Champa Settlements of the First Millennium New Archaeological Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Jades Map 3,000 Years of Prehistoric Exchange in Southeast Asia

Ancient jades map 3,000 years of prehistoric exchange in Southeast Asia Hsiao-Chun Hunga,b, Yoshiyuki Iizukac, Peter Bellwoodd, Kim Dung Nguyene,Be´ re´ nice Bellinaf, Praon Silapanthg, Eusebio Dizonh, Rey Santiagoh, Ipoi Datani, and Jonathan H. Mantonj Departments of aArchaeology and Natural History and jInformation Engineering, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia; cInstitute of Earth Sciences, Academia Sinica, P.O. Box 1-55, Nankang, Taipei 11529, Taiwan; dSchool of Archaeology and Anthropology, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia; eDepartment of Ancient Technology Research, Vietnam Institute of Archaeology, Hanoi, Vietnam; fCentre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unite´Mixte de Recherche 7528, 27 Rue Paul Bert, 94204 Ivry-sur-Seine, France; gDepartment of Archaeology, Silpakorn University, Bangkok 10200, Thailand; hArchaeology Division, National Museum of the Philippines, Manila, Philippines; and iSarawak Museum, Kuching, Malaysia Edited by Robert D. Drennan, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, and approved October 5, 2007 (received for review August 3, 2007) We have used electron probe microanalysis to examine Southeast Japanese archaeologist Kano Tadao (7) recognized four types of Asian nephrite (jade) artifacts, many archeologically excavated, jade earrings with circumferential projections that he believed dating from 3000 B.C. through the first millennium A.D. The originated in northern Vietnam, spreading from there to the research has revealed the existence of one of the most extensive Philippines and Taiwan. Beyer (8), Fox (3), and Francis (9) also sea-based trade networks of a single geological material in the suggested that the jade artifacts found in the Philippines were of prehistoric world. Green nephrite from a source in eastern Taiwan mainland Asian origin, possibly from Vietnam. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

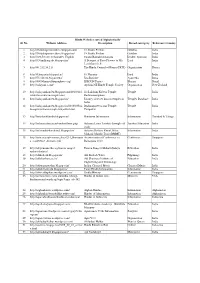

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Ancient Indian History Chapter 14

Chapter 14: THE SPREAD OF INDIAN CULTURE IN OTHER ASIAN COUNTRIES Introduction The spread of Indian culture and civilization to the other parts of Asia constitutes an important chapter in the history of India. India had established commercial contacts with other countries from the earliest times. It had inevitably resulted in the spread of Indian languages, religions, art and architecture, philosophy, beliefs, customs and manners. Indian political adventurers even established Hindu kingdoms in some parts of South East Asia. However, this did not lead to any kind of colonialism or imperialism in the modern sense. On the other hand these colonies in the new lands were free from the control of the mother country. But they were brought under her cultural influence. Chapter 14: THE SPREAD OF INDIAN CULTURE IN OTHER ASIAN COUNTRIES Central Asia Chapter 14: THE SPREAD OF INDIAN CULTURE IN OTHER ASIAN COUNTRIES Central Asia Central Asia was a great centre of Indian culture in the early centuries of the Christian era. Several monuments have been unearthed in the eastern part of Afghanistan. Khotan and Kashkar remained the most important centres of Indian culture. Several Sanskrit texts and Buddhist monasteries were found in these places. Indian cultural influence continued in this region till eighth century. Indian culture had also spread to Tibet and China through Central Asia. Chapter 14: THE SPREAD OF INDIAN CULTURE IN OTHER ASIAN COUNTRIES India and China Chapter 14: THE SPREAD OF INDIAN CULTURE IN OTHER ASIAN COUNTRIES India and China China was influenced both by land route passing through Central Asia and the sea route through Burma. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

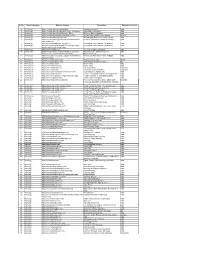

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V. -

Tiếp Xúc Và Giao Thoa Của Văn Hóa Sa Huỳnh Qua Những Phát Hiện Nghiên

TIEÁP XUÙC VAØ GIAO THOA CUÛA VAÊN HOÙA SA HUYØNH QUA NHÖÕNG PHAÙT HIEÄN VAØ NGHIEÂN CÖÙU MÔÙI Lâm Thị Mỹ Dung* Bức khảm Sa Huỳnh - Văn hóa Sa Huỳnh không chỉ là văn hóa mộ chum hay truyền thống mộ chum(1). Cho tới nay đã có nhiều diễn giải về văn hóa Sa Huỳnh cả về không gian phân bố, giai đoạn, tính chất và loại hình của văn hóa Sa Huỳnh, tuy nhiên, trên một bức tranh có thể gọi là ghép mảnh này, những mảng màu cho thấy càng lúc càng rõ tính không đồng nhất cả về sắc cả về hình. Có thể nói bức khảm văn hóa Sa Huỳnh càng ngày càng buộc chúng ta phải Bãi Cọi - Tiếp xúc Đông Sơn Sa Huỳnh Sa Huỳnh Bắc Địa điểm Sa Huỳnh Hòa Diêm và những địa điểm VHSH khác Với chứng cứ liên quan đến truyền thống Kalanay Sa Huỳnh Nam Phú Trường Giồng lớn và Giồng Cá Vồ... Các đảo Phú Quý, Côn Đảo, Phú Quốc Linh Sơn Nam, Óc Eo Ba Thê Bức khảm văn hóa Sa Huỳnh * GS.TS. Trường Đại học Khoa học Xã hội và Nhân văn (Đại học Quốc gia Hà Nội) 22 Thông báo khoa học 2019 ** nhận diện nó một cách chi tiết hơn và đầy đủ hơn để tìm được khối mảng nào là khối mảng chủ đạo, màu sắc nào là màu sắc chính và mức độ đậm nhạt, quy mô của những khối mảng này. Mặc dù vẫn còn những ý kiến chưa hoàn toàn đồng thuận về không gian phân bố của nền văn hóa này, nhưng tiếp cận một không gian văn hóa khảo cổ có phần trung tâm, ngoại vi/ngoại biên, tiếp xúc và lan tỏa và dựa trên những phát hiện gần đây cũng như nhận định của nhiều nhà nghiên cứu, chúng tôi cho rằng những địa điểm văn hóa Sa Huỳnh về cơ bản phân bố trên địa bàn các tỉnh miền Trung Việt Nam từ Hà Tĩnh đến Bình Thuận (bao gồm cả các đảo ven bờ và gần bờ). -

Sa Huy Ure: Recent Di Es

Sa Huy ure: Recent Di es NGO SY HONG to the Metal Age in were discovered 75 ago. discoveries are now Sa Huynh culture. mation culture is limited to jar of habitation are virtually unknown. Concerning its origin, many scholars suggest that its bearers came from Island Southeast Asia. It was originally classified as Neolithic, but later revised as Iron Age. Since 1975, 38 Sa Huynh culture sites have been identified, in addition to the 12 previ ously known. Some major sites have since been excavated on a large scale. From new data, we are able to discern an earlier stage of the Sa Huynh culture which belongs to the Bronze Age. Typical of this early stage is the site of Long Thanh in Nghia Binh Prov- ince, central Viet Nam, which has two radiocarbon both on charcoal, of 3370 ± 40 b.p. 2875 ± 60 b.p. (at 0.6 2(94). At habitation layer is 2 yielded stone pestles, stones, earthenware and thousands of artifacts are similar to sites such as Bau Tro. that from contemporaneous such as Phung Nguyen Hoa Lac. distinguishable from cultures in terms of its flower- vase, ring-footed and long-necked vessel shapes. The burial jars of this stage are egg shaped, whereas those of the later period are cylindrical. Decorative techniques at Long Thanh include incision, shell-edge impression, and painting. Motifs are mostly curvili near scrolls. This early stage finishes with the Binh Chau site in Nghia Binh Province, which has produced an elaborate bronze industry which includes axes, knives, molds, and crucibles. -

Historie Routes to Angkor: Development of the Khmer Road System (Ninth to Thirteenth Centuries AD) in Mainland Southeast Asia Mitch Hendrickson*

Historie routes to Angkor: development of the Khmer road system (ninth to thirteenth centuries AD) in mainland Southeast Asia Mitch Hendrickson* Road systems in the service of empires have long inspired archaeologists and ancient historians alike. Using etymology, textual analysis and Angkor archaeology the author deconstructs the road system of the Khmer, empire builders of early historic Cambodia. Far from being the creation of one king, the road system evolved organically to serve expeditions, pilgrimages Phnom . Penh ù <> and embedded exchange routes over several i centuries. The paper encourages us to regard road networks as a significant topic, worthy of comparative study on a global scale. N 0 ^ 200 Keywords: Cambodia, Khmer, roads, routes, communications Ancient road systems: context and methods of study Investigating the chronology of road systems is complicated by their frequent reuse over long time periods and because they are comprised of multiple archaeological components that range from site to regional scales (e.g. roads, resting places, crossing points, settlements, ceramics). The archaeologist studying road systems must identify and incorporate a variety of available data sets, including historic information, within a framework of operational principles that characterise state-level road building and use. Recent trends in the study of imperial states focus on socio-cultural issues, such as pov^'er and politico-economic organisation (see D'Altroy 1992; Sinopoli 1994; Morrison 2001) and concepts of boundaries ' Department of Archaeology. University af Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia (Email: [email protected]) Received: 28 Au^t 2009; Revised: ¡3 October 2009: Accepted: 12 January 2010 ANTlQUITy84 (2010): 480-496 http://antiquiiy.ac.uk/ant/84/ant840480.htni 480 Mitch Hendrickson (see Morrison 2001; Smith 2005). -

Title the Cham Muslims in Ninh Thuan Province, Vietnam Author(S)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Title The Cham Muslims in Ninh Thuan Province, Vietnam Author(s) NAKAMURA, Rie CIAS discussion paper No.3 : Islam at the Margins: The Citation Muslims of Indochina (2008), 3: 7-23 Issue Date 2008-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/228404 Right © Center for Integrated Area Studies (CIAS), Kyoto University Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University The Cham Muslims in Ninh Thuan Province, Vietnam1 Rie NAKAMURA Universiti Utara Malaysia Abstract This paper discusses the Cham communities in Ninh Thuan Province, Vietnam. The Cham people are one of 54 state recognized ethnic groups living in Vietnam. Their current population is approximately 130,000. They speak a language which belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian language family. In the past, they had a country called, Champa, along the central coast of Vietnam, which was once prosperous through its involvement in maritime trade. While the largest concentration of the Cham people in Vietnam is found in a part of the former territory of Champa, particularly Ninh Thuan and Binh Thuan provinces, there is another group of Cham people living in the Mekong Delta, mostly in An Giang province near the border with Cambodia. There are differences in ethnic self-identification between these two groups of Chams living in the different localities. In general, the Chams living in the former territory of Champa equate being Cham as being descendants of Champa while the Chams of the Mekong Delta view being Cham as being Muslim. -

Champa Citadels: an Archaeological and Historical Study

asian review of world histories 5 (2017) 70–105 Champa Citadels: An Archaeological and Historical Study Đỗ Trường Giang National University of Singapore, Singapore and Institute of Imperial Citadel Studies (IICS) [email protected] Suzuki Tomomi Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara, Japan [email protected] Nguyễn Văn Quảng Hue University of Sciences, Vietnam [email protected] Yamagata Mariko Okayama University of Science, Japan [email protected] Abstract From 2009 to 2012, a joint research team of Japanese and Vietnamese archaeologists led by the late Prof. Nishimura Masanari conducted surveys and excavations at fifteen sites around the Hoa Chau Citadel in Thua Thien Hue Province, built by the Champa people in the ninth century and used by the Viet people until the fifteenth century. This article introduces some findings from recent archaeological excavations undertaken at three Champa citadels: the Hoa Chau Citadel, the Tra Kieu Citadel in Quang Nam Province, and the Cha Ban Citadel in Binh Dinh Province. Combined with historical material and field surveys, the paper describes the scope and structure of the ancient citadels of Champa, and it explores the position, role, and function of these citadels in the context of their own nagaras (small kingdoms) and of mandala Champa as a whole. Through comparative analysis, an attempt is made to identify features characteristic of ancient Champa citadels in general. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2�17 | doi 10.1163/22879811-12340006Downloaded from Brill.com10/09/2021 06:28:08AM via free access Champa Citadels 71 Keywords Cha Ban – Champa – citadel – Hoa Chau – Thanh Cha – Thanh Ho – Thanh Loi – Tra Kieu Tra Kieu Citadel in Quang Nam Among the ancient citadels of Champa located in central Vietnam, the Tra Kieu site in Quang Nam has generally been identified as the early capital, and thus has attracted the interest of many scholars. -

Ÿþh I S O R I C a L I M a G I N a T I O N , D I a S P O R I C I D E N T I T Y a N D I

Historical Imagination, Diasporic Identity And Islamicity Among The Cham Muslims of Cambodia by Alberto Pérez Pereiro A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved November 2012 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Hjorleifur Jonsson, Co-Chair James Eder, Co-Chair Mark Woodward ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2012 ABSTRACT Since the departure of the UN Transitional Authority (UNTAC) in 1993, the Cambodian Muslim community has undergone a rapid transformation from being an Islamic minority on the periphery of the Muslim world to being the object of intense proselytization by foreign Islamic organizations, charities and development organizations. This has led to a period of religious as well as political ferment in which Cambodian Muslims are reassessing their relationships to other Muslim communities in the country, fellow Muslims outside of the country, and an officially Buddhist state. This dissertation explores the ways in which the Cham Muslims of Cambodia have deployed notions of nationality, citizenship, history, ethnicity and religion in Cambodia’s new political and economic climate. It is the product of a multi-sited ethnographic study conducted in Phnom Penh and Kampong Chhnang as well as Kampong Cham and Ratanakiri. While all Cham have some ethnic and linguistic connection to each other, there have been a number of reactions to the exposure of the community to outside influences. This dissertation examines how ideas and ideologies of history are formed among the Cham and how these notions then inform their acceptance or rejection of foreign Muslims as well as of each other. This understanding of the Cham principally rests on an appreciation of the way in which geographic space and historical events are transformed into moral symbols that bind groups of people or divide them. -

On the Extent of the Sa-Huynh Culture in Continental Southeast Asia

On the Extent of the Sa-huynh Culture in Continental Southeast Asia Received 15 March 1979 HENRI FONTAINE HE SA-HUYNH CULTURE, which first came to view in a seaside locality in central T Vietnam, appeared very early on as the culture of a population of skillful sailors. And this view has been confirmed by digs carried out in the Philippines and in eastern Indonesia, where traces of a similar culture were found. The aim of this note is not to insist on the nautical mobility of this population, one capable of crossing the China Sea, but rather to investigate the extension of the Sa-huynh Culture on the continent of Asia, particularly in the interior regions. Few sites have been excavated in a detailed fashion; they are all in Vietnam. Outside of those sites where precise research has taken place, some characteristic objects have acci dentally been found in various places: very typical earrings with two animal heads, bul bous, three-pointed earrings, agate or carnelian beads, certain of which are pentagonal in form; their geographic distribution extends as far as Thailand. The material accompany ing them has not always been noted. In spite of this, all these objects should draw our at tention, especially where they are not in isolation but together in a single site; they can serve to guide us in future investigations. The beads are somewhat less useful as indica tors ofSa-huynh Culture than the earrings. A map (Fig. 1) of the geographic distribution of these objects accompanies this text and it merits a few comments.