Travels Without

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide Touristique 2020-2021

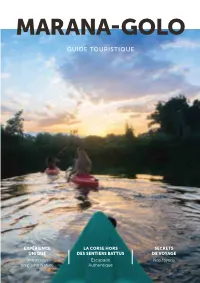

MARANA-GOLO GUIDE TOURISTIQUE EXPÉRIENCE LA CORSE HORS SECRETS UNIQUE DES SENTIERS BATTUS DE VOYAGE Immersion Escapade Nos favoris en pleine Nature Authentique Parc de Saleccia 03 LES BONNES RAISONS DE VENIR À MARANA-GOLO ! 08 | LA MER 12 | LA NATURE 20 | LA FAMILLE 26 | PARTIR À LA DÉCOUVERTE 50 | NOS TABLES 56 | PRODUCTEURS & ARTISANS 60 | OÙ DORMIR 74 | SE DÉPLACER UN LIEU UNIQUE 05 BIENVENUE À MARANA-GOLO ! Venez passer vos vacances en Corse dans une région unique ! Entité géographique de la plaine orientale de Corse, Marana Golo, ouverte sur la mer Tyrrhénienne, présente les atouts de territoires variés. Face à l’archipel Toscan, de l’embouchure du fleuve du Golo aux portes de la Ville de Bastia, Le Lido de la Marana confine la Réserve Naturelle de l’Étang de Biguglia et intègre un ensemble de microrégions. Entre mer et montagne, Marana-Golo alterne paysages d’exception, sites historiques et villages de caractère aux charmes authentiques, nichés au cœur du piémont, où règnent les senteurs du maquis fait d’arbousiers et de bruyères… Venez vivre une escapade inoubliable… Marana Golo vous attend ! DIRECTION D82 Saint-Florent LÉGENDE 01 La mer . p.09 11 La nature . p.13 D82 14 En famille . p.21 BAIGNADES EN RIVIÈRE D82 26 Accès par Sole e Frescu 30 42.52559, 9.41109 27 Accès par Barchetta 42.50655, 9.37433 28 Accès par le Torrent de Cipetto 42.51023, 9.33905 29 Accès par Accendi pipa 42.50634, 9.31898 30 Accès par le Jardin d’Antoine 42.5933, 9.36345 D5 Bigorno Campitello Scolca Lento D7 D15 28 T20 D5 29 27 DIRECTIONS Corte Île-Rousse -

Alluvial Geochronology and Watershed Analysis of the Golo River, Northeastern Corsica, France

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 12-2013 Alluvial Geochronology and Watershed Analysis of the Golo River, Northeastern Corsica, France Emilee M. Skyles Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Skyles, Emilee M., "Alluvial Geochronology and Watershed Analysis of the Golo River, Northeastern Corsica, France" (2013). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 2045. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/2045 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALLUVIAL GEOCHRONOLOGY AND WATERSHED ANALYSIS OF THE GOLO RIVER, NORTHEASTERN CORSICA, FRANCE by Emilee M. Skyles A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Geology Approved: _________________________ _________________________ Dr. Tammy Rittenour Dr. Joel Pederson Major Professor Committee Member _________________________ _________________________ Dr. Patrick Belmont Mark R. McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2013 ii Copyright © Emilee M. Skyles 2013 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Alluvial Geochronology and Watershed Analysis of the Golo River, Northeastern Corsica, France by Emilee M. Skyles, Master of Science Utah State University, 2013 Major Professor: Dr. Tammy M. Rittenour Department: Geology The Golo River in northeastern Corsica, France, is a short, steep, mixed bedrock-alluvial river (~95 km, 2706 m relief) in the Western Mediterranean with formerly glaciated headwaters. -

Mise En Page

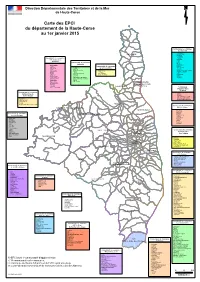

Direction Départementale des Territoires et de la Mer de Haute-Corse Carte des EPCI du département de la Haute-Corse au 1er janvier 2015 Communauté de communes du Cap Corse CAP-CORSE BARRETTALI BRANDO CAGNANO Communauté de communes CANARI di E cinque pieve CENTURI di Balagna ERSA Communauté de communes LURI du Nebbiu MERIA BELGODERE MORSIGLIA COSTA Communauté de communes NONZA FELICETO MURATO de la Conca d'Oru OGLIASTRO LAMA OLETTA OLCANI MAUSOLEO OLMETA DI TUDA BARBAGGIO OLMETA DI CAPO CORSO MURO PIEVE FARINOLE PIETRACORBARA NESSA POGGIO D'OLETTA PATRIMONIO PINO NOVELLA RAPALE SAINT-FLORENT ROGLIANO OCCHIATANA RUTALI SISCO OLMI-CAPELLA SAN GAVINO DI TENDA TOMINO PALASCA SANTO PIETRO DI TENDA PIETRALBA SORIO PIOGGIOLA VALLECALLE COMMUNAUTE SPELONCATO URTACA D'AGGLOMERATION VALLICA CONCA-D'ORO DE BASTIA VILLE DI PARASO Communauté d'Agglomération de Bastia Communauté de communes du Bassin de vie BASTIA de l'Ile Rousse FURIANI SAN MARTINO DI LOTA SANTA MARIA DI LOTA CORBARA VILLE DI PIETRABUGNO L'ILE ROUSSE MONTICELLO PIGNA SANTA REPARATA DI BALAGNA NEBBIU Communauté de communes BASSIN DE VIE DE L'ILE ROUSSE Marana et Golo MARANA GOLO BIGORNO BIGUGLIA Communauté de communes CINQUE PIEVE DI BALAGNA BORGO de Calvi Balagne CAMPITELLO LENTO LUCCIANA ALGAJOLA MONTE AREGNO OLMO AVAPESSA SCOLCA CALENZANA VIGNALE CALVI CATERI CASINCA GALERIA LAVATOGGIO LUMIO CASACCONI Communauté de communes MANSO VALLEE DU GOLO MONCALE E GOLU du Casacconi e MONTEGROSSO SUTTANU Golu Suttanu SANT'ANTONINO ZILIA CALVI-BALAGNE BISINCHI CAMPILE OREZZA CROCICCHIA ORTIPORIO -

Acari, Hydrachnidia: Hygrobatidae) in Corsica and Sardinia

The water mites of the genus Atractides Koch, 1837 (Acari, Hydrachnidia: Hygrobatidae) in Corsica and Sardinia Reinhard GERECKE Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Département Systématique et Évolution, CNRS UMR-7205, case postale 53, 57 rue Cuvier, F-75231 Paris cedex 05 (France) and Biesingerstr. 11, 72070 Tübingen (Germany) [email protected] Gerecke R. 2014. — The water mites of the genus Atractides Koch, 1837 (Acari, Hydrachnidia: Hygrobatidae) in Corsica and Sardinia. Zoosystema 36 (4): 735-759. http://dx.doi.org/10.5252/ z2014n4a3 ABSTRACT Based on bibliographic data, material from coll. E. Angelier and own field work of the author done in the late 20th century, a survey is given on the diversity and distribution of spring- and stream-dwelling water mites of the genus Atractides Koch, 1837 on Corsica and Sardinia. Published information on presence of Atractides in the area covered was restricted to Corsica (Angelier 1954a, b; Santucci 1965, 1971, 1977; Giudicelli 1970; Gerecke & Di Sabatino 2013). Redescriptions are given of the incompletely documented species Atractides gracilipes (E. Angelier, 1951) (no more documented by type material) and A. corsicus E. Angelier, 1954 (of which six syntypes could be detected in NHMB). Published records (in brackets) are referred to the species A. robustus (Sokolow, 1940) and A. acutirostris Motaş & Angelier, 1928. In total, 24 Atractides species are now known from the two islands, 50 % of them recorded here for the first time: Atractides allgaier Gerecke, 2003, A. clavipes Lundblad, 1954, A. fonticolus (K. Viets, 1950), A. graecus K. Viets, 1950, A. inflatus (Walter, 1925), A. loricatus Piersing, 1898, A. -

Decoupage Ok2014cantons Commune.Mxd

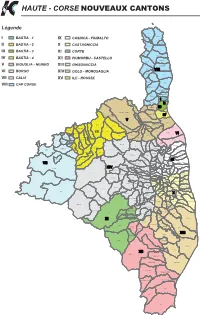

HAUTE - CORSE NOUVEAUX CANTONS Légende ERSA I IX ROGLIANO BASTIA - 1 CASINCA - FIUMALTO CENTURI II X TOMINO BASTIA - 2 CASTAGNICCIA MORSIGLIA MERIA III BASTIA - 3 XI CORTE PINO LURI IV BASTIA - 4 XII FIUMORBU - CASTELLO CAGNANO BARRETTALI V XIII BIGUGLIA - NEBBIO GHISONACCIA PIETRACORBARA CANARI VIIIVIII VI BORGO XIV GOLO - MOROSAGLIA OGLIASTRO SISCO VII CALVI XV ILE - ROUSSE OLCANI NONZA BRANDO VIII CAP CORSE OLMETA-DI-CAPOCORSO SANTA-MARIA-DI-LOTA SAN-MARTINO-DI-LOTA FARINOLE I BASTIA 1 PATRIMONIO IIII BASTIA 2 BARBAGGIO IIIIII BASTIA 3 SAINT-FLORENT SANTO-PIETRO-DI-TENDA POGGIO-D'OLETTA BASTIA 4 RAPALE IVIV SAN-GAVINO-DI-TENDA V OLETTA BIGUGLIA PALASCA OLMETA-DI-TUDA L'ILE-ROUSSE URTACA MONTICELLO VALLECALLE CORBARA BELGODERE XV NOVELLA RUTALI BORGO SANTA-REPARATA-DI-BALAGNA VIVI ALGAJOLA PIGNA SORIO LAMA MURATO AREGNO VILLE-DI-PARASO SANT'ANTONINO PIEVE COSTA OCCHIATANA SPELONCATO LUCCIANA LUMIO LAVATOGGIO CATERI SCOLCA VIGNALE AVAPESSA PIETRALBA BIGORNO VESCOVATO MURO NESSA LENTO CAMPITELLO FELICETO OLMI-CAPPELLA VOLPAJOLA MONTEGROSSO CASTIFAO PRUNELLI-DI-CASACCONI CALVI VENZOLASCA OLMO PIOGGIOLA VALLICA CAMPILE SORBO-OCAGNANO ZILIA CANAVAGGIA BISINCHI MONTE LORETO-DI-CASINCA CASTELLARE-DI-CASINCA MONCALE MAUSOLEO CROCICCHIA CASTELLO-DI-ROSTINO IXIX PENTA-ACQUATELLA MOLTIFAO PENTA-DI-CASINCA SILVARECCIO VIIVII VALLE-DI-ROSTINO ORTIPORIO PORRI CASABIANCA PIANO GIOCATOJO TAGLIO-ISOLACCIO MOROSAGLIA CASALTA XIVXIV PIEDIGRIGGIO CALENZANA POGGIO-MARINACCIO PRUNO TALASANI POPOLASCA QUERCITELLO SCATA CASTINETA FICAJA SAN-GAVINO-D'AMPUGNANIPERO-CASEVECCHIE -

The Pianosa Contourite Depositional System (Northern Tyrrhenian Sea): Drift Morphology and Plio-Quaternary Stratigraphic Evolution

1 Marine Geology Achimer August 2016, Volume 378, Pages 20-42 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.margeo.2015.11.004 http://archimer.ifremer.fr http://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00292/40330/ © 2015 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved The pianosa contourite depositional system (northern Tyrrhenian sea): drift morphology and plio-quaternary stratigraphic evolution Miramontes Garcia Elda 1, *, Cattaneo Antonio 1, Jouet Gwenael 1, Théreau Estelle 1, Thomas Yannick 1, Rovere Mickael 2, Cauquil E. 3, Trincardi F. 2 1 IFREMER, Géosciences Marines-EDROME, Centre de Brest, BP70, CS10070, 29280 Plouzané, France 2 ISMAR-CNR, Via P. Gobetti 101, 40129, Bologna, Italy 3 TOTAL SA, La Défense, France * Corresponding author : Elda Miramontes Garcia, email address : [email protected] Abstract : The Pianosa Contourite Depositional System (CDS) is located in the Corsica Trough (Northern Tyrrhenian Sea), a confined basin dominated by mass transport and contour currents in the eastern flank and by turbidity currents in the western flank. The morphologic and stratigraphic characterisation of the Pianosa CDS is based on multibeam bathymetry, seismic reflection data (multi-channel high resolution mini GI gun, single-channel sparker and CHIRP), sediment cores and ADCP data. The Pianosa CDS is located at shallow to intermediate water depths (170 to 850 m water depth) and is formed under the influence of the Levantine Intermediate Water (LIW). It is 120 km long, has a maximum width of 10 km and is composed of different types of muddy sediment drifts: plastered drift, separated mounded drift, sigmoid drift and multicrested drift. The reduced tectonic activity in the Corsica Trough since the early Pliocene permits to recover a sedimentary record of the contourite depositional system that is only influenced by climate fluctuations. -

Communauté De Communes Marana - Golo

COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES MARANA - GOLO DONNÉES DE CADRAGE La communauté de communes Marana - Golo regroupe 10 communes : Bigorno, Biguglia, Borgo, Campitello, Lento, Lucciana, Monte, Olmo, Scolta et Vignale Superficie : 166,98 km² 13,3 % des habitants de l’ancien département de la Haute-Corse résident dans la communauté de communes, à l’échelle de la région la part s’élève à 7,1 % [email protected] / 04 95 50 91 32 CORSICA STATISTICA - ADEC - Maison du Parc Technologique - 20 600 Bastia STRUCTURE DE LA POPULATION Effectifs Taux SOURCE : INSEE, RP 2015 - TRAITEMENT CORSISTAT Population de femmes 11 512 49,7 Nombre d’habitants : 23 186 soit 139 habitants au km² Population d’hommes 11 674 50,3 Nombre de naissances domiciliés en 2017 250 Dont : Nombre de familles avec enfants 3 109 32,8 • 36,7 % à Borgo Dont nombre de familles monoparentales 1 060 11,2 • 34,3 % à Biguglia • 23,2 % à Lucciana Population étrangère 2 226 9,6 Indice de vieillissement : 59,0 contre 107,7 en région Définition : nombre de personne âgées de 65 ans et plus pour 100 personnes âgées de moins de 20 ans Évolution démographique - base 100 au RP 1975 Répartition de la population par tranches d’âges SOURCE : INSEE, RP 1975 À 2015 - TRAITEMENT CORSISTAT SOURCE : INSEE, RP 2015 - TRAITEMENT CORSISTAT 300 280 75 ans ou plus 1413 260 240 60 à 74 ans 3286 220 200 45 à 59 ans 4893 180 30 à 44 ans 5252 160 140 15 à 29 ans 4079 120 100 0 à 14 ans 4263 1975 1982 1990 1999 2010 2015 CC Marana Golo Corse LOGEMENTS SOURCE : INSEE, RP 2015 - TRAITEMENT CORSISTAT Nombre de -

Invasions of the Non-Indigenous Red Alga Lophocladia Lallemandii (Montagne) F

BioInvasions Records (2021) Volume 10, Issue 1: 91–102 CORRECTED PROOF Rapid Communication Invasions of the non-indigenous red alga Lophocladia lallemandii (Montagne) F. Schmitz off the Island of Ischia (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy) Luca Tiberti1, Gianluca Iacono1, Maria Cristina Gambi2,1 and Anna Maria Mannino3,* 1Nemo, Associazione per la Diffusione della Cultura del Mare, Serrara Fontana, Island of Ischia, Napoli, Italy 2Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Napoli; Department of Integrative Marine Ecology, Ischia Marine Center, Island of Ischia, Napoli, Italy 3Department of Biological, Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences and Technologies, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy Author e-mails: [email protected] (LT), [email protected] (GI), [email protected] (MCG), [email protected] (AMM) *Corresponding author Luca Tiberti and Gianluca Iacono contributed equally to this work. Citation: Tiberti L, Iacono G, Gambi MC, Mannino AM (2021) Invasions of the non- Abstract indigenous red alga Lophocladia lallemandii (Montagne) F. Schmitz off the Island of This paper describes the distribution and spread of the non-indigenous red alga Ischia (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). Lophocladia lallemandii (Montagne) F. Schmitz along the coast of the Island of BioInvasions Records 10(1): 91–102, Ischia (Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). Lophocladia lallemandii was monitored through https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2021.10.1.11 surveys from July 2019 to January 2020 at the Capo Sant’Angelo (Ischia), where Received: 16 April 2020 L. lallemandii was observed, but not reported, in the years preceding the invasion Accepted: 21 July 2020 of the upper rocky infralittoral shore reported here. It is noteworthy that a large Published: 9 December 2020 portion of the study area is included within one of the two “B no-take” zones of the Marine Protected Area of the “Regno di Nettuno” (“Neptune’s Realm”). -

L'entomologiste Tome 64 (2008), Numéro 3

Contribution à la connaissance des Neuropterida de Corse (Raphidioptera et Neuroptera). Micromus angulatus (Stephens, 1836), Microminae nouveau pour la faune de Corse (Neuroptera Hemerobiidae) Matthieu Giacomino 9 rue du Limousin, F-53940 Saint-Berthevin [email protected] Résumé. – De nouvelles données de Neuropterida capturés en Corse sont exposées, complétant la liste de Letardi et al. [2008], déjà enrichie par la découverte de Tillier [2010]. La présence de Micromus angulatus (Stephens, 1836) est désormais avérée. La larve de Nevrorthus fallax (Rambur, 1842), au dernier stade, est figurée (photos), des précisions phylogéniques sur les Nevrorthidae (Neuroptera Nevrorthiformia), issues de la littérature, sont rapportées. Summary. – Contribution to the knowledge of Neuropterida of Corsica (Raphidioptera and Neuroptera). Micromus angulatus (Stephens, 1836), new Microminae for the fauna of Corsica (Neuroptera Hemerobiidae). Some new data of Neuropterida captured in Corsica are given, updating the Letardi et al. [2008] list, also completed by Tillier [2010]. The actual occurrence of Micromus angulatus (Stephens, 1836) is established for the Corsican fauna. Some pictures of Nevrorthus fallax (Rambur, 1842), at the final larval state, are given, as well as some phylogenic precisions (coming from literature). Keywords. – Neuropterida, New data, Micromus angulatus, Larva of Nevrorthus fallax, Corsican fauna. Récemment, la mise à jour de la faune des des abords de cours d’eau. La totalité des Neuropterida (Névroptères sensu lato) de imagos ont été recueillis au parapluie japonais Corse faite par Letardi et al. [2008], enrichie ou au filet à papillons ; les larves aquatiques de de la découverte de Neuroleon microstenus Nevrorthus fallax l’ont été grâce à une passoire à (McLachlan, 1898) par Tillier [2010], a riz (maille fine). -

GPR Survey at the Roman Town of Mariana \(Corsica\)

ArcheoSciences Revue d'archéométrie 33 (suppl.) | 2009 Mémoire du sol, espace des hommes GPR survey at the Roman town of Mariana (Corsica) Lieven Verdonck and Frank Vermeulen Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/1635 DOI: 10.4000/archeosciences.1635 ISBN: 978-2-7535-1599-4 ISSN: 2104-3728 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Printed version Date of publication: 30 October 2009 Number of pages: 241-243 ISBN: 978-2-7535-0943-6 ISSN: 1960-1360 Electronic reference Lieven Verdonck and Frank Vermeulen, “GPR survey at the Roman town of Mariana (Corsica)”, ArcheoSciences [Online], 33 (suppl.) | 2009, Online since 30 October 2011, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/archeosciences/1635 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ archeosciences.1635 Article L.111-1 du Code de la propriété intellectuelle. GPR survey at the Roman town of Mariana (Corsica) Lieven Verdonck* and Frank Vermeulen* Key words: Ground-penetrating radar, archaeological interpretation, three-dimensional visualisation, Roman archaeology, Corsica (France) In the last ten years, ground-penetrating radar (GPR) has ns) for the very dry topsoil in the month of September, become one of the most valuable methods for the non-inva- decreasing to around 0.075 m/ns at a depth of 1.5 m. sive investigation of complex urban sites (see e.g. Neubauer Since the complex results could not easily be interpre- et al., 2002; Gaff ney et al., 2004; Seren et al., 2004; ted on the basis of profi les or depth-slices alone, a three- Leckebusch & Sütterlin, 2007). Th is contribution summa- dimensional interpretation was made (Fig. -

Clinocerinae \(Diptera : Empididae\) from Corsica with the Description Of

Annls Limnol 32 (3) 1996 : 171-184 Clinocerinae (Díptera : Empididae) from Corsica with the description of six new species M.H.E. Pusch1 Keywords : Empididae, Clinocerinae, new species, Corsica. During the summers 1992 and 1993, 15 species of Clinocerinae (Empididae) were collected on Corsica. The illustrated des criptions of six new species are given: Roederiodes wagneri sp. n., Clinocera (Kowarzia) cataractae sp. n., Wiedemannia (Chcunaedipsia) ariolae sp. n., Wiedemannia (Chamaedipsia) bravonae sp. n., Wiedemannia (Philolutra) kallistes sp. n. and Wiedemannia (Wiedemannia) martini sp. n.. Their systematic relations with other species are discussed. Informations is given about their geographic distribution and their habitats. Les Clinocerinae (Díptera : Empididae) de Corse avec la description de six espèces nouvelles Mots clés : Empididae, Clinocerinae, nouvelles espèces, Corse. Pendant les étés 1992 et 1993, 15 espèces de Clinocerinae (Empididae) ont été récoltées entorse. Les six espèces nouvelles sont décrites : Roederiodes wagneri sp. n., Clinocera (Kowarzia) cataractae sp. n., Wiedemannia (Chamaedipsia) ariolae sp. n., Wiedemannia (Chamaedipsia) bravonae sp. n., Wiedemannia (Philolutra) kallistes sp. n. et Wiedemannia (Wiedemannia) marti ni sp. n.. Les relations systématiques avec d'autres espèces sont discutées. Des informations sur la distribution géographique et les habitats sont données. 1. Introduction streams, or hanging obliquely over them, and in hygro- The island of Corsica is one of the most important petric zones. centres of endemism for freshwater invertebrates in The Clinocerinae of Corsica have been studied scar Europe. In that respect it can be compared with the cely up to now. Since the collection tour of Becker et Iberian peninsula and the Caucasus mountains (lilies al. -

M E R M É D I T E Rranée AJACCIO BASTIA

Sisco Abro Ogliastro Marine de Sisco Olcani Marine d'Albo Nonza D80 D Erbalunga 8 0 Brando e Olmeta- é Golfe di-Capocorso n Santa-Maria-di-Lota Miomo a de r St-Florent San-Martino-di-Lota r Ville-di-Pietrabugno e D31 t Patrimonio BASTIA nte i Ze Barbaggio D81 a t e s 479 g r i St-Florent D81 d s A Cima d'Ifana d e t Casta D38 e r Furiani é é s D82 D D81 la Marana D81 Poggio-d'Oletta M Baccialu Coincet Etang Monetta Biguglia de Ile de la Pietra Lozari Oletta Casatorra Biguglia N197 l'Ile-Rousse N197 Pineto r Guardiola O Santo-Pietro- Olmeta-di-Tuda N193 s D62 D107 tri di-Tenda D62 Monticello co Corbara ni Corbara N197 D82 Ortale e Urtaca Rapale D5 Algajola Santa-Reparata- San-Gavino- Bastia- Pigna di-Balagna di-Tenda M 1 1535 Piève Rutali Poretta 5 Palasca Sorio Plage-de-la-Marana 1 Lama Murato Borgo D Belgodère Novella Monte Asto o Sant'Antonino inc 7 ev Cima di Crucetta 10 Plage-de-Pineto Aregno 1 B D Punta de la Revellata Lumio D7 Costa Tanoria Vignale Calvi Vignale Lucciana Lavatoggio N197 Pietralba 1224 o Speloncato ol Avapessa Pedano Bigorno Campitello Funtanone G N Casamozza Cap Sud N197 av Pioggiola ac Lento Volpajola Muro ci N197 Prunelli- Feliceto Olmi-Cappella Piana a Pietra-Major Vallica N193 di-Casacconi Montegrosso Zilia Canavaggia Barchetta D151 Mausoléo Campile Olmo Vescovato Querciolo ine Castifao Calvi- rtag Ponte Novu N198 Anghione Moncale Ta Sorbo- Ste-Catherine Moltifao olo Calenzana Punta G Crocicchia Ocagnano Castellare- D Tarazone Radiche Mulivecchi 8 Suare San-Pellegrino 1 2393 D47 di-Casinca B Valle- Castello-