North Carolina Quakers in the Era of the American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornishness and Englishness: Nested Identities Or Incompatible Ideologies?

CORNISHNESS AND ENGLISHNESS: NESTED IDENTITIES OR INCOMPATIBLE IDEOLOGIES? Bernard Deacon (International Journal of Regional and Local History 5.2 (2009), pp.9-29) In 2007 I suggested in the pages of this journal that the history of English regional identities may prove to be ‘in practice elusive and insubstantial’.1 Not long after those words were written a history of the north east of England was published by its Centre for Regional History. Pursuing the question of whether the north east was a coherent and self-conscious region over the longue durée, the editors found a ‘very fragile history of an incoherent and barely self-conscious region’ with a sense of regional identity that only really appeared in the second half of the twentieth century.2 If the north east, widely regarded as the most coherent English region, lacks a historical identity then it is likely to be even more illusory in other regions. Although rigorously testing the past existence of a regional discourse and finding it wanting, Green and Pollard’s book also reminds us that history is not just about scientific accounts of the past. They recognise that history itself is ‘an important element in the construction of the region … Memory of the past is deployed, selectively and creatively, as one means of imagining it … We choose the history we want, to show the kind of region we want to be’.3 In the north east that choice has seemingly crystallised around a narrative of industrialization focused on the coalfield and the gradual imposition of a Tyneside hegemony over the centuries following 1650. -

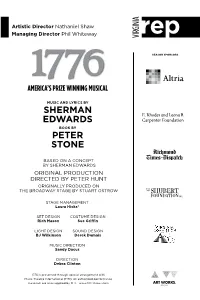

1776, the Musical

For Immediate Release Date: August 31, 2016 Contact: Susan Davenport Director of Communications Virginia Repertory Theatre [email protected] 8047831688 ext 1133 8045138211 Mobile Virginia Repertory Theatre Opens the Signature Season with 1776, the Musical Starring Scott Wichmann as John Adams Richmond, VA Virginia Repertory Theatre announces the opening of 1776, The Musical, at the Sara Belle and Neil November Theatre, 114 West Broad Street on Friday, September 30, 2016 with two previews on September 28 and 29. The show runs through October 23, 2016. Often referred to as “America’s Musical,” 1776 is a lively, funny, and momentous story of the second Continental Congress and the writing of the Declaration of Independence. Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards wrote the musical in the years leading up to America’s bicentennial. It debuted on Broadway in 1969 and won the Tony Award for Best Musical. Virginia Rep will partner with the Virginia Historical Society to provide related talkbacks and discussions throughout the run of the show. Visit http://varep.org/_1776novembertheatrerichmond.html for details. Director Debra Clinton is thrilled to work with such an outstanding cast. “I see 1776 as an opportunity for people to revisit the history of our country and to reflect on what brings us together as Americans. It is a very uplifting story even in the context of hard compromise.” Clinton’s recent credits for Virginia Rep include The Whipping Man and the family smashhit Croaker: The Frog Prince Musical, which she cowrote with Jason Marks. Sandy Dacus will serve as music director. -

Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol

FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 Q Orange County Bound for Congress 2019 Q Spain and the American Revolution Q Battle of Alamance Q James Tilton: 1st U.S. Army Surgeon General Arizona SAR Hosts First Grave Marking FALL 2018 Vol. 113, No. 2 24 Above, the Gen. David Humphreys Chapter of the Connecticut Society participated in the 67th annual Fourth of July Ceremony at Grove Street Cemetery in New Haven, 20 Connecticut; left, the Tilton Mansion, now the University and Whist Club. 8 2019 SAR Congress Convenes 13 Solid Light Reception 20 Delaware’s Dr. James Tilton in Costa Mesa, California The Prison Ship Martyrs Memorial Membership 22 Arizona’a First Grave Marking 14 9 State Society & Chapter News SAR Travels to Scotland 24 10 2018 SAR Annual Conference 16 on the American Revolution 38 In Our Memory/New Members 18 250th Series: The Battle 12 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of Alamance 46 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. -

An Archaeological Inventory of Alamance County, North Carolina

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVENTORY OF ALAMANCE COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA Alamance County Historic Properties Commission August, 2019 AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVENTORY OF ALAMANCE COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA A SPECIAL PROJECT OF THE ALAMANCE COUNTY HISTORIC PROPERTIES COMMISSION August 5, 2019 This inventory is an update of the Alamance County Archaeological Survey Project, published by the Research Laboratories of Anthropology, UNC-Chapel Hill in 1986 (McManus and Long 1986). The survey project collected information on 65 archaeological sites. A total of 177 archaeological sites had been recorded prior to the 1986 project making a total of 242 sites on file at the end of the survey work. Since that time, other archaeological sites have been added to the North Carolina site files at the Office of State Archaeology, Department of Natural and Cultural Resources in Raleigh. The updated inventory presented here includes 410 sites across the county and serves to make the information current. Most of the information in this document is from the original survey and site forms on file at the Office of State Archaeology and may not reflect the current conditions of some of the sites. This updated inventory was undertaken as a Special Project by members of the Alamance County Historic Properties Commission (HPC) and published in-house by the Alamance County Planning Department. The goals of this project are three-fold and include: 1) to make the archaeological and cultural heritage of the county more accessible to its citizens; 2) to serve as a planning tool for the Alamance County Planning Department and provide aid in preservation and conservation efforts by the county planners; and 3) to serve as a research tool for scholars studying the prehistory and history of Alamance County. -

Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers Stephen D. Feeley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Stephen D., "Tuscarora trails: Indian migrations, war, and constructions of colonial frontiers" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4nn0-c987 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tuscarora Trails: Indian Migrations, War, and Constructions of Colonial Frontiers Volume I Stephen Delbert Feeley Norcross, Georgia B.A., Davidson College, 1996 M.A., The College of William and Mary, 2000 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stephen Delbert F eele^ -^ Approved by the Committee, January 2007 MIL James Axtell, Chair Daniel K. Richter McNeil Center for Early American Studies 11 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

An Educator's Guide to the Story of North Carolina

Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide An Educator’s Guide to The Story of North Carolina An exhibition content guide for teachers covering the major themes and subject areas of the museum’s exhibition The Story of North Carolina. Use this guide to help create lesson plans, plan a field trip, and generate pre- and post-visit activities. This guide contains recommended lessons by the UNC Civic Education Consortium (available at http://database.civics.unc.edu/), inquiries aligned to the C3 Framework for Social Studies, and links to related primary sources available in the Library of Congress. Updated Fall 2016 1 Story of North Carolina – Educator’s Guide The earth was formed about 4,500 million years (4.5 billion years) ago. The landmass under North Carolina began to form about 1,700 million years ago, and has been in constant change ever since. Continents broke apart, merged, then drifted apart again. After North Carolina found its present place on the eastern coast of North America, the global climate warmed and cooled many times. The first single-celled life-forms appeared as early as 3,800 million years ago. As life-forms grew more complex, they diversified. Plants and animals became distinct. Gradually life crept out from the oceans and took over the land. The ancestors of humans began to walk upright only a few million years ago, and our species, Homo sapiens, emerged only about 120,000 years ago. The first humans arrived in North Carolina approximately 14,000 years ago—and continued the process of environmental change through hunting, agriculture, and eventually development. -

The Impact of Weather on Armies During the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 The Force of Nature: The Impact of Weather on Armies during the American War of Independence, 1775-1781 Jonathan T. Engel Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE FORCE OF NATURE: THE IMPACT OF WEATHER ON ARMIES DURING THE AMERICAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1775-1781 By JONATHAN T. ENGEL A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2011 The members of the committee approve the thesis of Jonathan T. Engel defended on March 18, 2011. __________________________________ Sally Hadden Professor Directing Thesis __________________________________ Kristine Harper Committee Member __________________________________ James Jones Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii This thesis is dedicated to the glory of God, who made the world and all things in it, and whose word calms storms. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Colonies may fight for political independence, but no human being can be truly independent, and I have benefitted tremendously from the support and aid of many people. My advisor, Professor Sally Hadden, has helped me understand the mysteries of graduate school, guided me through the process of earning an M.A., and offered valuable feedback as I worked on this project. I likewise thank Professors Kristine Harper and James Jones for serving on my committee and sharing their comments and insights. -

God's Faithfulness to Promise

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU ACU Brown Library Monograph Series Volume 1 2019 God’s Faithfulness to Promise: The orH tatory Use of Commissive Language in Hebrews David Ripley Worley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/acu_library_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Worley, David Ripley, "God’s Faithfulness to Promise: The orH tatory Use of Commissive Language in Hebrews" (2019). ACU Brown Library Monograph Series. Vol.1. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/acu_library_books/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ACU Brown Library Monograph Series by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. God’s Faithfulness to Promise The Hortatory Use of Commissive Language in Hebrews David Worley With a Bibliographical Addendum by Lee Zachary Maxey GOD’S FAITHFULNESS TO PROMISE The Hortatory Use of Commissive Language in Hebrews Yale University Ph.D. 1981 GOD’S FAITHFULNESS TO PROMISE The Hortatory Use of Commissive Language in Hebrews A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Yale University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By David Ripley Worley, Jr., May 1981 With a Bibliographical Addendum by Lee Zachary Maxey Copyright © 2019 Abilene Christian University All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-359-30502-5 The open access (OA) ebook edition of this book is licensed under the following Creative Commons license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode ACU Brown Library Monograph Series titles are published by the Scholars Lab at the Abilene Christian University Library Open Access ebook editions of titles in this series are available for free at https://digitalcommons.acu. -

Catawba Militarism: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Overviews

CATAWBA MILITARISM: ETHNOHISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL OVERVIEWS by Charles L. Heath Abstract While many Indian societies in the Carolinas disappeared into the multi-colored fabric of Southern history before the mid-1700s, the Catawba Nation emerged battered, but ethnically viable, from the chaos of their colonial experience. Later, the Nation’s people managed to circumvent Removal in the 1830s and many of their descendants live in the traditional Catawba homeland today. To achieve this distinction, colonial and antebellum period Catawba leaders actively affected the cultural survival of their people by projecting a bellicose attitude and strategically promoting Catawba warriors as highly desired military auxiliaries, or “ethnic soldiers,” of South Carolina’s imperial and state militias after 1670. This paper focuses on Catawba militarism as an adaptive strategy and further elaborates on the effects of this adaptation on Catawba society, particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While largely ethnohistorical in content, potential archaeological aspects of Catawba militarism are explored to suggest avenues for future research. American Indian societies in eastern North America responded to European imperialism in countless ways. Although some societies, such as the Powhatans and the Yamassees (Gleach 1997; Lee 1963), attempted to aggressively resist European hegemony by attacking their oppressors, resistance and adaptation took radically different forms in a colonial world oft referred to as a “tribal zone,” a “shatter zone,” or the “violent edge of empire” (Ethridge 2003; Ferguson and Whitehead 1999a, 1999b). Perhaps unique among their indigenous contemporaries in the Carolinas, the ethnically diverse peoples who came to form the “Catawba Nation” (see Davis and Riggs this volume) proactively sought to ensure their socio- political and cultural survival by strategically positioning themselves on the southern Anglo-American frontier as a militaristic society of “ethnic soldiers” (see Ferguson and Whitehead 1999a, 1999b). -

Professor Stephen Pitti, Yale University Over the Last Century

Professor Stephen Pitti, Yale University Over the last century, scholars have written dozens of important studies that excavate the deep and diverse histories of Latinos in the United States, and that show the central role that Latinos have played in American history for hundreds of years. Community historians, historical preservationists, museum professionals, and non-academic researchers have been equally important to chronicling and preserving those histories. In 2013, when the National Park Service published the American Latinos and the Making of the United States theme study, it recognized that Latino history is a critical and powerful area of scholarship, one that is vital for twenty-first century historical preservation and interpretation. The following bibliography offers only a fraction of the important books that might guide new discussions of the centrality of Latino history to the history of the United States: Acosta-Belén, Edna, and Carlos Enrique Santiago. Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Contemporary Portrait. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2006. Acosta-Belén, Edna. The Puerto Rican Woman: Perspectives on Culture, History, and Society. New York: Praeger, 1986. Acosta, Teresa Palomo. Las Tejanas: 300 Years of History. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003. Adams, John A. Conflict & Commerce on the Rio Grande: Laredo, 1755-1955. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2008. Alamillo, José M. Making Lemonade Out of Lemons: Mexican American Labor and Leisure in a California Town, 1880-1960. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006. Alaniz, Yolanda, and Megan Cornish. Viva La Raza: A History of Chicano Identity and Resistance. Seattle, WA: Red Letter Press, 2008. Alaniz, Yolanda, and Megan Cornish. -

Calendar of North Carolina Papers at London Board of Trade, 1729 - 177

ENGLISH RECORDS -1 CALENDAR OF NORTH CAROLINA PAPERS AT LONDON BOARD OF TRADE, 1729 - 177, Accession Information! Schedule Reference t NON! Arrangement t Chronological Finding Aid prepared bye John R. Woodard Jr. Date t December 12, 1962 This volume was the result of a resolution (N.C. Acts, 1826-27, p.85) pa~sed by the General Assembly of North Carolina, Febuary 9, 1821. This resolution proposed that the Governor of North Carolina apply to the British government for permission to secure copies of documents relating to the Co- lonial history of North Carolina. This application was submitted through the United states Ninister to the Court of St. James, Albert Gallatin. Gallatin vas giTen permission to secure copies of documents relating to the Colonial history of North Carolina. Gallatin found documents in the Board of Trade Office and the "state Paper uffice" (which was the common depository for the archives of the Home, Foreign, and Colonial departments) and made a list of them. Gallatin's list and letters from the Secretary of the Board of Trade and the Foreign Office were sent to Governor H.G. Burton, August 25, 1821 and then vere bound together to form this volume. A lottery to raise funds for the copying of the documents was authorized but failed. The only result 6"emS to have been for the State to have published, An Index to Colonial Docwnents Relative to North Carolina, 1843. [See Thornton, }1ary Lindsay, OffIcial Publications of 'l'heColony and State of North Carolina, 1749-1939. p.260j Indexes to documentS relative to North Carolina during the coloDl81 existence of said state, now on file in the offices of the Board of Trade and state paper offices in London, transmitted in 1827, by Mr. -

Sherman Edwards Peter Stone

Artistic Director Nathaniel Shaw Managing Director Phil Whiteway 1776 SEASON SPONSORS AMERICA’S PRIZE WINNING MUSICAL MUSIC AND LYRICS BY SHERMAN E. Rhodes and Leona B. EDWARDS Carpenter Foundation BOOK BY PETER STONE BASED ON A CONCEPT BY SHERMAN EDWARDS ORIGINAL PRODUCTION DIRECTED BY PETER HUNT ORIGINALLY PRODUCED ON THE BROADWAY STAGE BY STUART OSTROW STAGE MANAGEMENT Laura Hicks* SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN Rich Mason Sue Griffin LIGHT DESIGN SOUND DESIGN BJ Wilkinson Derek Dumais MUSIC DIRECTION Sandy Dacus DIRECTION Debra Clinton 1776 is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com CAST MUSICAL NUMBERS AND SCENES ACT I MEMBERS OF THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS For God’s Sake, John, Sit Down ............................... Adams & The Congress Piddle, Twiddle ............................................................. Adams President Delaware Till Then .......................................................... Adams & Abigail John Hancock............ Michael Hawke Caesar Rodney ........... Neil Sonenklar The Lees of Old Virginia ......................................Lee, Franklin & Adams Thomas McKean ..... Andrew C. Boothby New Hampshire But, Mr. Adams — .................. Adams, Franklin, Jefferson, Sherman & Livingston George Read ................ John Winn Dr. Josiah Bartlett ......Joseph Bromfield Yours, Yours, Yours ................................................ Adams & Abigail Maryland He Plays the Violin ........................................Martha,