Pakistan Water and Power Development Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dasu Hydropower Project

Public Disclosure Authorized PAKISTAN WATER AND POWER DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (WAPDA) Public Disclosure Authorized Dasu Hydropower Project ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Report by Independent Environment and Social Consultants Public Disclosure Authorized April 2014 Contents List of Acronyms .................................................................................................................iv 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 1.1. Background ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2. The Proposed Project ............................................................................................... 1 1.3. The Environmental and Social Assessment ............................................................... 3 1.4. Composition of Study Team..................................................................................... 3 2. Policy, Legal and Administrative Framework ...............................................................4 2.1. Applicable Legislation and Policies in Pakistan ........................................................ 4 2.2. Environmental Procedures ....................................................................................... 5 2.3. World Bank Safeguard Policies................................................................................ 6 2.4. Compliance Status with -

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Current Rain Spell (31082020 to 04092020 at 11:00 Pm)

PDMA PROVINCIAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY Provincial Emergency Operation Center Civil Secretariat, Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Phone: (091) 9212059, 9213845, Fax: (091) 9214025 www.pdma.gov.pk No. PDMA/PEOC/SR/2020/SepM125 Date: 04/09/2020 KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA CURRENT RAIN SPELL (31082020 TO 04092020 AT 11:00 PM) INFRA/ HUMAN INCIDENTS NATURE OF CAUSE OF CATTLE DISTRICT HUMAN LOSSES/ INJURIES INFRASTRUCTURE DAMAGES INCIDENT INCIDENT PERISHED DEATH INJURED HOUSES SCHOOLS OTHERS Male Female Child Total Male Female Child Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total Fully Partially Total House Collapse/Room Mardan Heavy Rain 0 0 0 0 4 4 1 9 0 0 6 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse Boundry Wall Collapse/Cattle Swabi Heavy Rain Shed/House 0 1 4 5 4 1 3 8 1 1 9 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse/Room Burnt/Room Collapse House Collapse/Room Charsadda Heavy Rain 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse Nowshera Heavy Rain House Collapse 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 11 11 0 0 0 0 0 0 Boundry Wall Collapse/Cattle Shed/House Buner Heavy Rain 0 2 3 5 0 1 2 3 5 6 121 127 0 0 0 0 0 0 Collapse/Roof Collapse/Room Collapse House Collapse/Room UpperChitral Heavy Rain 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 0 0 0 0 5 5 Collapse Malakand Heavy Rain House Collapse 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 14 0 0 0 0 0 0 Lower Dir Heavy Rain House Collapse 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 0 0 0 0 0 0 Boundry Wall Collapse/House Shangla Heavy Rain Collapse/Roof 1 0 3 4 0 4 2 6 12 2 40 42 0 0 0 0 2 2 Collapse/Room Collapse Boundry Wall Collapse/Flash Heavy Rain/Land Flood/Heavy Swat 7 2 2 11 5 0 4 9 0 3 27 30 0 0 -

Languages of Kohistan. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 1 LANGUAGES OF KOHISTAN Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Calvin R. Rensch Sandra J. Decker Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2002 ISBN 969-8023-11-9 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................viii Maps................................................................................................................. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority Audit Year 2015-16

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF EARTHQUAKE RECONSTRUCTION & REHABILITATION AUTHORITY AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ........................................................................... i PREFACE .............................................................................................................. vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................ vii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ..............................................................................1 I Audit Work Statistics ..............................................................................1 II Audit observations regarding Financial Management ...........1 III Outcome Statistics ............................................................................2 IV Table of Irregularities pointed out ..............................................3 V Cost-Benefit ........................................................................................3 CHAPTER-1 Public Financial Management Issues (Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority 1.1 Audit Paras .............................................................................................4 CHAPTER-2 Earthquake Reconstruction & Rehabilitation Authority (ERRA) 2.1 Introduction of Authority .....................................................................18 2.2 Comments on Budget & Accounts (Variance Analysis) .....................18 2.3 Brief comments on the status of compliance -

Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I

Form-V: List of Contesting Candidates NA-1 Peshawar-I Serial No Name of contestng candidate in Address of contesting candidate Symbol Urdu Alphbeticl order Allotted 1 Sahibzada PO Ashrafia Colony, Mohala Afghan Cow Colony, Peshawar Akram Khan 2 H # 3/2, Mohala Raza Shah Shaheed Road, Lantern Bilour House, Peshawar Alhaj Ghulam Ahmad Bilour 3 Shangar PO Bara, Tehsil Bara, Khyber Agency, Kite Presented at Moh. Gul Abad, Bazid Khel, PO Bashir Ahmad Afridi Badh Ber, Distt Peshawar 4 Shaheen Muslim Town, Peshawar Suitcase Pir Abdur Rehman 5 Karim Pura, H # 282-B/20, St 2, Sheikhabad 2, Chiragh Peshawar (Lamp) Jan Alam Khan Paracha 6 H # 1960, Mohala Usman Street Warsak Road, Book Peshawar Haji Shah Nawaz 7 Fazal Haq Baba Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H Ladder !"#$%&'() # 1413, Peshawar Hazrat Muhammad alias Babo Maavia 8 Outside Lahore Gate PO Karim Pura, Peshawar BUS *!+,.-/01!234 Khalid Tanveer Rohela Advocate 9 Inside Yakatoot, PO Chowk Yadgar, H # 1371, Key 5 67'8 Peshawar Syed Muhammad Sibtain Taj Agha 10 H # 070, Mohala Afghan Colony, Peshawar Scale 9 Shabir Ahmad Khan 11 Chamkani, Gulbahar Colony 2, Peshawar Umbrella :;< Tariq Saeed 12 Rehman Housing Society, Warsak Road, Fist 8= Kababiyan, Peshawar Amir Syed Monday, April 22, 2013 6:00:18 PM Contesting candidates Page 1 of 176 13 Outside Lahori Gate, Gulbahar Road, H # 245, Tap >?@A= Mohala Sheikh Abad 1, Peshawar Aamir Shehzad Hashmi 14 2 Zaman Park Zaman, Lahore Bat B Imran Khan 15 Shadman Colony # 3, Panal House, PO Warsad Tiger CDE' Road, Peshawar Muhammad Afzal Khan Panyala 16 House # 70/B, Street 2,Gulbahar#1,PO Arrow FGH!I' Gulbahar, Peshawar Muhammad Zulfiqar Afghani 17 Inside Asiya Gate, Moh. -

Islamic Republic of Pakistan Registrar

National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Islamic Republic of Pakistan NEPRA Tower, Ataturk Avenue(East), G-511, Islamabad Ph: +92-51-9206500, Fax: +92-51-2600026 Registrar Web: www.nepra.org.pk, E-mail: [email protected] No. NEPRA/R/LAG-23/ ?,2 January 09, 2015 General Manager (Hydel) Operations Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) 186 - WAPDA House, Shahrah-e-Quaid-e-Azam, Lahore Subject: Modification-IV in Generation Licence No. GL(Hydel)/05/2004, dated 03.11.2004 — WAPDA for its Hvdel Power Stations It is intimated that the Authority has approved "Licensee Proposed Modification" in Generation Licence No. GL(Hydel)/05/2004 (issued on November 03, 2004) in respect of Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) for its Hydel Power Stations pursuant to Regulation 10(11) of the NEPRA Licensing (Application & Modification Procedure) Regulations, 1999. 2. Enclosed please find herewith determination of Authority in the matter of Licensee Proposed Modification of WAPDA of its Hydel Power Stations along with Modification-IV in the Generation Licence No. GL/(Hydel)/05/20 proved by the Authority. Encl:/As above (Syed Safeer Hussain) Copy to: NEPRIx 1. Secretary, Ministry of Water and Power, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad 2. Secretary, Ministry of Finance, Government of Pakistan, Islamabad 3. Chief Executive Officer, NTDC, 414-WAPDA House, Lahore 4. Chief Operating Officer, CPPA, 107-WAPDA House, Lahore 5. Director General, Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency, Plot No. 41, Street No. 6, H-8/2, Islamabad. National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA ) Determination of Authority in the Matter of Licensee Proposed Modification (LPM) of Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA ) January 05, 2015 Application No. -

765Kv Dasu Transmission Line Project Resettlement Action Plan (Rap)

GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN MINISTRY OF ENERGY (POWER DIVISION) NATIONAL TRANSMISSION & DISPATCH COMPANY (NTDC) 765KV DASU TRANSMISSION LINE PROJECT RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) November 2019 National Transmission & Despatch Company Ministry of Energy (Power Division) Government of Pakistan National Transmission & Despatch Company TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND COMPONENTS ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 Project Description and Components ................................................................................................ 1 1.2.2 Access Tracks and Roads ................................................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Construction Methodology ............................................................................................................... 4 1.2.4 Project Cost and Construction Time .................................................................................................. 6 1.3 THE PROJECT AREA .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.4 PROJECT BENEFITS AND IMPACTS -

Kandiah Hydropower (Private) Limited

KANDIAH HYDROPOWER (PRIVATE) LIMITED SCHEDULE I (Regulation 3(1)) The Registrar National Electric Power Regulatory Authority SUBJECT: APPLICATION FOR A GENERATION LICENSE TO NEPRA I, Mobashir A. Malik, Chief Executive Officer being the duly authorized representative Kandiah Hydropower (Private) Limited, by virtue of Board Resolution dated 27th June 2015 hereby apply to the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority for the grant of a Generation License to the Karot Power Company (Pvt) Limited, pursuant to section (3) of the Regulation of Generation, Transmission and Distribution of Electric Power Act, 1997. I certify that the documents-in-support attached with this application are prepared and submitted in conformity with provisions of the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Licensing (Application and Modification Procedure) Regulation, 1999 and undertake to abide by the terms and provisions of the above said regulations. I further undertake and confirm that the information provided in the attached documents in support is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. A bank draft # 0201 2 .C:1), in the sum of Rupees 619 '71.(1)being the non-refundable license application fee calculated in accordance with Schedule-II to the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority Licensing (Application and Modification Procedure) Regulations, 1999, is also attached herewith. I Mobashir A. Malik Chief Executive Officer Date: 28 JuIV 2015 1 tk. (4, +.2:ani;k21 . V I* - ,, • SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN COMPANY REGISTRATION OFFICE 1st Floor SLIC Building No.7, Blue Area, Islamabad CERTIFICATE OF INCORPORATION [Under Section 32 of the Companies Ordinance, 1984 ()GAIT of 1984) Corporate Universal Identification No. -

1951-81 Population Administrative . Units

1951- 81 POPULATION OF ADMINISTRATIVE . UNITS (AS ON 4th FEBRUARY. 1986 ) - POPULATION CENSUS ORGANISATION ST ATIS TICS DIVISION GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN PREFACE The census data is presented in publica tions of each census according to the boundaries of districts, sub-divisions and tehsils/talukas at the t ime of the respective census. But when the data over a period of time is to be examined and analysed it requires to be adjusted fo r the present boundaries, in case of changes in these. It ha s been observed that over the period of last censuses there have been certain c hanges in the boundaries of so me administrative units. It was, therefore, considered advisable that the ce nsus data may be presented according to the boundary position of these areas of some recent date. The census data of all the four censuses of Pakistan have, therefore, been adjusted according to the administ rative units as on 4th February, 1986. The details of these changes have been given at Annexu re- A. Though it would have been preferable to tabulate the whole census data, i.e., population by age , sex, etc., accordingly, yet in view of the very huge work involved even for the 1981 Census and in the absence of availability of source data from the previous three ce nsuses, only population figures have been adjusted. 2. The population of some of the district s and tehsils could no t be worked out clue to non-availability of comparable data of mauzas/dehs/villages comprising these areas. Consequently, their population has been shown against t he district out of which new districts or rehsils were created. -

PAKISTAN WATER and POWER DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (April

PAKISTAN WATER AND POWER DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (April 2011) April 2011 www.wapda.gov.pk PREFACE Energy and water are the prime movers of human life. Though deficient in oil and gas, Pakistan has abundant water and other energy sources like hydel power, coal, wind and solar power. The country situated between the Arabian Sea and the Himalayas, Hindukush and Karakoram Ranges has great political, economic and strategic importance. The total primary energy use in Pakistan amounted to 60 million tons of oil equivalent (mtoe) in 2006-07. The annual growth of primary energy supplies and their per capita availability during the last 10 years has increased by nearly 50%. The per capita availability now stands at 0.372 toe which is very low compared to 8 toe for USA for example. The World Bank estimates that worldwide electricity production in percentage for coal is 40, gas 19, nuclear 16, hydro 16 and oil 7. Pakistan meets its energy requirement around 41% by indigenous gas, 19% by oil, and 37% by hydro electricity. Coal and nuclear contribution to energy supply is limited to 0.16% and 2.84% respectively with a vast potential for growth. The Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA) is vigorously carrying out feasibility studies and engineering designs for various hydropower projects with accumulative generation capacity of more than 25000 MW. Most of these studies are at an advance stage of completion. After the completion of these projects the installed capacity would rise to around 42000 MW by the end of the year 2020. Pakistan has been blessed with ample water resources but could store only 13% of the annual flow of its rivers. -

A Study of Project Management Plan of Dasu Hydropower Project

CAPITAL UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, ISLAMABAD A Study of Project Management Plan of Dasu Hydropower Project Executed by Water and Power Development Authority, Government of Pakistan by Mahad Ali Zafar A project submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Science in the Faculty of Management & Social Sciences Department of Management Sciences 2019 i Copyright c 2019 by Mahad Ali Zafar All rights reserved. No part of this project may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of the author. ii First of all, I thank ALLAH Almighty who is the most merciful and beneficent. ALLAH created us and showed us a correct pathway. ALLAH always secretes sins and protects us from social troubles. I also dedicate my study to my parents. CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL A Study of Project Management Plan of Dasu Hydropower Project Executed by Water and Power Development Authority, Government of Pakistan by Mahad Ali Zafar MPM-171005 RESEARCH PROJECT EXAMINING COMMITTEE S. No. Examiner Name Organization (a) Internal Examiner Mr. Nasir Rasool CUST, Islamabad (b) Project Supervisor Dr. Umar Nawaz Kayani CUST, Islamabad Dr. Umar Nawaz Kayani Project Supervisor April, 2019 Dr. Sajid Bashir Dr. Arshad Hassan Head Dean Dept. of Management Sciences Faculty of Management & Social Sciences April, 2019 April, 2019 iv Author's Declaration I, Mahad Ali Zafar (Registration No: MPM-171005), hereby state that my MS project titled \A Study of Project Management Plan of Dasu Hy- dropower Project Executed by Water and Power Development Author- ity, Government of Pakistan" is my own work and has not been submitted previously by me for taking any degree from Capital University of Science and Technology, Islamabad or anywhere else in the country/abroad. -

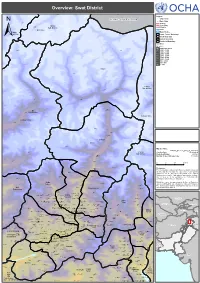

Swat District !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties.