RESOLVING JAPAN's MODERN IDENTITY in HAYAO MIYAZAKI's SPIRITED AWAY (2001) by Ljubica Juve Jaich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spirited Away Study Guide

Spirited Away Directed by Hayao Miyazki This study guide suggests cross-curricular activities based on the film Spirited Away by Hanoko Miyazaki. The activities seek to complement and extend the enjoyment of watching the film, while at the same time meeting some of the requirements of the National Curriculum and Scottish Guidelines. The subject area the study guide covers includes Art and Design, Music, English, Citizenship, People in Society, Geography and People and Places. The table below specifies the areas of the curriculum that the activities cover National Curriculum Scottish Guidelines Subject Level Subject Level Animation Art +Design KS2 2 C Art + Investigating Visually and 3 A+B Design Reading 5 A-D Using Media – Level B-E Communicating Level A Evaluating/Appreciating Level D Sound Music KS2 3 A Music Investigating: exploring 4A-D sound Level A-C Evaluating/Appreciating Level A,C,D Setting & English KS2 Reading English Reading Characters 2 A-D Awareness of genre 4 C-I Level B-D Knowledge about language level C-D Setting & Citizenship KS2 1 A-C People People & Needs in Characters 4 A+B In Society Society Level A Japan Geography KS2 2 E-F People & Human Environment 3 A-G Places Level A-B 5 A-B Human Physical 7 C Interaction Level A-D Synopsis When we first meet ten year-old Chihiro she is unhappy about moving to a new town with her parents and leaving her old life behind. She is moody, whiney and miserable. On the way to their new house, the family get lost and find themselves in a deserted amusement park, which is actually a mythical world. -

Modern Life Is Rubbish: Miyazaki Hayao Returns to Old- Fashioned Filmmaking

Volume 7 | Issue 19 | Number 4 | Article ID 3139 | May 09, 2009 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Modern Life is Rubbish: Miyazaki Hayao Returns to Old- Fashioned Filmmaking David McNeill Modern Life is Rubbish: Miyazaki for major Disney releases. Spirited Away, his Hayao Returns to Old-Fashioned Oscar-winning 2001 masterpiece, grossed more in Japan than Titanic and elevated his name Filmmaking into the pantheon of global cinema greats. David McNeill Genius recluse, über-perfectionist, lapsed Marxist, Luddite; like the legendary directors of Hollywood's Golden Age, Miyazaki Hayao’s intimidating reputation is almost as famous as his movies. Mostly, though, Japan's undisputed animation king is known for shunning interviews. So it is remarkable to find him sitting opposite us in Studio Ghibli, the Tokyo animation house he co-founded in 1985, reluctantly bracing himself for the media onslaught that now accompanies each of his new projects. Spirited Away Time magazine has since voted him "one of the most influential Asians of the last six decades". Anticipation then is high for his latest, Ponyo on the Cliff by the Sea, which has taken $160m in ticket sales and been seen by 12 million people in Japan alone, and is now set for release in the United States and Europe. Miyazaki Hayao Once a well-kept secret, Miyazaki's films are increasingly greeted with the hoopla reserved 1 7 | 19 | 4 APJ | JF A stiff, avuncular presence in his tweed suit and math teacher's glasses, Miyazaki is clearly uneasy dealing with the media circus. It's unlikely the 68-year-old has heard of British pop group Blur, but he would undoubtedly agree that Modern Life is Rubbish. -

Joe Hisaishi's Musical Contributions to Hayao Miyazaki's Animated Worlds

Joe Hisaishi’s musical contributions to Hayao Miyazaki’s Animated Worlds A Division III Project By James Scaramuzzino "1 Hayao Miyazaki, a Japanese film director, producer, writer, and animator, has quickly become known for some of the most iconic animated films of the late twentieth to early twenty first century. His imaginative movies are known for fusing modern elements with traditional Japanese folklore in order to explore questions of change, growth, love, and home. His movies however, would, not be what they are today without the partnership he formed early in his career with Mamoru Fujisawa a music composer who goes by the professional name of Joe Hisaishi. Their partnership formed while Hayao Miyazaki was searching for a composer to score his second animated feature film Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). Hi- saishi had an impressive resume having graduated from Kunitachi College of Music, in addition to studying directly under the famous film composer Masaru Sato who is known for the music in Seven Samurai and early Godzilla films. Hisaishi’s second album, titled Information caught the attention of Miyazaki, and Hisaishi was hired to score Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984). With its huge success consequently every other prom- inent movie of Miyazaki’s since. (Koizumi, Kyoko. 2010) Hisaishi’s minimalistic yet evocative melodies paired with Miyazaki’s creative im- agery and stories proved to be an incredible partnership and many films of theirs have been critically acclaimed, such as Princess Mononoke (1997), which was the first ani- mated film to win Picture of the Year at the Japanese Academy Awards; or Spirited Away (2001), which was the first anime film to win an American Academy Award. -

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: a Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: A Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 25–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 01:01 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 25 Chapter 1 P RINCESS MONONOKE : A GAME CHANGER Shiro Yoshioka If we were to do an overview of the life and works of Hayao Miyazaki, there would be several decisive moments where his agenda for fi lmmaking changed signifi cantly, along with how his fi lms and himself have been treated by the general public and critics in Japan. Among these, Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) and the period leading up to it from the early 1990s, as I argue in this chapter, had a great impact on the rest of Miyazaki’s career. In the fi rst section of this chapter, I discuss how Miyazaki grew sceptical about the style of his fi lmmaking as a result of cataclysmic changes in the political and social situation both in and outside Japan; in essence, he questioned his production of entertainment fi lms featuring adventures with (pseudo- )European settings, and began to look for something more ‘substantial’. Th e result was a grave and complex story about civilization set in medieval Japan, which was based on aca- demic discourses on Japanese history, culture and identity. -

Spirited Away Study Guide.Pdf

ISSUE 29 AUSTRALIAN SCREEN EDUCATION 1 STUDY GUIDE VYVYAN STRANIERI AND CHRISTINE EVELY CHRISTINE AND STRANIERI VYVYAN A Film by Hayao Miyazaki Spirited Away his study guide to accompany the Japanese anime Spirited Away, has been written for stu- Spirited Away has a of viewers, their previous experiences, especially with anima and manga, and their beliefs and values. BEFORE VIEWING THE FILM ABOUT THE FILM Chihiro is a wilful, headstrong girl who thinks everyone should fi t in with her ideas and meet her needs. When her parents Akio and Yugo tell her they are moving house, Chihiro is furious. As they leave, she clings to the traces of her old life. Arriving at the end of a mysterious cul-de-sac, the family is confronted by a large red building with an endless gaping tunnel that looks very much like a gigantic mouth. Reluctantly Chihiro follows her parents into the tunnel. The family discover a ghostly town and come across a sumptuous banquet. Akio and Yugo begin eating more and more greedily. Before Chihiro’s eyes her parents are transformed into pigs! Unknowingly they have strayed into a world inhabited by ancient gods and magical beings, ruled over by Yubaba, a AUSTRALIAN SCREEN EDUCATION ISSUE 29 2 music posters books Film Title television trailers toys CONCEPT MAP demonic sorceress. Yubaba tells Chihiro map) showing how people came to that newcomers are turned into animals know about the fi lm. before being killed and eaten. Luckily • How did you fi nd out about Spirited for Chihiro she mets Haku who tells her Away? Make a list of things you had that she can escape this fate by mak- heard about Spirited Away before ing herself useful. -

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented In

Elements of Realism in Japanese Animation Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By George Andrew Stey Graduate Program in East Asian Studies The Ohio State University 2009 Thesis Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance, Advisor Professor Maureen Hildegarde Donovan Professor Philip C. Brown Copyright by George Andrew Stey 2009 Abstract Certain works of Japanese animation appear to strive to approach reality, showing elements of realism in the visuals as well as the narrative, yet theories of film realism have not often been applied to animation. The goal of this thesis is to systematically isolate the various elements of realism in Japanese animation. This is pursued by focusing on the effect that film produces on the viewer and employing Roland Barthes‟ theory of the reality effect, which gives the viewer the sense of mimicking the surface appearance of the world, and Michel Foucault‟s theory of the truth effect, which is produced when filmic representations agree with the viewer‟s conception of the real world. Three directors‟ works are analyzed using this methodology: Kon Satoshi, Oshii Mamoru, and Miyazaki Hayao. It is argued based on the analysis of these directors‟ works in this study that reality effects arise in the visuals of films, and truth effects emerge from the narratives. Furthermore, the results show detailed settings to be a reality effect common to all the directors, and the portrayal of real-world problems and issues to be a truth effect shared among all. As such, the results suggest that these are common elements of realism found in the art of Japanese animation. -

Spirited Away (Miyazaki, Japan, 2001)

GCSE Film Studies - Focus Film Factsheet Spirited Away (Miyazaki, Japan, 2001) Component 2: Global Film; Narrative, • The initial dress codes are gender neutral Representation & Film Style and western in nature, contrasting with the Focus Area: Representation traditional Japanese clothes worn in the spirit world by Chihiro, Haku and others. Once Chihiro leaves the Bathhouse (for the train PART 1: Key Sequence(s) and ride was Miyazaki’s original ending; the timings and/or links remaining aiding the film’s coda) she removes Sequence 1 - ‘Opening Sequence’ 0:00 – 00:06:10 her Bathhouse uniform and returns to her original, androgynous and Western clothing. Sequence 2 – Chihiro meets Haku/ enters the spirit world 00:10:48-00:15:11 • The buildings were designed to evoke nostalgia in the viewers and seems like a Sequence 3 – Chihiro meets Kamaji / enters parody of the past (linking to her father’s the Boiler Room 00:21:55 – 00:24:30 comments about it being a ‘theme park’). Sequence 4 – Chihiro at Zeniba’s house • Red lighting throughout the newly emerged spirit with No Face 01:45:52 – 01:48:08 world in sequence 2, signifying the danger. Editing PART 2: STARTING POINTS - Key Elements • Slow pace to establish characters, of Film Form (Micro Features) narrative and setting. Cinematography (including Lighting) • Continuity editing used to support the • High angle mid shot (MS) of Chihiro in audience’s understanding narrative and the the back of the car denoting her place strange world that the spirits inhabit. within the family as a child/female. • In contrast to the more familiar low-budget • Camera movement changes as they enter anime Miyazaki kept a higher frame rate (30fps) the forest reflecting the importance of the as opposed to the more commonly used 24fps. -

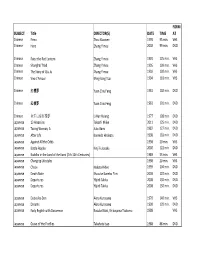

Language Lab Video Catalog

FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Chinese Ermo Zhou Xiaowen 1995 95 min. VHS Chinese Hero Zhang Yimou 2002 99 min. DVD Chinese Raise the Red Lantern Zhang Yimou 1991 125 min. VHS Chinese Shanghai Triad Zhang Yimou 1995 109 min. VHS Chinese The Story of Qiu Ju Zhang Yimou 1992 100 min. VHS Chinese Vive L'Amour Ming‐liang Tsai 1994 118 min. VHS Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 102 min. DVD Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 101 min. DVD Chinese 金玉良緣紅樓夢 Li Han Hsiang 1977 108 min. DVD Japanese 13 Assassins Takashi Miike 2011 125 min. DVD Japanese Taxing Woman, AJuzo Itami 1987 127 min. DVD Japanese After Life Koreeda Hirokazu 1998 118 min. DVD Japanese Against All the Odds 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Battle Royale Kinji Fukasaku 2000 122 min. DVD Japanese Buddha in the Land of the Kami (7th‐12th Centuries) 1989 53 min. VHS Japanese Changing Lifestyles 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Chaos Nakata Hideo 1999 104 min. DVD Japanese Death Note Shusuke Kaneko Film 2003 120 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Dodes'ka‐Den Akira Kurosawa 1970 140 min. VHS Japanese Dreams Akira Kurosawa 1990 120 min. DVD Japanese Early English with Doraemon Kusuba Kôzô, Shibayama Tsutomu 1988 VHS Japanese Grave of the Fireflies Takahata Isao 1988 88 min. DVD FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Japanese Happiness of the Katakuris Takashi Miike 2001 113 min. DVD Japanese Ikiru Akira Kurosawa 1952 143 min. -

From Ashes to Stone: Development of Chihiro in “Spirited Away” "You're

Spirited Away 1 From Ashes to Stone: Development of Chihiro in “Spirited Away” "You're called Chihiro? That name is too long and hard to pronounce From now on, you’ll be called Sen. You got that? You're Sen." - Yu-Baaba An insecure little girl is thrown in a world of wonders, magical and dangerous at the same time, and emerges a strong, assertive character. Chihiro is able to accomplish this because she does not lose her own identity to the name-stealer Yu-Baaba – and in turn does not lose her virtues. Her personal journey becomes even more valiant when compared to the other characters of the bathhouse, who have lost their soul with their name. The newest installment in Studio Ghibli’s unparalleled collection of animation movies, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (Spirited Away, “Sen or Chihiro in the Land of the Gods”) accomplishes everything its predecessors did – seamless animation, an engaging story, and a brilliant soundtrack. Spirited Away is a story about a girl who is stuck in a mythical world of gods, ghosts, and witches – Chihiro must overcome adversity and fear in order to save her parents and escape the world that has enslaved her. Director Miyazaki Hayao, head of Studio Ghibli, has managed to craft a cinematic masterpiece, one that will doubtless be considered a classic. Spirited Away takes on an extra level of significance, as Miyazaki has announced that it will be his last film. In retrospect, it can be seen that Spirited Away has amalgamated the best elements of previous Ghibli-Miyazaki movies into one spectacular film about a lost little girl named Chihiro. -

Analysis on the Culture Concepts in the Movie Spirited Away Bocong Sun1,A

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 466 Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Seminar on Education, Management and Social Sciences (ISEMSS 2020) Analysis on the Culture Concepts in the Movie Spirited Away Bocong Sun1,a BFA Producing, New York Film Academy, Burbank, CA 91505, USA Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT In recent years, Japanese animation movies have become popular in the world. Because of all of those classic and amazing animations, Japan has become one of the major countries that has a strong cultural industry. After decades of development, Japanese animation industry has gradually formed its own unique style. Japan gradually opens the foreign market by its animation movies. Hayao Miyazaki is a famous Japanese animation director, and his projects cannot be replaced in the global animation industry. Since the establishment of studio Ghibli in 1985, it has collaborated with Hayao Miyazaki and made many excellent animation movies, especially Spirited Away. This movie is one of the most popular animations in the world that received many positive reviews and sold well. Also, this movie became the peak in the history of Japanese animation. Spirited Away contains rich Japanese elements and a unique social background, so it not only attracts Japanese audience, but also other countries' audience who are interested in Japanese culture. The detail and elements make audience get a spiritual resonance in an acceptable way. This paper makes a detailed analysis about the relationship between culture and metaphors in this movie. Keywords: Story Plot, semiotics, ideology critique, psychological analysis, feminism. -

(XXXV:12) Hayao Miyazaki the WIND RISES (2014), 126 Min

November 14, 2017 (XXXV:12) Hayao Miyazaki THE WIND RISES (2014), 126 min. (The online version of this handout has color images and hot urls.) ACADEMY AWARDS, 2014 Nominated for Best Animated Feature DIRECTED BY Hayao Miyazaki WRITTEN BY Hayao Miyazaki (comic & screenplay) PRODUCED BY Naoya Fujimaki, Ryoichi Fukuyama, Kôji Hoshino, Nobuo Kawakami, Robyn Klein, Frank Marshall, Seiji Okuda, Toshio Suzuki, Geoffrey Wexler MUSIC Joe Hisaishi CINEMATOGRAPHY Atsushi Okui FILM EDITING Takeshi Seyama ART DIRECTION Yôji Takeshige SOUND DEPARTMENT Howard Karp (dialogue editor), Koji Kasamatsu (sound engineer) Eriko Kimura (adr director), Scott Levine, Michael Miller, Cheryl Nardi, Renee Russo, Brad Semenoff, Matthew Wood Stanley Tucci…Caproni ANIMATION DEPARTMENT Hiroyuki Aoyama, Masaaki Endou, Mandy Patinkin…Hattori Taichi Furumata, Shôgo Furuya, Makiko Futaki, Hideki Hamazu, Mae Whitman…Kayo Horikoshi / Kinu Shunsuke Hirota, Takeshi Honda, Kazuki Hoshino, Fumie Imai, Werner Herzog…Castorp Takeshi Imamura, Yoshimi Itazu, Megumi Kagawa, Katsuya Jennifer Grey…Mrs. Kurokawa Kondô, Tsutomu Kurita, Kitarô Kôsaka William H. Macy…Satomi Hiroko Minowa Zach Callison…Young Jirô Madeleine Yen…Young Nahoko CAST (all cast are voice only) Eva Bella…Young Kayo Hideaki Anno…Jirô Horikoshi Edie Mirman…Jirô's Mother Hidetoshi Nishijima…Honjô Darren Criss…Katayama Miori Takimoto…Naoko Satomi Elijah Wood…Sone Masahiko Nishimura…Kurokawa Ronan Farrow…Mitsubishi Employee Mansai Nomura ...Giovanni Battista Caproni David Cowgill…Flight Engineer Jun Kunimura…Hattori Mirai Shida…Kayo Horikoshi HAYAO MIYAZAKI (b. January 5, 1941 in Tokyo, Japan) grew up Shinobu Ohtake ...Kurokawa's Wife surrounded by planes. His father was the director of Miyazaki Morio Kazama…Satomi Airplane, a manufacturing concern that built parts for Zero Keiko Takeshita…Jirô's Mother fighter planes. -

Popular Culture

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ POPULAR CULTURE A wide spectrum of popular tastes Manga With the appearance of writer-illustrator Tezuka Osamu after World War II, so-called “story manga,” or illustrated publications in comic book format, developed in a somewhat unique way in Japan. At one time, the main readers of such publications were people born during the “baby boom” of 1947–1949, but as those readers grew older, many different types of manga came into being. Beginning in the 1960s, manga readership steadily expanded to include everyone from the very young to people in their thirties and forties. As of 2016, manga accounted for 33.8% of the volume of all books and magazines sold in Japan, with their influence being felt in various art forms and the culture at large. Though some story manga are aimed at small children who are just beginning to learn to read, others are geared toward somewhat older boys and/or girls, as well as a general Manga comics readership. There are gag manga, which Manga magazines on sale in a store. (Photo courtesy of Getty Images) specialize in jokes or humorous situations, and experimental manga, in the sense that they pursue innovative types of expression. Some are nonfictional, treating information of weekly circulation of over 6 million and different sorts, either of immediate practical affiliated marketing systems for animation and use or of a historical, even documentary, video games. Most typically, children’s manga nature. stories feature young characters and depict The appearance in 1959 of the two their growth as they fight against their weekly children’s manga magazines, Shonen enemies and build friendships with their Magazine and Shonen Sunday, served to companions.