The Ethnic Reality of the Kirkuk Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraq Reconstruction Report a Weekly Construction & Sustainment Update 10.20.06

Iraq Reconstruction Report A Weekly Construction & Sustainment Update 10.20.06 Major Project Dispatches Fence Provides Additional Port Security The Umm Qasr security fence project at the port in Basrah Province was was completed on Oct. 5. The $4.1 million project installed approximately 8 kilometers of security fencing around the north and south port facilities. The project also included the building of an interior perimeter access road, observation posts, perimeter lighting, and back-up power capability. Major Baghdad Road Paving Project Completed Construction is complete on the road repair and paving project in Baiya, Baghdad Province. The $2.4 million project repaired and paved approximately 10 kilometers of Highway 8 between the Al Baiya/Qadisiya overpass and the Rashid Market traffic circle. Work included sealing cracks, patching potholes, road surface cleaning, and installing traffic signs. Construction Begins on an Al-Anbar Pump Station The Baghdad Central Train Station is a $6 million project Construction started on a Fallujah sewer system pump station in Al- completed by the Al Munshed Group, an Iraqi company. The Anbar Province. The $3.8 million project began this month, and has a station administrative offices, restaurant, kitchen areas, bank, June 2007 estimated completion date. The project will construct a facility post office, telegraph office and ticketing offices were all refurbished. (Gulf Region Division Photo) that will pump wastewater from five collection systems to a trunk collection system. The project will benefit approximately 140,000 Inside this Issue residents of Fallujah. Page 2 Gulf Region Division Change of Command Bringing Hope to Tarmiya Page 3 Sector Overview Page 4 School’s “In” Potable Water Page 5 New Police Training Station Capabilities Being UNDG Oversees Infrastructure Rehabilitation Page 6 Hole Repair: Important Work in Iraq Rebuilt Equipment Donated to Veterinary Center Page 8 DoD Reconstruction Partnership A Fallujah worker at the new Al Askari water treatment US Army Corps of Engineers - Gulf Region plant. -

Iraq Reconstruction Weekly Update اﻻﺳﺒﻮﻋﻰ ﻟﻤﺸﺎرﻳﻊ اﻋﻤﺎر اﻟﻌﺮاق اﻟﺘﺤﺪﻳﺚ

Iraq Reconstruction Weekly Update اﻻﺳﺒﻮﻋﻰ ﻟﻤﺸﺎرﻳﻊ اﻋﻤﺎر اﻟﻌﺮاق اﻟﺘﺤﺪﻳﺚ 12.07.05 ﺗﻄﻮر اﻟﺤﺪث واﻻﺧﺒﺎر اﻟﺠﻴﺪة ﺗﻘﺎرﻳﺮ ﻋﻦ Reporting progress and good news Progress Dispatches - Al Husseiniya Primary Healthcare Center Construction is 91% complete on the $653,000 primary healthcare center project in Rusafa, Baghdad Governorate. The project started in Oct. 2004 and will be completed Project Close Up… this month. The two-story, 1,155 BAGHDAD, Iraq – Iraqi police assigned to the newly square meter facility will provide modernized Najaf police station register their approval of medical and dental examination and treatment. The facility will the site’s renovation. Story Page ( Photo by Denise Calabria) be able to treat about 150 patients daily. This is one of 29 primary healthcare center projects programmed in the Baghdad Governorate. Notable Quotes - Al Kut Wasit Underground Line: Project Complete “You are in our way -- please leave so we can get back to work.” Construction has been completed on an electricity project that will Mr. Alla, an Iraqi sewer construction laborer, to reporters. provide service to over 200 Iraqi homes in Al Kut, Wasit (Oct. 2005) Governorate. The $1.5M Wasit Underground Line project installed Inside this Issue two new underground electrical feeders from the Al Kut South substation to the Al Ezah substation which will provide incoming Page 2 - Change of Charter - Electrical Substation Recognized for Excellence power to approximately 2,000 local residents. The Iraqi contractor Page 3 - Contracting Offices Help Boost Iraq’s Economy employed an average of 28 Iraqi workers daily on the site. - Control of Major Power Projects Turned Over - Al Shuada Sewer Work - Diwaniyah Rail Station: Project Complete Page 4 - Latest Project Numbers Page 5 - Sector Overview: Current Status/Impact Construction has been completed on Page 6 - Spotlight on Design-Build Contractors $181,000 railroad station project in Diwaniyah - Unit-Level Assistance in the News District, Al Qadisiyah Governorate. -

The Extent and Geographic Distribution of Chronic Poverty in Iraq's Center

The extent and geographic distribution of chronic poverty in Iraq’s Center/South Region By : Tarek El-Guindi Hazem Al Mahdy John McHarris United Nations World Food Programme May 2003 Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................1 Background:.........................................................................................................................................3 What was being evaluated? .............................................................................................................3 Who were the key informants?........................................................................................................3 How were the interviews conducted?..............................................................................................3 Main Findings......................................................................................................................................4 The extent of chronic poverty..........................................................................................................4 The regional and geographic distribution of chronic poverty .........................................................5 How might baseline chronic poverty data support current Assessment and planning activities?...8 Baseline chronic poverty data and targeting assistance during the post-war period .......................9 Strengths and weaknesses of the analysis, and possible next steps:..............................................11 -

Major Strategic Projects Available for Investment According to Sectors

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission MAJOR STRATEGIC (LARGE) AND (MEDIUM-SIZE)PROJECTS AVAILABLE FOR INVESTMENT ACCORDING TO SECTORS NUMBER OF INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES ACCORDING TO SECTORS No. Sector Number of oppurtinites Major strategic projects 1. Chemicals, Petrochemicals, Fertilizers and 18 Refinery sector 2 Transportation Sector including (airports/ 16 railways/highways/metro/ports) 3 Special Economic Zones 4 4 Housing Sector 3 Medium-size projects 5 Engineering and Construction Industries Sector 6 6 Commercial Sector 12 7 tourism and recreational Sector 2 8 Health and Education Sector 10 9 Agricultural Sector 86 Total number of opportunities 157 Major strategic projects 1. CHEMICALS, PETROCHEMICALS, FERTILIZERS AND REFINERY SECTOR: A. Rehabilitation of existing fertilizer plant in Baiji and the implementation of new production lines (for export). • Production of 500 ton of Urea fertilizer • Expected capital: 0.5 billion USD • Return on Investment rate: %17 • The plant is operated by LPG supplied by the North Co. in Kirkuk Province. 9 MW Generators are available to provide electricity for operation. • The ministry stopped operating the plant on 1/1/2014 due to difficult circumstances in Saladin Province. • The plant has1165 workers • About %60 of the plant is damaged. Reconstruction and development of fertilizer plant in Abu Al Khaseeb (for export). • Plant history • The plant consist of two production lines, the old production line produced Urea granules 200 t/d in addition to Sulfuric Acid and Ammonium Phosphate. This plant was completely destroyed during the war in the eighties. The second plant was established in 1973 and completed in 1976, designed to produce Urea fertilizer 420 thousand metric ton/y. -

Investment Map of Iraq 2016

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission Investment Map of Iraq 2016 Dear investor: Investment opportunities found in Iraq today vary in terms of type, size, scope, sector, and purpose. the door is wide open for all investors who wish to hold investment projects in Iraq,; projects that would meet the growing needs of the Iraqi population in different sectors. Iraq is a country that brims with potential, it is characterized by its strategic location, at the center of world trade routes giving it a significant feature along with being a rich country where I herby invite you to look at Iraq you can find great potentials and as one of the most important untapped natural resources which would places where untapped investment certainly contribute in creating the decent opportunities are available in living standards for people. Such features various fields and where each and characteristics creates favorable opportunities that will attract investors, sector has a crucial need for suppliers, transporters, developers, investment. Think about the great producers, manufactures, and financiers, potentials and the markets of the who will find a lot of means which are neighboring countries. Moreover, conducive to holding new projects, think about our real desire to developing markets and boosting receive and welcome you in Iraq , business relationships of mutual benefit. In this map, we provide a detailed we are more than ready to overview about Iraq, and an outline about cooperate with you In order to each governorate including certain overcome any obstacle we may information on each sector. In addition, face. -

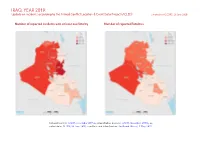

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

IRAQ, YEAR 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 1282 452 1253 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 2 Protests 845 12 72 Battles 719 541 1735 Methodology 3 Riots 242 72 390 Conflict incidents per province 4 Violence against civilians 191 136 240 Strategic developments 190 6 7 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 3469 1219 3697 Disclaimer 7 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from 2016 to 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 IRAQ, YEAR 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology on what level of detail is reported. Thus, towns may represent the wider region in which an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province The data used in this report was collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event is known. -

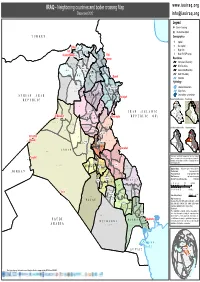

IRAQ - Neighboring Countries and Boder Crossing Map December 2012 [email protected]

IRAQ - Neighboring countries and boder crossing Map www.iauiraq.org December 2012 [email protected] Legend ! Border Crossing Ä International Airport TURKEY Demographics \! Capital H! Gov Capital Habur ZAKHO ! !R Zakho ! AMEDI!R R Major City Tall Amedi DAHUK MERGASUR DAHUK # Major Ref/IDP camps SUMEL Mergasur Hajj Kushik(Rabiah) ! Lower H Dahuk !R ! Akre SORAN !R Umran Boundaries AL-SHIKHAN!R Ain Soran AKRE R! ! Sifne CHOMAN TILKAIF R! Choman International Boundary TELAFAR [1] Tilkef !R SHAQLAWA Shaqlawa KRG Boundary Ta la fa r !R !R Mosul H! SINJAR!R Sinjar !ÄAL-HAMDANIYA!R RANIA PSHDAR Governorate Boundary Al Hamdaniyah R! Ranya ERBIL!ÄH! MOSUL Erbil ERBIL Koysinjaq District Boundary NINEWA R! KOISNJAQ Baneh DOKAN ! Coastline MAKHMUR Hydrology !R Makhmur SHARBAZHER AL-BA'AJ Dibs PENJWIN !R DABES Penjwin R! Hatra Sulaymaniyah Lakes and reservoirs !R Chamchamal H! R! Ä HATRA Kirkuk AL-SHIRQAT H! SULAYMANIYA Major rivers KIRKUK R! !R SULAYMANIYAHSaid Land subject to inundation KIRKUKHaweeja Dukaro Sadiq SYRIAN ARAB R! HALABJA AL-HAWIGA DAQUQ CHAMCHAMAL Halabja Halabjah DARBANDIHKAN R! Darbandikhan ! Disputed Internal Boundaries: Elevation map: REPUBLIC R! Dahuk Bayji !R Touz Erbil Hourmato Ninawa R! KALAR BAIJI Kirkuk TOOZ Sulaymaniyah Salah Kfri Al Din Diala R! RA'UA Kalar Tikrit R! Baghdad H! IRAN (ISLAMIC Anbar TIKRIT Karbala Babil Wassit KIFRI Al Door AL-DAUR Qadissia Missan Al Bukamal !R Khanaquin REPUBLIC OF) Thi – Al Qa'im Najaf Qar ! R! Anah SALAH AL-DIN Khanaqin ! R! R! Basrah Muthana AL-KA'IM SAMARRASamarra !R HADITHA R! KHANAQIN -

IRAQ - Syrian Refugee Camps Map W W W

IRAQ - Syrian Refugee Camps Map w w w . i a u i r a q . o r g August 2012 i n f o @ i a u i r a q . o r g Legend Habur ZAKHO Zakho !R (! Amedi Demographics AME DI !R D A HU K T U R K E Y MER GASUR \! Capital DAHUK Domiz Camp ! SUM EL Dahuk H Gov Capital !H Mergasur Lower Tall Kushik(Rabiah) Refugee Population : 8990 !R ! SOR AN R Major City (! Akre Alkasek Camp AL -SHIKHAN AKR E !R e Ain Sifne Hajj Umran !R Refugee Population : 0 B u h a y r a t ) Soran e Camps TEL AFAR er !R (! iv CHOMAN S a d d a m R b !RChoman [1] TILKAIF Z a Boundaries re at (G Tilkef ir !R b a SHAQLAWA K l International Boundary e A b !RShaqlawa !RTalafar Mosul a I R Z A Governorate Refugee number Sinjar N KRG Boundary !H !R z PSHDAR SINJAR Al Hamdaniyah A RANIA !R h r Ranya AL -HAMDANIYA Na ER B IL !R Governorate Boundary 8990 Erbil Duhok !H District Boundary ERB IL Koysinjaq !R MOS UL DOKAN Coastline 4272 KOISNJAQ Baneh N IN E WA Primary routes Anbar (! Express way 2144 Makhmur Hydrology MAKHMUR !R Erbil SHAR BAZHE R PENJWIN Lakes and reservoirs Dibs !R N AL -B A'AJ a Penjwin h DAB ES SU L AY M A N IYA H !R Major rivers 492 Hatra r Sulaymaniyah !R D Chamchamal !H !R Land subject to inundation i Sulemaniyah j l a !H SUL AYM ANIYA h HATR A KIRKUK ( Kirkuk Disputed Internal Boundaries: Elevation map: AL -SHIRQAT T 0 i g CHAMCHAMAL !R Dahuk r Haweeja Said Sadiq is !R Mosul R KIR KU K Ninawa Erbil iv Dukaro e AL -HAWIGA !R Kirkuk r HALAB JA Sulaymaniyah ) DAR BANDIHKAN Halabja Salah !R Al Din Diala 15898 DAQUQ Darbandikhan (! !R Baghdad Anbar Halabjah Wassit Total Karbala Babil Zero Syrian refugee presence in camp Rabiah Qadissia Missan Thi – - Mosul. -

LTC John Steele

Our Army at War -- Relevant and Ready Background • LTC John Steele • Armor Officer – Tank Platoon Leader Desert Shield/Storm (3 AD), Company Command 2 ID Korea • TF Falcon (Camp Bondsteel), Kosovo, 1 AD Staff Officer • 1AD - 2-37 AR Executive Officer – May to Oct 03 Baghdad • 3d SQDN 2d ACR Operations Officer - Oct 03 to Jul 04 – Baghdad, Al Kut, Najaf, Diwaniya, Al Kufa, Afak, Al-Hillah • 2d ACR and 2d CR Executive Officer Jul 04 to Jun 06 – Fort Polk to Fort Lewis – Unit Generation for SBCT #4 The SBCT The Army Vision “A force that is deployable, agile, versatile, lethal, survivable, sustainable, and dominant at every point along the spectrum of operations…” •Operational/Deployable Force •Medium Weight Force •The best characteristics of both light and heavy forces •Early Entry Force •Bridge to the Future Force • Core operational capabilities – Strat, operational and tactical mobility – Enhanced sit understanding – Full spectrum capability – Combined arms integration down to company level – Decisive action through use of Infantry (close cbt; urban and complex terrain) – Reach back capability • Fully integrated within joint cont force – Deploys rapidly; executes early entry – Conducts effective combat operations with fully- integrated fires – ABCS – GCCS integration – Prevents, contains, stabilizes, or resolves conflict Stryker Vehicles are 312 pieces of equipment out of over 55K in “ I have watched this vehicle save my soldiers lives an SBCT…… and enable them to kill our nation’s enemies. In urban combat there is no better vehicle for delivering a squad of infantrymen to close with and destroy the enemy. It is fast, quiet, incredibly survivable, reliable, lethal, and capable of providing amazing situational awareness. -

Nippur and Archaeology in Iraq

oi.uchicago.edu/oi/AR/04-05/04-05_AR_TOC.html NIPPUR AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN IRAQ NIPPUR AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN IRAQ McGuire Gibson Iraq continues in a state of chaos, and the archaeological sites in the south of the country are still being looted. More than two years of constant digging have destroyed many of the most impor- tant Sumerian and Babylonian cities. Umma, Zabalam, Bad Tibira, Adab, Shuruppak, and Isin are only the most prominent cities that we know have been riddled with pits and tunnels. Hun- dreds of other, as yet unidentified or less-known sites, such as Umm al-Hafriyat, Umm al- Aqarib, Tell Shmid, Tell Jidr, and Tell al-Wilayah are equally damaged. I have just been told by a very brave German archaeologist, who is married to an Iraqi and has recently returned from Iraq, that the diggers are moving north to the vicinity of Baghdad. One of the sites she men- tioned is Tell Agrab, in the Diyala Region, which the Oriental Institute investigated in the 1930s. There are other sites among the ones mentioned above that have a connection with Chicago. Adab (Tell Bismaya) was excavated by Edgar James Banks for the University in 1904/05, be- fore the Institute existed. Umm al-Hafriyat was a remarkable site out in the desert 30 km east of Nippur, where I worked for a season in 1977. This site is located on an ancient river levee that has remarkably plastic clay, and it was because of this resource that the site existed. We mapped more than 400 pottery kilns in and around the town, and we also located at least one brick kiln. -

Idp's Governorate of Origin (2014 Displacement) Iom Iraq

IOM IRAQ DTM INTERIM REPORT IDP’S GOVERNORATE OF ORIGIN (2014 DISPLACEMENT) • Creation Date: 22 August 2014 • Feedback: [email protected] Turkey Turkey Zakho Amedi Zakho Amedi Dahuk From Anbar Dahuk From Ninewa Mergasur Mergasur Dahuk Soran Dahuk Soran Simele Simele Shekhan Shekhan Akre Tal afar Al Shikhan Choman Ta l a fa r Al Shikhan Akre Choman Tilkef Tilkef Shaqlawa Shaqlawa Sinjar Al Hamdaniyah Pshdar Sinjar Al Hamdaniyah Erbil Rania Erbil Rania Pshdar Mosul Arbil Koisnjaq Mosul Arbil Ninewa Ninewa Koisnjaq Dukan Dukan Makhmur Makhmur Sharbazher Sharbazher Dibis Penjwin Dibis Penjwin Al Ba'aj Al Ba'aj Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Kirkuk Sulaymaniyah Syria Hatra Al Shirkat Syria Sulaymaniya Hatra Al Shirkat Sulaymaniya Haweeja Kirkuk Halabja Haweeja Kirkuk Halabja Daquq Daquq Chamchamal Darbandokeh Chamchamal Darbandokeh Iran Iran Kalar Bayji Kalar Touz Hourmato Bayji Touz Hourmato Tikrit Tikrit Al Door Kifri Al Door Kifri Salah al-Din Salah al-Din Anah Khanaqin Anah Khanaqin Al Qa'im Samarra Al Qa'im Samarra Al Haditha Al Khalis Al Haditha Al Khalis Diyala Diyala Balad Balad Hit Al Miqdadiyah Hit Al Miqdadiyah Al-FarisBa`qubah Al-FarisBa`qubah Baghdad Balad Ruz Balad Ruz Ar Ramadi Kadhimiya Kadhimiya Baghdad Adhamiya Ar Ramadi Abu Ghraib Abu GhraibAdhamiya Al-Mada'in Al-Mada'in Al Fallujah Mahmudiya Badrah Al FallujahMahmudiya Badrah Anbar As Suwayrah Anbar As Suwayrah Al MisiabAl Mahawil Al MisiabAl Mahawil Babylon Wassit Wassit Jordan Karbala Karbala Babylon Ar Rutbah Al Kut Jordan Ar Rutbah Al Kut Ain Al Tamur Kerbala Al Jadwal al Gharbi -

Iraq: CCCM Operational Context

IRAQ: Operational context map - IDP Temporary Settlements and Populations CCCM - IRAQ IMU 23 Mar 2017 Caspian Sea Caspian Sea Akre Baharka Hamdaniya NINAWA Berseve 2 Darkar Bajet Zakho Derkar Zakho Batifa Harshm TURKEY Dawadia Kandala Chamishku Berseve 1 Amadiya DOHUK Amedi Sheladize Ankawa 2 Rwanga Mergasur Dahuk Darkar Community Barzan Soran Sumel Dahuk Sumel Mergasur Berseve 1 Chamishku Shariya Akre Berseve 2 Essian Shikhan Erbil Shikhan Qasrok Akre Zakho Kabarto 2 Sheikhan Telafar Zumar Mamilian Soran Choman Mamrashan Rawanduz Garmawa Nargizlia 1 Rovia Choman Amalla TilkaifNargizlia 2 Harir Bardarash Tilkaif Zelikan Bashiqah Shaqlawa (new) Shaqlawa Pirmam MHoasmuldaniya Kawrgosk Baretle (Masif) Baharka Hiran Sinjar Bakhdida Khushan Rania Pshdar Bahirka Rania Qalat Hamdaniya Chwarqurna Erbil Aynkawah Erbil diza Rwanga Chamakor Binaslawa Hajyawa Bajet Hamam Al Alil Mamyzawa Community Mosul Hamam Al Alil 1 Kuna Koisnjaq Kandala Ba'Aj As Salamyiah 2 As Salamyiah 1 Erbil Gork Koisnjaq NINAWA ERBIL Dokan Dokan ERBIL Mousil governorate Mawat Debaga 1 Surdesh Qayyarah camp DOHUK Al Qaiyara Debaga 2 Airstrip Debaga Hamdaniyah Sharbazher Garmik Makhmur Chwarta Qayyarah-Jad'ah Stadium Dabes Penjwin Ba'aj Haj Ali Penjwin Hatra Dabes Bazyan Dahuk Basateen As Sulaymaniyah Shirqat Chamchamal Ashti Barzinja Al Sheuokh Kirkuk Hatra Sulaymaniya IDP Laylan Barzinja Arbat Seyyed Shirqat Qara Halabjay Sadeq Hawiga Kirkuk Laylan C IDP Arbat Taza Dagh Khurmal Yahyawa Laylan 2 Sirwan Taza Khurmatu Qadir IDPDukaro Biara Hawiga KIRKUK Qarim SULAYMANIYAH Sumel