s Whiskey Cake… 24 Alice Neel Hot-Fudge Sauce 26 George Segal Sponge Cake 27 Tom Wesselmann Banana-Pineapple Bread… 28 An Introduction Since coming across John Cage’s recipe for almond cookies on Greg Allen’s blog a few years ago, I’ve collected recipes associated with artists—dishes they invented, cooked, or just enjoyed—and, much to my surprise, the list has grown quite long. There’s a treasure trove out there! A few examples: Robert Motherwell made rich bittersweet chocolate mousse. Romare Bearden used an old recipe from St. Martin to cook up rum cake. “I don’t do much cooking,” Alice Neel said in 1977. “I’m an artist; I have privileges, you see, that only men had in the past." But she did have a choice recipe for hot-fudge sauce. -

Hartford, Connecticut R EPORT

W ADSWORTH A THENEUM M USEUM OF A RT 2009 A NNUAL R EPORT Hartford, Connecticut R EPORT from the President In 1932, in the midst of the Great Depression, A Everett Austin, Jr. opined that All tenses of time conjoin at the Wadsworth Atheneum, an institution “…the appreciation of works of art serves…to allay for some moments the which continuously honors its historic past, while living in the present and worry and anxiety in which we all share.” It is uplifting to know that over the planning for the future. As we continue to devise both short and long term strate - past twelve months, when the world experienced a challenging financial collapse, gies to preserve our financial stability and enhance the museum’s position as a the gravity of which has not been witnessed since the 1930s, the Wadsworth cultural leader both locally and internationally, we remain fully committed to Atheneum continued as a thriving and stable institution, ensuring that the the constituents who help make our visions a reality through their unwavering lega cy we leave to future generations will be a strong one. support. At the outset of the crisis, the museum implemented swift budgetary To all of the members, friends, patrons, and devotees of this museum— measures in a determined effort to reduce costs. Despite these difficult meas - you have my sincere gratitude. I encourage you to maintain your vital support ures, we remained committed to our artistic mission and to upholding the trust —particularly now, as institutions like ours play a critical role as a place of per - placed in us by our community. -

Fourteen Americans Edited by Dorothy C

Fourteen Americans Edited by Dorothy C. Miller, with statements by the artists and others Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1946 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/3196 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art it iii EFT. fhetxiftt fourteen americans aronson culwell gorky hare maciver motherwell noguchi pereira pickens price roszak sharrer Steinberg tobey fourteen americans EDITED BY DOROTHY C. MILLER with statements by the artists and others THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Copyright 1946. The Museum of Modern Art. Printed in the U.S.A. 4 . ft'l 9 M f) fir contents page FOREWORD 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 9 david aronson 10 ben I. culwell 15 arshile gorky 20 david hare 24 loren maciver 28 robert motherwell 34 isamu noguchi 39 i. rice pereira 44 alt on pickens 49 c. s. price .54 theodore j. roszak 58 honore sharrer 62 said Steinberg 66 mark tobey 70 LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION 76 CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION 76 TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART John Hay Whitney, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, ist Vice-Chairman; Philip L. Goodwin, 2nd Vice-Chairman; Sam A. Lewisohn, yd Vice-Chairman; Nelson A. Rockefeller, President; John E. Abbott, Vice-President and Secretary; Ranald H. Macdonald, Treasurer; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, William A. M. Burden, Stephen C. -

Contact: Karen Frascona Grace Munns 617.369.3442 617.369.3045 [email protected] [email protected]

Maud Morgan Prize – Annette Lemieux, p. 1 Contact: Karen Frascona Grace Munns 617.369.3442 617.369.3045 [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON, AWARDS 2017 MAUD MORGAN PRIZE, HONORING A MASSACHUSETTS WOMAN ARTIST, TO ANNETTE LEMIEUX BOSTON (January 31, 2017)—The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), announced today that Boston-based Annette Lemieux (born 1957) is the recipient of its 2017 Maud Morgan Prize, which honors a Massachusetts woman artist who has demonstrated creativity and vision, and who has made significant contributions to the contemporary arts landscape. Ranging from painting to photography to found-object assemblage, Lemieux’s conceptual works confront urgent subjects such as the horror of war, the nature of time, the elusive truth of memory and the relationship between personal experience and cultural history. Currently a Senior Lecturer on Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard University, she has influenced younger generations of artists as a teacher for more than 20 years. The Museum has collected Lemieux’s works since the late 1980s, cultivating a sustained belief in her practice. As part of the Prize, the artist will receive a $10,000 award, and an exhibition of her work will be Annette Lemieux presented at the MFA in the summer. “Annette is fearless about tackling timely socio-political issues in her artwork. She is a careful observer of the world and a thoughtful commentator on important issues of our time,” said Matthew Teitelbaum, Ann and Graham Gund Director of the MFA. “We look forward to working closely with her and sharing her voice with a wide and appreciative public.” Born in Norfolk, Virginia, Lemieux received a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting from the Hartford Art School, University of Hartford in 1980.