The Frame: Architecture and Design of Exhibitions of Islamic Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Le Musée Aga Khan Célèbre La Créativité Et Les Contributions Artistiques Des Immigrants Au Cours D’Une Saison Qui Fait La Part Belle À L’Immigration

Le Musée Aga Khan célèbre la créativité et les contributions artistiques des immigrants au cours d’une saison qui fait la part belle à l’immigration Cinquante-et-un artistes plasticiens, 15 spectacles et 10 orateurs représentant plus de 50 pays seront à l’honneur lors de cette saison dédiée à l’immigration. Toronto, Canada, le 4 mars 2020 - Loin des gros-titres sur l’augmentation de la migration dans le monde, le Musée Aga Khan célèbrera les contributions artistiques des immigrants et des réfugiés à l’occasion de sa nouvelle saison. Cette saison dédiée à l’immigration proposera trois expositions mettant en lumière la créativité des migrants et les contributions artistiques qu’ils apportent tout autour du monde. Aux côtés d’artistes et de leaders d’opinion venant du monde entier, ces expositions d’avant-garde présenteront des individus remarquables qui utilisent l’art et la culture pour surmonter l’adversité, construire leurs vies et enrichir leurs communautés malgré les déplacements de masse, le changement climatique et les bouleversements économiques. « À l’heure où la migration dans le monde est plus importante que jamais, nous, au Musée Aga Khan, pensons qu’il est de notre devoir de réfuter ces rumeurs qui dépeignent les immigrants et les réfugiés comme une menace pour l’intégrité de nos communautés », a déclaré Henry S. Kim, administrateur du Musée Aga Khan. « En tant que Canadiens, nous bénéficions énormément de l’arrivée d’immigrants et des nouveaux regards qu’ils apportent. En saisissant les occasions qui se présentent à eux au mépris de l’adversité, ils incarnent ce qu’il y a de mieux dans l’esprit humain. -

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner Islamic Geometric Patterns Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction with a chapter on the use of computer algorithms to generate Islamic geometric patterns by Craig Kaplan Jay Bonner Bonner Design Consultancy Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA With contributions by Craig Kaplan University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada ISBN 978-1-4419-0216-0 ISBN 978-1-4419-0217-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-0217-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017936979 # Jay Bonner 2017 Chapter 4 is published with kind permission of # Craig Kaplan 2017. All Rights Reserved. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

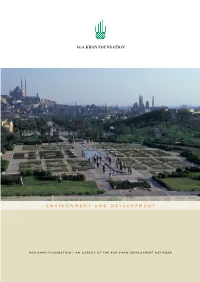

Environment and Development AGA KHAN FOUNDATION

AGA KHAN FOUNDATION E N V I R ON ME NT A ND D EVEL O PME NT AG A K H A N F O U N D AT I O N – A N A G E N C Y O F TH E A G A K H A N D EVEL O PME NT N E T W O RK 1 COver: AL-AZHar Park, CAIRO, EGypT THE CREATION OF A PARK FOR THE CITIZENS OF THE EGYPTIAN CAPITAL, ON A 30-HECTARE (74-ACRE) MOUND OF RUBBLE ADJACENT TO THE HISTORIC CITY, HAS EVOLVED WELL BEYOND THE GREEN SPACE OF THE PARK TO INCLUDE A VARIETY OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC INITIATIVES IN THE NEIGHBOURING DARB AL-AHMAR DISTRICT. THE PARK ITSELF ATTRACTS AN AVERAGE OF 3,000 PEOPLE A DAY AND AS MANY AS 10,000 DAILY DURING RAMADAN. 2 CONTENTS 2 Foreword 3 About the Aga Khan Foundation 5 The Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan Fund for the Environment Case Studies: 9 • A “Green Lung” for Cairo 10 • Environmental Water and Sanitation 11 • Reforestation and Land Reclamation 12 • Environmentally Friendly Tourism Infrastructure 14 • Water Conservation 16 • Sustainable Energy for Developing Economies 18 • Fuel-Saving Stoves and Healthier Houses 19 • A University for Development in Mountain Environments 20 Environmental Awards for AKDN Programmes 24 About Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan and His Highness the Aga Khan 24 About the Aga Khan Development Network 26 AKDN Partners in Environment and Development 1 FOREWORD RiGHT: QESHLAQ-I-BAIKH VILLAGE, AFGHANISTAN IN recent Years, A DROught has COmpOunded difficulties EXperienced due TO the large-scale destructiON OF the agricultural infrastruc- ture and the sudden influX OF Afghan returnees frOM ABROad. -

THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY in CAIRO School of Humanities And

1 THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY IN CAIRO School of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of Arab and Islamic Civilizations Islamic Art and Architecture A thesis on the subject of Revival of Mamluk Architecture in the 19th & 20th centuries by Laila Kamal Marei under the supervision of Dr. Bernard O’Kane 2 Dedications and Acknowledgments I would like to dedicate this thesis for my late father; I hope I am making you proud. I am sure you would have enjoyed this field of study as much as I do. I would also like to dedicate this for my mother, whose endless support allowed me to pursue a field of study that I love. Thank you for listening to my complains and proofreads from day one. Thank you for your patience, understanding and endless love. I am forever, indebted to you. I would like to thank my family and friends whose interest in the field and questions pushed me to find out more. Aziz, my brother, thank you for your questions and criticism, they only pushed me to be better at something I love to do. Zeina, we will explore this world of architecture together some day, thank you for listening and asking questions that only pushed me forward I love you. Alya’a and the Friday morning tours, best mornings of my adult life. Iman, thank you for listening to me ranting and complaining when I thought I’d never finish, thank you for pushing me. Salma, with me every step of the way, thank you for encouraging me always. Adham abu-elenin, thank you for your time and photography. -

Interim Dividend

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e‐form IEPF‐2 CIN/BCIN L34101PN1961PLC015735 Prefill Company/Bank GABRIEL INDIA LIMITED Date of AGM 13‐AUG‐2019 FY‐1 FY‐2 FY‐3 FY‐4 FY‐5 FY‐6 FY‐7 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 984364.70 Number of underlying Shares 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of matured deposits 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposits 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Sum of Other Investment Types 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Validate Clear Is the shares Is the transfer from Proposed Date of Investment Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id‐Client Id‐ Amount Joint Holder unpaid Investor First Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF PAN Date of Birth Aadhar Number Nominee Name Remarks (amount / Financial Year Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred Name suspense (DD‐MON‐YYYY) shares )under account any litigation. -

United Nations Archives

- \ • <\ � Cj \Cl OL � I \.L �- � � l Date arrived date departed Purp:>se I Freetown 5 June 6 June Official visit witH Mrs. Perez de CUellar. Weds. 5 une: ar i ed by private plane frcm Al::uja, Ni ria. t at airp:>rt by Vice- depart by helicopter for guest President lial � c;;;Qerif and.FM �1 /** house. Kar .i.m Korcma. 1 �Hdga �g8gpfiORSffi9iOR&r of SG by Vice es. Cherif (with Mrs. Perez de CUellar) , fo �owed by dinner by Mr. Onder Yucer (UNDP -Res. Coordinator) in honour of SG and Mrs. Pere-z de CUellar, and attended by reps. of UN System and Specialized - • 6 Formal welco,ing ceranony at State House, Agencies Thurs. June : * *� with Pres • folloY.ed by rreeting with: Jos� � f:iaroh (S� � .. .. s t� �); encies ; f ; Wn� � HADPRESS ENCOUNTER; � �· L� Conakry, Guinea. Conakry 6 June 1991 8 June 1991 Official visit with Mrs. Perez de CUellar. Thurs. 6 June: arrived frcm Freetown by private plane. Met at ai rt by . President Conte (GUJNEA) , ilas�®i1�d ** andmet �iefly with of Honour. *!NStaxiak�n . press. met/w1 ��es. Conte; and FM �. Private d· er. Fri. 7 June ..... _ ...... Had rreeting with H.E, • Sylla (Min. for LiEut. "·-.p..J_�ing and Cooperll'tion) and H. E. Mx¥. 6fiji� Col. traore (Fr.'i)-1- met with reps. of UN Specialzied agenci es; priv:�te luncheon;. Boat trip to !les de Loos (wi��s. Perez de CUellar); Briefing by �-�ekio (�R· �-n.,ur;mP) on Technical. �ting �t...._ UN and/tfffli8f"als.� Attended 5)tld made toast""-at- banquet in his honour bf FM 'Fraore (with Mrs. -

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum: a Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers, Grades One to Eight

Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight INTRODUCTION TO THE AGA KHAN MUSEUM The Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, Canada is North America’s first museum dedicated to the arts of Muslim civilizations. The Museum aims to connect cultures through art, fostering a greater understanding of how Muslim civilizations have contributed to world heritage. Opened in September 2014, the Aga Khan Museum was established and developed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC), an agency of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). Its state-of-the-art building, designed by Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki, includes two floors of exhibition space, a 340-seat auditorium, classrooms, and public areas that accommodate programming for all ages and interests. The Aga Khan Museum’s Permanent Collection spans the 8th century to the present day and features rare manuscript paintings, individual folios of calligraphy, metalwork, scientific and musical instruments, luxury objects, and architectural pieces. The Museum also publishes a wide range of scholarly and educational resources; hosts lectures, symposia, and conferences; and showcases a rich program of performing arts. Learning at the Aga Khan Museum A Curriculum Resource Guide for Teachers Grades One to Eight Patricia Bentley and Ruba Kana’an Written by Patricia Bentley, Education Manager, Aga Khan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be Museum, and Ruba Kana’an, Head of Education and Scholarly reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any Programs, Aga Khan Museum, with contributions by: form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publishers. -

![Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5083/diamond-jubilee-his-highness-the-aga-khan-iv-1957-2017-145083.webp)

Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]

DIAMOND JUBILEE HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN IV [1957 – 2017] . The Diamond Jubilee What is the Diamond Jubilee? The Diamond Jubilee marks the 60th anniversary of His Highness the Aga Khan’s leadership as the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslim Community. On 11th July, 1957, the Aga Khan, at the age of 20, assumed the hereditary office of Imam established by Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family), following the passing of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan. Why is the Community celebrating His Highness the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee? The commemoration of the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee is in keeping with the Ismaili Community’s longstanding tradition of marking historic milestones. Over the past six decades, the Aga Khan has transformed the quality of life of hundreds of millions of people around the world. In the areas of health, education, cultural revitalisation, and economic empowerment, he has inspired excellence and worked to improve living conditions and opportunities in some of the world’s most remote and troubled regions. The Diamond Jubilee is an opportunity for the Shia Ismaili Muslim community, partners of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), and government and faith community leaders in over 25 countries to express their appreciation for His Highness’s leadership and commitment to improve the quality of life of the world’s most vulnerable populations. It is also an occasion for His Highness to recognise the friendship and longstanding support of leaders of governments and partners in the work of the Imamat and to set the direction for the future. -

Soviet Central Asia and the Preservation of History

humanities Article Soviet Central Asia and the Preservation of History Craig Benjamin Frederik J Meijer Honors College, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; [email protected] Received: 23 May 2018; Accepted: 9 July 2018; Published: 20 July 2018 Abstract: Central Asia has one of the deepest and richest histories of any region on the planet. First settled some 6500 years ago by oasis-based farming communities, the deserts, steppe and mountains of Central Asia were subsequently home to many pastoral nomadic confederations, and also to large scale complex societies such as the Oxus Civilization and the Parthian and Kushan Empires. Central Asia also functioned as the major hub for trans-Eurasian trade and exchange networks during three distinct Silk Roads eras. Throughout much of the second millennium of the Common Era, then under the control of a succession of Turkic and Persian Islamic dynasties, already impressive trading cities such as Bukhara and Samarkand were further adorned with superb madrassas and mosques. Many of these suffered destruction at the hands of the Mongols in the 13th century, but Timur and his Timurid successors rebuilt the cities and added numerous impressive buildings during the late-14th and early-15th centuries. Further superb buildings were added to these cities by the Shaybanids during the 16th century, yet thereafter neglect by subsequent rulers, and the drying up of Silk Roads trade, meant that, by the mid-18th century when expansive Tsarist Russia began to incorporate these regions into its empire, many of the great pre- and post-Islamic buildings of Central Asia had fallen into ruin. -

Longines Turf Winner Notes- Owner, Aga Khan

H.H. Aga Khan Born: Dec. 13, 1936, Geneva, Switzerland Family: Children, Rahim Aga Khan, Zahra Aga Khan, Aly Muhammad Aga Khan, Hussain Aga Khan Breeders’ Cup Record: 15-2-0-2 | $3,447,400 • Billionaire, philanthropist and spiritual leader, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV is also well known as an owner and breeder of Thoroughbreds. • Has two previous Breeders’ Cup winners – Lashkari (GB), captured the inaugural running of Turf (G1) in 1984 and Kalanisi (IRE) won 2000 edition of race. • This year, is targeting the $4 million Longines Turf with his good European filly Tarnawa (IRE), who was also cross-entered for the $2 million Maker’s Mark Filly & Mare Turf (G1) after earning an automatic entry via the Breeders’ Cup Challenge “Win & You’re In” series upon winning Longines Prix de l’Opera (G1) Oct. 4 at Longchamp. Perfect in three 2020 starts, the homebred also won Prix Vermeille (G1) in September. • Powerhouse on the international racing stage. Has won the Epsom Derby five times, including the record 10-length victory in 1981 by the ill-fated Shergar (GB), who was famously kidnapped and never found. In 2000, Sinndar (IRE) became the first horse to win Epsom Derby, Irish Derby (G1) and Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe (G1) the same season. In 2008, his brilliant unbeaten filly Zarkava (IRE) won the Arc and was named Europe’s Cartier Horse of the Year. • Trainers include Ireland-based Dermot Weld, Michael Halford and beginning in 2021 former Irish champion jockey Johnny Murtagh, who rode Kalanisi to his Breeders’ Cup win, and France-based Alain de Royer-Dupre, Jean-Claude Rouget, Mikel Delzangles and Francis-Henri Graffard • Almost exclusively races homebreds but is ever keen to acquire new bloodlines, evidenced by acquisition of the late Francois Dupre's stock in 1977, the late Marcel Boussac’s in 1978 and Jean-Luc Lagardere’s in 2005. -

The Traditional Arts and Crafts of Turnery Or Mashrabiya

THE TRADITIONAL ARTS AND CRAFTS OF TURNERY OR MASHRABIYA BY JEHAN MOHAMED A Capstone submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Art Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Martin Rosenberg And Approved by ______________________________ Dr. Martin Rosenberg Camden, New Jersey May 2015 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT The Traditional Arts and Crafts of Turnery or Mashrabiya By JEHAN MOHAMED Capstone Director: Dr. Martin Rosenberg For centuries, the mashrabiya as a traditional architectural element has been recognized and used by a broad spectrum of Muslim and non-Muslim nations. In addition to its aesthetic appeal and social component, the element was used to control natural ventilation and light. This paper will analyze the phenomenon of its use socially, historically, artistically and environmentally. The paper will investigate in depth the typology of the screen; how the different techniques, forms and designs affect the function of channeling direct sunlight, generating air flow, increasing humidity, and therefore, regulating or conditioning the internal climate of a space. Also, in relation to cultural values and social norms, one can ask how the craft functioned, and how certain characteristics of the mashrabiya were developed to meet various needs. Finally, the study of its construction will be considered in relation to artistic representation, abstract geometry, as well as other elements of its production. ii Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………….……….…..ii List of Illustrations………………………………………………………………………..iv Introduction……………………………………………….…………………………….…1 Chapter One: Background 1.1. Etymology………………….……………………………………….……………..3 1.2. Description……………………………………………………………………...…6 1.3. -

Backstreets & Bazaars of Uzbekistan 2020

Backstreets & Bazaars of Uzbekistan 2020 ! Backstreets & Bazaars of Uzbekistan A Cultural & Culinary Navruz Adventure 2020 – Cultural Series – 10 Days March 16-25, 2020 Taste your way through the vibrant heart of the Silk Road, Uzbekistan, on a culinary and cultural caravan held during the height of Navruz. A centuries-old festival, Navruz is a joyous welcoming of the return of spring and the beginning of a new year, when families and local communities celebrate over sumptuous feasts, songs and dance. Beginning in the modern capital of Tashkent, introduce your palate to the exciting tastes of Uzbek cuisine during a meeting with one of the city’s renowned chefs. Explore the ancient architecture of three of the most celebrated Silk Road oases – Bukhara, Khiva and Samarkand – and browse their famed markets and bazaars for the brilliant silks, ceramics and spices that gave the region its exotic flavor. Join with the locals in celebrating Navruz at a special community ceremony, and gather for a festive Navruz dinner. Along the way, participate in hands-on cooking classes and demonstrations, meet with master artisans in their workshops, dine with local families in their private homes and discover the rich history, enduring traditions and abundant hospitality essential to everyday Uzbek culture. © 1996-2020 MIR Corporation 85 South Washington St, Ste. 210, Seattle, WA 98104 • 206-624-7289 • 206-624-7360 FAX • Email [email protected] 2 Daily Itinerary Day 1, Monday, March 16 Arrive Tashkent, Uzbekistan Day 2, Tuesday, March 17 Tashkent • fly to Urgench • Khiva Day 3, Wednesday, March 18 Khiva Day 4, Thursday, March 19 Khiva • Bukhara Day 5, Friday, March 20 Bukhara • celebration of Navruz Day 6, Saturday, March 21 Bukhara • celebration of Navruz Day 7, Sunday, March 22 Bukhara • Gijduvan • Samarkand Day 8, Monday, March 23 Samarkand Day 9, Tuesday, March 24 Samarkand • day trip to Urgut • train to Tashkent Day 10, Wednesday March 25 Depart Tashkent © 1996-2020 MIR Corporation 85 South Washington St, Ste.