Unfinished Sympathy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 CITIES 4 PROJECTS Mercedes, İstanbul ONS İncek, Ankara Batı Dental, Ankara Köker, Ankara

Work Life, Architecture, Culture and Art December 2015 TIME MOMENTS OF TIME Faruk Malhan IN BETWEEN ART, CRAFT AND DESIGN Dilek Öztürk PRODUCTION OF TIME Özlem Sert 2 CITIES 4 PROJECTS Mercedes, İstanbul ONS İncek, Ankara Batı Dental, Ankara Köker, Ankara www.koleksiyoninternational.com Contents Prologue Koray Özsoy ‘Time’ is one of the words that we Speaking of time; maybe the Looking at micro level; we can All these varieties make us mention all are assumed to know very well famous painting ‘The Persistence define time as a plane formed by about a major ‘change’ from daily until it turns into a difficult matter to of Memory’ by Dali comes first to moments. A fourth dimension to things, needs to permanent habits explain when some one asks the our minds. Although the artist in his width, height and length in space! and traces that would settle for 26 real meaning behind. Referring to unique way that he was inspired But it cannot be undone and years, eras and influence societies. WORKS & NOTES basic dictionaries; time is described by the Camambert cheese melting controlled; there is only one direction Just like the creative-destructive as “a duration, period which uses under the sun on a hot August day, to go: forward (for now). Time is effects of time driving the change Salon 6 the regular and periodic celestial this piece of art is interpreted as a composed of subjective marks, or in objects and spaces... IN BETWEEN TIME, Alper Derinboğaz CRAFT AND DESIGN events of past, present and future”. protest against the concept of time ‘moments’, created individually by However; we need to be reading that is unquestionable, strict and each of us as we go forward. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

My Love of Music

My Love of Music My name is Gail and I want to share about some of the music and stories of my life. My love of music starting when my Dad's cousin gave the family loads of new records, probably 'falling out a lorry'. Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Animals, Dusty Springfield – I loved playing the records on the radiogram - and a radiogram is a piece of furniture that combined a radio and record player. I loved Tamla Motown, Four Tops, Little Stevie Wonder. Georgie Fame, and on TV watching Ready, Steady, Go, Juke Box Jury. I was listening to the 'Pirates Radio' – Radio Caroline, Radio London, and Radio Luxembourg. The songs that remind me of the 70s I lived in Muswell Hill, and I discovered West End clubs – The Roaring Twenties, La Valbonne, Birds Nest, Gullivers, The Pourbelle, Anabelle, Tramps, Ronnie Scotts, Blues parties, etc., etc., etc. Reggae, Disco, Soca, Jazz and Soul. I worked as a PA for a record company and later worked with the owner of West End clubs and I met a long list of ‘celebrities.’ Stevie Wonder, Bob Marley, Luddy from the Pioneers, The Drifters, George McCrea, The Harlem Globetrotters, Hot Chocolate, Viola Wills, Sex Pistols, Nina Simone, etc. etc. – and we all go to the ‘Kandy Box’ a basement club in Kingsley Street, after-work or show 2 am – 7 am. (even CJ Carlos and Q Club (with Smokey Joe) on Sunday night Marvin Gaye- What’s Going On An album in 1971 helped people to open their minds. About racial, the Vietnam War, drug abuse, poverty and ecological. -

Mark Scheme H409/01 Media Messages June 2019

GCE Media Studies H409/01: Media messages Advanced GCE Mark Scheme for June 2019 Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations OCR (Oxford Cambridge and RSA) is a leading UK awarding body, providing a wide range of qualifications to meet the needs of candidates of all ages and abilities. OCR qualifications include AS/A Levels, Diplomas, GCSEs, Cambridge Nationals, Cambridge Technicals, Functional Skills, Key Skills, Entry Level qualifications, NVQs and vocational qualifications in areas such as IT, business, languages, teaching/training, administration and secretarial skills. It is also responsible for developing new specifications to meet national requirements and the needs of students and teachers. OCR is a not-for-profit organisation; any surplus made is invested back into the establishment to help towards the development of qualifications and support, which keep pace with the changing needs of today’s society. This mark scheme is published as an aid to teachers and students, to indicate the requirements of the examination. It shows the basis on which marks were awarded by examiners. It does not indicate the details of the discussions which took place at an examiners’ meeting before marking commenced. All examiners are instructed that alternative correct answers and unexpected approaches in candidates’ scripts must be given marks that fairly reflect the relevant knowledge and skills demonstrated. Mark schemes should be read in conjunction with the published question papers and the report on the examination. © OCR 2019 H409/01 Mark Scheme June 2019 Annotations used in the detailed Mark Scheme (to include abbreviations and subject-specific conventions) Stamp Description Blank page N/A Highlight Off page comment Tick Cross Unclear Omission mark Terminology Example/Reference Accurate Lengthy narrative Expandable vertical wavy line 1 H409/01 Mark Scheme June 2019 SUBJECT–SPECIFIC MARKING INSTRUCTIONS Introduction Your first task as an Examiner is to become thoroughly familiar with the material on which the examination depends. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

WAR GAMES Any Genre Is Somewhat of a Damocles Sword

OFF THE FLOOR OFF THE FLOOR Books, art, movies, etc... Words: KIRSTY ALLISON as anonymous gate-holders to all things trip-hop. much observers of the culture around them as art WAR GAMES Any genre is somewhat of a Damocles sword. The makers. So this feeds into a rich loop of creativity. This new Massive Attack book is well group’s continuing sonic warfare mirrors Bristol’s “Adam Curtis is a BBC documentary film-maker worth investigating... port, bashing with all the waves of the world’s who has challenged television quite deeply. They tides, from slavery to silks, spices and the roots/ first worked together for the 2013 Manchester history of St Pauls. We speak to Melissa Chemam, International Festival. Curtis called it a ‘gilm’: whose encyclopaedic new book Out Of The Comfort gig + film. I’m not sure it fits. The visuals and the Zone has just been translated into English from music create something very special, but it is an her French original. additional layer and, much as Curtis’ messages “For me, Massive Attack are a living organism,” are powerful, overall, it only works because it’s Chemam says. “They emerged as a collective in Massive Attack.” 1988, with 3D, Daddy G and Mushroom, but the group wouldn’t be complete without their guest Punk was an influence on Massive Attack, vocalists. First came Horace Andy, Shara Nelson you say in the book: “In 1980, Bristol was and rapper Tricky. But the latter two left, so particularly sensitive to tensions. On 2nd suddenly the ever-evolving collective became not April, riots erupted in St Pauls, when the police only a concept, but a trademark. -

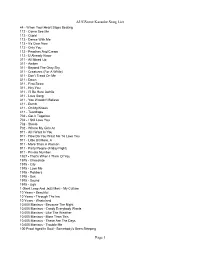

Augsome Karaoke Song List Page 1

AUGSome Karaoke Song List 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 112 - Come See Me 112 - Cupid 112 - Dance With Me 112 - It's Over Now 112 - Only You 112 - Peaches And Cream 112 - U Already Know 311 - All Mixed Up 311 - Amber 311 - Beyond The Gray Sky 311 - Creatures (For A While) 311 - Don't Tread On Me 311 - Down 311 - First Straw 311 - Hey You 311 - I'll Be Here Awhile 311 - Love Song 311 - You Wouldn't Believe 411 - Dumb 411 - On My Knees 411 - Teardrops 702 - Get It Together 702 - I Still Love You 702 - Steelo 702 - Where My Girls At 911 - All I Want Is You 911 - How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 - Little Bit More, A 911 - More Than A Woman 911 - Party People (Friday Night) 911 - Private Number 1927 - That's When I Think Of You 1975 - Chocolate 1975 - City 1975 - Love Me 1975 - Robbers 1975 - Sex 1975 - Sound 1975 - Ugh 1 Giant Leap And Jazz Maxi - My Culture 10 Years - Beautiful 10 Years - Through The Iris 10 Years - Wasteland 10,000 Maniacs - Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs - Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me 100 Proof Aged In Soul - Somebody's Been Sleeping Page 1 AUGSome Karaoke Song List 101 Dalmations - Cruella de Vil 10Cc - Donna 10Cc - Dreadlock Holiday 10Cc - I'm Mandy 10Cc - I'm Not In Love 10Cc - Rubber Bullets 10Cc - Things We Do For Love, The 10Cc - Wall Street Shuffle 112 And Ludacris - Hot And Wet 12 Gauge - Dunkie Butt 12 Stones - Crash 12 Stones - We Are One 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Verlegt Auf Den 30.06.2021 - Die Tickets Bleiben Gültig!

Verlegt auf den 30.06.2021 - die Tickets bleiben gültig! Aufgrund der behördlich festgelegten Verbote für Großveranstaltungen, müssen die beiden Konzerte von Massive Attack, die für Juni 2020 geplant waren, ins Jahr 2021 verschoben werden. Alle bereits gekauften Tickets behalten ihre Gültigkeit für die Nachholtermine. ----------------------------- Massive Attack im Juni 2021 für zwei Shows in Deutschland (verlegt aus 2020) Songs wie „Teardrop“, „Unfinished Sympathy“, „Karmacoma“ oder auch das noch relativ junge „The Spoils“ sind zeitlose Klassiker. Damals wie heute sorgen die kraftvollen, schweren und cleveren Tracks von Massive Attack für einen Schauer, der gekommen ist, um zu bleiben. Dass dem so ist, liegt auch an den Live-Shows der vergangenen Jahre. Robert „3D“ Del Naja und Grantley Evan Marshall aka Daddy G – die einzig verbliebenen Gründungsmitglieder der Band aus Bristol – veröffentlichen zwar nur sehr ausgewählt neue Musik, schaffen es mit ihren Liveshows aber immer noch und immer wieder, das Publikum umzublasen und ihren Songs neue Kraft zu geben. Ein Gig von Massive Attack ist nämlich weit mehr als ein schnödes Konzert, sondern eher ein Bastard aus Konzert, Medienkunst- Performance und Statement zur Zeit. Für jeden Song schlagen sie in ihren Visuals eine Brücke in die Jetztzeit, transportieren eine Message, zeigen Haltung. Dabei frischen sie ihre Line-Ups stets mit wechselnden Gastsänger*innen auf – oder holen wie im Falle der Young Fathers vor einigen Jahren - auch einfach mal die Vorband in ihre Shows. Langweilig wird es mit ihnen also nie – und das wird sich auch im Sommer 2021 nicht ändern, wenn sie erneut für zwei Gigs in Deutschland Station machen. 20.06.2021 Berlin - Max-Schmeling-Halle* | verlegt vom 10.06.2020 aus dem Velodrom (*Achtung: neues Venue) 30.06.2021 Düsseldorf - Mitsubishi Electric HALLE | verlegt vom 09.06.2020 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

FEATURES BEST of 2019 Lynne Cooke Nicole Eisenman Jack

DECEMBER 2019 COLUMNS FEATURES Film: Best of 2019 28 158 BEST OF 2019 John Waters, Amy Taubin, James Quandt, Lynne Cooke Melissa Anderson, J. Hoberman Nicole Eisenman Jack Bankowsky Music: Best of 2019 42 Naima J. Keith Jace Clayton, Polly Watson, Byron Coley, Susanne Pfeffer Sarah Hennies Ara Osterweil Johanna Fateman The Year in Performance 55 Christina Li Jennifer Krasinski Christopher Glazek Ruth Estévez Books: Best of 2019 64 Sohrab Mohebbi Terry Castle, Pamela M. Lee, Gary Lutz, Imani Perry, 29 Ken Okiishi Douglas Crase, Harry Dodge, Elvia Wilk, Mac Wellman, Miriam Katzeff Zeynep Çelik Alexander, Marina Vishmidt, Henriette Huldisch Marwa Helal, Morgan Bassichis 192 THE YEAR IN FRIENDSHIP The Artists’ Artists 78 David Velasco Art & Language, Natalie Ball, Danica Barboza, Hannah Black Ellen Berkenblit, Andrea Blum, DeForrest Brown Jr., Greg Zuccolo and Sarah Michelson Judy Chicago, TM Davy, Andrej Dubravsky, Roe Ethridge, Hamishi Farah, Ellie Ga, Nicholas Galanin, REVIEWS Beatriz González, Rodney Graham, Hugh Hayden, Elizabeth Jaeger, Xylor Jane, Jane Kaplowitz, 212 Andy Campbell on Nayland Blake Helmut Lang, Monica Majoli, Marlene McCarty, 213 Kaelen Wilson-Goldie on Helen Frankenthaler Alan Michelson, Ima-Abasi Okon, Greg Parma Smith, Suellen Rocca, Pieter Schoolwerth, Tuesday Smillie, 214 From New York, Buffalo, Chicago, Austin, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Toronto, Mexico City, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Valeska Soares, Patrick Staff, Diamond Stingily, 88 Christine Sun Kim, Sarah Sze, Bernadette Van-Huy London, Dublin, Paris, Rome, Zurich, Vienna, Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Warsaw, Prague, Athens, Istanbul, Mumbai, Kolkata, Nanjing, and Auckland 180 Cover: Nan Goldin, Picnic on the Esplanade, 1 Boston (detail), 1973, Cibachrome, 27 ⁄2 × 40". -

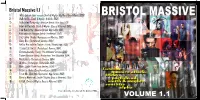

Bristol Massive

Bristol Massive 1.1 1) Intro (edited short version, Smith & Mighty:: Big World Small World, 2000) 2) Walk on By (Smith & Mighty:: Dj Kicks, 2001) 3) Unfinished Sympathy (Massive Attack:: Blue Line, 1991) 4) Down in Rwanda (Smith & Mighty:: Bass is Maternal, 1995) 5) Five Man Army (Massive Attack: Blue Lines, 1991) 6) Karmacoma (Massive Attack: Protection , 1996) 7) Overcome (Tricky:: Maxinquaye, w/Martina, 1995) 8) Glory Box (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 9) Hell is Around the Corner (Tricky:: Maxinquaye, 1995) 10) It Could Be Sweet (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 11) Christiansands (Tricky:: Pre-millennial Tension, 1996) 12) Three (Massive Attack:: Protection/ feat. Nicollete, 1994) 13) Mysterions (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 14) All Mine (Portishead:: Portishead, 1998) 15) Rain (Alpha:: Come From Heaven, 1998) 16) Delaney (Alpha:: ComeFromHeaven, 1998) 17) Trust Me (Roni Size/Reprazent:: New Forms, 1998) 18) Bass is Maternal (Smith & Mighty, Bass is Maternal, 1995) 19) U-Dub (Smithy & Mighty, Bass is Maternal, 1995) tracks selected by Jerry Saturn @ The Masthead, 2004 Bristol Massive 1.2 1) Closer (Smith & Mighty:: Bass is Maternal, 1995) 2) Jungle Man Corner (Smith & Mighty:: Bass is Maternal, 1995) 3) Spying Glass (Massive Attack:: Protection, w/ Horace Andy, 1996) 4) No Justice (Smith & Mighty:: Big World, Small World, 2000) 5) Be Thankful For What You Got (Massive Attack:: Blue Lines, 1991) 6) Sour Times (Portishead:: Dummy, 1994) 7) With (Alpha:: ComeFromHeaven, 1998) 8) Undenied (Portishead:: Portishead, 1998) 9) Move You Run (Smith & Mighty:: -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

The Ultimate Playlist This List Comprises More Than 3000 Songs (Song Titles), Which Have Been Released Between 1931 and 2018, Ei

The Ultimate Playlist This list comprises more than 3000 songs (song titles), which have been released between 1931 and 2021, either as a single or as a track of an album. However, one has to keep in mind that more than 300000 songs have been listed in music charts worldwide since the beginning of the 20th century [web: http://tsort.info/music/charts.htm]. Therefore, the present selection of songs is obviously solely a small and subjective cross-section of the most successful songs in the history of modern music. Band / Musician Song Title Released A Flock of Seagulls I ran 1982 Wishing 1983 Aaliyah Are you that somebody 1998 Back and forth 1994 More than a woman 2001 One in a million 1996 Rock the boat 2001 Try again 2000 ABBA Chiquitita 1979 Dancing queen 1976 Does your mother know? 1979 Eagle 1978 Fernando 1976 Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! 1979 Honey, honey 1974 Knowing me knowing you 1977 Lay all your love on me 1980 Mamma mia 1975 Money, money, money 1976 People need love 1973 Ring ring 1973 S.O.S. 1975 Super trouper 1980 Take a chance on me 1977 Thank you for the music 1983 The winner takes it all 1980 Voulez-Vous 1979 Waterloo 1974 ABC The look of love 1980 AC/DC Baby please don’t go 1975 Back in black 1980 Down payment blues 1978 Hells bells 1980 Highway to hell 1979 It’s a long way to the top 1975 Jail break 1976 Let me put my love into you 1980 Let there be rock 1977 Live wire 1975 Love hungry man 1979 Night prowler 1979 Ride on 1976 Rock’n roll damnation 1978 Author: Thomas Jüstel -1- Rock’n roll train 2008 Rock or bust 2014 Sin city 1978 Soul stripper 1974 Squealer 1976 T.N.T.