Joanne Lipman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lowdown on Showdowns: We Don't Look 100 and Neither Do You

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Lowdown on Showdowns: PilotingWe around Don’t Partisan Look Divides 100 in Immigration, and Neither Infrastructure, Do You:and Industry 2020 Perspectives from the Pioneers of CEO Leadership Forums Washington, DC | March 13, 2018 The Roosevelt Hotel New York | December 17 - 18, 2019 PRESENTING SPONSORS The AmericanLEADERSHIP PARTNERS Colossus: The Best of Times and the Worst of Times? The Yale Club of New York City & The New York Public Library | June 12 - 13, 2018 LEADERSHIP PARTNERS We Don’t Look 100 and Neither Do You: 2020 Perspectives from the Pioneers of CEO Leadership Forums The Roosevelt Hotel New York | December 17–18, 2019 Agenda Host: Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld, Senior Associate Dean, Yale School of Management The Changed Cultural Portfolio of Leadership 7 OPENING COMMENTS Carla A. Hills, U.S. Trade Representative (1989-1993); 5th U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Reem Fawzy, Founder & CEO, Rimo Tours Group & Pink Taxi Egypt Farooq Kathwari, Chairman, President & CEO, Ethan Allen Kay Koplovitz, Founder, USA Networks; Managing Partner, Springboard Growth Capital Beth Van Duyne, Mayor (2011-2017), Irving, Texas Kerwin Charles, Dean, Yale School of Management Joanne Lipman, Distinguished Fellow, Princeton University; Former Editor, USA TODAY Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO & National Director, Anti-Defamation League Manuel Dorantes, Strategic Advisor, Vatican’s Dicastery for Communication Jonathan Mariner, Founder & President, TaxDay; Retired EVP & CFO, Major League Baseball Eileen Murray, Co-Chief Executive Officer, Bridgewater Associates Greg Fischer, Mayor, Louisville, Kentucky RESPONDENTS Katherine E. Fleming, Provost, New York University Laura R. Walker, Former President & CEO, New York Public Radio Kristin Decas, CEO & Port Director, The Port of Hueneme Elizabeth DeMarse, Former Chair, President & CEO, TheStreet, Inc. -

JOANNE LIPMAN Joanne Lipman Is

JOANNE LIPMAN Joanne Lipman is the best-selling author of That's What She Said: What Men Need to Know (and Women Need to Tell Them) About Working Together. One of the nation's leading journalists, she is a CNBC contributor and most recently was chief content officer of Gannett and editor-in-chief of USA TODAY and the USA TODAY NETWORK, comprising the flagship title and 109 other news organizations including the Detroit Free Press, the Cincinnati Enquirer, and the Arizona Republic. In that role, she oversaw more than 3,000 journalists and led the organization to three Pulitzer Prizes. Ms. Lipman began her career as a reporter at The Wall Street Journal, ultimately rising to Deputy Managing Editor - the first woman to attain that post - and supervising coverage that earned three Pulitzer Prizes. While at the Journal, she created Weekend Journal and Personal Journal and oversaw creation of the paper's Saturday edition. She subsequently was founding Editor-in-Chief of Conde Nast Portfolio and Portfolio.com, which won National Magazine and Loeb Awards. Lipman is a frequent television commentator, seen on ABC, CNN, MSNBC, NBC, CNBC, and CBS, among others, and her work has appeared in publications including The New York Times, Time, Fortune, Newsweek, and Harvard Business Review. She is also co-author, with Melanie Kupchynsky, of the critically acclaimed musical memoir, Strings Attached. A winner of the Matrix Award for women in communications, Lipman is also a member of the Yale University Council, the Council on Foreign Relations, and is an International Media Leader for the World Economic Forum as well as a member of the Knight Foundation Commission on Truth, Media and Democracy. -

Yalewomen Award for Excellence Working Toward Gender Equity Panel Discussion and Award Dinner March 7, 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award Anita F

YaleWomen, Inc., in partnership with the Yale Alumni Association, presents YaleWomen Award for Excellence Working Toward Gender Equity Panel Discussion and Award Dinner March 7, 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award Anita F. Hill ’80 JD Catherine E. Lhamon ’96 JD Ann Olivarius ’77, ’86 MBA, ’86 JD Impact Award Araceli Campos ’99 BA C’Ardiss Gardner Gleser ’08 BA Kamala Lopez BA Rebecca Reichmann Tavares ’78 BA Vera Wells ’71 BA Platinum Sponsor National Press Club, Washington D.C. Dear Yale Alums and Friends, We are thrilled to welcome you to the YaleWomen Award for Excellence celebration! When YaleWomen was founded in 2011 – following the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the coeducation of Yale College and the 140th anniversary of the coeducation of the Graduate & Professional Schools – it was a “big idea” full of possibilities. During these first eight years, we have grown – notably as an all-volunteer organization -- in many different ways: in numbers and complexity, driven by the clarity and focus that come with being mission-centered and market-smart. And the importance of our work has become more evident. This year’s Award for Excellence celebration exemplifies the power of individual women to catalyze change and to inspire us to exert ourselves to take action on issues we believe in. The opportunity for all of us here today to honor Anita F. Hill ’80 JD, Catherine E. Lhamon ’96 JD, and Ann Olivarius ’77, ’86 MBA, ’86 JD as Lifetime Achievement awardees; and Araceli Campos ’99 BA, C’Ardiss Gardner Gleser ’08 BA, Kamala Lopez BA, Rebecca Reichmann Tavares ’78 BA, and Vera Wells ’71 BA as our inaugural Impact awardees, is both extraordinary and humbling. -

Minutes of the American Society of Newspaper Editors

1513 MINUTES – BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING – NOVEMBER 9, 2001 Minneapolis The meeting originally scheduled for Sept. 21, but postponed due to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, began with board members, legal counsel, and staff present. The committee chairs joined them later in the morning. Board members attending: Tim J. McGuire, editor, Star Tribune, Minneapolis, President Diane H. McFarlin, publisher, Sarasota (Fla.) Herald-Tribune, Vice President Peter K. Bhatia, executive editor, The Oregonian, Portland, Secretary – Creating Newspapers’ Future in Tough Times Karla Garrett Harshaw, editor, Springfield (Ohio) News-Sun, Treasurer Susan C. Deans, assistant managing editor/Weekends, Rocky Mountain News, Denver Frank M. Denton, editor, Wisconsin State Journal, Madison Charlotte H. Hall, managing editor, Newsday, Melville, N.Y. – The American Editor, co-chair Pamela J. Johnson, Leadership & Management Faculty, The Poynter Institute, St. Petersburg, Fla. Edward W. Jones, editor, The Free Lance-Star, Fredericksburg, Va. Wanda S. Lloyd, executive director, The Freedom Forum Institute for Newsroom Diversity, Nashville, Tenn. Robert G. McGruder, executive editor, Detroit Free Press Gregory L. Moore, managing editor, The Boston Globe Rick Rodriguez, executive editor, The Sacramento (Calif.) Bee – Readership Issues Paul C. Tash, editor and president, St. Petersburg (Fla.) Times – Leadership David A. Zeeck, executive editor, The News Tribune, Tacoma, Wash. – Convention Program Committee chairs attending: Susan Bischoff, deputy managing editor, Houston Chronicle – Education for Journalism Byron E. Calame, deputy managing editor, The Wall Street Journal, New York – Craft Development Debra Flemming, editor, The Free Press, Mankato, Minn. – Small Newspapers Carolina Garcia, managing editor, San Antonio Express-News – Diversity Anders Gyllenhaal, executive editor, The News & Observer, Raleigh, N.C. -

Eyes on Janesville When Speaker Ryan Was Ready to Endorse, His Hometown Newspaper Broke the Story

FEATURE: Meet the Woodville Leader, Sun-Argus. Page 2 THETHE June 9, 2016 BulletinBulletinNews and information for the Wisconsin newspaper industry All eyes on Janesville When Speaker Ryan was ready to endorse, his hometown newspaper broke the story BY JAMES DEBILZEN vative agenda. Communications Director Schwartz said the news t wasn’t a scoop in the tra- was unex- ditional telling of newsroom pected. On Ilore. There were no anony- Wednesday, mous sources, cryptic messages June 1, opin- or meetings with shadowy fig- ion editor ures in empty parking garages. Greg Peck Regardless, editor Sid was contacted Schwartz of The Gazette in Sid Schwartz by Ryan’s of- Angela Major photo | Janesville said it was “fun to fice to discuss Courtesy of The Gazette have a national news item that the publi- we got to break,” referencing cation of a ABOVE: House Speaker Paul being the first media outlet to column about Ryan discusses his endorse- announce the Speaker of the “Republican ment of Donald Trump and his House was endorsing the pre- unity and the policy vision with members of sumptive Republican candidate House policy The Gazette’s editorial Board for the presidency. agenda.” on Friday, June 3. Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Janes- “We didn’t LEFT: The endorsement ville, announced in a column really know story broke on The Gazette’s first published on The Gazette’s what we website, www.gazettextra. website on June 2 that he would Greg Peck were getting,” com, on Thursday afternoon. vote for businessman Donald Schwartz Friday’s front page carried the Trump in November, lending said. -

Why Learn Toplay MUSIC?

Health Benefits Music and the Arts are Vital Elements of the Curriculum Why “We don’t see these kinds of biological changes Visit NAMMFoundation.org to learn the benefits of Learn in people who are just listening to music, who music education; how to support music programs in are not playing an instrument. I like to give schools; and to join the SupportMusic Coalition, a to Play the analogy that you’re not going to become national network of music education advocates. physically fit just by watching sports.” MUSIC? Sources – NINA KRAUS, TIME 16 1. Harris Interactive, 2006. 2. NAMM Foundation and Grunwald Associates LLC (2015).Striking a Chord: The Public’s Hopes and Beliefs for K–12 Music Education in Photo Credit: Kim Floyd Photography the United States: 2015. 3. NAMM Foundation and Grunwald Associates LLC (2015). Striking a Chord: The Public’s Hopes and Beliefs for K–12 Music Education in the United States: 2015. 4. Woodruff Carr K, W.-S.T.,Tierney A, Strait D, Kraus N. , Beat synchronization and speech encoding in preschoolers: A neural synchrony framework for language development. , in Association for Research in Otolaryngology Symposium. 2014: San Diego, CA. 5. Peter Greene,“Stop ‘defending’ music education,” The Huffington Post, June 11, 2015. 6. Joanne Lipman, “Is Music the Key to Success?” The New York Times, October 13, 2013. 7. Strait, D.L. and N. Kraus, Biological impact of auditory expertise across the life span: musicians as a model of auditory learning. Hearing Research, 2013; Strait, D.L. and N. Kraus, Can you hear me now? Musical training shapes functional brain networks for selective auditory attention and hearing speech in noise. -

The Lowdown on Showdowns: the American Colossus

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Lowdown on Showdowns: Piloting around PartisanThe Divides American in Immigration, Colossus: Infrastructure, and Industry The Best of Times and the Worst of Times? Washington, DC | March 13, 2018 The Yale Club of New York City & The New York Public Library | June 12 - 13, 2018 PRESENTING SPONSORS The AmericanLEADERSHIP PARTNERS Colossus: The Best of Times and the Worst of Times? The Yale Club of New York City & The New York Public Library | June 12 - 13, 2018 LEADERSHIP PARTNERS The American Colossus: The Best of Times and the Worst of Times? The Yale Club of New York City & The New York Public Library June 12-13, 2018 Agenda Welcome & Overview 7 Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld, Senior Associate Dean, Yale School of Management Shining Lamp by the Golden Door: Opportunity and Obstacle 9 OPENING REMARKS Joanne Lipman, Former Editor, USA TODAY; Author, That’s What She Said James Fallows, National Correspondent, The Atlantic; Author, Our Towns COMMENTS Jeffrey D. Sachs, Director, Center for Sustainable Development, Columbia University Adam F. Falk, President, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Farooq Kathwari, Chairman, President & CEO, Ethan Allen Manuel Dorantes, Strategic Advisor, Vatican Secretariat for Communication Caryl M. Stern, President & CEO, UNICEF US Toni Harp, Mayor, New Haven, Connecticut Tom Tait, Mayor, Anaheim, California Greg Fischer, Mayor, Louisville, Kentucky Nasser J. Kazeminy, Founder & Chairman, NJK Holding Corporation; Chairman, Ellis Island Foundation Stephen K. Benjamin, Mayor, Columbia, South Carolina Michael A. Leven, Retired President, Las Vegas Sands; Chair & CEO, Georgia Aquarium Brian Gallagher, President & CEO, United Way Worldwide © 2016 Chief Executive Leadership Institute. All rights reserved. 2 The American Colossus: The Best of Times and the Worst of Times? The Yale Club of New York City & The New York Public Library June 12-13, 2018 Shining a Light Abroad: Deep Thoughts on the Deep State at Home 11 OPENING REMARKS James R. -

Infomercials, Deceptive Advertising and the Federal Trade Commission W.H

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 19 | Number 3 Article 19 1992 Infomercials, Deceptive Advertising And the Federal Trade Commission W.H. Ramsay Lewis Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the Consumer Protection Law Commons Recommended Citation W.H. Ramsay Lewis, Infomercials, Deceptive Advertising And the Federal Trade Commission, 19 Fordham Urb. L.J. 853 (1992). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol19/iss3/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFOMERCIALS, DECEPTIVE ADVERTISING AND THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION I. Introduction "Infomercials" 1 are a new form of television advertising based on program-length, direct response marketing. A typical infomercial presentation takes the form of a half hour talk show program devoted exclusively to the product being marketed, accompanied by toll-free telephone numbers to order the product. 2 Often, the program is en- hanced with celebrity guests, a studio audience and demonstrations of the product. Recently, there has been growing concern among consumers, broadcasters and the Federal Trade Commission ("FTC" or "the Commission") that infomercials may be a form of deceptive advertis- ing.' Complaints about infomercials range from objections to the hard sell tactics,4 to the apprehension that. products will not work for buyers at home as well as they have on television.' The greatest fear is that the public will mistake the paid advertisement with its paid endorsements and pre-arranged demonstrations for an actual, objec- tive talk show.6 These problems are further complicated by the talk- show magazine style format of the programs and current require- ments of only minimal identification of the paid nature of the pro- gram. -

From Hot Wheels to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: the Evolution of the Definition of Program Length Commercials on Children's Television

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 359 566 CS 508 197 AUTHOR Colby, Pamela A. TITLE From Hot Wheels to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Evolution of the Definition of Program Length Commercials on Children's Television. PUB DATE Apr 93 NOTE 35p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Broadcast Education Association (Las Vegas, NV, April 12-16, 1993). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Historical Materials (060) Information Analyses (070) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Television; *Commercial Television; *Federal Regulation; Government Role; Media Research; *Programing (Broadcast); *Television Commercials IDENTIFIERS *Educational Issues; Federal Communications Commission; Hot Wheels Cars (Game); Media Government Relationship; *Program Length Commercials ABSTRACT From 1969 to 1993 the definition of program length commercials has not been consistent. The FCC's first involvement with program length commercials was in 1969 when "Hot Wheels," a cartoon based on Mattel Corporation's Hot Wheels cars, was alleged to be nothing more than a 30 minute commercial. The FCC made no formal ruling but did develop a vague definition of a program length commercial. In 1971, the FCC issued its first Notice of Inquiry and Notice of Proposed Rule Making regarding commercial content in children's programming. Response was tremendous, and the FCC co-cluded that broadcasters have a special obligation to serve the unique needs of children. No formal rulings were made by the FCC, who wanted the broadcast industry to regulate itself. A 1978 Notice of Inquiry only restated previous guidelines. In 1983, the FCC wanted to deregulate children's television. while Congress started a major effort to adopt legislation. -

Annual Report 2009-2010

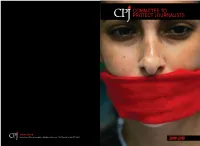

COMMITTEE TO PROTECT JOURNALISTS www.cpj.org Committee to Protect Journalists • 330 Seventh Avenue, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10001 2009-2010 Committee to Protect Journalists I LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR The Committee to Protect Journalists promotes media freedom worldwide. We take action when journalists are censored, jailed, kidnapped, or killed for their work. CPJ is an independent, nonprofit organization founded in 1981. REUTERS/YURIKO NAKAO REUTERS/YURIKO Dear Friends: This is an incredibly exciting time to be defending independent journalists and free expression. Digital technologies are enabling new forms of journalism and contributing to a global culture of greater open- ness and transparency. There are more people practicing journalism than ever before. The new technologies, however, can be a boon to repressive governments—allowing for surveillance and censorship on an unprecedented scale. In 2009, half of all imprisoned journalists were targeted for work published online. The Internet is also transforming the news business, which has enormous implications for our work. As media companies eliminate foreign bureaus and cut staff positions, freelancers are on the front- lines of reporting the news around the world. Freelance journalists are especially vulnerable to arrest and intimidation because they often lack the legal and financial support that large news organizations can provide to staffers. Journalists of all stripes increasingly work independently—that is to say, alone. These trends make CPJ’s work even more vitally important. When journalists are imprisoned, we campaign for their release. When journalists are forced into exile, we help support them. When jour- nalists are killed for their work, we demand justice. -

The American Empire and Its Media

edia COUNCILon., FOREIGN Est. 1954 Est.1921 Est.1973 RELATIONS THE TRllATERAl COMMISSION . ....�"!"'. & 1 4 n5 146 17 18 158 FOREIGN AFFAIRS FT 0 NY � • PBS. DAILY•NEWS NEWS 250 135 11/C CH c ,I;. fill You 19/C 20/C 100/C 117/B/D/T 118/C 160/C 171/C 172/C [iJ 136 149r7!il ID 26 c c c � ,� -- 2/C '''.it- Ill clHJ ·�D 188/C 189/T 101/C 102/C 119/C 120/C/T PIXt\R 161/C 162/C 181/D 182/C II 72 � 183/C 184/C 13/C 14/C 21/C c 173/C 174/C 36 [9] a -.� ���.a. c .. ts/c 49/C ii. 85/C 86/B/C 104/B/C 121/M 122/C 163/C � 138 - 151 El !Al 60/D 61/B/C • ,. • c T 28 [al ' " c 37 �j llf8'Jil ....... Ji..i. ... ./ 87/C 88/C 124/C a c 50/C 51/C 165/C 166/C 29 3/C � c U..N...l.· ""'..•..•..s...A. L. v �· THE TII\IES 38n -r.: 126/C B/C�,- 75� 175/C 176/C '• " 190/D/T - 127/C 39r7""" 76 154 Sl(Y c c (3N c 'l'heNewVorlr. iA Review of Books' AP i!limcs 64/C 65/C 93/T 111/8/C 112/C/T 129/C Journalists and media executives: New York Daily News and U.S. News & World Report 1: Mortimer B. Zuckerman, publisher [ Slate 2: Jacob Weisberg, group editor I The Nation 3: Katrina VandenHeuvel, publisher [ Foreign Affairs 4: James F. -

Dec 5, 2018 1-5Pm 4 Th Annual

BOSTON CONVENTION & EXHIBITION CENTER DEC 5, 2018 1-5PM 4 TH ANNUAL N AC E HE AW HO ST AD H R LE LE S E E C NNE LIPM A AN JO JOIN THE CONVERSATION! #MASSWOMEN 1 WORKPLACE SUMMIT SPONSORS 2 MACONFERENCEFORWOMEN.ORG CREATING WORKPLACES THAT WORK FOR EVERYONE Welcome to the 4th Annual Massachusetts Conference for Women Workplace Summit! This Summit is designed for men and women who are in mid-level manager roles—and want to be part of creating workplaces that work for everyone. It will address some of today’s most pressing real-world challenges around gender, communication, trust, and equity in the workplace. Get ready to: • Learn from 6 of the nation’s top strategists • Engage with your peers • Gain practical strategies to maximize your professional success and bottom line results. You will leave with tools and advice to help you: • Collaborate and work together without fear or mistrust • Improve communications and relationships within your teams • Breakthrough invisible barriers to gender partnership • Reach your biggest collective potential yet! We can do better—together! JOIN THE CONVERSATION! #MASSWOMEN 3 PROGRAM 1:00 PM GENERAL SESSION BALLROOM EAST WELCOME CAROL FULP, president & CEO, The Partnership, Inc. and @MassWomen board member @carol_fulp EMCEE ALEXANDRA TAUSSIG, senior vice president, Fidelity Investments KEYNOTE Navigating the Workplace in a Post #MeToo Era…Now What? JOANNE LIPMAN, one of the nation’s leading journalists, former editor-in-chief of USA TODAY , and author, That’s What She Said @joannelipman The world has changed in the wake of the #MeToo movement. What comes next? Joanne Lipman, bestselling author of That’s What She Said and former Editor in Chief of USA TODAY, offers real-world solutions and a path forward.