CHAPTER XIV DURING the Sudden Preparation for the Action At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

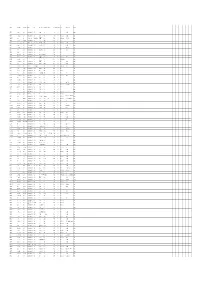

ANNEXE - LISTE DES VOIRIES COMMUNAUTAIRES Communes Voiries VC 304 D'acheux À Bus De La RD 114 À La Limite Du Territoire De Bus 1 291

ANNEXE - LISTE DES VOIRIES COMMUNAUTAIRES Communes voiries VC 304 d'Acheux à Bus de la RD 114 à la limite du territoire de Bus 1 291 ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS VC 306 de Léalvillers à Varennes de la limite du territoire de Léalvillers à la VC 307 de Varennes à Toutencourt 656 VC 307 de Varennes à Toutencourt de la VC 306 à la limite du territoire de Varennes ; voie en totale mitoyenneté 130 avec Varennes VC 10 d'Albert à Bécourt de la sortie d'agglomération à la limite du territoire de Bécourt dont 208 m limitrophe 902 ALBERT Rue Henry Potez, rue Hénon (voie interne de la zone d'activités n°1) 1 050 Rue de l'industrie (voie interne de la zone d'activités) 580 voie interne Zone Henry Potez n°2 230 VC 4 d'Arquèves à Louvencourt de la RD 31 à la limite du territoire de Louvencourt 1 897 ARQUEVES VC 5 de Raincheval à Vauchelles de la limite du territoire de Vauchelles à la limite du territoire de Raincheval 189 AUCHONVILLERS VC 6 d'Auchonvillers à Vitermont de la RD 174 à la limite du territoire communal 754 VC 302 d'Authie à Louvencourt de la RD 152 à la limite du territoire de Louvencourt dont 185 m mitoyen à AUTHIE 2 105 Louvencourt VC 5 d'Authuille à Mesnil-Martinsart de la sortie d'agglomération à la limite du territoire 270 AUTHUILLE VC 3 d’Authuille à Ovillers-la-Boisselle de la sortie d’agglomération à la limite du territoire d’Ovillers 1155 AVELUY VC 4 d'Aveluy à Mesnil de la RD 50 sur sa partie revêtue 400 BAYENCOURT VC 308 de Bayencourt à Coigneux de la sortie d'agglomération à la limite du territoire de Coigneux 552 BAZENTIN VC 4 de Bazentin -

In Memory of the Officers and Men from Rye Who Gave Their Lives in the Great War Mcmxiv – Mcmxix (1914-1919)

IN MEMORY OF THE OFFICERS AND MEN FROM RYE WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THE GREAT WAR MCMXIV – MCMXIX (1914-1919) ADAMS, JOSEPH. Rank: Second Lieutenant. Date of Death: 23/07/1916. Age: 32. Regiment/Service: Royal Sussex Regiment. 3rd Bn. attd. 2nd Bn. Panel Reference: Pier and Face 7 C. Memorial: THIEPVAL MEMORIAL Additional Information: Son of the late Mr. J. and Mrs. K. Adams. The CWGC Additional Information implies that by then his father had died (Kate died in 1907, prior to his father becoming Mayor). Name: Joseph Adams. Death Date: 23 Jul 1916. Rank: 2/Lieutenant. Regiment: Royal Sussex Regiment. Battalion: 3rd Battalion. Type of Casualty: Killed in action. Comments: Attached to 2nd Battalion. Name: Joseph Adams. Birth Date: 21 Feb 1882. Christening Date: 7 May 1882. Christening Place: Rye, Sussex. Father: Joseph Adams. Mother: Kate 1881 Census: Name: Kate Adams. Age: 24. Birth Year: abt 1857. Spouse: Joseph Adams. Born: Rye, Sussex. Family at Market Street, and corner of Lion Street. Joseph Adams, 21 printers manager; Kate Adams, 24; Percival Bray, 3, son in law (stepson?) born Winchelsea. 1891 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 9. Birth Year: abt 1882. Father's Name: Joseph Adams. Mother's Name: Kate Adams. Where born: Rye. Joseph Adams, aged 31 born Hastings, printer and stationer at 6, High Street, Rye. Kate Adams, aged 33, born Rye (Kate Bray). Percival A. Adams, aged 9, stepson, born Winchelsea (born Percival A Bray?). Arthur Adams, aged 6, born Rye; Caroline Tillman, aged 19, servant. 1901 Census: Name: Joseph Adams. Age: 19. Birth Year: abt 1882. -

Memorial at Contalmaison, France

Item no Report no CPC/ I b )03-ClVke *€DINBVRGH + THE CITY OF EDINBURGH COUNCIL Hearts Great War Memorial Fund - Memorial at Contalmaison, France The City of Edinburgh Council 29 April 2004 Purpose of report 1 This report provides information on the work being undertaken by the Hearts Great War Memorial Fund towards the establishment of a memorial at Contalmaison, France, and seeks approval of a financial contribution from the Council. Main report 2 The Hearts Great War Memorial Committee aims to establish and maintain a physical commemoration in Contalmaison, France, in November this year, of the participation of the Edinburgh l!jthand 16th Battalions of the Royal Scots at the Battle of the Somme. 3 Members of the Regiment had planned the memorial as far back as 1919 but, for a variety of reasons, this was not progressed and the scheme foundered because of a lack of funds. 4 There is currently no formal civic acknowledgement of the two City of Edinburgh Battalions, Hearts Great War Memorial Committee has, therefore, revived the plan to establish, within sight of the graves of those who died in the Battle of the Somme, a memorial to commemorate the sacrifice made by Sir George McCrae's Battalion and the specific role of the players and members of the Heart of Midlothian Football Club and others from Edinburgh and the su rround i ng a reas. 5 It is hoped that the memorial cairn will be erected in the town of Contalmaison, to where the 16thRoyal Scots advanced on the first day of the battle of the 1 Somme in 1916. -

Tour Sheets Final04-05

Great War Battlefields Study Tour Briefing Notes & Activity Sheets Students Name briefing notes one Introduction The First World War or Great War was a truly terrible conflict. Ignored for many years by schools, the advent of the National Curriculum and the GCSE system reignited interest in the period. Now, thousands of pupils across the United Kingdom study the 1914-18 era and many pupils visit the battlefield sites in Belgium and France. Redevelopment and urban spread are slowly covering up these historic sites. The Mons battlefields disappeared many years ago, very little remains on the Ypres Salient and now even the Somme sites are under the threat of redevelopment. In 25 years time it is difficult to predict how much of what you see over the next few days will remain. The consequences of the Great War are still being felt today, in particular in such trouble spots as the Middle East, Northern Ireland and Bosnia.Many commentators in 1919 believed that the so-called war to end all wars was nothing of the sort and would inevitably lead to another conflict. So it did, in 1939. You will see the impact the war had on a local and personal level. Communities such as Grimsby, Hull, Accrington, Barnsley and Bradford felt the impact of war particularly sharply as their Pals or Chums Battalions were cut to pieces in minutes during the Battle of the Somme. We will be focusing on the impact on an even smaller community, our school. We will do this not so as to glorify war or the part oldmillhillians played in it but so as to use these men’s experiences to connect with events on the Western Front. -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 by John Bilcliffe edited and amended in 2016 by Peter Nelson and Steve Shannon Part 4 The Casualties. Killed in Action, Died of Wounds and Died of Disease. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License You can download this work and share it with others as long as it is credited, but you can’t change it in any way or use it commercially © John Bilcliffe. Email [email protected] Part 4 Contents. 4.1: Analysis of casualties sustained by The Durham Light Infantry on the Somme in 1916. 4.2: Officers who were killed or died of wounds on the Somme 1916. 4.3: DLI Somme casualties by Battalion. Note: The drawing on the front page of British infantrymen attacking towards La Boisselle on 1 July 1916 is from Reverend James Birch's war diary. DCRO: D/DLI 7/63/2, p.149. About the Cemetery Codes used in Part 4 The author researched and wrote this book in the 1990s. It was designed to be published in print although, sadly, this was not achieved during his lifetime. Throughout the text, John Bilcliffe used a set of alpha-numeric codes to abbreviate cemetery names. In Part 4 each soldier’s name is followed by a Cemetery Code and, where known, the Grave Reference, as identified by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Here are two examples of the codes and what they represent: T2 Thiepval Memorial A5 VII.B.22 Adanac Military Cemetery, Miraumont: Section VII, Row B, Grave no. -

Memorials to Scots Who Fought on the Western Front in World War One

Memorials to Scots who fought on the Western Front in World War One Across Flanders and France there are many memorials to those of all nations Finding the memorials who fell in World War One. This map is intended to assist in identifying those for The map on the next page shows the general location on the the Scots who made the ultimate sacrifice during the conflict. Western Front of the memorials for Scottish regiments or Before we move to France and Flanders, let’s take a look at Scotland’s National battalions. If the memorial is in a Commonwealth War Graves War Memorial. Built following World War One, the memorial stands at the Commission Cemetery then that website will give you directions. highest point in Edinburgh Castle. Designed by Sir Robert Lorimer and funded by donations, the memorial is an iconic building. Inside are recorded the names of all Scots who fell in World War One and all subsequent For other memorials and for road maps you could use an conflicts while serving in the armed forces of the United online map such as ViaMichelin. Kingdom and the Empire, in the Merchant Navy, women’s and nursing services, as well as civilians killed at home and overseas. What the memorials commemorate The descriptions of the memorials in this list are designed to give you a brief outline of what and who is being commemorated. By using the QR code provided you will be taken to a website that will tell you a bit more. Don’t forget there are likely to be many more websites in various formats that will provide similar information and by doing a simple search you may find one that is more suitable for your interest. -

We Remember Those Members of the Lloyd's Community Who Lost Their

Surname First names Rank We remember those members of the Lloyd’s community who lost their lives in the First World War 1 We remember those who lost their lives in the First World War SurnameIntroduction Today, as we do each year, Lloyd’s is holding a But this book is the story of the Lloyd’s men who fought. Firstby John names Nelson, Remembrance Ceremony in the Underwriting Room, Many joined the County of London Regiment, either the ChairmanRank of Lloyd’s with many thousands of people attending. 5th Battalion (known as the London Rifle Brigade) or the 14th Battalion (known as the London Scottish). By June This book, brilliantly researched by John Hamblin is 1916, when compulsory military service was introduced, another act of remembrance. It is the story of the Lloyd’s 2485 men from Lloyd’s had undertaken military service. men who did not return from the First World War. Tragically, many did not return. This book honours those 214 men. Nine men from Lloyd’s fell in the first day of Like every organisation in Britain, Lloyd’s was deeply affected the battle of the Somme. The list of those who were by World War One. The market’s strong connections with killed contains members of the famous family firms that the Territorial Army led to hundreds of underwriters, dominated Lloyd’s at the outbreak of war – Willis, Poland, brokers, members and staff being mobilised within weeks Tyser, Walsham. of war being declared on 4 August 1914. Many of those who could not take part in actual combat also relinquished their This book is a labour of love by John Hamblin who is well business duties in order to serve the country in other ways. -

Cahier Des Charges De La Garde Ambulanciere

CAHIER DES CHARGES DE LA GARDE AMBULANCIERE DEPARTEMENT DE LA SOMME Document de travail SOMMAIRE PREAMBULE ............................................................................................................................. 2 ARTICLE 1 : LES PRINCIPES DE LA GARDE ......................................................................... 3 ARTICLE 2 : LA SECTORISATION ........................................................................................... 4 2.1. Les secteurs de garde ..................................................................................................... 4 2.2. Les lignes de garde affectées aux secteurs de garde .................................................... 4 2.3. Les locaux de garde ........................................................................................................ 5 ARTICLE 3 : L’ORGANISATION DE LA GARDE ...................................................................... 5 3.1. Elaboration du tableau de garde semestriel ................................................................... 5 3.2. Principe de permutation de garde ................................................................................... 6 3.3. Recours à la garde d’un autre secteur ............................................................................ 6 ARTICLE 4 : LES VEHICULES AFFECTES A LA GARDE....................................................... 7 ARTICLE 5 : L'EQUIPAGE AMBULANCIER ............................................................................. 7 5.1 L’équipage ....................................................................................................................... -

Channel Island Headstones for the Website

JOURNAL October 40 2011 The Ulster Tower, Thiepval Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All I do not suppose that the global metal market features greatly in Great War journals and magazines, but we know, sometimes to our cost, that the demand from the emerging economies such as Brazil, China and India are forcing prices up, and not only for newly manufactured metals, but also reclaimed metal. There is a downside in that the higher prices are now encouraging some in the criminal fraternity to steal material from a number of sources. To me the most dangerous act of all is to remove railway trackside cabling, surely a fatal accident waiting to happen, while the cost of repair can only be passed onto the hard-pressed passenger in ticket price rises, to go along with the delays experienced. Similarly, the removal of lead from the roofs of buildings can only result in internal damage, the costs, as in the case of the Morecambe Winter Gardens recently, running into many thousands of pounds. Sadly, war memorials have not been totally immune from this form of criminality and, there are not only the costs associated as in the case of lead stolen from church roofs. These thefts frequently cause anguish to the relatives of those who are commemorated on the vanished plaques. But, these war memorial thefts pale into insignificance by comparison with the appalling recent news that Danish and Dutch marine salvage companies have been bringing up components from British submarine and ships sunk during the Great War, with a total loss of some 1,500 officers and men. -

British 8Th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-1918

Centre for First World War Studies British 8th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-18 by Alun Miles THOMAS Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law January 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Recent years have seen an increasingly sophisticated debate take place with regard to the armies on the Western Front during the Great War. Some argue that the British and Imperial armies underwent a ‘learning curve’ coupled with an increasingly lavish supply of munitions, which meant that during the last three months of fighting the BEF was able to defeat the German Army as its ability to conduct operations was faster than the enemy’s ability to react. This thesis argues that 8th Division, a war-raised formation made up of units recalled from overseas, became a much more effective and sophisticated organisation by the war’s end. It further argues that the formation did not use one solution to problems but adopted a sophisticated approach dependent on the tactical situation. -

The Royal Engineers Journal

The Royal Engineers Journal. More Roads (Waziristan, 1937) . ajor A. E. Armstrong 1 The New Field Company, BE., at Work . Maor D. Harrison 17 Initiative C. Major J. G. 0. Whitehead 27 oderm Methods of Concrete Construction in Quetta Captain H. H. C. Withers and Mr. E. G. Russell 31 D.C.R.E. Finance . * . Major E. Bader 40 Old Fort Henry at Kingston, Ontario . Ronald L. Way 57 Bomb Damage and Repair on the Kan Sui Bridge, Canton-Kowloon Rail vay Colonel G. C. Gowlland 62 The Building of "Prelude" . Lieutenant J. L. Gavin 64 The Rhine-Main-Danube Canal. Maior Prokoph 71 The ersey and Irwe Basin . Stanley Pearson 77 The Application of Soil Mechanics to Road Construction and the Use of Bitumen Emulsion for Stabilization of Soils . Brigadier C. H. Hsswell 89 Some Comments on Brigadier Haswell's Lecture on Soil Stabilization Brigadier-General E. C. Wace 99 Approximate Methods of Squaring the Circle . Major J. G. Heard 104 An Improvised Concrete Testing Machine . S. Arnold 106 Tales ofa alayan Labor Force . "ataacha" 111 Correspondence. Books. Magazines . 119 VOL. LIII. MARCH, 1939. CHATHAM: THE INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINEERS. TELEPHONE: CHATEAM 2669. AGNrTS AND PRINTERS: MACyATS LTD. LONDON: HUGH RIBS, LTD., 5, REGENT STRBET, S.W.I. -C - AllAlI-- C 9 - INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE I' m I XPAME T EXPANDED METAL British Steel :: British Labour Reinforcement for Concrete With a proper combination of "Ex- pamet" Expanded Steel and Concrete, light thin slabbing is obtainable of great strength and fire-resistant efficiency; it effects a considerable reduction in dead-weight of super- structure and in vertical building height, and it is used extensively in any type of building-brick, steel, reinforced concrete, etc. -

Wfdwa-Rsl-181112

SURNAME FIRST NAMES RANK at Death REGIMENT UNIT WHERE BORN BORN STATE HONOURS DOD (DD MMM) YOD (YYYY) COD PLACE OF DEATH COUNTRY A'HEARN Edward John Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Wilcannia NSW 4 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium AARONS John Fullarton Private Australian Infantry, AIF 16th Bn Hillston NSW 11 Jul 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France Manchester, ABBERTON Edmund Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Div Signal Coy England 6 Nov 1918 DOI (Illness, acute) 1 AAH, Harefield England Lancashire ABBOTT Charles Edgar Lance Corporal Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Avoca Victoria 30 May 1916 KIA - France ABBOTT Charles Henry Sapper Australian Engineers 3rd Tunnelling Coy Maryborough Victoria 26 May 1917 DOW (Wounds) In the field France ABBOTT Henry Edgar Private Australian Army Medical Corp10th AFA Burra or Hoylton SA 12 Oct 1917 KIA In the field Belgium ABBOTT Oliver Oswald Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Hoyleton SA 22 Aug 1916 KIA Mouquet Farm France ABBOTT Robert Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Malton, Yorkshire England 25 Jul 1916 KIA France France ABOLIN Martin Private Australian Infantry, AIF 44th Bn Riga Russia 10 Jun 1917 KIA - Belgium ABRAHAM William Strong Private Australian Infantry, AIF 11th Bn Mepunga, WarnnamboVictoria 25 Jul 1916 KIA - France Southport, ABRAM Richard Private Australian Infantry, AIF 28th Bn England 29 Jul 1916 Declared KIA Pozieres France Lancashire ACKLAND George Henry Private Royal Warwickshireshire Reg14th Bn N/A N/A 8 Feb 1919 DOI (Illness, acute) - England Manchester, ACKROYD