One Is Not Born Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Masculinity in Selected Shakespearean and Nigerian Plays

FEMALE MASCULINITY IN SELECTED SHAKESPEAREAN AND NIGERIAN PLAYS BY OLANREWAJU, FELICIA TITILAYO MATRICULATION NUMBER: 64869 B.A English/Educ. (Ilorin), MLS, M.A. English (Ibadan) A Thesis in the Department of English, Submitted to the Faculty of Arts In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN, IBADAN AUGUST, 2014. CERTIFICATION I certify that this work was carried out by Olanrewaju Felicia Tiitlayo in the Department of English, University of Ibadan. __________________ _____________ Supervisor Date Prof. Nelson O.Fashina. Department of English, University of Ibadan, Ibadan. ii DEDICATION This PhD thesis, which is made possible through the inspiration of God almighty, is dedicated to all fathers who believe and labour for the highest education of the girl-child. This is especially dedicated to my father, Chief Julius, O. Ajonibode, who gave me the courage most fathers of yesteryears never cherished and for having an implicit trust of her darling daughter. This is also dedicated to all husbands that support their wives in the course of educational pursuits, particularly the PhD. studies; and husbands who believe in women as the pillars of good homes and foundation of a better nation. This is moreover dedicated to my husband, Rev. Adewale Olanrewaju… for being my pillar of strength and faith during the programme. And for all the boys that stand by their mothers to achieve success. The thesis is also dedicated to you, Aduragbemi. May God never cease to keep you under His wings. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My profound gratitude goes to Almighty God, the Omniscient and Omnipotent, who directs my footsteps on the path of knowledge, for the gift of life, divine mercy and kindness. -

Lokaverkefni Til MA-Prófs Í Almennri Bókmenntafræði Verkfæri Húsbóndans

Lokaverkefni til MA-prófs í almennri bókmenntafræði Verkfæri húsbóndans Birtingamyndir hins hvíta valdakerfis í sjónvarpsþáttaröðinni Dear White People Sjöfn Hauksdóttir Leiðbeinandi: Alda Björk Valdimarsdóttir Júní 2020 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Almenn bókmenntafræði Verkfæri Húsbóndans Birtingamyndir hins hvíta valdakerfis í sjónvarpsþáttaröðinni Dear White People Ritgerð til M.A.-prófs Sjöfn Hauksdóttir Kt.: 120291-3869 Leiðbeinandi: Alda Björk Valdimarsdóttir Mars 2020 Útdráttur Saga Bandaríkjanna er flókin og margslunginn, en eitt sem gengur í gegnum hana eins og rauður þráður, frá tímum stofnfeðra hennar og til okkar daga eru kynþáttafordómar og samfélagsleg kúgun sem heldur svörtum niðri. Oft gleymist að líta á alla heildina þegar staða svartra í dag er skoðuð, og á þá ótalmörgu þræði kúgunnar sem vefa sér leið inn í flestallt í samfélaginu, frá formlegum stofnunum, til gamalla gilda, til menningar og fegurðardýrkunar sem og fjölskyldugerða. Hið hvíta valdakerfi er samofið net þátta sem stuðlar að kúgun kvenna og jaðarsettra hópa. Hugtakið getur virst yfirgripsmikið en í sjónvarpsþáttaröðinni Dear White People spilar það stórann þátt í framvindunni. Persónur þáttarins eru ungt, svart fólk sem tekst á við lífið innan hins hvíta valdakerfis. Ýmsar aukajaðarsetningar spila inn í sem vert er að skoða, og verður litið til hörundlsitafordóma, póstrasisma og póstfemínisma innan þáttanna. Sjónum verður beint að tveimur aðalpersónum þáttanna, þeim Sam og Coco, og stöðu þeirra sem ungra, svartra kvenna í samfélaginu. Einnig verður litið á aukapersónur þáttanna og hvernig aðrir þættir hins hvíta valdakerfis hafa áhrif á þær. Auk fræðilegrar samantektar og hugtakaskýringa verður litið til bandarískrar menningarsögu, sem spilar stóran þátt í ástandinu eins og það er í dag og hvernig það speglast í þáttunum. -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un vers ty of W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 25, Number 2 Summer 2005 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents Volume 25, Number 2 (Summer 2005) Periodical literature is the cutting edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum offeminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from currentissues ofmajor feministjournals are reproduced in each issue ofFeminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the fOllowing information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. sUbscription price(s). 4. Subscription address. 5. Current editor. 6. -

Object Relations, Buddhism, and Relationality in Womanist Practical Theology (Black Religion/Womanist Thought/Social Justice) Jul 28, 2018 by Pamela Ayo Yetunde

Emergent Themes in Critical Race and Gender Research A Thousand Points of Praxis and Transformation Stephanie Y. Evans | © 2019* | https://bwstbooklist.net/ THEMATIC LIST Updated February 27, 2019 The Black Women’s Studies Booklist is a web resource that contributes to the growth, development, and institutionalization of Black women’s studies (BWST). By collecting over 1,400 book publications and organizing them thematically, this comprehensive bibliography clarifies past, present, and forthcoming areas of research in a dynamic field. The BWST Booklist is useful as a guide for research citation, course instruction, and advising for undergraduate/graduate projects, theses, dissertations, and exams. *APA Citation: Evans, S. Y. (February 16, 2019). The Black Women's Studies Booklist: Emergent Themes in Critical Race and Gender Research. Retrieved from https://bwstbooklist.net/ BWST Booklist 2019 © S. Y. Evans | page 1 Praxis, a Greek word, refers to the application of ideas. The West African Adinkra concept, Sesa Wo Suban, symbolizes change and the transformation of one’s life. These two concepts, praxis and transformation, summarize the overarching message of Black women’s studies. This thematic booklist traces histories and trends of scholarly work about race and gender, revealing patterns of scholarship that facilitate critical analysis for individual, social, and global transformation. The year 2019 represents an opportune time to reflect on Black women’s studies. In the past three years, several major developments have signaled the advancement of BWST as an academic area of inquiry. These developments offer an opportunity to reassess the state of the field and make clear the parameters, terrain, and contours of the world of BWST. -

Kitossa Brock University

Southern Journal of Canadian Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1-2 (December 2012), 255-284 Black Canadian Studies and the Resurgence of the Insurgent African Canadian Intelligentsia1 Tamari Kitossa Brock University Dr. Tamari Kitossa, Department of Sociology, Brock University [email protected] Abstract: This essay seeks to account for the appellaon, factors and forces implicated in the nascent ar?culaon of Black Canadian Studies. I suggest that the emergence of Black Canadian Studies is a dialogic interplay of the African Canadian intelligentsia and community’s proac?on toward appreciang the agency of African Canadians, and, a reac?on to racist epistemology and research that objec?fies them. I seek to account for this dialogue as a progression of the earlier development of African and Caribbean Studies by the African Canadian intellectuals. I speculate on what the field of Black Canadian Studies might look like, challenges it may encounter and propose steps for how its development might proceed. In doing so, I draw lessons primarily from African American Studies, but also Women’s Studies. Introduc;on be included) by this insurgent appellation and also as a bona fide As a practical matter, the study of emerging area of study. Toward a Black Canada is an established fact, but sociological analysis of the forces at it is not a contradiction to say it is not play, for further consideration are the yet an officially designated area of study. following: What is in a name – Black This could easily be an essay on the Canadian Studies – and what are its sociology of knowledge, on how characteristics – Pan-Africanism, disciplines or fields of study come to be Africentrism, Diasporic Studies? constituted and legitimated in the Compared to the 40-year time-line for academy by processes of political action. -

4 “Caribbean Canadian Feminism and Decolonial Practice in Makeda

Caribbean Canadian Feminism and Decolonial Practice in Makeda Silvera’s The Heart Does Not Bend and Her Head A Village Wiebke Beushausen Abstract: This article explores the fictional and non-fictional work of Jamaican-Canadian writer and activist Makeda Silvera (*1955) in terms of its significance for CariBBean- Canadian women’s writing and Black feminism in Canada. It investigates its potential to challenge dominant discourses that, to varying degrees, have a colonial continuity Both in the CariBBean and Canadian contexts. These discourses pertain to issues of racism and heteronormativity intertwined with citizenship, migration laws or an exclusionary historiography. The narrative perspectives and stereotypical representations of masculinity in The Heart Does Not Bend as well as the short stories “BaBy” and “Her Head a Village” privilege women’s voices, lesbian erotic agency and Black female emBodiment. “Recognizing the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama.”1 Introduction This article explores the fictional and non-fictional work of Jamaican-Canadian writer and activist Makeda Silvera in terms of its significance for CaribBean women’s writing and Black feminism in Canada. It investigates its potential to challenge dominant discourses, which, in varying degrees, have a colonial origin both in the Caribbean 75 | Caribbean Canadian Feminism and Decolonial Practice and Canadian context. These discourses pertain to issues of racism, to a heterosexuality intertwined with national identity, cultural politics and citizenship, as well as migration laws, historiography and white Canadian liberal feminism. -

Compilation of Comprehensive Reading Lists Graduate Program in Sociology York University June 2006 Edition

Compilation of Comprehensive Reading Lists Graduate Program in Sociology York University June 2006 edition TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Contributors 3 Programme Manual Directions for Preparing a Reading List 3 Culture and Identities Cultural Studies 4 “Race” and Racism 6 Sex and Gender Systems 8 Social Psychology 11 Sociology of the City / Urban Sociology Still to come Global Sociology Citizenship Studies 13 Diaspora Studies 17 International Migration, Transnationalism, and Refugee Studies 20 Latin American and Caribbean Studies 25 Social Movements 29 Sociology of Development 32 Nature / Society / Culture Critical Sexualities 34 Environmental Sociology 37 Social Studies of Science 40 Social Studies of Technology 43 Sociology of the Life Course 46 Processes, Practices & Power Class & Structural Inequalities / Stratification 49 Criminology, Corrections and Criminalization 51 Economic Sociology 53 Health Studies 55 Historical Sociology and Social History 59 Law and Justice 61 Political Sociology 63 Social Regulation 66 Sociology of Education 68 Sociology of Work and Labour 71 Critical Social Theory Classical Theory 73 Contemporary Social Theory 75 Feminist Theory 79 Marxist Theory 86 Postcolonial Theory Still to come Social Research Methods Historical and Archival Methods 88 Qualitative Methods 90 Survey Research 92 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS Gamal Abdel-Shehid (Convenor) • Aliya Amarshi (Graduate Ass’t) • Anne-Marie Ambert • Paul Anisef Elizabeth Asante • Peter Baehr (Lingnan U.) • Himani Bannerji • Barbara Beardwood • Margaret Beare • Jody Berland Greg Bird (Graduate Ass’t) • Kathy Bischoping (Organizer, Convenor) • Susan Braedley • Debi Brock (Convenor for two lists) Eduardo Canel (York U. Social Science) • Don Carveth (Convenor) • Sheila Cavanagh • Beatriz Cid • Nancy Clark Karine Côté-Boucher • Gordon Darroch • Tania Das Gupta • Shane Doheny (U. -

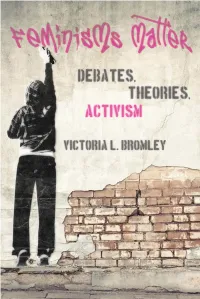

Feminisms Matter This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Feminisms Matter This page intentionally left blank Copyright © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2012 Higher Education Division www.utppublishing.com All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisher—or in the case of photocopying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5—is an infringement of the copyright law. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Victoria L., 1959– Feminisms matter : debates, theories, activism / Victoria L. Bromley. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-0500-8 1. Feminism. 2. Anti-feminism. 3. Feminist theory. 4. Women political activists. I. Title. HQ1154.B85 2012 305.42 C2012-905269-8 We welcome comments and suggestions regarding any aspect of our publications— please feel free to contact us at [email protected] or visit our Internet site at www.utppublishing.com. North America UK, Ireland, and continental Europe 5201 Dufferin Street NBN International North York, Ontario Estover Road, Plymouth, PL6 7PY, UK Canada, M3H 5T8 ordErS PHoNE: 44 (0) 1752 202301 ordErS fax: 44 (0) 1752 202333 2250 Military Road ordErS E-MaIL: [email protected] Tonawanda, New York USA, 14150 ordErS PHoNE: 1-800-565-9523 ordErS fax: 1-800-221-9985 ordErS E-MaIL: [email protected] Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders; in the event of an error or omission, please notify the publisher. -

Canada and Its Discontents

98 Canadian Literature A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Autumn 200 8 $19 Ca n a d ian 98 Literature canada and its discontents and its canada Canada and Its Discontents Canadian Literature / Littérature canadienne A Quarterly of Criticism and Review Number 198, Autumn 2008, Canada and Its Discontents Published by The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Editor: Margery Fee Associate Editors: Laura Moss (Reviews), Glenn Deer (Acting Editor), Larissa Lai (Poetry), Réjean Beaudoin (Francophone Writing), Judy Brown (Reviews) Past Editors: George Woodcock (1959–1977), W.H. New (1977–1995), Eva-Marie Kröller (1995–2003), Laurie Ricou (2003–2007) Editorial Board Heinz Antor Universität Köln Janice Fiamengo University of Ottawa Carole Gerson Simon Fraser University Coral Ann Howells University of Reading Smaro Kamboureli University of Guelph Jon Kertzer University of Calgary Ric Knowles University of Guelph Neil ten Kortenaar University of Toronto Louise Ladouceur University of Alberta Patricia Merivale University of British Columbia Judit Molnár University of Debrecen Maureen Moynagh St. Francis Xavier University Ian Rae McGill University Roxanne Rimstead Université de Sherbrooke Patricia Smart Carleton University David Staines University of Ottawa David Williams University of Manitoba Mark Williams Victoria University, New Zealand Editorial Glenn Deer Canada and Its Discontents 6 Articles Brian Johnson Simulacra and Stimulations: Cocksure, Postmodernism, and Richler’s Phallic Hero 12 Stephen Dunning What Would Sam Waters Do? Guy Vanderhaeghe -

Feminisms and Womanisms a Women's Studies Reader

Canadian Scholars 425 Adelaide Street West, Suite 200 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5V 3C1 Phone: 416-929-2774 Fax: 416-929-1926 Email: [email protected] Feminisms and Womanisms A Women's Studies Reader _Feminisms and Womanisms_ brings together theory and practical application, so that feminist discourse interacts as a partner with the lived experience of women's social action. The selections combine classics in feminist thought with work from modern theorists and offer a solid foundation in international feminism. The conceptual understanding embedded in the terms feminism and womanism contributes to feminist discourse, a carefully differentiated focus on the ideological uses of language to define relationships that have been historically mired in domination. The terms also define the way gender often has been used to signify and support domination. Given that feminism and womanism are interpretive concepts, there is always a sense that knowledge-making is in progress; for there is nothing static or stagnant about feminism, feminist theory and feminist action. The formative nature of the feminist movement has, of necessity, a parallel interpretive theory. This reader embraces both the formative nature of the movement and the accompanying interpretive theories. It also pays attention to the chronological, cultural, geopolitical, racial and ethnic landscapes and sites where women live, carry out social action and theorize issues of equality. For both the general and academic reader, this book will be edifying while providing exposure to the feminist, womanist voices that inform the scholarship. Author Information Althea Prince **Dr. Althea Prince** has taught at York University and the University of Toronto. She is also a fiction writer and essayist.