What Is Atonal?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academiccatalog 2017.Pdf

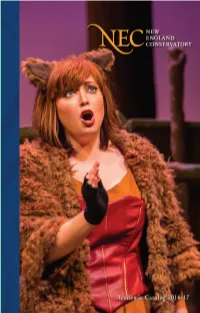

New England Conservatory Founded 1867 290 Huntington Avenue Boston, Massachusetts 02115 necmusic.edu (617) 585-1100 Office of Admissions (617) 585-1101 Office of the President (617) 585-1200 Office of the Provost (617) 585-1305 Office of Student Services (617) 585-1310 Office of Financial Aid (617) 585-1110 Business Office (617) 585-1220 Fax (617) 262-0500 New England Conservatory is accredited by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. New England Conservatory does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, age, national or ethnic origin, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, genetic make-up, or veteran status in the administration of its educational policies, admission policies, employment policies, scholarship and loan programs or other Conservatory-sponsored activities. For more information, see the Policy Sections found in the NEC Student Handbook and Employee Handbook. Edited by Suzanne Hegland, June 2016. #e information herein is subject to change and amendment without notice. Table of Contents 2-3 College Administrative Personnel 4-9 College Faculty 10-11 Academic Calendar 13-57 Academic Regulations and Information 59-61 Health Services and Residence Hall Information 63-69 Financial Information 71-85 Undergraduate Programs of Study Bachelor of Music Undergraduate Diploma Undergraduate Minors (Bachelor of Music) 87 Music-in-Education Concentration 89-105 Graduate Programs of Study Master of Music Vocal Pedagogy Concentration Graduate Diploma Professional String Quartet Training Program Professional -

Alban Berg's Filmic Music

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Goldsmith, Melissa Ursula Dawn, "Alban Berg's filmic music: intentions and extensions of the Film Music Interlude in the Opera Lula" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ALBAN BERG’S FILMIC MUSIC: INTENTIONS AND EXTENSIONS OF THE FILM MUSIC INTERLUDE IN THE OPERA LULU A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The College of Music and Dramatic Arts by Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith A.B., Smith College, 1993 A.M., Smith College, 1995 M.L.I.S., Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 1999 May 2002 ©Copyright 2002 Melissa Ursula Dawn Goldsmith All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to express gratitude to my wonderful committee for working so well together and for their suggestions and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Jan Herlinger, my dissertation advisor, for his insightful guidance, care and precision in editing my written prose and translations, and open mindedness. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

What Is Atonality (1930)

What is Atonality? Alban Berg April 23, 1930 A radio talk given by Alban Berg on the Vienna Rundfunk, 23 April 1930, and, printed under the title “Was ist atonal?” in 23, the music magazine edited by Willi Reich, No. 26/27, Vienna, 8 June 1936. Interlocutor: Well, my dear Herr Berg, let’s begin! considered music. Alban Berg: You begin, then. I’d rather have the last Int.: Aha, a reproach! And a fair one, I confess. But word. now tell me yourself, Herr Berg, does not such a Int.: Are you so sure of your ground? distinction indeed exist, and does not the negation of relationship to a given tonic lead in fact to the Berg: As sure as anyone can be who for a quarter- collapse of the whole edifice of music? century has taken part in the development of a new art — sure, that is, not only through understanding Berg: Before I answer that, I would like to say this: and experience, but — what is more — through Even if this so-called atonal music cannot, har- faith. monically speaking, be brought into relation with a major/minor harmonic system — still, surely, Int.: Fine! It will be simplest, then, to start at once with there was music even before that system in its turn the title of our dialogue: What is atonality? came into existence. Berg: It is not so easy to answer that question with a for- Int.: . and what a beautiful and imaginative music! mula that would also serve as a definition. When this expression was used for the first time — prob- Berg: . -

Modern Art Music Terms

Modern Art Music Terms Aria: A lyrical type of singing with a steady beat, accompanied by orchestra; a songful monologue or duet in an opera or other dramatic vocal work. Atonality: In modern music, the absence (intentional avoidance) of a tonal center. Avant Garde: (French for "at the forefront") Modern music that is on the cutting edge of innovation.. Counterpoint: Combining two or more independent melodies to make an intricate polyphonic texture. Form: The musical design or shape of a movement or complete work. Expressionism: A style in modern painting and music that projects the inner fear or turmoil of the artist, using abrasive colors/sounds and distortions (begun in music by Schoenberg, Webern and Berg). Impressionism: A term borrowed from 19th-century French art (Claude Monet) to loosely describe early 20th- century French music that focuses on blurred atmosphere and suggestion. Debussy "Nuages" from Trois Nocturnes (1899) Indeterminacy: (also called "Chance Music") A generic term applied to any situation where the performer is given freedom from a composer's notational prescription (when some aspect of the piece is left to chance or the choices of the performer). Metric Modulation: A technique used by Elliott Carter and others to precisely change tempo by using a note value in the original tempo as a metrical time-pivot into the new tempo. Carter String Quartet No. 5 (1995) Minimalism: An avant garde compositional approach that reiterates and slowly transforms small musical motives to create expansive and mesmerizing works. Glass Glassworks (1982); other minimalist composers are Steve Reich and John Adams. Neo-Classicism: Modern music that uses Classic gestures or forms (such as Theme and Variation Form, Rondo Form, Sonata Form, etc.) but still has modern harmonies and instrumentation. -

Chapter 28: Neoclassicism and Twelve-Tone Music: 1915–50 I

Chapter 28: Neoclassicism and Twelve-Tone Music: 1915–50 I. Introduction A. The carnage of World War I shattered the ideals of Romanticism. II. The First World War and its impact on the arts A. The wave of shock produced by the Great War reverberated in the arts. A preference emerged for spoken over sung, reason over feeling, and reportage over poetry. III. Neoclassicism A. After shocking the world with the scandalous Rite of Spring (and a few other works), Stravinsky went in an entirely different direction in 1923 with his Octet for woodwinds. This work marks the beginning of a new style: Neoclassicism. 1. This style was marked by “objectivity,” which composers conveyed by bringing back eighteenth-century gestures, although it could include aspects of Baroque, popular music of the 1920s, and even Tchaikovsky. IV. Igor Stravinsky’s Neoclassical path A. At the end of World War I (1918), Stravinsky composed Histoire du soldat. 1. The ensemble was small, by comparison with the Rite, and featured instruments associated with jazz. 2. Soon thereafter, Diaghilev and his recent choreographer Massine teamed up with Stravinsky to do a work based on eighteenth-century music: Pulcinella. 3. These two works (Histoire du soldat and Pulcinella) were stage works, but Stravinsky soon looked to instrumental pieces for this developing new style. 4. The raw aspect of Rite was noted early on. This aspect connects it with the lack of Romanticism (“renunciation of ‘sauce’”) noted in the later works. 5. In the 1920s, irony triumphed over sincerity as an artistic aim. B. The music of Stravinsky’s Octet 1. -

The Elements of Contemporary Turkish Composers' Solo Piano

International Education Studies; Vol. 14, No. 3; 2021 ISSN 1913-9020 E-ISSN 1913-9039 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Elements of Contemporary Turkish Composers’ Solo Piano Works Used in Piano Education Sirin A. Demirci1 & Eda Nergiz2 1 Education Faculty, Music Education Department, Bursa Uludag University, Turkey 2 State Conservatory Music Department, Giresun University, Turkey Correspondence: Sirin A. Demirci, Education Faculty, Music Education Department, Bursa Uludag University, Turkey. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 19, 2020 Accepted: November 6, 2020 Online Published: February 24, 2021 doi:10.5539/ies.v14n3p105 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v14n3p105 Abstract It is thought that to be successful in piano education it is important to understand how composers composed their solo piano works. In order to understand contemporary music, it is considered that the definition of today’s changing music understanding is possible with a closer examination of the ideas of contemporary composers about their artistic productions. For this reason, the qualitative research method was adopted in this study and the data obtained from the semi-structured interviews with 7 Turkish contemporary composers were analyzed by creating codes and themes with “Nvivo11 Qualitative Data Analysis Program”. The results obtained are musical elements of currents, styles, techniques, composers and genres that are influenced by contemporary Turkish composers’ solo piano works used in piano education. In total, 9 currents like Fluxus and New Complexity, 3 styles like Claudio Monteverdi, 5 techniques like Spectral Music and Polymodality, 5 composers like Karlheinz Stockhausen and Guillaume de Machaut and 9 genres like Turkish Folk Music and Traditional Greek are reached. -

I ROW CONSTRUCTION and ACCOMPANIMENT in LUIGI

ROW CONSTRUCTION AND ACCOMPANIMENT IN LUIGI DALLAPICCOLA’S IL PRIGIONIERO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music by DORI WAGGONER Dr. Neil Minturn, Thesis Supervisor December 2007 i The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled ROW CONSTRUCTION AND ACCOMPANIMENT IN LUIGI DALLAPICCOLA’S IL PRIGIIONIERO presented by Dori Waggoner, a candidate for the degree of master of music, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Neil Minturn Professor Stefan Freund Professor Rusty Jones Professor Thomas McKenney Professor Nancy West ii Thank you to my husband and son. Without your support, patience, and understanding, none of this would have been possible. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without the encouragement and advice of Dr. Neil Minturn, this document would not exist. I would like to thank him for encouraging me to listen to the music and to let it guide me through the analysis. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………...….ii LIST OF EXAMPLES……………………………………………………………...iv ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………….……..vi Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….1 Compositional Influences Plot Summary 2. ROW CONSTRUCTION……………………………………………………..9 The Prayer Row The Hope Row The Freedom Row The Chorus Row The Fratello Motif/Row 3. ACCOMPANIMENT………...……………………………………….…….26 Accompaniment that Doubles the Vocal Line Accompaniment by Same Row Accompaniment by Different Row Accompaniment with Chromaticism Accompaniment with Octatonicism 4. CONCLUSIONS……………………………………………………………35 WORKS CITED…………………………………………………………..……….39 iii LIST OF EXAMPLES Example Page 1. Volo di Notte , mm. 382–387………………………………………………….….….6 2. Prayer Row……………………………………………………….…………….…..11 3. -

Theory of Music-Stravinsky

Theory of Music – Jonathan Dimond Stravinsky (version October 2009) Introduction Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was one of the most internationally- acclaimed composer conductors of the 20th Century. Like Bartok, his compositional style drew from the country of his heritage – Russia, in his case. Both composers went on to spend time in the USA later in their careers also, mostly due to the advent of WWII. Both composers were also exposed to folk melodies early in their lives, and in the case of Stravinsky, his father sang in Operas. Stravinsky’s work influenced Bartok’s – as it tended to influence so many composers working in the genre of ballet. In fact, Stravinsky’s influence was so broad that Time Magazine named him one of th the most influential people of the 20 Century! http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Igor_Stravinsky More interesting, however, is the correlation of Stravinsky’s life with that of Schoenberg, who were contemporaries of each other, yet had sometimes similar and sometimes contradictory approaches to music. The study of their musical output is illuminated by their personal lives and philosophies, about which much has been written. For such writings on Stravinsky, we have volumes of work created by his long-term companion and assistant, the conductor/musicologist Robert Craft. {See the Bibliography.} Periods Stravinsky’s compositions fall into three distinct periods. Some representative works are listed here also: The Dramatic Russian Period (1906-1917) The Firebird (1910, revised 1919 and 1945) Petrouchka (1911, revised 1947)) -

Undergraduate Listening List

Undergraduate Composition Listening List Claude Debussy: Nocturnes (1899) CD 1073 M1003.D4 N64 Arnold Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire (1912) CD 8960 M1625.S3 P5 Op. 21 Igor Stravinsky: Rite of Spring (1913) CD 5552 M1520.S9 S3 Bo2 Anton von Webern: Symphony, Op.21 (1929) CD 2566 M1001.W39 S9 1929 Ruth Crawford Seeger: String Quartet (1931) CD 8896 M452.S44 Q8 Alban Berg: Violin Concerto (1935) CD 5665 M1012.B47 Béla Bartók: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste (1936) CD 5590 M1105.B35M8 Bo Olivier Messiaen: Quartet for the End of Time (1941) CD 2292 M422.M48 Q3 Grażyna Bacewicz: Sonata per violino solo No. 2 (1958) Online recording: http://fsu.naxosmusiclibrary.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/catalogue/item.asp?cid=CSCD-95011 M42.B23S66 Elliott Carter: String Quartet #2 (1959) CD 3129 M452.C377 Q82 no. 2 Benjamin Britten: War Requiem, Nos. 2-3 (1962) Online recording: http://fsu.naxosmusiclibrary.com.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/catalogue/item.asp?cid=CHAN8983-84 M2013.B86 W4 Krzysztof Penderecki: St. Luke Passion (1966) Rec3160 SLP M2004.P46.P27 Witold Lutosławski: Livre (1968) CD 2286 M1045.L975.L58 Luciano Berio: Sinfonia, III – In ruhig fliessender Bewegung (1969) CD 8917 M1528.B475 S56 George Crumb: Ancient Voices of Children (1970) CD 9218 M1613.3.C92 A5 Dmitri Shostakovich: String Quartet No.15 (1974) CD 7200 M452.S556 Q8 no. 15, op. 144 Louis Andriessen: De Staat (1972 – 1976) Rec 10095 SLP M1528.A52 S7 1992 John Corigliano: Clarinet Concerto (1977) CD 756 M1025.C67 C6 1993 Steve Reich: Octet (Eight Lines) (1979) CD1654 M885.R34 O37 Sofia Gubaidulina: -

An Analysis of Luigi Dallapiccola's Sicut Umbra

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference 2002, 13th Annual JWP Conference Apr 21st, 10:00 AM - 11:00 AM An Analysis of Luigi Dallapiccola's Sicut Umbra Deborah Miller, '02 Illinois Wesleyan University Mario Pelusi, Faculty Advisor Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc Miller, '02, Deborah and Pelusi, Faculty Advisor, Mario, "An Analysis of Luigi Dallapiccola's Sicut Umbra" (2002). John Wesley Powell Student Research Conference. 3. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/jwprc/2002/oralpres2/3 This is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. THEJOHN WESLEY POWELL STUDENTRESEARCH CONFERENCE ® APRIL 2002 Oral Presentation 02. 1 AN ANALYSIS OF LUIGI DALLAPICCOLA'S SICUT UMBRA Deborah Miller and Mario Pelusi* School of Music, Illinois Wesleyan University Luigi Dallapiccola (1904 - 1975) was one of the most accomplished Italian composers of the twentieth century. Dallapiccola was the first Italian composer to adopt the twelve tone method of composition for his own music (a method created by the Austrian composer, Arnold Schoenberg). -

Chapter Five Leafing Through Wings of Desire

Chapter Five Leafing through Wings of Desire film has a much greater affinity with literature than with photography1 1. Prompting words, many words The fourth and, to date at least, final collaboration of Wenders and Handke, Wings of Desire, is undoubtedly the most famous, having even received the accolade of being given away in the UK as a free DVD with the Independent newspaper in 2006. It is also the least „collaborative‟ of their collaborations: Handke refused to write a screenplay, pleading exhaustion following completion of his novel Repetition (Die Wiederholung, 1986), and was not involved in any way in the production of the film. In what follows, the discussion will concentrate on the relationship between Handke‟s contribution to the film – a series of poetic monologues – and Wenders‟s integration of these texts into his narrative. In order to understand the difficulty, impossibility even, of the task facing Wenders it will be necessary, in the first instance, to consider some of the ways in which Handke‟s writing had developed since Wrong Move, A Moment of True Feeling, and The Left- Handed Woman. Wings of Desire has prompted a torrent of commentary, exegesis, and discourse like no other film of Wenders. In 1999 Richard Raskin compiled a bibliography on the film which includes 18 interviews with the director and 96 reviews and analyses of the film, and the torrent has not abated since then.2 It is also the film of Wenders which has been most eagerly taken up by literary scholars, in particular Germanists, who doubtless feel at home with the film‟s literary style and erudite allusions.