'Easter, 1916': Yeats's First World War Poem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Harmony of the Race, Each Individual Should Be

http://www.englishworld2011.info/ WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS / 2019 For the harmony of the race, each individual should be the expression of an easy & ample interpenetration of the male & female temperaments—free of stress Woman must become more responsible for the child than man— Women must destroy in themselves, the desire to be loved— The feeling that it is a personal insult when a man transfers his attentions from her to another woman The desire for comfortable protection instead of an intelligent curiosity & courage in meeting & resisting the pressure of life sex or so called love must be reduced to its initial element, honour, grief, sentimentality, pride & consequently jealousy must be detached from it. Woman for her happiness must retain her deceptive fragility of appearance, combined with indomitable will, irreducible courage, & abundant health the outcome of sound nerves— Another great illusion that woman must use all her introspective clear-sightedness & unbiassed bravery to destroy—for the sake of her self respect is the impurity of sex the realisation in defiance of superstition that there is nothing impure in sex—except in the mental attitude to it—will constitute an incalculable & wider social regeneration than it is possible for our generation to imagine. 1914 1982 WILLIAM BUTLER YEATS 1865-1939 William Butler Yeats was born to an Anglo-Irish family in Dublin. His father, J. B. Yeats, had abandoned law to take up painting, at which he made a somewhat precar- ious living. His mother came from the Pollexfen family that lived near Sligo, in the west of Ireland, where Yeats spent much of his childhood. -

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This Poem Deals with the Dublin Rebellion Of

W. B. Yeats Easter 1916 This poem deals with the Dublin Rebellion of Easter 1916 which is believed to have been the beginning of modern Ireland, in spite of its immediate failure. Yeats was in Dublin when it happened, and though at first he was against the violence and the bloodshed that accompanied it and he thought the sacrifice of its leaders wasteful, he sympathized with the rebels when sixteen of them were executed. In Stanza One the poet describes the previous lives of the rebels to suggest that they were average or normal citizens who sacrificed their lives for the sake of Irish independence. They were normal Irish people with "vivid faces" and he used to meet them with a nod of the head or saying polite meaningless words. However, he shared with them the love of Ireland: Be certain that they and I But lived where motely is worn The word "motely" means colourful dress which symbolizes Irish people. The stanza ends with "a terrible beauty is born" which may allude to the Birth of Hellen of Troy, Maud Gonne and Ireland because Irish independence will be accompanied by violence and bloodshed. In Stanza Two the poet mentions some of the significant rebels b eginning with "that woman" which refers to Maud Gonne, the most beautiful woman in Ireland according to Ye ats who was with the rebels; she was imprisoned in England after the rising but she escaped to Dublin in 1918. Because of her interest in Irish independence and in politics and argument, her beautiful voice became shrill. -

Echoes of the Orient: the Writings of William Quan Judge

ECHOES ORIENTof the VOLUME I The Writings of William Quan Judge Echoes are heard in every age of and their fellow creatures — man and a timeless path that leads to divine beast — out of the thoughtless jog trot wisdom and to knowledge of our pur- of selfish everyday life.” To this end pose in the universal design. Today’s and until he died, Judge wrote about resurgent awareness of our physical the Way spoken of by the sages of old, and spiritual inter dependence on this its signposts and pitfalls, and its rel- grand evolutionary journey affirms evance to the practical affairs of daily those pioneering keynotes set forth in life. HPB called his journal “pure Bud- the writings of H. P. Blavatsky. Her dhi” (awakened insight). task was to re-present the broad This first volume of Echoes of the panorama of the “anciently universal Orient comprises about 170 articles Wisdom-Religion,” to show its under- from The Path magazine, chronologi- lying expression in the world’s myths, cally arranged and supplemented by legends, and spiritual traditions, and his popular “Occult Tales.” A glance to show its scientific basis — with at the contents pages will show the the overarching goal of furthering the wide range of subjects covered. Also cause of universal brotherhood. included are a well-documented 50- Some people, however, have page biography, numerous illustra- found her books diffi cult and ask for tions, photographs, and facsimiles, as something simpler. In the writings of well as a bibliography and index. William Q. Judge, one of the Theosophical Society’s co-founders with HPB and a close personal colleague, many have found a certain William Quan Judge (1851-1896) was human element which, though not born in Dublin, Ireland, and emigrated lacking in HPB’s works, is here more with his family to America in 1864. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems

W. B. Yeats Selected Poems Compiled by Emma Laybourn 2018 This is a free ebook from www.englishliteratureebooks.com It may be shared or copied for any non-commercial purpose. It may not be sold. Cover picture shows Ben Bulben, County Sligo, Ireland. Contents To return to the Contents list at any time, click on the arrow ↑ before each poem. Introduction From The Wanderings of Oisin and other poems (1889) The Song of the Happy Shepherd The Indian upon God The Indian to his Love The Stolen Child Down by the Salley Gardens The Ballad of Moll Magee The Wanderings of Oisin (extracts) From The Rose (1893) To the Rose upon the Rood of Time Fergus and the Druid The Rose of the World The Rose of Battle A Faery Song The Lake Isle of Innisfree The Sorrow of Love When You are Old Who goes with Fergus? The Man who dreamed of Faeryland The Ballad of Father Gilligan The Two Trees From The Wind Among the Reeds (1899) The Lover tells of the Rose in his Heart The Host of the Air The Unappeasable Host The Song of Wandering Aengus The Lover mourns for the Loss of Love He mourns for the Change that has come upon Him and his Beloved, and longs for the End of the World He remembers Forgotten Beauty The Cap and Bells The Valley of the Black Pig The Secret Rose The Travail of Passion The Poet pleads with the Elemental Powers He wishes his Beloved were Dead He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven From In the Seven Woods (1904) In the Seven Woods The Folly of being Comforted Never Give All the Heart The Withering of the Boughs Adam’s Curse Red Hanrahan’s Song about Ireland -

A League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

THE ROLE OF THE GAELIC LEAGUE THOMAS MacDONAGH PATRICK PEARSE EOIN MacNEILL A League of extraordinary gentlemen Gaelic League was breeding ground for rebels, writes Richard McElligott EFLECTING on The Gaelic League was The Gaelic League quickly the rebellion that undoubtedly the formative turned into a powerful mass had given him nationalist organisation in the movement. By revitalising the his first taste of development of the revolutionary Irish language, the League military action, elite of 1916. also began to inspire a deep R Michael Collins With the rapid decline of sense of pride in Irish culture, lamented that the Easter Rising native Irish speakers in the heritage and identity. Its wide was hardly the “appropriate aftermath of the Famine, many and energetic programme of time for memoranda couched sensed the damage would be meetings, dances and festivals in poetic phrases, or actions irreversible unless it was halted injected a new life and colour DOUGLAS HYDE worked out in similar fashion”. immediately. In November 1892, into the often depressing This assessment encapsulates the Gaelic scholar Douglas Hyde monotony of provincial Ireland. the generational gulf between delivered a speech entitled ‘The Another significant factor participation in Gaelic games. cursed their memory”. Pearse the romantic idealism of the Necessity for de-Anglicising for its popularity was its Within 15 years the League had was prominent in the League’s revolutionaries of 1916 and the Ireland’. Hyde pleaded with his cross-gender appeal. The 671 registered branches. successful campaign to get Irish military efficiency of those who fellow countrymen to turn away League actively encouraged Hyde had insisted that the included as a compulsory subject would successfully lead the Irish from the encroaching dominance female participation and one Gaelic League should be strictly in the national school system. -

Microfilm Publication M617, Returns from U.S

Publication Number: M-617 Publication Title: Returns from U.S. Military Posts, 1800-1916 Date Published: 1968 RETURNS FROM U.S. MILITARY POSTS, 1800-1916 On the 1550 rolls of this microfilm publication, M617, are reproduced returns from U.S. military posts from the early 1800's to 1916, with a few returns extending through 1917. Most of the returns are part of Record Group 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office; the remainder is part of Record Group 393, Records of United States Army Continental Commands, 1821-1920, and Record Group 395, Records of United States Army Overseas Operations and Commands, 1898-1942. The commanding officer of every post, as well ad commanders of all other bodies of troops such as department, division, brigade, regiment, or detachment, was required by Army Regulations to submit a return (a type of personnel report) to The Adjutant General at specified intervals, usually monthly, on forms provided by that office. Several additions and modifications were made in the form over the years, but basically it was designed to show the units that were stationed at a particular post and their strength, the names and duties of the officers, the number of officers present and absent, a listing of official communications received, and a record of events. In the early 19th century the form used for the post return usually was the same as the one used for regimental or organizational returns. Printed forms were issued by the Adjutant General’s Office, but more commonly used were manuscript forms patterned after the printed forms. -

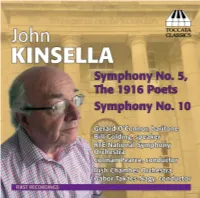

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

The Oldskull Necronomicon

Sample file 2 | P a g e Sample file CASTLE OLDSKULL ~ LOV1 KENT DAVID KELLY P a g e | 3 CASTLE OLDSKULL FANTASY ROLE-PLAYING SUPPLEMENT LOV1 THE OLDSKULL NECRONOMICON By KENT DAVID KELLY (DARKSERAPHIM) THE NECRONOMICON SERIES (I ~ III) IS COLLECTIVELY ILLUSTRATED BY HEINRICH ALDEGREVER, ULISSE ALDROVANDI, FILIPPO BALBI, FRANCESCO BALLESIO, SampleJAN CHRISTIAN BIERPFAFF, WILLIAM BLAKE,file CASTLE OLDSKULL ~ LOV1 KENT DAVID KELLY 4 | P a g e LEON BONNAT, HIERONYMUS BOSCH, FERDINAND MAX BREDT, AGNOLO BRONZINO, ALFRED CHATAUD, HARRY CLARKE, HERBERT COLE, HERMAN DAVID SALOMON CORRODI, JEAN DELVILLE, GUSTAVE DORE, HENRY J. FORD, EUGENE FROMENTIN, JOHANN HEINRICH FUSSLI, EUGENE-ALEXIS GIRARDET, HENRY GILLARD GLINDONI, FREDERIC GOODALL, CARL HAAG, ARTHUR HACKER, ERNST HAECKEL, ALBRECHT VON HALLER, JOHN HUSS, THEODOR KITTELSEN, MAX KLINGER, JULES LAURENS, EDWIN LONG, AUGUSTE MAYER, LUC-OLIVIER MERSON, JOHN MILFORD, KAY NIELSEN, ERNEST NORMAND, BERNARDINO PARENZANO, ADRIAEN PIETERSZ, HOWARD PYLE, EDOUARD RIOU, DAVID ROBERTS, ALBERT ROBIDA, MARCEL ROUX, HERBERT GUSTAV SCHMALZ, SIDNEY SIME, CARL SPITZWEG, ELIHU VEDDER, VASILY VERESHCHAGIN, SampleET ALII file CASTLE OLDSKULL ~ LOV1 KENT DAVID KELLY P a g e | 5 WONDERLAND IMPRINTS 2017 ONLY THE FINEST WORKS OF FANTASY ~ O s r Copyright © 2017 Kent David Kelly. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced without the written permission of the copyright holder, Kent David Kelly. (Document Version 1.0) Please feel welcome to contact the author at [email protected] with comments, questions, requests, recommendations and greetings. And thank you for reading! “Only the Finest Works of Fantasy” Sample file CASTLE OLDSKULL ~ LOV1 KENT DAVID KELLY 6 | P a g e HIC SVNT DRACONES HERE THERE BE DRAGONS CASTLE OLDSKULL (“Old School”) is a well-regarded, system neutral line of supplements designed for use in Fantasy Role-Playing Games (FRPGs). -

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, Delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29Th September, 2016

Speech on Joseph Mary Plunkett, delivered at Stonyhurst College Thursday, 29th September, 2016 As Ireland commemorates the centenary of the Easter Rising — the event that sparked a popular movement towards independence from the United Kingdom one hundred years ago this year — the tendency has been to focus, perhaps somewhat simplistically, on the history of the participants and of the event itself. But in the Easter Rising we find that history was born in literature, and reality in text. With the Celtic Revival in its latter days by 1916, and the rediscovery of national heroes from ancient myth, such as Cuchulain, permeating the popular imagination, it should not seem too surprising that a headmaster, a university professor, and an assortment of poets saw themselves — and became — the champions of Irish freedom. As the historian Standish O’Grady prophetically declared in the late nineteenth century: ‘We have now a literary movement, it is not very important; it will be followed by a political movement that will not be very important; then must come a military movement that will be important indeed.’1 The ideas crafted in the study took fire in the streets in 1916, and Joseph Mary Plunkett — poet, aesthete, military strategist, and rebel — offers a fascinating study of this nexus of thought and action. Plunkett is often mythologized as the hero who wed his sweetheart on the eve of his execution in May 1916, but I would like to broaden this narrative by framing this evening’s talk around not one but three women who profoundly shaped Plunkett’s life, and who are the subject of many poems he wrote, some of which I would like to share with you this evening. -

World War I in 1916

MAJOR EVENTS AFFECTING THE COUNTY IN 1916 In a front line trench, France, World War I (Library of Congress, Washington) World War I in 1916 When war was declared on 4 August 1914, there were already over 25,000 Irishmen serving in the regular British Army with another 30,000 Irishmen in the reserve. As most of the great European powers were drawn into the War, it spread to European colonies all over the world. Donegal men found that they were fighting not only in Europe but also in Egypt and Mesopotamia as well as in Africa and on ships in the North Sea and in the Mediterranean. 1916 was the worst year of the war, with more soldiers killed this year than in any other year. By the end of 1916, stalemate on land had truly set in with both sides firmly entrenched. By now, the belief that the war would be ‘over by Christmas’ was long gone. Hope of a swift end to the war was replaced by knowledge of the true extent of the sacrifice that would have to be paid in terms of loss of life. Recruitment and Enlisting Recruitment meetings were held all over the County. In 1916, the Department of Recruiting in Ireland wrote to Bishop O’Donnell, in Donegal, requesting: “. that recruiting meetings might with advantage be held outside the Churches . after Mass on Sundays and Holidays.” 21 MAJOR EVENTS AFFECTING THE COUNTY IN 1916 Men from all communities and from all corners of County Donegal enlisted. They enlisted in the three new Army Divisions: the 10th (Irish), 16th (Irish) and the 36th (Ulster), which were established after the War began. -

Deirdre Toomey

Margaret Ward, Maud Gonne: Ireland's joan of Arc (London: Pandora, I990) X I+ I 2II pp. Margery Brady, The Love Story of Yeats and Maud Gonne (Cork: Mercier Press, I990) I28 pp. Deirdre Toomey Margaret Ward's is the best life of Maud Gonne so far. But that is faint praise. The author has the great advantage of not being at a loss when dealing with Irish politics, and her interest in women in Irish nationalism - see her Unmanageable Revolutionaries: Women and Irish Nationalism (London: Pluto Press, 1984) - results in detailed coverage of Maud Gonne's involvement with women's groups. The biography is very well illustrated and includes a photo graph of the adolescent Iseult which makes the basis of Yeats's infatuation clear. The political and biographical coverage of the earlier part of Maud Gonne's life is not particularly good. Given Margaret Ward's training as a historian, it is regrettable that she presents material from both A Servant of the Queen and Autobiographies without verification. Both are vital but slippery works. Where Yeats's account of his own political career is distorted, self-serving or confused, she follows it without question. I will examine a group of misapprehensions to illustrate the problem. After the debacle of the New Irish Library, Ward states, "Yeats ... did not return to Irish political life tilll897". But Yeats was elected President of the London Young Ireland Society (a front for the Irish National Alliance and Irish Republican Brotherhood) in December 1896: he did not achieve such an important position by staying out of politics.