Livelihoods and Food Security Trust Fund Annual Report 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6 July 2021 1 6 July 21 Gnlm

STRIVE TO SHOW CULTURE AND MANNER OF NATION AND NATIONALS TO TOURISTS PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Union Minister for Construction inspects road, bridge Myanmar-Thai experts on workers construction works in Ayeyawady, Magway regions discuss migrant workers’ affairs PAGE-3 PAGE-5 Vol. VIII, No. 78, 12th Waning of Nayon 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Tuesday, 6 July 2021 Five-Point Road Map of the State Administration Council 1. The Union Election Commission will be reconstituted and its mandated tasks, including the scrutiny of voter lists, shall be implemented in accordance with the law. 2. Effective measures will be taken with added momentum to prevent and manage the COVID-19 pandemic. 3. Actions will be taken to ensure the speedy recovery of businesses from the impact of COVID-19. 4. Emphasis will be placed on achieving enduring peace for the entire nation in line with the agreements set out in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. 5. Upon accomplishing the provisions of the state of emergency, free and fair multiparty democratic elections will be held in line with the 2008 Constitution, and further work will be undertaken to hand over State duties to the winning party in accordance with democratic standards. Ayeyawady sees developing transport infrastructures YEYAWADY Region was Myaungmya were parts of the is unknown when it was called. once included in the Mon Mon Nya region. Despite being Only the name “RaMaNya” was ANya region, one of three an area where significant Myan- first found in the very ancient Mon regions—Mon Ti, Mon Sa mar kings did not establish, the chronicles of Siho (Chapter and Mon Nya. -

Mansi Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census KACHIN STATE, BHAMO DISTRICT Mansi Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Kachin State, Bhamo District Mansi Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1: Map of Kachin State, showing the townships Mansi Township Figures at a Glance 1 Enumerated Population 52,945 2 Total Population Estimated Population 31,243 Population males 26,156 (49.4%) Population females 26,789 (50.6%) Percentage of urban population 15.4% Area (Km2) 2,932.8 3 Population density (per Km2) 28.7 persons Median age 24.9 years Number of wards 4 Number of village tracts 20 Number of private households 10,554 Percentage of female headed households 32.2% Mean household size 4.9 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 32.3% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 63.3% Elderly population (65+ years) 4.4% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 57.9 Child dependency ratio 50.9 Old dependency ratio 7.0 Ageing index 13.8 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 98 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 89.3% Male 91.8% Female 86.9% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 2,118 4.0 Walking 765 1.4 Seeing 1,063 2.0 Hearing 790 1.5 Remembering 811 1.5 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship -

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin and Northern Shan States

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! (1 June 2014) ! !( ! ! ! MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin and ! northern! Shan States ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Hpan Hkaing (2) ! ! !Man No Yat Bawt (Wa Ram) Jar Wan ! Ma Li Sar ! Yat Bawt (Li Suu) Ma Kan Dam !War Sar ! !Ta Se Htu ! ! !Pa Da Myar (Nam Bu Yam) Ah Let Dam! Da Zan Yae Ni To ! ! ! ! Man Pan! Nam Shei Ma Aun Nam! ! Mon Ngo ! Ta Kwar Auk San Kawng ! ! Nam Sa Tham ! ! Sin! Lon Dam! (2) ! ! ! ! Ma Li Di ! ! Sa Dup! Ah Tan Mar Meit Shi Dee! Par Hkee! ! ! ! Nam Say ! ! NAWNGMUN ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Htan Htawt! Ma Hti Sut Nam Bon! ! ! Man Khut !Ba Bawt ! Mu Don (2) Hta War Dam ! Htu San !Tan Zein Chan La War Tar ! ! !Nam Hkam ! Pin Sin Nam Din ! Ma Jawt Wawt! ! Lon Yein War Hkan ! ! ! ! ! !Shein Kan Kha La Me War Ji ! Ma Ran Hta Zin Htan Nawng Tan In Waing Bawt Ka Khin ! Dar Bang Auk ! ! ! ! Ba Zu Ah Ri Lein Ma Rein ! ! Ri Zum! ! !Tar Lang ! Nam Tar Lel Ran Za Kon ! ! Nawng Tan(Jubily)! ! Puta-O ! In Bu Bawt Ran Nam Min Zar !Rar War Haw ! ! Ma Lein Kan ! ! Nam Ton Khu ! INDIA ! ! Ni Nar War Ji Ah Lang Ga Ye Bang Hta Mae !( ! ! Ma Hkaung Dam! ! Ji Bon 8 ! Lin Kawng! ! ! 36 Hton Li ! CHINA ! Hpan Don ! Lar Tar Tee !( ! ! Nam Par ! ! Ya Khwi Dan ! ! ! San Dam Chi Htu HpanNam Yaw Di Yar Hpar Dee Mu Lar Aun! Htang Ga ! ! Zi Aun ! ! Machanbaw ! ! ! ! ! Ta Kwar Dam Yi Kyaw Di ! Chun Ding Wan Sam ! Lang No (2) ! ! ! ! Nin Lo Dam ! Pa La Na ! Auk Par Zei Mu Lar Haung Shin Mway Yang ! ! ! 37 ! Lar Kar Kaw ! Sa Ye Hpar ! Ah Day Di Hton Hpu! ! ! ! Khi Si Di !Hpar Tar Hpat -

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin and Northern Shan States(As of 30 Nov 2017)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin and northern Shan States (as of 30 Nov 2017) La War Tar Htu San Lon Yein Nam Din Shein Kan Kha Tan Zein Chan Ka Khin ☇88 Ri Zum Ba Zu Nam Ton Khu 89 Ah Lang Ga Ye Bang Hton Li Hta Mae Nam Par Htang Ga Puta-OYi Kyaw Di Machanbaw San Dam Ah Day Di 87 Shin Mway Yang INDIA Hpu Lum Ri Dam Khin Le Zar Lar Hpat Ma Di Ding Chet INDIA Nam Au Dam Ra Man Chun Chum Ding Lar Tee Mone Yat In Ga Ding Sar Tar Kar Shin Naw Ga CHINA Ma Jang Ga Chi Nan Zee Dam Tan Gyar Shar Lar Ga Khaunglanhpu Puta-O Ah Ku Machanbaw Wi Nin Zan Yaw Tone Kun Sun Wa Det Ka Htan Pan Hpi Zaw BAN- Git Jar Ga GLA- In Zi Ran Ye Htan La Ja DESH Hkawng Lang Tsum Pi Yang Khaunglanhpu Ran Zain Nam Ching Man Jar Tan In Htut Ga Naw Yan Hta Hpone In Dang Ga Ma Shawt Hku Hpa Lar LAOS In Khan Sin Ran Nay Pyi Taw Lon Wan Hpon Kyan Ta Hton Kyin Kan Dar Dum Gan Shin Bway Yang Hting Lu Yang Ta Seik Sha Chyum Jahtung U Ma Ngar Yar In Gaw Ma Dam Ga Bum Wan Bay Ta Hket Tanai In Hkai Pa Kyon Ga of Lut Mong Yang Nawng Yar Jar Ran La Kin Hka Hkauk Bengal Ta Ron Aum Hta Ka Dawt Ding Yawt 155 La Jar Bum Sumprabum ☇☇156 Maw We 93 Wa Yoke THAILAND ☇ Sai Ran La Mai Hpan Sar Chu Deik Hpar In Ta Ga Lu War Li Ga Pa Net Sha Gu Ga La Yaung Wa Se Tsawlaw Gulf Su Yang Ma Dan Tu La Mon Pa Din of In Hpyin Ga Ma Wun U Ma 96 Za Nan Kha Aum Ka Tu Martaban 94 ☇ Sumprabum Ma Sa Hkan ☇ Pa Kawt Naw Lang Bum Rong 95 Tanai La Ja Bum ☇ Wa Baw Kya Nar Yang In Koi ☇97 La Myan Ka Htaung Mai Khun (Mont Hkawm) Zan Yu Yit Yaw Bum Rong Da Gum Ga Hting Baing Hpu Shar Rong Ngaw Yaw Jaw Sa Kyi Dee Nam Ma Kha Ka Htang Tu Gum Lang List of IDP Sites Ahr Hlyin Sha Re U Ma Ku Maw Adan Ga Ba Wu Khu Nam Hkan Par Khin Dam Taung Hpum Ye Ga Wa Hau Sa Du Law Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Kying Ma Ga Su Yang Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster Nam Hpyet Yang Bum Rong Au Ga Tsawlaw Hka Rong based on update of 30 November 2017 Pin Laung Adan Ga Yin Kyang Wa Rar Ga Hpa Wa Ting Kawk Gat Rai Yang Ka Nawt Ka Ring Ga Htan Dung But Hkar No. -

Burma Briefer

Λ L T S E Λ N B U R M A BN 2014/2003: Edited September 19, 2014 DEVELOPMENTS AFTER THE 2013 UNGA RESOLUTION The Burmese authorities have failed to implement most of the recommendations from previous United Nations General INSIDE Assembly (UNGA) resolutions, in particular Resolution 1 2015 ELECTIONS 68/242, adopted in 2013. In some areas, the situation has 2 MEDIA FREEDOMS RESTRICTED deteriorated as a result of deliberate actions by the 3 ARBITRARY HRD ARRESTS authorities. This briefer summarizes developments on the 4 OTHER HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS ground with direct reference to key paragraphs of the 4 Torture and sexual violence resolution. 5 Land confiscation 5 WAR AND PEACE TALKS The authorities have either failed or refused to protect 6 PERSECUTION OF ROHINGYA vulnerable populations from serious human rights violations, 6 Discriminatory legislation or pursued essential legislative and institutional reforms, effectively blocking Burma’s progress towards genuine 6 Pre-existing laws and policies democracy and national reconciliation. This has been partly 7 Failure to respond to communal violence due to an assumption that the UNGA resolution will either be 7 Hate speech and incitement to violence canceled or severely watered down as a trade-off for smaller 7 1.2 MILLION PEOPLE EXCLUDED concessions. FROM CENSUS 8 SITUATION DIRE IN ARAKAN STATE So far, 2014 has been marred by an overall climate of APPENDICES impunity that has seen a resurgence of media repression, the ongoing sentencing of human rights defenders, an increase in a1 I: 158 new arrests and imprisonments the number of land ownership disputes, and ongoing attacks a14 II: Contradictory ceasefire talks on civilians by the Tatmadaw in Kachin and Shan States a15 III: 122 clashes in Kachin, Shan States amid nationwide ceasefire negotiations. -

IDP Sites in Kachin State As of 31 December 2020

MYANMAR IDP sites in Kachin State As of 31 December 2020 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Da Hun Dam Nay Pyi Taw LAOS Ma Ding Ta Su Htu Hta On Dam Da Zun Dam THAILAND Ga Waing Shing Wan Dam INDIA Nawngmun Pannandin Ah Li Awng Khu Ti Htu Ku Shin Kaw Leit Htu List of IDP Sites Lang Naing Pan Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Zi Yar Dam Ma Li Rein Ka San Khu Chei Kan Da Bu Dam Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster based on Khar Lam Baw Sar Dee Hton Dam Hpan Khu Nam Pan Dan Lon Khar Hkawng Lang update of 31 December 2020 Ah Wet Dam Nam Ro -2 San Dan Ah Wi Wan Kun Lin Gat Htu Ma Yi Nawngmun No. State Township IDP Site IDPs Lon Kan Jar Wan Man No Ka San Dan Tan Wi 1 AD-2000 Tharthana Compound 915 War Sar Ta Se Htu Da Zan 2 Aung Thar Church 50 3 Htoi San Church 220 Nam Say Mon Ngo Sa Dup Ba Bawt Nam Din 4 Bhamo IDPs in Host 906 Htu San Ma Jawt Wawt Lon Yein War Hkan 5 Lisu Boarding-House 650 Ka Khin Ba Zu 6 Phan Khar Kone 339 92 Nawng Tan In Waing Bawt Ran Nam 7 Robert Church 3,876 Nam Ton Khu 93 Ah Lang Ga Ye Bang Hton Li Ji Bon 8 Chipwi KBC camp 871 Nam Par Htang Ga 9 Chipwi Lhaovao Baptist Church (LBC) 892 Puta-OYi Kyaw Di Machanbaw San Dam Zi Aun 91 Shin Mway Yang 10 Pan Wa (Host IDP) 20 Hpar Tar Inn Lel Yan Hpu Lum Hton Hpu Zar Lee 11 AG Church, Hmaw Si Sa 378 Ri Dam Ding Chet 12 AG Church, Maw Wan 62 Hpat Ma Di Mee Kaw Lo Po Te 13 Baptist Church, Hmaw Si Sar(Lon Khin) 225 Mone Yat Chum Ding 14 Chin Church, Seik Mu 32 In Ga Ding Sar Tar Kar Kun Sai Yang Tar Saw Nee 15 Dhama Rakhita, Nyein Chan Tar Yar Ward(Lon Khin) 382 Shin Naw Ga Ma Jang Ga Chi Nan Zee Dam 16 Hlaing Naung Baptist 155 Tan Gyar MachanbawShar Lar Ga 17 Hmaw Wan, Anglican 14 Zee Kone 18 Hpakant Baptist Church, Nam Ma Hpit 520 Ah KuKhaunglanhpu 19 Karmaing RC Church 53 20 Lawa RC Church 242 Wi Nin 21 Lawng Hkang Shait Yang Camp ( Lel Pyin) 678 Puta-O Kun Sun Zan Yaw Tone Hpakant 22 Lisu Baptist Church, Maw Shan Vil,. -

NPT Booklet Cover 6Feb Combined

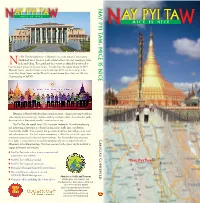

AY PYI TA PYI TAW NAY N M I C E I S N I C E W AY PYI TA N M I C E I S N I C E W , MICE IS NICE ay Pyi Taw the capital city of Myanmar, sits at the centre of the country which itself sits at the cross roads of Asia between two vast emerging powers, India and China. The capital and the country are admirably positioned to becomeN major players in the near future. Already since the regime change in 2010 Myanmar has re-staked its claim on the world stage. 2013 saw the hosting of the South East Asian Games and the World Economic Forum (East Asia) and 2014 the Chairmanship of ASEAN. Myanmar is blessed with abundant natural resources, a large and young workforce, wide-ranging investment opportunities, and a government that is determined to guide the country to a democratic, market-orientated economy. Nay Pyi Taw, the capital since 2005, has green credentials. It combines pleasing and interesting architecture, good landscaping and no traffic jams or pollution. Seated in the middle of the country, this government city is a hub with good air, road and rail connections. For the business community it offers first rate hotels, up to date convention centres and a fine new sports stadium. For the traveller there are many Caroline Courtauld Caroline local sights to enjoy and it is an excellent jumping-off point to explore the rest of Myanmar’s rich cultural heritage. For these reasons it is the ‘green’ city from which to engage in business and tourism. -

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin State (As of 31 October 2018)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin State (as of 31 October 2018) BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Nay Pyi Taw LAOS Da Hun Dam Ma Ding THAILAND Ta Su Htu Hta On Dam Da Zun Dam Ga Waing Shing Wan Dam INDIA Nawngmun Pannandin Ah Li Awng List of IDP Sites Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Khu Ti Htu Ku Shin Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster based on Kaw Leit Htu Lang Naing Pan update of 31 October 2018 Zi Yar Dam Ma Li Rein Ka San Khu Chei Kan Da Bu Dam Khar Lam Baw Sar Dee Hton Dam Hpan Khu No. State Township IDP Site IDPs Nam Pan Dan Lon Khar Hkawng Lang Ah Wet Dam Nam Ro -2 1 AD-2000 Tharthana Compound 1,166 San Dan Ah Wi Wan Nawngmun Kun Lin Gat Htu Ma Yi 2 Aung Thar Church 52 3 Host Families 928 Lon Kan Jar Wan Man No Ka San Dan Tan Wi 4 Htoi San Church 234 War Sar Ta Se Htu Da Zan 5 Lisu Boarding-House 774 Bhamo Nam Say Mon Ngo Sa Dup 6 Mu-yin Baptist Church 57 Ba Bawt Nam Din 7 Nant Hlaing Church 76 Htu San Ma Jawt Wawt Lon Yein War Hkan 8 Phan Khar Kone 764 Ka Khin Ba Zu 98 Nawng Tan In Waing Bawt 9 Robert Church 4,010 Ran Nam Nam Ton Khu 99 Ah Lang Ga Ye Bang Ji Bon 10 Yoe Kyi Monastery 63 Hton Li Nam Par 11 Chipwi KBC camp 804 Machanbaw Htang Ga San Dam Puta-OYi Kyaw Di 12 Lhaovao Baptist Church (LBC) 847 Zi Aun 97 Shin Mway Yang Chipwi Hpar Tar 13 Pan Wa 273 Inn Lel Yan Hpu Lum Hton Hpu Zar Lee Ri Dam 14 Saw Zam 165 Ding Chet Hpat Ma Di Mee Kaw 15 5 Ward RC Church(lon Khin) 335 Mone Yat Lo Po Te Chum Ding 16 AG Church, Hmaw Si Sa 374 In Ga Ding Sar Tar Kar Kun Sai Yang Tar Saw Nee 17 AG Church, Maw Wan 83 Shin Naw Ga 18 Baptist Church, Hmaw Si Sar(Lon Khin) 226 Ma Jang Ga Chi Nan Zee Dam Tan Gyar 19 Chin Church, Seik Mu 31 MachanbawShar Lar Ga Zee Kone 20 Dhama Rakhita, Nyein Chan Tar Yar Ward(Lon Khin) 375 Ah KuKhaunglanhpu 21 Hlaing Naung Baptist 136 22 Hmaw Wan, Anglican 14 Wi Nin Puta-O Kun Sun Zan Yaw Tone 23 Hpakant Baptist Church, Nam Ma Hpit 529 24 Karmaing RC Church 63 25 Lawa RC Church 187 Wa Det Khaunglanhpu Hpi Zaw Git Jar Ga 26 Hpakant Lawng Hkang Shait Yang Camp ( Lel Pyin) 665 27 Lisu Baptist Church, Maw Shan Vil,. -

IDP Sites in Kachin State (As of 31 August 2018)

MYANMAR: IDP Sites in Kachin State (as of 31 August 2018) BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH Nay Pyi Taw LAOS Da Hun Dam Ma Ding THAILAND Ta Su Htu Hta On Dam Da Zun Dam Ga Waing Shing Wan Dam INDIA Nawngmun Pannandin Ah Li Awng List of IDP Sites Data provided by the Camp Coordination and Khu Ti Htu Ku Shin Camp Management (CCCM) Cluster based on Kaw Leit Htu Lang Naing Pan update of 31 August 2018 Zi Yar Dam Ma Li Rein Ka San Khu Chei Kan Da Bu Dam Khar Lam Baw Sar Dee Hton Dam Hpan Khu No. State Township IDP Site IDPs Nam Pan Dan Lon Khar Hkawng Lang Ah Wet Dam Nam Ro -2 1 AD-2000 Tharthana Compound 1,161 San Dan Ah Wi Wan Nawngmun Kun Lin Gat Htu Ma Yi 2 Aung Thar Church 51 3 Host Families 928 Lon Kan Jar Wan Man No Ka San Dan Tan Wi 4 Htoi San Church 225 War Sar Ta Se Htu Da Zan 5 Lisu Boarding-House 774 Bhamo Nam Say Mon Ngo Sa Dup 6 Mu-yin Baptist Church 57 Ba Bawt Nam Din 7 Nant Hlaing Church 76 Htu San Ma Jawt Wawt Lon Yein War Hkan 8 Phan Khar Kone 747 Ka Khin Ba Zu 98 Nawng Tan In Waing Bawt 9 Robert Church 3,702 Ran Nam Nam Ton Khu 99 Ah Lang Ga Ye Bang Ji Bon 10 Yoe Kyi Monastery 63 Hton Li Nam Par 11 Chipwi KBC camp 799 Machanbaw Htang Ga San Dam Puta-OYi Kyaw Di 12 Lhaovao Baptist Church (LBC) 837 Zi Aun 97 Shin Mway Yang Chipwi Hpar Tar 13 Pan Wa 273 Inn Lel Yan Hpu Lum Hton Hpu Zar Lee Ri Dam 14 Saw Zam 165 Ding Chet Hpat Ma Di Mee Kaw 15 5 Ward RC Church(lon Khin) 336 Mone Yat Lo Po Te Chum Ding 16 AG Church, Hmaw Si Sa 374 In Ga Ding Sar Tar Kar Kun Sai Yang Tar Saw Nee 17 AG Church, Maw Wan 83 Shin Naw Ga 18 Baptist Church, Hmaw Si Sar(Lon Khin) 226 Ma Jang Ga Chi Nan Zee Dam Tan Gyar 19 Chin Church, Seik Mu 31 MachanbawShar Lar Ga Zee Kone 20 Dhama Rakhita, Nyein Chan Tar Yar Ward(Lon Khin) 377 Ah KuKhaunglanhpu 21 Hlaing Naung Baptist 136 22 Hmaw Wan, Anglican 14 Wi Nin Puta-O Kun Sun Zan Yaw Tone 23 Hpakant Baptist Church, Nam Ma Hpit 514 24 Karmaing RC Church 59 25 Lawa RC Church 203 Wa Det Khaunglanhpu Hpi Zaw Git Jar Ga 26 Hpakant Lawng Hkang Shait Yang Camp ( Lel Pyin) 662 27 Lisu Baptist Church, Maw Shan Vil,. -

21 May 2021 1 21 May 21 Gnlm

DON’T FORGET USEFULNESS OF COTTON SUITABLE FOR MYANMAR PEOPLE PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL State Sangha Maha Nayaka Committee Chairman Sayadaw, Responsibility, loyalty needed members of Sangha comfort monks sitting for 73rd Tipitakadhara for public healthcare at hospitals: Tipitakakovida Selection Examination MoHS PAGE-2 PAGE-4 Vol. VIII, No. 32, 11th Waxing of Kason 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Friday, 21 May 2021 Taxes must be levied in a fair manner for the State and the people: Senior General State Administration Council Chairman Senior General Min Aung Hlaing presides over the SAC Management Committee Meeting 7/2021 in Nay Pyi Taw on 20 May 2021. FFORTS will be made cies, and relevant ministries All the people need to use rongs, blankets and mosquito clothes for domestic use. Like- for resuming the need to implement the policies. the domestic products with nets. Some kinds of threads are wise, domestic pharmaceutical EState-owned garment Hence, the Union ministers patriotic spirit. All need to imported from foreign coun- industries need to produce a factories and cotton ginning can meet departmental staff control the trade harming the tries. The government must sufficient volume of common factories which were recent- on their trips for fulfilling the domestic production and local give assistance for the culti- medicines to reduce imported ly suspended from operating needs. Moreover, the minis- economy. Mandalay Region and vation of cotton plants so as to medicines and decrease for- production of clothes in order tries should coordinate with dry zones in Myanmar are en- produce threads. Local indus- eign exchange spending. -

Number of Tourist Arrivals to Myanmar Will Reach 0.5 Million to 1.8 Million in 2023: Vice-Senior General

CHOOSE OPTIONS TO NURTURE PLANTED SAPLINGS OR NOT PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Facemask wearing campaigns must be raised in Myanmar chairs 2nd regional workshop on stay-at-home townships: Vice-Senior General reviewing and updating ASEAN CCSTP PAGE-3 PAGE-6 Vol. VIII, No. 73, 7th Waning of Nayon 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Thursday, 1 July 2021 Five-Point Road Map of the State Administration Council 1. The Union Election Commission will be reconstituted and its mandated tasks, including the scrutiny of voter lists, shall be implemented in accordance with the law. 2. Effective measures will be taken with added momentum to prevent and manage the COVID-19 pandemic. 3. Actions will be taken to ensure the speedy recovery of businesses from the impact of COVID-19. 4. Emphasis will be placed on achieving enduring peace for the entire nation in line with the agreements set out in the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement. 5. Upon accomplishing the provisions of the state of emergency, free and fair multiparty democratic elections will be held in line with the 2008 Constitution, and further work will be undertaken to hand over State duties to the winning party in accordance with democratic standards. Number of tourist arrivals to Myanmar will reach 0.5 million to 1.8 million in 2023: Vice-Senior General THE National Tourism Devel- opment Central Committee held the first meeting at Horizon Lake View Hotel in Nay Pyi Taw yes- terday, with an address by Chair- man of the Central Committee Vice-Chairman of the State Ad- ministration Council Deputy Com- mander-in-Chief of Defence Ser- vices Commander-in-Chief (Army) Vice-Senior General Soe Win. -

The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census KACHIN STATE, MYITKYINA DISTRICT Waingmaw Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census KACHIN STATE, MYITKYINA DISTRICT Waingmaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Kachin State, Myitkyina District Waingmaw Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Kachin State, showing the townships Waingmaw Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 106,366 2 Population males 52,698 (49.5%) Population females 53,668 (50.5%) Percentage of urban population 20.7% Area (Km2) 3,625.8 3 Population density (per Km2) 29.3 persons Median age 23.1 years Number of wards 5 Number of village tracts 26 Number of private households 19,780 Percentage of female headed households 32.0% Mean household size 5.1 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 34.8% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 60.5% Elderly population (65+ years) 4.7% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 65.1 Child dependency ratio 57.4 Old dependency ratio 7.7 Ageing index 13.5 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 98 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 83.2% Male 87.4% Female 79.4% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 7,788 7.3 Walking 2,592 2.4 Seeing 4,283 4.0 Hearing 2,945 2.8 Remembering 2,467 2.3 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 57,560