Automated Teller Machines: Some Consumer Fees Have Increased

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUTOMATED TELLER MACHINE (Athl) NETWORK EVOLUTION in AMERICAN RETAIL BANKING: WHAT DRIVES IT?

AUTOMATED TELLER MACHINE (AThl) NETWORK EVOLUTION IN AMERICAN RETAIL BANKING: WHAT DRIVES IT? Robert J. Kauffiiian Leollard N.Stern School of Busivless New 'r'osk Universit,y Re\\. %sk, Net.\' York 10003 Mary Beth Tlieisen J,eorr;~rd n'. Stcr~iSchool of B~~sincss New \'orl; University New York, NY 10006 C'e~~terfor Rcseai.clt 011 Irlfor~i~ntion Systclns lnfoornlation Systen~sI)epar%ment 1,eojrarcl K.Stelm Sclrool of' Busir~ess New York ITuiversity Working Paper Series STERN IS-91-2 Center for Digital Economy Research Stem School of Business Working Paper IS-91-02 Center for Digital Economy Research Stem School of Business IVorking Paper IS-91-02 AUTOMATED TELLER MACHINE (ATM) NETWORK EVOLUTION IN AMERICAN RETAIL BANKING: WHAT DRIVES IT? ABSTRACT The organization of automated teller machine (ATM) and electronic banking services in the United States has undergone significant structural changes in the past two or three years that raise questions about the long term prospects for the retail banking industry, the nature of network competition, ATM service pricing, and what role ATMs will play in the development of an interstate banking system. In this paper we investigate ways that banks use ATM services and membership in ATM networks as strategic marketing tools. We also examine how the changes in the size, number, and ownership of ATM networks (from banks or groups of banks to independent operators) have impacted the structure of ATM deployment in the retail banking industry. Finally, we consider how movement toward market saturation is changing how the public values electronic banking services, and what this means for bankers. -

EMF Implementing EMV at The

Implementing EMV®at the ATM: Requirements and Recommendations for the U.S. ATM Community Version 2.0 Date: June 2015 Implementing EMV at the ATM: Requirements and Recommendations for the U.S. ATM Community About the EMV Migration Forum The EMV Migration Forum is a cross-industry body focused on supporting the EMV implementation steps required for global and regional payment networks, issuers, processors, merchants, and consumers to help ensure a successful introduction of more secure EMV chip technology in the United States. The focus of the Forum is to address topics that require some level of industry cooperation and/or coordination to migrate successfully to EMV technology in the United States. For more information on the EMV Migration Forum, please visit http://www.emv- connection.com/emv-migration-forum/. EMV is a trademark owned by EMVCo LLC. Copyright ©2015 EMV Migration Forum and Smart Card Alliance. All rights reserved. The EMV Migration Forum has used best efforts to ensure, but cannot guarantee, that the information described in this document is accurate as of the publication date. The EMV Migration Forum disclaims all warranties as to the accuracy, completeness or adequacy of information in this document. Comments or recommendations for edits or additions to this document should be submitted to: ATM- [email protected]. __________________________________________________________________________________ Page 2 Implementing EMV at the ATM: Requirements and Recommendations for the U.S. ATM Community TABLE OF CONTENTS -

How to Find the Best Credit Card for You

How to find the best credit card for you Why should you shop around? Comparing offers before applying for a credit card helps you find the right card for your needs, and helps make sure you’re not paying higher fees or interest rates than you have to. Consider two credit cards: One carries an 18 percent interest rate, the other 15 percent. If you owed $3,000 on each and could only afford to pay $100 per month, it would cost more and take longer 1. Decide how you plan to pay off the higher-rate card. to use the card The table below shows examples of what it might You may plan to pay off your take to pay off a $3,000 credit card balance, paying balance every month to avoid $100 per month, at two different interest rates. interest charges. But the reality is, many credit card holders don’t. If you already have a credit card, let APR Interest Months history be your guide. If you have carried balances in the past, or think 18% = $1,015 41 you are likely to do so, consider 15% = $783 38 credit cards that have the lowest interest rates. These cards typically do not offer rewards and do not The higher-rate card would cost you an extra charge an annual fee. $232. If you pay only the minimum payment every month, it would cost you even more. If you have consistently paid off your balance every month, then you So, not shopping around could be more expensive may want to focus more on fees and than you think. -

Tourism User Fees

Mobilizing Funding For Biodiversity Conservation: A User-Friendly Training Guide !Go to homepage Tourism User Fees Table of Contents UNDERSTANDING THE MECHANISM – HOW DOES IT WORK ? 2 1.1 Overview 2 1.2 Key Actors and Key Motivations 3 1.2.1 Protected area managers 3 1.2.2 Tourism-related businesses 3 1.2.3 Local communities and local governments 3 1.2.4 Tourists 4 1.3 Types of Tourism User Fees 4 1.3.1 Entrance Fees 4 1.3.2 Concession fees 7 1.3.3 Licenses or Permits 8 1.3.4 Other tourism-related fees and taxes 8 Strengths and Weaknesses of Tourism User Fees 11 1.4 Success Factors 12 1.5 Step-By-Step Methodology 12 2 FEASIBILITY ASSESSMENT PHASE 15 2.1 Overview of feasibility assessment 15 2.2 Generic Terms of Reference (TOR) for feasibility assessment 15 2.2.1 OVERVIEW OF TOR 15 2.3 Generic terms of reference (TOR) for feasibility assessment 16 2.3.1 TERMS OF REFERENCE 16 2.4 Worksheet tools for carrying out feasibility assessment 18 3 IMPLEMENTATION 26 3.1 Bibliographic references 27 3.2 Web sites 28 3.3 Case Study references 29 3.4 Case study summaries 29 Working Draft: We welcome all feedback on format and content 1 Guide_Tourism_Nov2001.doc !TourismGo to home User Feespag e 1 UNDERSTANDING THE MECHANISM – HOW DOES IT WORK ? 1.1 Overview Glossary of Terms Collection mechanism: Logistical Worldwide, tourism is the largest and fastest growing arrangement for collecting user fees industry, with ecotourism as one of the fastest growing (e.g., personnel issuing entrance segments of the market. -

Automated Teller Machine Usage and Customers' Satisfactionin Nigeria

Global Journal of Management and Business Research: C Finance Volume 14 Issue 4 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4588 & Print ISSN: 0975-5853 Automated Teller Machine usage and Customers’ Satisfaction in Nigeria By Odusina, Ayokunle Olumide Abraham Adesanya Polytechnic, Nigeria. Abstract- This paper endeavors to investigate ATM Usage and Customers’ Satisfaction in Nigeria. It was discovered that despite the increasing number of ATM installations in Nigeria. Customers’ needs are not satisfactorily met as customers are always seen on queue in large numbers at various ATM designated centers as well as poor service delivery of some of these machine. The research engages comparative analysis of three banks in Ogun State, Metropolis of Nigeria viz-a- viz First Bank, Guaranty Trust Bank and Skye Bank. However, questionnaires were distributed to the respondents. A total of 200 respondents answered the questionnaire cutting across the three banks, the chi-square statistical tool was used to analyze the data and the results showed a positive and significant relationship between ATM Usage and Customers’ Satisfaction. Keywords: ATM, bank, customers’ satisfaction, nigeria. GJMBR-C Classification : JEL Code: G19 AutomatedTellerMachineusageandCustomersSatisfactioninNigeria Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2014. Odusina, Ayokunle Olumide. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Automated Teller Machine usage and Customers’ Satisfaction in Nigeria Odusina, Ayokunle Olumide Abstract - This paper endeavors to investigate ATM Usage and the available staff on the other hand. -

Health Savings Account Investments

Humana Access Online User Guide Simplify your healthcare finances with convenient, online access to your tax-advantaged spending account 1 Humana Access Contents Getting Started ............................................................................................................................................. 2 HOW TO REGISTER YOUR SPENDING ACCOUNT ..................................................................................... 2 REGISTRATION – STEP 1 ........................................................................................................................... 3 REGISTRATION – STEP 2 ........................................................................................................................... 3 REGISTRATION – STEP 3 ........................................................................................................................... 3 REGISTRATION – STEP 4 ........................................................................................................................... 4 Quick Reference Guide ................................................................................................................................. 5 USING YOUR HUMANA ACCESS MASTERCARD DEBIT CARD .................................................................. 5 CHECKING YOUR ACCOUNT BALANCE(S) ................................................................................................. 7 ACCOUNT TRANSACTIONS ...................................................................................................................... -

Schedule of Fees (PDF)

CAYUGA COUNTY CLERK’S OFFICE Fee Schedule UPDATED April 2021 L a n d R e c o r d i n g : * C o v e r P a g e G e n e r a t e d A u t o m a t i c a l l y - $ 5 . 0 0 F e e Court Filing: Electronic Filing “E-file” Attorneys are required to commence civil actions on the New York State Courts E-filing System, For all case types but the ones listed below: Case Types Exempt from Efiling (paper or electronic filings are acceptable) CPLR Article 70 proceedings CPLR Article 78 proceedings Election Law proceedings Matrimonial matters Mental Hygiene Law matters Hard Copy Filing: PAPER CASE: (Index # is not prefixed by an “E”) Pro-Se Plaintiff / Exempt Case Type / Case started prior to Feb 2021 Original filed Court Documents are retained in the County Clerk’s Office. Send additional copy(s) of your document for Supreme Court and/or your records, include instructions and SASE for returns when filing into a hard copy case. ELECTRONIC CASE: (Index # is prefixed by an “E”) Pro-Se Defendant: drop off or mail in paper filing to clerk’s office. Must include index number on document. Returned Check Fee: $35.00 Current Fee BUILDING LOAN AGREEMENT filing fee $ 25.00 BUILDING LOAN DISCHARGE No fee CERTIFIED COPIES Customer’s copy certified (can only be certified at same time as recording or filing) $ 5.20/+ $5.20 minimum: up to 8 pages included – additional $.65 per page 9+ pages Clerk prepares certified copy $ 5.00/+ $5.00 minimum: up to 4 pages included – additional $1.25 per page 5+ pages CERTIFICATE OF DEPOSIT INTO COURT $ 3.00 CERTIFICATE OF NO EXCEPTION -

All Card Benefits

ALL CARD BENEFITS TRAVEL $200 Airline Fee Credit1 You can receive up to $200 in credits annually for incidental airline fees charged to your Card. Eligible charges include:* • Baggage fees • Flight-change fees • In-flight food and beverage purchases • Airport lounge day passes *American Express relies on accurate airline transaction data to identify incidental fee purchases. If you do not see a credit for a qualifying incidental purchase on your enrolled Card after 4 weeks, simply call the number on the back of the Card. See terms & conditions for more details. Enroll Now> Airport Club Access Program2 Enjoy complimentary lounge access with your Business Platinum Card. Your spouse and children under the age of 21, or up to two companions may enter the club as complimentary guests. Participating lounges include: • American Airlines Admirals Club® • Delta Sky Club® • US Airways® Club – enter regardless of the airline you are flying Find Lounges> Priority Pass™ Select3 Make your international travels more comfortable with worldwide lounge access. • Available at over 600 participating airport lounges in 100 countries • It doesn’t matter what class or airline you fly • Lounge access is complimentary and there’s no fee to enroll • To enter, simply present your Priority Pass Select Card • Guests are charged $27 each Enroll Now> 20% Travel Bonus4 When you use the Pay with Points® program to book all or even part of your trip, you’ll get 20% of the Membership Rewards® points you used credited back to your account. • Book any airline, anywhere, anytime • No seat restrictions or blackout dates Book Now> Global Entry5 Bypass arrival lines at most major U.S. -

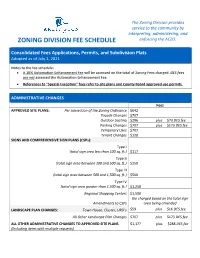

Zoning Division Fee Schedule

The Zoning Division provides service to the community by interpreting, administering, and enforcing the ACZO. ZONING DIVISION FEE SCHEDULE Consolidated Fees Applications, Permits, and Subdivision Plats Adopted as of July 1, 2021 Notes to the fee schedule: • A 10% Automation Enhancement Fee will be assessed on the total of Zoning Fees charged. DES fees are not assessed the Automation Enhancement Fee. • References to “Special Exception” fees refer to site plans and County Board approved use permits. ADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES Fees APPROVED SITE PLANS: Per subsection of the Zoning Ordinance $642 Façade Changes $707 Outdoor Seating $296 plus $73 DES fee Parking Changes $707 plus $173 DES fee Temporary Uses $707 Tenant Changes $120 SIGNS AND COMPREHENSIVE SIGN PLANS (CSPs): Type I (total sign area less than 100 sq. ft.) $117 Type II (total sign area between 100 and 500 sq. ft.) $250 Type III (total sign area between 500 and 1,500 sq. ft.) $500 Type IV (total sign area greater than 1,500 sq. ft.) $1,250 Regional Shopping Centers $1,500 fee charged based on the total sign Amendments to CSPs area being amended LANDSCAPE PLAN CHANGES: Town House, Cluster, URD’s $59 plus $16 DES fee All Other Landscape Plan Changes $707 plus $173 DES fee ALL OTHER ADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES TO APPROVED SITE PLANS $1,177 plus $288 DES fee (Including items with multiple requests) Zoning Fee Schedule p.2 ADMINISTRATIVELY-REVIEWED PERMITS & REQUESTS Fees CONCEPTUAL SITE PLAN $5,945 DANCE HALL PERMIT - ANNUALLY (fee set by statute) $600 LANDSCAPE PLAN (NEW SUBMISSION) $590 plus $318 DES fee HOME OCCUPATION PERMIT $50 ACCESSORY HOMESTAY PERMIT $66 SIGN PERMIT: Permanent or Temporary (up 100 sq. -

Closing Disclosure Document with Your Loan Estimate

This form is a statement of final loan terms and closing costs. Compare this Closing Disclosure document with your Loan Estimate. Closing Information Transaction Information Loan Information Date Issued 4/15/2013 Borrower Michael Jones and Mary Stone Loan Term 30 years Closing Date 4/15/2013 123 Anywhere Street Purpose Purchase Disbursement Date 4/15/2013 Anytown, ST 12345 Product Fixed Rate Settlement Agent Epsilon Title Co. Seller Steve Cole and Amy Doe File # 12-3456 321 Somewhere Drive Loan Type x Conventional FHA Property 456 Somewhere Ave Anytown, ST 12345 VA _____________ Anytown, ST 12345 Lender Ficus Bank Loan ID # 123456789 Sale Price $180,000 MIC # 000654321 Loan Terms Can this amount increase after closing? Loan Amount $162,000 NO Interest Rate 3.875% NO Monthly Principal & Interest $761.78 NO See Projected Payments below for your Estimated Total Monthly Payment Does the loan have these features? Prepayment Penalty YES • As high as $3,240 if you pay off the loan during the first 2 years Balloon Payment NO Projected Payments Payment Calculation Years 1-7 Years 8-30 Principal & Interest $761.78 $761.78 Mortgage Insurance + 82.35 + — Estimated Escrow + 206.13 + 206.13 Amount can increase over time Estimated Total Monthly Payment $1,050.26 $967.91 This estimate includes In escrow? Estimated Taxes, Insurance x Property Taxes YES & Assessments $356.13 x Homeowner’s Insurance YES Amount can increase over time a month x Other: Homeowner’s Association Dues NO See page 4 for details See Escrow Account on page 4 for details. You must pay for other property costs separately. -

Conditional Approval #220 December 1996

Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks Washington, DC 20219 Conditional Approval #220 December 2, 1996 December 1996 Mark J. Welshimer, Esquire Sullivan & Cromwell 125 Broad Street New York, N.Y. 10004-2498 Re: Notices of Wells Fargo Bank, N.A., Michigan National Bank, First National Bank of Chicago, and Texas Commerce Bank of Intent to Establish an Operating Subsidiary Pursuant to 12 C.F.R. § 5.34 to Become a Member of Limited Liability Companies Operating a Stored Value System - Application Control Nos. 96-WO-08-0012, -0013, -0025, and -0026 Dear Mr. Welshimer: This is in response to the operating subsidiary notices pursuant to 12 C.F.R. § 5.341, submitted on behalf of Wells Fargo Bank, N.A.(“Wells Fargo”), Michigan National Bank (“MNB”), First National Bank of Chicago, and Texas Commerce Bank, N.A. (collectively, the “Banks”), to establish operating subsidiaries to acquire membership interests in two Delaware limited liability companies (the “LLCs” or the “Companies”) that will operate a stored value card system known as “Mondex.” Each of the operating subsidiaries will be wholly owned by its parent Bank and will engage in no activities other than holding membership interests in the Companies. For the reasons discussed below, we approve, subject to certain conditions, the establishment of such operating subsidiaries by the Banks because we find that national banks may under 12 U.S.C. § 24(Seventh) engage in the business of developing and operating a stored value system. Please note that our response is solely directed to the question stated above. We do not address how other federal and state laws and regulations will or might apply to the Banks’ 1 The OCC recently amended its operating subsidiary rule , 12 C.F.R. -

Application for a Maestro Card

CREDIT SUISSE (Switzerland) Ltd. Application for a Maestro Card Surname, First name / Company Date of birth This application refers to the following account no. IBAN (International Bank Account Number) (hereinafter referred to as the Client) 1. Application for a Maestro Card The Client hereby applies for a Maestro card from Credit Suisse (Switzerland) Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as the Bank). For him/herself, or For the following person (hereinafter referred to as the Authorized Cardholder): Mr. Ms. Surname First name Street/no. Postcode/town Domicile Date of birth Nationality Language of correspondence Card imprint 1st line 2nd line (automatic: cardholder; poss. manual entry of max. 24 characters) (poss. the account holder) The Authorized Cardholder is granted limited account The following services are available with the Maestro card: access rights for this card (Corporate Clients: not Cash withdrawals at ATMs in Switzerland and abroad possible for joint signatory authority). Cashless payment for goods and services in Switzerland Account access rights enable the Authorized Cardholder and abroad to: The Maestro card has a Maestro PIN (Personal query and print out account information at Credit Identification Number) for the use of ATMs and Maestro Suisse ATMs (current account balance, last five terminals at points of sale. transactions) make cash deposits at Credit Suisse ATMs equipped for that purpose. To be completed by the Bank Client no. (CIF) Client no. (CIF) Account holder ________________________________________ Authorized