Arxiv:1801.06185V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 18 Jan 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Angular Momentum of Condensations Within Elephant Trunks

A&A 503, 477–482 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200912238 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics The angular momentum of condensations within elephant trunks V. L ora 1,A.C.Raga2, and A. Esquivel2 1 Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ap. 70-468, 04510, D.F México 2 Instituto de Ciencias Nucleares, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ap. 70-543, 04510, D.F México e-mail: [email protected] Received 31 March 2009 / Accepted 22 May 2009 ABSTRACT Aims. The radiation from newly born stars photoevaporates their parental neutral cloud, leading to the formation of dense clumps that will eventually form stars. Methods. We present 3D simulations of the interaction of a neutral cloud with an external ionising radiation field, and compute the angular momenta of these collapsing clumps. Results. The angular momenta of these collapsing clumps show that they have preferential orientations mostly perpendicular to the direction of the incident ionising photon field. Therefore, the axes of the jet systems that will be eventually ejected (from the star+accretion disk systems that will form) will be oriented approximately perpendicular to the direction to the photoionising source. Key words. ISM: kinematics and dynamics – ISM: clouds – ISM: HII regions – stars: formation 1. Introduction of elephant trunks is quite small, their alignment approximately perpendicular to the direction to the ionising photon source The radiation from newly born stars photoionises and erodes the might be indicative of a systematic alignment. This alignment parental cloud, producing structures such as the so-called ele- implies that the angular momenta of the low mass star+disk sys- phant trunks. -

A Spitzer Survey of Protoplanetary Disk Dust in the Young Serpens Cloud: How Do Dust Characteristics Evolve with Time?

The Astrophysical Journal, 714:778–798, 2010 May 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/714/1/778 C 2010. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. A SPITZER SURVEY OF PROTOPLANETARY DISK DUST IN THE YOUNG SERPENS CLOUD: HOW DO DUST CHARACTERISTICS EVOLVE WITH TIME? Isa Oliveira1,2, Klaus M. Pontoppidan2, Bruno Mer´ın3, Ewine F. van Dishoeck1,4, Fred Lahuis1,5, Vincent C. Geers6, Jes K. Jørgensen7, Johan Olofsson8, Jean-Charles Augereau8, and Joanna M. Brown4 1 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, P.O. Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands; [email protected] 2 California Institute of Technology, Division for Geological and Planetary Sciences, MS 150-21, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3 Herschel Science Center, European Space Agency (ESA), P.O. Box 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Canada˜ (Madrid), Spain 4 Max-Planck Institut fur¨ Extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstrasse 1, 85748 Garching, Germany 5 SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, P.O. Box 800, 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands 6 University of Toronto, 50 St. George St., Toronto, ON M5R 2W9, Canada 7 Centre for Star and Planet Formation, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 5-7, DK-1350 Copenhagen, Denmark 8 Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Grenoble, Universite´ Joseph Fourier, CNRS, UMR 5571, Grenoble, France Received 2009 December 28; accepted 2010 March 16; published 2010 April 14 ABSTRACT We present Spitzer InfraRed Spectrograph (IRS) mid-infrared (5–35 μm) spectra of a complete flux-limited sample (3mJyat8μm) of young stellar object (YSO) candidates selected on the basis of their infrared colors in the Serpens Molecular Cloud. -

The Potential to Form Planets in the Orion Nebula ! Rita Mann Plaskett Fellow NRC-Herzberg

The Potential to Form Planets in the Orion Nebula ! Rita Mann Plaskett Fellow NRC-Herzberg ! James Di Francesco, Sean Andrews, Jonathan Williams, Doug Johnstone, John Bally, Meredith Hughes, Luca Ricci, Brenda Matthews Protoplanetary Disks in the Orion Nebula Most stars form in rich clusters Our Solar System formed in a massive star forming environment. To understand planet formation, we need to study disk properties in massive star forming regions! HST images of protostars in Orion Orion Nebula Cluster Trapezium Cluster • Thousands of protostars • Ages ~ 1-2 Myr • Distance ~ 400 pc 1 • θ Ori C, 40M¤, O6 SpT Orion Nebula Cluster Massive Stars • Hostile environment • Many low mass stars near ϑ1C have teardrop shaped morphologies Low Mass Stars PROPLYDS: PROtoPLanetarY DiskS Photoevaporating Proplyds -7 VLA mass-loss rate of 10 M¤/yr Churchwell et al. (1987) Mdisk < 0.1 M¤ Evaporation Timescales < 1 Myr Material removed too quickly! C.R. O’Dell Is planet formation inhibited in rich clusters? Disk Masses in Orion: Previous Attempts Millimeter Wavelength Interferometers (clustered disks) BIMA OVRO PdBI Mundy et al. (1995) Bally et al. (1998) Lada (1999) λ = 3.5 mm λ = 1.3 mm λ = 1.3 mm low sensitivity no detections never published Mdisk ≲ 15 MJUP Radio-Submillimeter SED -0.1 2-4 Ffree-free ~ ν + Fdust ~ ν λ = 1 cm Radio-Submillimeter SED -0.1 2-4 Ffree-free ~ ν + Fdust ~ ν λ = 1 cm 1 mm Radio-Submillimeter SED -0.1 2-4 Ffree-free ~ ν + Fdust ~ ν λ = 1 cm 1 mm Higher frequency observations: more sensitive to dust emission! Interferometry with -

![Arxiv:1610.05765V3 [Astro-Ph.EP] 27 Feb 2017 3.3 Microlensing and Direct Imaging](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5588/arxiv-1610-05765v3-astro-ph-ep-27-feb-2017-3-3-microlensing-and-direct-imaging-1245588.webp)

Arxiv:1610.05765V3 [Astro-Ph.EP] 27 Feb 2017 3.3 Microlensing and Direct Imaging

The Habitability of Planets Orbiting M-dwarf Stars Aomawa L. Shields1;2;4, Sarah Ballard3, John Asher Johnson4 1University of California, Irvine, Department of Physics and Astronomy, 4129 Frederick Reines Hall, Irvine, CA 92697, USA 2University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Box 951547, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 3Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave, 37-241, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 4Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Abstract The prospects for the habitability of M-dwarf planets have long been debated, due to key differences between the unique stellar and planetary environments around these low-mass stars, as compared to hotter, more luminous Sun- like stars. Over the past decade, significant progress has been made by both space- and ground-based observatories to measure the likelihood of small planets to orbit in the habitable zones of M-dwarf stars. We now know that most M dwarfs are hosts to closely-packed planetary systems characterized by a paucity of Jupiter-mass planets and the presence of multiple rocky planets, with roughly a third of these rocky M-dwarf planets orbiting within the habitable zone, where they have the potential to support liquid water on their surfaces. Theoretical studies have also quantified the effect on climate and habitability of the interaction between the spectral energy distribution of M-dwarf stars and the atmospheres and surfaces of their planets. These and other recent results fill in knowledge gaps that existed at the time of the previous overview papers published nearly a decade ago by Tarter et al. -

Transition Disks – Grain Growth, Planets, Or Photoevaporation?

EPJ Web of Conferences 46, 02001 (2013) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/20134602001 © Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2013 Transition Disks – Grain Growth, Planets, or Photoevaporation? T. Birnstiel1;2;a, P. Pinilla3, S. M. Andrews4, M. Benisty5, and B. Ercolano1;2 1University Observatory Munich, Scheinerstr. 1, D-81679 München, Germany 2Excellence Cluster Universe, Technische Universität München, Boltzmannstr. 2, 85748 Garching, Germany 3Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Universität Heidelberg, Albert-Ueberle-Str. 2, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 4Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 5Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG) UMR 5274, Grenoble, F-38041, France Abstract. In the past years, many transition disks have been detected via SED modeling or imaging. The disks feature dust cavities in their inner regions with sizes ranging from a few to more than 70 AU. The origin of those structures, however, remains mysterious. We will present how our recent simulation results, which include gap opening by a giant planet and effects of dust evolution, could explain these structures. 1 Introduction While today’s instruments enable detailed studies of extrasolar planets, their statistics [1–3], or their atmospheres [4–6], their formation occurs hidden in the dense environments of protoplanetary disks. A particular class of protoplanetary disks, the so called transition disks, has been identified through a dip at mid-infrared wavelengths which could be modeled through a dearth of dust in the inner regions [7]. In recent years, (sub-)millimeter imaging has confirmed that these disks have a substantial deficit in their dust surface density in the inner regions [8–17]. -

The Dispersal of Planet-Forming Discs: Theory Confronts Observations Rsos.Royalsocietypublishing.Org Barbara Ercolano1,2, Ilaria Pascucci3,4

The Dispersal of Planet-forming discs: Theory confronts Observations rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org Barbara Ercolano1;2, Ilaria Pascucci3;4 1Universitäts-Sternwarte München, Scheinerstr. 1, Research 81679 München, Germany 2Excellence Cluster Origin and Structure of the Article submitted to journal Universe, Boltzmannstr.2, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany 3Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, The University of Subject Areas: Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA Astrophysics 4Earths in Other Solar Systems Team, NASA Nexus Keywords: for Exoplanet System Science Protoplanetary Disks, Planet Formation Discs of gas and dust around Myr-old stars are a by-product of the star formation process and provide the raw material to form planets. Hence, their Author for correspondence: evolution and dispersal directly impact what type ercolanousm.lmu.de of planets can form and affect the final architecture of planetary systems. Here, we review empirical constraints on disc evolution and dispersal with special emphasis on transition discs, a subset of discs that appear to be caught in the act of clearing out planet-forming material. Along with observations, we summarize theoretical models that build our physical understanding of how discs evolve and disperse and discuss their significance in the context of the formation and evolution of planetary systems. By confronting theoretical predictions with observations, we also identify the most promising areas for future progress. ............ arXiv:1704.00214v2 [astro-ph.EP] 4 Apr 2017 c 2014 The Authors. Published by the Royal Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Abstracts of Talks 1

Abstracts of Talks 1 INVITED AND CONTRIBUTED TALKS (in order of presentation) Milky Way and Magellanic Cloud Surveys for Planetary Nebulae Quentin A. Parker, Macquarie University I will review current major progress in PN surveys in our own Galaxy and the Magellanic clouds whilst giving relevant historical context and background. The recent on-line availability of large-scale wide-field surveys of the Galaxy in several optical and near/mid-infrared passbands has provided unprecedented opportunities to refine selection techniques and eliminate contaminants. This has been coupled with surveys offering improved sensitivity and resolution, permitting more extreme ends of the PN luminosity function to be explored while probing hitherto underrepresented evolutionary states. Known PN in our Galaxy and LMC have been significantly increased over the last few years due primarily to the advent of narrow-band imaging in important nebula lines such as H-alpha, [OIII] and [SIII]. These PNe are generally of lower surface brightness, larger angular extent, in more obscured regions and in later stages of evolution than those in most previous surveys. A more representative PN population for in-depth study is now available, particularly in the LMC where the known distance adds considerable utility for derived PN parameters. Future prospects for Galactic and LMC PN research are briefly highlighted. Local Group Surveys for Planetary Nebulae Laura Magrini, INAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri The Local Group (LG) represents the best environment to study in detail the PN population in a large number of morphological types of galaxies. The closeness of the LG galaxies allows us to investigate the faintest side of the PN luminosity function and to detect PNe also in the less luminous galaxies, the dwarf galaxies, where a small number of them is expected. -

Exoplanet Secondary Atmosphere Loss and Revival 2 3 Edwin S

1 Exoplanet secondary atmosphere loss and revival 2 3 Edwin S. Kite1 & Megan Barnett1 4 1. University of Chicago, Chicago, IL ([email protected]). 5 6 Abstract. 7 8 The next step on the path toward another Earth is to find atmospheres similar to those of 9 Earth and Venus – high-molecular-weight (secondary) atmospheres – on rocky exoplanets. 10 Many rocky exoplanets are born with thick (> 10 kbar) H2-dominated atmospheres but 11 subsequently lose their H2; this process has no known Solar System analog. We study the 12 consequences of early loss of a thick H2 atmosphere for subsequent occurrence of a high- 13 molecular-weight atmosphere using a simple model of atmosphere evolution (including 14 atmosphere loss to space, magma ocean crystallization, and volcanic outgassing). We also 15 calculate atmosphere survival for rocky worlds that start with no H2. Our results imply that 16 most rocky exoplanets interior to the Habitable Zone that were formed with thick H2- 17 dominated atmospheres lack high-molecular-weight atmospheres today. During early 18 magma ocean crystallization, high-molecular-weight species usually do not form long-lived 19 high-molecular-weight atmospheres; instead they are lost to space alongside H2. This early 20 volatile depletion makes it more difficult for later volcanic outgassing to revive the 21 atmosphere. The transition from primary to secondary atmospheres on exoplanets is 22 difficult, especially on planets orbiting M-stars. However, atmospheres should persist on 23 worlds that start with abundant volatiles (waterworlds). Our results imply that in order to 24 find high-molecular-weight atmospheres on warm exoplanets orbiting M-stars, we should 25 target worlds that formed H2-poor, that have anomalously large radii, or which orbit less 26 active stars. -

Protoplanetary Disc Truncation Mechanisms in Stellar Clusters: Comparing External Photoevaporation and Tidal Encounters

MNRAS 000,1{26 (2017) Preprint 9 April 2018 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Protoplanetary disc truncation mechanisms in stellar clusters: comparing external photoevaporation and tidal encounters A. J. Winter1,? C. J. Clarke1, G. Rosotti1, J. Ih2, S. Facchini3, T. J. Haworth4 1Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 2Clare College, Trinity Lane, Cambridge, CB2 1TL 3Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstrasse 1, D-85748 Garching, Germany 4Astrophysics Group, Blackett Laboratory, Imperial College London, Prince Consort Road, London SW7 2AZ, UK Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT Most stars form and spend their early life in regions of enhanced stellar density. There- fore the evolution of protoplanetary discs (PPDs) hosted by such stars are subject to the influence of other members of the cluster. Physically, PPDs might be truncated ei- ther by photoevaporation due to ultraviolet flux from massive stars, or tidal truncation due to close stellar encounters. Here we aim to compare the two effects in real cluster environments. In this vein we first review the properties of well studied stellar clus- ters with a focus on stellar number density, which largely dictates the degree of tidal truncation, and far ultraviolet (FUV) flux, which is indicative of the rate of external photoevaporation. We then review the theoretical PPD truncation radius due to an arbitrary encounter, additionally taking into account the role of eccentric encounters that play a role in hot clusters with a 1D velocity dispersion σv & 2 km/s. Our treat- ment is then applied statistically to varying local environments to establish a canonical 4 −3 threshold for the local stellar density (nc & 10 pc ) for which encounters can play a significant role in shaping the distribution of PPD radii over a timescale ∼ 3 Myr. -

Protoplanetary Disk Masses in NGC 2024: Evidence for Two Populations S.E

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. NGC2024_langedited c ESO 2020 April 29, 2020 Protoplanetary disk masses in NGC 2024: Evidence for two populations S.E. van Terwisga1; 2, E.F. van Dishoeck1; 3, R. K. Mann4, J. Di Francesco4, N. van der Marel4, M. Meyer5, S.M. Andrews6 J. Carpenter7, J.A. Eisner8, C.F. Manara9, and J.P. Williams10 1 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands 2 Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected] 3 Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Gießenbachstraße, D-85741 Garching bei München, Germany 4 NRC Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics, 5071 W Saanich Rd, Victoria BC V9E 2E7, Canada 5 Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, 1085 S. University, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA 6 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 7 Joint ALMA Observatory, Av. Alonso de Córdova 3107, Vitacura, Santiago, Chile 8 Steward Observatory, University of Arizona, 933 North Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 9 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, D-85748 Garching bei München, Germany 10 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa,¯ 2680 Woodlawn Dr., Honolulu, HI, USA April 29, 2020 ABSTRACT Context. Protoplanetary disks in dense, massive star-forming regions are strongly affected by their environment. How this environ- mental impact changes over time is an important constraint on disk evolution and external photoevaporation models. Aims. We characterize the dust emission from 179 disks in the core of the young (0.5 Myr) NGC 2024 cluster. By studying how the disk mass varies within the cluster, and comparing these disks to those in other regions, we aim to determine how external photoevaporation influences disk properties over time. -

Number of Potentially Habitable Planets

universe Article Multiverse Predictions for Habitability: Number of Potentially Habitable Planets McCullen Sandora 1,2 1 Institute of Cosmology, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155, USA; [email protected] 2 Center for Particle Cosmology, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA Received: 14 May 2019; Accepted: 21 June 2019; Published: 25 June 2019 Abstract: How good is our universe at making habitable planets? The answer to this depends on which factors are important for life: Does a planet need to be Earth mass? Does it need to be inside the temperate zone? are systems with hot Jupiters habitable? Here, we adopt different stances on the importance of each of these criteria to determine their effects on the probabilities of measuring the observed values of several physical constants. We find that the presence of planets is a generic feature throughout the multiverse, and for the most part conditioning on their particular properties does not alter our conclusions much. We find conflict with multiverse expectations if planetary size is important and it is found to be uncorrelated with stellar mass, or the mass distribution is too steep. The existence of a temperate circumstellar zone places tight lower bounds on the fine structure constant and electron to proton mass ratio. Keywords: multiverse; habitability; planets 1. Introduction This paper is a continuation of [1], which aims to use our current understanding from a variety of disciplines to estimate the number of observers in a universe Nobs, and track how this depends on the most important microphysical quantities such as the fine structure constant a “ e2{p4pq, the ratio of the electron to proton mass b “ me{mp, and the ratio of the proton mass to the Planck mass g “ mp{Mpl. -

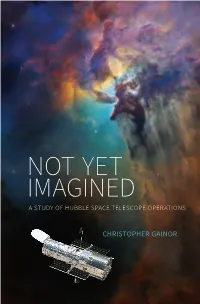

Not Yet Imagined: a Study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations

NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR NOT YET IMAGINED NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2020-4237 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Gainor, Christopher, author. | United States. NASA History Program Office, publisher. Title: Not Yet Imagined : A study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations / Christopher Gainor. Description: Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Communications, NASA History Division, [2020] | Series: NASA history series ; sp-2020-4237 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “Dr. Christopher Gainor’s Not Yet Imagined documents the history of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST) from launch in 1990 through 2020. This is considered a follow-on book to Robert W. Smith’s The Space Telescope: A Study of NASA, Science, Technology, and Politics, which recorded the development history of HST. Dr. Gainor’s book will be suitable for a general audience, while also being scholarly. Highly visible interactions among the general public, astronomers, engineers, govern- ment officials, and members of Congress about HST’s servicing missions by Space Shuttle crews is a central theme of this history book. Beyond the glare of public attention, the evolution of HST becoming a model of supranational cooperation amongst scientists is a second central theme. Third, the decision-making behind the changes in Hubble’s instrument packages on servicing missions is chronicled, along with HST’s contributions to our knowledge about our solar system, our galaxy, and our universe.