University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collection

University of Oklahoma Libraries Western History Collection Charles C. Bush, II, Collection Bush, Charles C., II. Papers, 1749–1965. 5 feet. Professor. Instructional materials (1749–1965) for college history courses; student papers (1963); manuscripts (n.d.) and published materials (1941–1960) regarding historical events; and correspondence (1950–1965) to and from Bush regarding historical events and research, along with an original letter (1829) regarding Tecumseh and the Battle of the Thames in 1813, written by a soldier who participated. Instructional Materials Box 1 Folder: 1. Gilberth, Keith Chesterton (2 copies), n.d. 2. The Boomer Movement Part 1, Chapters 1 and 2, 1870-1880. 3. Washington and Braddock, 1749-1755. 4. Washita (1) [The Battle of], 1868. 5. Cheyenne-Arapaho Disturbones-Ft. Reno, 1884-1885. 6. 10th Cav. Bibb and Misel, 1866-1891 1 Pamphlet "Location of Classes-Library of Congress", 1934 1 Pamphlet "School Books and Racial Antagonism" R. B. Elfzer, 1937 7. Speech (notes) on Creek Crisis Rotary Club, Spring '47, 1828-1845. 8. Speech-Administration Looks at Fraternities (2 copies), n.d. 9. Speech YM/WCA "Can Education Save Civilization", n.d. 10. Durant Commencement Speech, 1947. 11. Steward et al Army, 1868-1879. 12. ROTC Classification Board, 1952-1954. 13. Periodical Material, 1888-1906. 14. The Prague News Record - 50th Anniversary, 1902-1951 Vol. 1 7/24/02 No. 1 Vol. 50 8/23/51 No. 1 (2 copies) 15. Newspaper - The Sunday Oklahoma News - Sept. 11 (magazine section) "Economic Conditions of the South", 1938 16. Rockefeller Survey - Lab. Misc. - Course 112 Historic sites in Anadarko and Caddo Counties, Oklahoma - Oklahoma Historical Society, 1884 17. -

The Death of the Socialist Party. by J

Engdahl: The Death of the Socialist Party [Oct. 1924] 1 The Death of the Socialist Party. by J. Louis Engdahl Published in The Liberator, v. 7, no. 10, whole no. 78 (October 1924), pp. 11-14. This year, 1924, will be notable in American It was at that time that I had a talk with Berger, political history. It will record the rise and the fall of enjoying his first term as the lone Socialist Congress- political parties. There is no doubt that there will be a man. He pushed the Roosevelt wave gently aside, as if realignment of forces under the banners of the two it were unworthy of attention. old parties, Republican and Democratic. The Demo- “In order to live, a political party must have an cratic Party is being ground into dust in this year’s economic basis,” he said. “The Roosevelt Progressive presidential struggle. Wall Street, more than ever, sup- Party has no economic basis. It cannot live.” That ports the Republican Party as its own. Middle class settled Roosevelt in Berger’s usual brusque style. elements, with their bourgeois following in the labor It is the same Berger who this year follows movement, again fondly aspire to a third party, a so- unhesitatingly the LaFollette candidacy, the “Roose- called liberal or progressive party, under the leader- velt wave” of 1924. To be sure, the officialdom of or- ship of Senator LaFollette. This is all in the capitalist ganized labor is a little more solid in support of LaFol- camp. lette in 1924 than it was in crawling aboard the Bull For the first time, this year, the Communists are Moose bandwagon in 1912. -

Red Dirt Resistance: Oklahoma

RED DIRT RESISTANCE: OKLAHOMA EDUCATORS AS AGENTS OF CHANGE By LISA LYNN Bachelor of Arts in Psychology University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 1998 Master of Science in Applied Behavioral Studies Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 2001 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2018 RED DIRT RESISTANCE: OKLAHOMA EDUCATORS AS AGENTS OF CHANGE Dissertation Approved: Jennifer Job, Ph.D. Dissertation Adviser Pamela U. Brown, Ph.D. Erin Dyke, Ph.D. Lucy E. Bailey, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Job for her tireless input, vision, and faith in this project. She endured panicked emails and endless questions. Thank you for everything. I would also like to thank Dr. Erin Dyke, Dr. Pam Brown, and Dr. Lucy Bailey for their support and words of encouragement. Each of you, in your own way, gently stretched me to meet the needs of this research and taught me about myself. Words are inadequate to express my gratitude. I would also like the thank Dr. Moon for his passionate instruction and support, and Dr. Wang for her guidance. I am particularly grateful for the friendship of my “cohort”, Ana and Jason. They and many others carried me through the rough spots. I want to acknowledge my mother and father for their unwavering encouragement and faith in me. Finally, I need to thank my partner, Ron Brooks. We spent hours debating research approaches, the four types of literacy, and gender in education while doing dishes, matching girls’ socks, and walking the dogs. -

Betting the Farm: the First Foreclosure Crisis

AUTUMN 2014 CT73SA CT73 c^= Lust Ekv/lll Lost Photographs _^^_^^ Betting the Farm: The First Foreclosure Crisis BOOK EXCERPr Experience it for yourself: gettoknowwisconsin.org ^M^^ Wisconsin Historic Sites and Museums Old World Wisconsin—Eagle Black Point Estate—Lake Geneva Circus World—Baraboo Pendarvis—Mineral Point Wade House—Greenbush !Stonefield— Cassville Wm Villa Louis—Prairie du Chien H. H. Bennett Studio—Wisconsin Dells WISCONSIN Madeline Island Museum—La Pointe First Capitol—Belmont HISTORICAL Wisconsin Historical Museum—Madison Reed School—Neillsville SOCIETY Remember —Society members receive discounted admission. WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Director, Wisconsin Historical Society Press Kathryn L. Borkowski Editor Jane M. de Broux Managing Editor Diane T. Drexler Research and Editorial Assistants Colleen Harryman, John Nondorf, Andrew White, John Zimm Design Barry Roal Carlsen, University Marketing THE WISCONSIN MAGAZINE OF HISTORY (ISSN 0043-6534), published quarterly, is a benefit of membership in the Wisconsin Historical Society. Full membership levels start at $45 for individuals and $65 for 2 Free Love in Victorian Wisconsin institutions. To join or for more information, visit our website at The Radical Life of Juliet Severance wisconsinhistory.org/membership or contact the Membership Office at 888-748-7479 or e-mail [email protected]. by Erikajanik The Wisconsin Magazine of History has been published quarterly since 1917 by the Wisconsin Historical Society. Copyright© 2014 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. 16 "Give 'em Hell, Dan!" ISSN 0043-6534 (print) How Daniel Webster Hoan Changed ISSN 1943-7366 (online) Wisconsin Politics For permission to reuse text from the Wisconsin Magazine of by Michael E. -

![The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [March 4, 1922] 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1973/the-green-corn-rebellion-in-oklahoma-march-4-1922-1-421973.webp)

The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [March 4, 1922] 1

White: The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [March 4, 1922] 1 The Green Corn Rebellion in Oklahoma [events of Aug. 3, 1917] by Bertha Hale White † Published in The New Day [Milwaukee], v. 4, no. 9, whole no. 91 (March 4, 1922), pg. 68. The story of the wartime prisoners of Oklahoma ceived the plan of organizing, of banding themselves is one of the blind, desperate rebellion of a people together to fight the exactions of landlord and banker. driven to fury and despair by conditions which are The result of these efforts was a nonpolitical or- incredible in this stage of our so-called civilization. ganization known as the Working Class Union. It had Even the lowliest of the poor in the great industrial but one object — to force downward rents and inter- centers of the country have no conception of the depths est rates. The center of the movement seems to have of misery and poverty that is the common lot of the been the Seminole country, where even today one tenant farmer of the South. meets more frequently the Indian than the white man. As long as we can remember, we have heard of It has been asserted by authoritative people that their exploitation. We are told that the tenant must not 1 in 15 of these tenants can read or write. It is mortgage his crop before he can obtain the seed to put obvious that very little of what is happening in the into the ground; that when the harvesting is over out world is ever very closely understood by the majority of the fruits of his labor he can pay only a part of the of them. -

POST Tilt W 0 RLII* C 0111C1L — Telephone: Gramercy 7-8534 112 E

f. m : m POST tilt W 0 RLII* C 0111C1L _ — Telephone: GRamercy 7-8534 _ 112 E. 19lh STREET. NEW YORK J/ . ¿äät&b, /KO Oswald Garrison Villard Treasurer National Committee Man- W. Hillyer Executive Director Helen Alfred Oscar Ameringer March 6, 1942 Harry Elmer Barnes Irving Barshop Charles F. Boss, Jr. Allan Knight Chalmers President Franklin D. Roosevelt r FILED Travers Clement The White House i Bv v, s. Dorothy Detzer Washington, D. C. »PR 3 Elisabeth Gilman Albert W. Hamilton Dear Mr. Roosevelt: Sidney Hertzberg John Haynes Holmes I have been instructed, "by our Governing Committee Abraham Kaufman to send you the following resolution which was unanimously Maynard C. Krueger adopted at our meeting this week: Margaret I. I^amont l-ayle Lane «Recognizing the real danger of subversive activities W. Jett Lauck among aliens of the West Coast, we nevertheless believe Frederick J. Libby that the Presidential order giving power to generals in Albert J. Livezey command of military departments to evacuate any or all Mrs. Dana Malone aliens or citizens from any districts which may be desig- Lenore G. Marshall nated as military constitutes a danger to American freedom Mrs. Seth M. Milliken and to her reputation for fair play throughout the world Amicus Most far greater than any danger which it is designed to cure. A. J. Muste We, therefore, ask the President for a modification of Kay Newton the order so that, at the least, evacuation of citizens will Mildred Scott Olmsted depend upon evidence immediately applicable to the person Albert W. Palmer or persons evacuated. -

For All the People

Praise for For All the People John Curl has been around the block when it comes to knowing work- ers’ cooperatives. He has been a worker owner. He has argued theory and practice, inside the firms where his labor counts for something more than token control and within the determined, but still small uni- verse where labor rents capital, using it as it sees fit and profitable. So his book, For All the People: The Hidden History of Cooperation, Cooperative Movements, and Communalism in America, reached expectant hands, and an open mind when it arrived in Asheville, NC. Am I disappointed? No, not in the least. Curl blends the three strands of his historical narrative with aplomb, he has, after all, been researching, writing, revising, and editing the text for a spell. Further, I am certain he has been responding to editors and publishers asking this or that. He may have tired, but he did not give up, much inspired, I am certain, by the determination of the women and men he brings to life. Each of his subtitles could have been a book, and has been written about by authors with as many points of ideological view as their titles. Curl sticks pretty close to the narrative line written by worker own- ers, no matter if they came to work every day with a socialist, laborist, anti-Marxist grudge or not. Often in the past, as with today’s worker owners, their firm fails, a dream to manage capital kaput. Yet today, as yesterday, the democratic ideals of hundreds of worker owners support vibrantly profitable businesses. -

The War to End All Wars. COMMEMORATIVE

FALL 2014 BEFORE THE NEW AGE and the New Frontier and the New Deal, before Roy Rogers and John Wayne and Tom Mix, before Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse and Felix the Cat, before the TVA and TV and radio and the Radio Flyer, before The Grapes of Wrath and Gone with the Wind and The Jazz Singer, before the CIA and the FBI and the WPA, before airlines and airmail and air conditioning, before LBJ and JFK and FDR, before the Space Shuttle and Sputnik and the Hindenburg and the Spirit of St. Louis, before the Greed Decade and the Me Decade and the Summer of Love and the Great Depression and Prohibition, before Yuppies and Hippies and Okies and Flappers, before Saigon and Inchon and Nuremberg and Pearl Harbor and Weimar, before Ho and Mao and Chiang, before MP3s and CDs and LPs, before Martin Luther King and Thurgood Marshall and Jackie Robinson, before the pill and Pampers and penicillin, before GI surgery and GI Joe and the GI Bill, before AFDC and HUD and Welfare and Medicare and Social Security, before Super Glue and titanium and Lucite, before the Sears Tower and the Twin Towers and the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building, before the In Crowd and the A Train and the Lost Generation, before the Blue Angels and Rhythm & Blues and Rhapsody in Blue, before Tupperware and the refrigerator and the automatic transmission and the aerosol can and the Band-Aid and nylon and the ballpoint pen and sliced bread, before the Iraq War and the Gulf War and the Cold War and the Vietnam War and the Korean War and the Second World War, there was the First World War, World War I, The Great War, The War to End All Wars. -

Finding Aid Prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION THE RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTION Finding aid prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C. - Library of Congress - 1995 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK ANtI SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISIONS RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTIONS The Radical Pamphlet Collection was acquired by the Library of Congress through purchase and exchange between 1977—81. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 25 Number of items: Approx: 3465 Scope and Contents Note The Radical Pamphlet Collection spans the years 1870-1980 but is especially rich in the 1930-49 period. The collection includes pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, posters, cartoons, sheet music, and prints relating primarily to American communism, socialism, and anarchism. The largest part deals with the operations of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), its members, and various “front” organizations. Pamphlets chronicle the early development of the Party; the factional disputes of the 1920s between the Fosterites and the Lovestoneites; the Stalinization of the Party; the Popular Front; the united front against fascism; and the government investigation of the Communist Party in the post-World War Two period. Many of the pamphlets relate to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of CP leaders Earl Browder and William Z. Foster. Earl Browder, party leader be—tween 1929—46, ran for President in 1936, 1940 and 1944; William Z. Foster, party leader between 1923—29, ran for President in 1928 and 1932. Pamphlets written by Browder and Foster in the l930s exemplify the Party’s desire to recruit the unemployed during the Great Depression by emphasizing social welfare programs and an isolationist foreign policy. -

The Crime and Society Issue

FALL 2020 THE CRIME AND SOCIETY ISSUE Can Academics Such as Paul Butler and Patrick Sharkey Point Us to Better Communities? Michael O’Hear’s Symposium on Violent Crime and Recidivism Bringing Baseless Charges— Darryl Brown’s Counterintuitive Proposal for Progress ALSO INSIDE David Papke on Law and Literature A Blog Recipe Remembering Professor Kossow Princeton’s Professor Georgetown’s Professor 1 MARQUETTE LAWYER FALL 2020 Patrick Sharkey Paul Butler FROM THE DEAN Bringing the National Academy to Milwaukee—and Sending It Back Out On occasion, we have characterized the work of Renowned experts such as Professors Butler and Sharkey Marquette University Law School as bringing the world and the others whom we bring “here” do not claim to have to Milwaukee. We have not meant this as an altogether charted an altogether-clear (let alone easy) path to a better unique claim. For more than a century, local newspapers future for our communities, but we believe that their ideas have brought the daily world here, as have, for decades, and suggestions can advance the discussion in Milwaukee broadcast services and, most recently, the internet. And and elsewhere about finding that better future. many Milwaukee-based businesses, nonprofits, and So we continue to work at bringing the world here, organizations are world-class and world-engaged. even as we pursue other missions. To reverse the phrasing Yet Marquette Law School does some things in this and thereby to state another truth, we bring Wisconsin regard especially well. For example, in 2019 (pre-COVID to the world in issues of this magazine and elsewhere, being the point), about half of our first-year students had not least in the persons of those Marquette lawyers been permanent residents of other states before coming who practice throughout the United States and in many to Milwaukee for law school. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

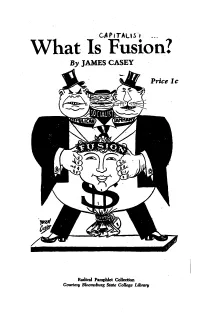

What -Is Fusion? by JAM ES CASEY

CAPiTALIS ' . What -Is Fusion? By JAM ES CASEY 11 -d t Price IIc S. Radical Pampblet Colletion Coutesy Bloomsburg State CoUege Library TRIUMPH AND DISASTER: THE READING SOCIALISTS IN POWER AND DECLINE, 1932-1939-PART II BY KrNNErm E. HENDmcKsoN, JR.' D EFEAT by the fusionists in 1931 did little internal damage to the structure of the Reading socialist movement. As a matter of fact, just the reverse was true. Enthusiasm seemed to intensify and the organization grew.' The party maintained a high profile during this period and was very active in the political and economic affairs of the community, all the while looking forward to the election of 1935 when they would have an op- portunity to regain control of city hall. An examination of these activities, which were conducted for the most part at the branch level, will reveal clearly how the Socialists maintained their organization while they were out of power. In the early 1930s the Reading local was divided into five branches within the city. In the county there were additional branches as well, the number of which increased from four in 1931 to nineteen in 1934. All of these groups brought the rank and file together each week. Party business was conducted, of_ course, but the branch meetings served a broader purpose. Fre- quently, there were lectures and discussions on topics of current interest, along with card parties, dinners, and dances. The basic party unit, therefore, served a very significant social function in the lives of its members, especially important during a period of economic decline when few could afford more than the basic es- sentials of daily life.