Gilbert Ryle and the Ethical Impetus for Know-How

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Sociology and Anthropology of Evil: Tricksterology

“Because evil is a term fraught with religious overtones, it tends to be under- theorized in our largely secular contemporary culture. Yet something like evil continues to exist, arguably more forcefully today than ever, so the authors of this timely and important book assert. They argue boldly that understanding the continued presence of evil in the modern world requires reconceiving evil through the mythical figure of the trickster, a cross-cultural symbol that repre- sents the perennial temptation to ignore the inherent limits of human thought and action. A wide ranging study that draws on multiple disciplinary sources, Horvath and Szakolczai illustrate forcefully how contemporary efforts to maximize productivity across all sectors of our social order violates the ethos of limits, and only liberates further the forces of destruction. In an age of increasingly mindless (and therefore runaway) processes, we would do well to heed the message of this significant study.” – Gilbert Germain, Professor of Political Thought at the University of Prince Edward Island, Canada “A complex and timely meditation on the nature of evil in human societies, reaching back into the distant past – while not all will agree with its methods or conclusions, this book offers provocative ideas for consideration by anthro- pologists, philosophers, and culture historians.” – David Wengrow, Professor of Comparative Archaeology, University College London, UK “This book offers an original and thought-provoking engagement with a problem for which we still lack adequate perspectives: the disastrous experience of advanced modernity with what we can provisionally call demonic power.” – Johann Arnason, Emeritus Professor of Sociology, La Trobe University, Australia “Horvath and Szakolczai provide a remarkable service in bringing the neglec- ted figure of the trickster into the spotlight. -

Syllabus SAS2B: Scandinavian Literature – 20Th and 21St Century Scandinavian Area Studies – Spring 2019

December 1, 2018 Syllabus SAS2B: Scandinavian Literature – 20th and 21st Century Scandinavian Area Studies – Spring 2019. Please note that minor changes might be made in the final version of the syllabus. Course instructor: Associate Professor Anders M. Gullestad ([email protected]) Office: Room 420 (HF) Office hours: Thursdays 14-15 Lectures: Mondays 12.15-14, room K at Sydneshaugen skole Student advisor: Guro Sandnes ([email protected]) Exam advisor: Vegard Sørhus ([email protected], room 356) ECTS: 15 Language of instruction: English (spoken and written proficiency is required) Course unit level: Bachelor Grading scale: A-F READING MATERIALS: 1. Novels: The following novels can all be found at the university bookstore, Akademia: Johannes V. Jensen: The Fall of the King [1901], transl. Alan G. Bower. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 2011. Knut Hamsun: The Ring is Closed [1936], transl. Robert Ferguson. London: Souvenir Press, 2010. Karin Boye: Kallocain [1940], transl. Gustav Lannestock and with a foreword by Richard B. Vowles. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002. Dag Solstad: Shyness and Dignity [1994], transl. Sverre Lyngstad. London: Harvill Sacker, 2006. Per Petterson: Out Stealing Horses [2003], transl. Anne Born. London: Vintage Books, 2006. Karl Ove Knausgaard: My Struggle: Book 1 [2009], transl. Don Bartlett. New York: Farar, Straus & Giroux, 2013. Helle Helle: This Should Be Written in the Present Tense [2011], transl. Martin Aitken. London: Vintage Books, 2015. Jonas Hassen Khemiri: Everything I Don’t Remember [2015], transl.Rachel Willson- Broyles. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016. 2. Poems: A selection of poems by important Scandinavian authors. The poems will be handed out in class or made available at Mitt UiB ahead of the lectures. -

Ryle and the Para-Mechanical

BRYAN BENHAM Ryle and the Para-mechanical WINNER OF mE 1999 LARRY TAYLOR MEMORIAL AWARD The thesis of this paper is the unconventional claim that Gilbert Ryle is not a logical behaviorist. The popular account ofRyle clearly places his work in The Concept ofMind (1949) in the camp oflogical behaviorist.! The object of this paper, however, will be to illustrate how the conventional interpretation of Ryle is misleading. My argument is not an exhaustive account of Ryle, but serves as a starting point for understanding Ryle outside of the behaviorist label that is usually attached to his work. The argument is straightforward. First, it is apparent on any reasonable construal that logical behaviorism is a reductionist project about the mind. The basic claim of logical behaviorism is that statements containing mental vocabulary can be analyzed into statements containing only the vocabulary of physical behavior. Second, any reasonable account ofRyle will show that he is not a reductionist about the mental, in fact he was adamantly anti-reductionist about the mind. Once these two claims are established it follows quite readily that Ryle was not a logical behaviorist. The first premise is uncontroversial. Anyone familiar with logical behaviorism understands that its aim is to show that mental terminology doesn't refer to unobserved phenomena, supposedly in the head of the person described, but rather to the observed physical behaviors or dispositions to behave (Hempel 1999). In fact, in its strict formulation, logical behaviorism claims that mental terminology signifies only these observed behaviors or dispositions to behave. Thus, I will take it as a reasonably established claim that logical behaviorism is reductionist about the mind. -

The Practical Origins of Ideas

OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 19/1/2021, SPi The Practical Origins of Ideas Genealogy as Conceptual Reverse-Engineering MATTHIEU QUELOZ 1 OUP CORRECTED AUTOPAGE PROOFS – FINAL, 19/1/2021, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Matthieu Queloz 2021 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2021 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The pre-press of this publication was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of this licence should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2020951579 ISBN 978–0–19–886870–5 DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198868705.001.0001 Printed and bound in the UK by TJ Books Limited Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Nobel Prize Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 423 CS 202 277 AUTHOR Hubbard, Terry E., Comp. TITLE Nobel Prize Literature; A Selection of the Works of Forty-Four Nobel Prize Winning Authors in the Library of Dutchess Community College, with Biographical and Critical Sketches. PUB DATE Nov 72 NOTE 42p.; Not available in hard copy due tc marginal legibility of original document EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Authors; *Bibliographies; *English Instruction; Fiction; Higher Education; Poetry; *Reading Materials; Secondary Education; *Twentieth Century Literature; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS Nobel (Alfred); *Nobel Literature Prize ABSTRACT This bibliography is a compilation of works by 44 Nobel Prize winning authors presently available at the Dutchess Community College library. Each entry describes the piece of literature for which the author received an award, provides a brief sketch of the writer, includes a commentary on the themes of major works, and lists the writer's works. An introduction to the bibliography provides background information on the life of Alfred Nobel and the prizes made available to individuals who have made contributions toward humanistic ends. The bibliography may be used as a reading guide to some classics of twentieth century literature or as an introduction to important authors. Authors listed include Samuel Beckett, Henri Bergson, Pearl Buck, Ivan Bunin, Albert Camus, and 7.S. Eliot.(RE) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). -

Premio Nobel Per La Letteratura

Premio Nobel per la letteratura Bibliografia A cura della Biblioteca Cantonale di Bellinzona Novembre 2017 Il 5 ottobre 2017 Kazuo Ishiguro ha vinto il Premio Nobel per la letteratura. E’ stata l’occasione per scoprire o ri-scoprire questo importante scrittore inglese di origine giapponese. Ma quali sono gli scrittori premiati in questi anni? Dal 1901 ogni anno un autore viene onorato con questo significativo premio. Proponiamo con questa bibliografia le opere di scrittori vincitori del Premio Nobel, presenti nel fondo della Biblioteca cantonale di Bellinzona, e nel caso in cui la biblioteca non possedesse alcun titolo di un autore, le opere presenti nel catalogo del Sistema bibliotecario ticinese. Gli autori sono elencati cronologicamente decrescente a partire dall’anno in cui hanno vinto il premio. Per ogni autore è indicato il link che rinvia al catalogo del Sistema bibliotecario ticinese. 2017 Kazuo Ishiguro 2016 Bob Dylan 2015 Svjatlana Aleksievič 2014 Patrick Modiano 2013 Alice Munro 2012 Mo Yan 2011 Tomas Tranströmer 2010 Mario Vargas Llosa 2009 Herta Müller 2008 Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio 2007 Doris Lessing 2006 Orhan Pamuk 2005 Harold Pinter 2004 Elfriede Jelinek 2003 John Maxwell Coetzee 2002 Imre Kertész 2001 Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul 2000 Gao Xingjian 1999 Günter Grass 1998 José Saramago 1997 Dario Fo 1996 Wisława Szymborska 1995 Séamus Heaney 1994 Kenzaburō Ōe 1993 Toni Morrison 1992 Derek Walcott 1991 Nadine Gordimer 1990 Octavio Paz 1989 Camilo José Cela 1988 Naguib Mahfouz 1987 Iosif Aleksandrovič Brodskij 1986 Wole -

THE MYTH of LOGICAL BEHAVIOURISM and the ORIGINS of the IDENTITY THEORY Sean Crawford the Identity Theory's Rapid Rise to Asce

THE MYTH OF LOGICAL BEHAVIOURISM AND THE ORIGINS OF THE IDENTITY THEORY Sean Crawford The identity theory’s rapid rise to ascendancy in analytic philosophy of mind during the late 1950s and early 1960s is often said to have constituted a sea change in perspective on the mind-body problem. According to the standard story, logical or analytical behaviourism was analytic philosophy of mind’s first original materialist-monist solution to the mind-body problem and served to reign in various metaphysically extravagant forms of dualism and introspectionism. It is understood to be a broadly logico-semantic doctrine about the meaning or definition of mental terms, namely, that they refer to dispositions to engage in forms of overt physical behaviour. Logical/analytical behaviourism then eventually gave way, so the standard story goes, in the early 1960s, to analytical philosophy’s second original materialist-monist solution to the mind-body problem, the mind-brain identity theory, understood to be an ontological doctrine declaring states of sensory consciousness to be physical states of the brain and wider nervous system. Of crucial importance here is the widely held notion that whereas logical behaviourism had proposed an identity between the meanings of mental and physical- behavioural concepts or predicates—an identity that was ascertainable a priori through conceptual analysis—the identity theory proposed an identity between mental and physical properties, an identity that could only be established a posteriori through empirical scientific investigation. John Searle (2004) has recently described the transition thus: [logical behaviourism] was gradually replaced among materialist-minded philosophers by a doctrine called “physicalism,” sometimes called the “identity theory.” The physicalists said that Descartes was not wrong, as the logical behaviourists had claimed, as a matter of logic, but just as a matter of fact. -

An Interview with Donald Davidson

An interview with Donald Davidson Donald Davidson is an analytic philosopher in the tradition of Wittgenstein and Quine, and his formulations of action, truth and communicative interaction have generated considerable debate in philosophical circles around the world. The following "interview" actually took place over two continents and several years. It's merely a part of what must now be literally hundreds of hours of taped conversations between Professor Davidson and myself. I hope that what follows will give you a flavor of Donald Davidson, the person, as well as the philosopher. I begin with some of the first tapes he and I made, beginning in Venice, spring of 1988, continuing in San Marino, in spring of 1990, and in St Louis, in winter of 1991, concerning his induction into academia. With some insight into how Professor Davidson came to the profession, a reader might look anew at some of his philosophical writings; as well as get a sense of how the careerism unfortunately so integral to academic life today was so alien to the generation of philosophers Davidson is a member of. The very last part of this interview is from more recent tapes and represents Professor Davidson's effort to try to make his philosophical ideas available to a more general audience. Lepore: Tell me a bit about the early days. Davidson: I was born in Springfield, Massachusetts, on March 6, 1917 to Clarence ("Davie") Herbert Davidson and Grace Cordelia Anthony. My mother's father's name was "Anthony" but her mother had married twice and by coincidence both her husbands were named "Anthony". -

English Philosophy in the Fifties

English Philosophy in the Fifties Jonathan Ree If you asked me when was the best time for philosophy in possibly unconscious, as with the contents of the books England in the twentieth century-forprofessional, academic which were destined to become classics. For these reasons, philosophy, that is - I would answer: the fifties, without a I have not engaged with the high-altitude synoptic critiques doubt. And: the fifties, alas. * Under the leadership of - notably those ofMarc use andAnderson - to which Oxford Gilbert Ryle and f.L. Austin, the career philosophers ofthat philosophy has been subjected, either.} period had their fair share of bigotry and evasiveness of The story I tell is meant to be an argument as well as a course; but they also faced up honestly and resourcefully to factual record. It shows that although the proponents ofthe some large and abidingly important theoretical issues. Oxford philosophical revolution prided themselves on their Their headquarters were at that bastion of snobbery and clarity, they never managed to be clear about what their reaction, Oxford University; and by today's standards they revolution amounted to. In itself this is not remarkable, were shameless about their social selectness. They also perhaps; but what is strange is that they were not at all helped philosophy on its sad journey towards being an bothered by what was, one might have thought, quite an exclusively universitarian activity. But still, many of them important failure. This nonchalance corresponded, I be tried to write seriously and unpatronisingly for a larger lieve, to their public-school style - regressive, insiderish, public, and some of them did it with outstanding success. -

The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle

THE PHILOSOPHICAL DEVELOPMENT OF GILBERT RYLE A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings © Charlotte Vrijen 2007 Illustrations front cover: 1) Ryle’s annotations to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus 2) Notes (miscellaneous) from ‘the red box’, Linacre College Library Illustration back cover: Rodin’s Le Penseur RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Wijsbegeerte aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 14 juni 2007 om 16.15 uur door Charlotte Vrijen geboren op 11 maart 1978 te Rolde Promotor: Prof. Dr. L.W. Nauta Copromotor: Prof. Dr. M.R.M. ter Hark Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. Dr. D.H.K. Pätzold Prof. Dr. B.F. McGuinness Prof. Dr. J.M. Connelly ISBN: 978-90-367-3049-5 Preface I am indebted to many people for being able to finish this dissertation. First of all I would like to thank my supervisor and promotor Lodi Nauta for his comments on an enormous variety of drafts and for the many stimulating discussions we had throughout the project. He did not limit himself to deeply theoretical discussions but also saved me from grammatical and stylish sloppiness. (He would, for example, have suggested to leave out the ‘enormous’ and ‘many’ above, as well as by far most of the ‘very’’s and ‘greatly’’s in the sentences to come.) After I had already started my new job outside the academic world, Lodi regularly – but always in a pleasant way – reminded me of this other job that still had to be finished. -

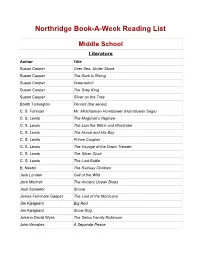

Northridge Book-A-Week Reading List

Northridge Book-A-Week Reading List Middle School Literature Author Title Susan Cooper Over Sea, Under Stone Susan Cooper The Dark is Rising Susan Cooper Greenwitch Susan Cooper The Grey King Susan Cooper Silver on the Tree Booth Tarkington Penrod (the series) C. S. Forester Mr. Midshipman Hornblower (Hornblower Saga) C. S. Lewis The Magician's Nephew C. S. Lewis The Lion the Witch and Wardrobe C. S. Lewis The Horse and His Boy C. S. Lewis Prince Caspian C. S. Lewis The Voyage of the Dawn Treader C. S. Lewis The Silver Chair C. S. Lewis The Last Battle E. Nesbit The Railway Children Jack London Call of the Wild Jack Mitchell The Ancient Ocean Blues Jack Schaefer Shane James Fenimore Cooper The Last of the Mohicans Jim Kjelgaard Big Red Jim Kjelgaard Snow Dog Johann David Wyss The Swiss Family Robinson John Knowles A Separate Peace John Steinbeck The Red Pony Jules Verne Around the World in 80 Days Jules Verne 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea Jules Verne The Mysterious Island Kenneth Grahame The Wind in the Willows Lew Wallace Ben Hur Lois Lowry The Giver Marjorie Rowlings The Yearling Mark Twain A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court Mark Twain The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Mildred Taylor Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry Patricia Treese A Man for Others (St. M. Kolbe) Ralph Moody Little Britches: Father and I Were Ranchers (and series) Robb White Up Periscope Robert Louis Stevenson Treasure Island William O. Steele The Lone Hunt William O. Steele Trail Through Danger William O. -

! ! ! Alienistmagazine5.Indd

1 2 3 4 5 Michael Rowland, from the series SPACE COW (2019) 6 7 8 Political power comes into being through the “grant,” by an absolutist authority, of “individual agency” – of socalled freedom of will – which requires a certain theatre, a performance on the part of the subject acknowledging that such a freedom is indeed within the grant of power in the fi rst place. This performance takes the form of an exchange in which a capital authority over life & death is abrogated into political subjectivity. By such dialectical sleight of hand, power indeed asserts its claim over, & obtains at a discount, the feudal rights to the freedom of the individual, & to the idea of freedom as such. Whatever thus presents itself as exempted or excluded from the domain of the political, is so solely upon this foundation. For this reason we must seek the alienation of the subject not in some social imposition from which it may one day be freed by a political act, but in its very ontology. The individual subject is itself nothing other than the signifi er of a constitutive alienation & the embodiment of an insidious contract from which there is no release. This is the true meaning of subjectivity, compromised at birth, weaned upon the most Oedipal of bad faiths. It bears the sign of the asymmetry of power inscribed upon its brow & dreams constantly of becoming its opposite. And from this stems every impulse & logic of resistance. 9 10 THE ALIENIST TENDENCY A breach has been made with the past, bringing into perspective new aspects of alienation: the morphology of a dead technical civilisation in the fi ctional process of resurrection! And we are returning again to the “honesty of thought & feeling”? This holographic world is being shaken out of its torpor by a four-billion- year-old technology.