Thehimalayannaturalist Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Deacon As Wise Fool: a Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate

ATR/100.4 The Deacon as Wise Fool: A Pastoral Persona for the Diaconate Kevin J. McGrane* Deacons often sit with the hurt and marginalized. It is in keeping with our ordination vows as deacons in the Episcopal Church, which say, “God now calls you to a special ministry of servanthood. You are to serve all people, particularly the poor, the weak, the sick, and the lonely.”1 Ever task focused, deacons look for the tangible and concrete things we can do to respond to the needs of the least of Jesus’ broth- ers and sisters (Matt. 25:40). But once the food is served, the money given, the medicine dispensed, then what? The material needs are supplied, but the hurt and the trauma are still very much present. What kind of pastoral care can deacons bring that will respond to the needs of the hurting and traumatized? I suggest that, if we as deacons are going to be sources of contin- ued pastoral care beyond being simple providers of material needs, we need to look to the pastoral model of the wise fool for guidance. With some exceptions here and there, deacons are uniquely fit to practice the pastoral persona of the wise fool. The wise fool is a clinical pastoral persona most identified and de- veloped by the pastoral theologians Alastair V. Campbell and Donald Capps. The fool is an archetype in human culture that both Campbell and Capps view as someone capable of rendering pastoral care. In his essay “The Wise Fool,”2 Campbell describes the fool as a “necessary figure” to counterpoint human arrogance, pomposity, and despo- tism: “His unruly behavior questions the limits of order; his ‘crazy’ outspoken talk probes the meaning of ‘common sense’; his uncon- ventional appearance exposes the pride and vanity of those around * Kevin J. -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Taiwan 2020 Feb 1, 2020 to Feb 12, 2020 Phil Gregory & local guide Arco Huang For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. This gorgeous male Swinhoe's Pheasant was one of the birds of the trip! We found a pair of these lovely endemic pheasants at Dasyueshan. Photo by guide Phil Gregory. This was a first run for the newly reactivated Taiwan tour (which we last ran in 2006), with a new local organizer who proved very good and enthusiastic, and knew the best local sites to visit. The weather was remarkably kind to us and we had no significant daytime rain, somewhat to my surprise, whilst temperatures were pretty reasonable even in the mountains- though it was cold at night at Dasyueshan where the unheated hotel was a bit of a shock, but in a great birding spot, so overall it was bearable. Fog on the heights of Hohuanshan was a shame but at least the mid and lower levels stayed clear. Otherwise the lowland sites were all good despite it being very windy at Hengchun in the far south. Arco and I decided to use a varied assortment of local eating places with primarily local menus, and much to my amazement I found myself enjoying noodle dishes. The food was a highlight in fact, as it was varied, often delicious and best of all served quickly whilst being both hot and fresh. A nice adjunct to the trip, and avoided losing lots of time with elaborate meals. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Thailand Highlights 14Th to 26Th November 2019 (13 Days)

Thailand Highlights 14th to 26th November 2019 (13 days) Trip Report Siamese Fireback by Forrest Rowland Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Forrest Rowland Trip Report – RBL Thailand - Highlights 2019 2 Tour Summary Thailand has been known as a top tourist destination for quite some time. Foreigners and Ex-pats flock there for the beautiful scenery, great infrastructure, and delicious cuisine among other cultural aspects. For birders, it has recently caught up to big names like Borneo and Malaysia, in terms of respect for the avian delights it holds for visitors. Our twelve-day Highlights Tour to Thailand set out to sample a bit of the best of every major habitat type in the country, with a slight focus on the lush montane forests that hold most of the country’s specialty bird species. The tour began in Bangkok, a bustling metropolis of winding narrow roads, flyovers, towering apartment buildings, and seemingly endless people. Despite the density and throng of humanity, many of the participants on the tour were able to enjoy a Crested Goshawk flight by Forrest Rowland lovely day’s visit to the Grand Palace and historic center of Bangkok, including a fun boat ride passing by several temples. A few early arrivals also had time to bird some of the urban park settings, even picking up a species or two we did not see on the Main Tour. For most, the tour began in earnest on November 15th, with our day tour of the salt pans, mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves of the famed Pak Thale Shore bird Project, and Laem Phak Bia mangroves. -

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1

United States Department of Agriculture Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptation in the Intermountain Region Part 1 Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-375 April 2018 Halofsky, Jessica E.; Peterson, David L.; Ho, Joanne J.; Little, Natalie, J.; Joyce, Linda A., eds. 2018. Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the Intermountain Region. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-375. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Part 1. pp. 1–197. Abstract The Intermountain Adaptation Partnership (IAP) identified climate change issues relevant to resource management on Federal lands in Nevada, Utah, southern Idaho, eastern California, and western Wyoming, and developed solutions intended to minimize negative effects of climate change and facilitate transition of diverse ecosystems to a warmer climate. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service scientists, Federal resource managers, and stakeholders collaborated over a 2-year period to conduct a state-of-science climate change vulnerability assessment and develop adaptation options for Federal lands. The vulnerability assessment emphasized key resource areas— water, fisheries, vegetation and disturbance, wildlife, recreation, infrastructure, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services—regarded as the most important for ecosystems and human communities. The earliest and most profound effects of climate change are expected for water resources, the result of declining snowpacks causing higher peak winter -

© 生物多样性biodiversity Science

生物多样性 2019, 27 (1): 76–80 doi: 10.17520/biods.2018273 Biodiversity Science http://www.biodiversity-science.net •生物编目• 钱江源国家公园体制试点区鸟类多样性与区系组成 1 1 2 3 4* 钱海源 余建平 申小莉 丁 平 李 晟 1 (钱江源国家公园生态资源保护中心, 浙江开化 324300) 2 (中国科学院植物研究所植被与环境变化国家重点实验室, 北京 100093) 3 (浙江大学生命科学学院, 杭州 310058) 4 (北京大学生命科学学院, 北京 100871) 摘要: 生物多样性编目是自然保护地有效管理与政策制定的基础。本研究收集整理了钱江源国家公园体制试点区 (简称钱江源国家公园)内的鸟类记录, 数据来源包括专项鸟类调查、红外相机调查、自动录音调查、公众科学活 动4大类。共记录到分属17目64科的252种鸟类。其中, 国家I级重点保护鸟类2种, 为白颈长尾雉(Syrmaticus ellioti) 和白鹤(Grus leucogeranus), 国家II级重点保护鸟类34种; 在IUCN物种红色名录和中国脊椎动物红色名录中被评 估为受威胁(即极危、濒危、易危和近危)的分别有10种和34种: 共计有46种鸟类为需受重点关注的物种, 占总物种 数的18.25%。记录到4种浙江省鸟类新记录, 分别为黄嘴角鸮(Otus spilocephalus)、方尾鹟(Culicicapa ceylonensis)、 远东苇莺(Acrocephalus tangorum)和蓝短翅鸫(Brachypteryx montana)。钱江源国家公园内鸟类组成兼具古北界和东 洋界成分, 东洋种(45.24%)占比略高于古北种(42.46%); 留鸟和迁徙性鸟类的物种数近似; 繁殖鸟类中以东洋种为 主(68.79%), 冬候鸟中则以古北种占绝对优势(94.83%)。本研究结果表明, 钱江源国家公园虽然面积有限(252 km2), 但记录鸟种数占浙江全省的52%, 在鸟类多样性保护中有重要价值; 同时本研究的结果将为该国家公园管理以及 未来的鸟类监测和研究提供基础本底。 生物编目 关键词: 钱江源国家公园; 鸟类监测; 生物多样性编目; 本底调查 Diversity and composition of birds in the Qianjiangyuan National Park pilot Haiyuan Qian1, Jianping Yu1, Xiaoli Shen2, Ping Ding3, Sheng Li4* 1 Center of Ecology and Resources, Qianjiangyuan National Park, Kaihua, Zhejiang 324300 2 State Key Laboratory of Vegetation and Environmental Change, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093 3 College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058 4 School of Life Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871 Abstract: Assessments of biodiversity are the foundation to support the management and policy-making -

Class Clown and Court Jester: a Case Study Approach to the Tradition of the Fool

CLASS CLOWN AND COURT JESTER: A CASE STUDY APPROACH TO THE TRADITION OF THE FOOL By DAVID CHEVREAU B.A., York University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Counselling Psychology We accept this Thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1994 © David Chevreau, 1994 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of (jOO^fr^fr ^SfObL^y The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date Apm- ^ 1*T^ DE-6 (2/88) -ii- ABSTRACT Though he is well known, the Class Clown is not particularly well understood. With the exception of one quantitative study by Damingo and Purkey (1978), no significant research has been written on this witty character. The educational community has viewed the Class Clown by and large as an under-achieving student who, in his efforts to get attention, is a disruptive force in the classroom. As such, his behaviour, though often enormously funny, is a threat to the conformity and stability that good classroom discipline demands. -

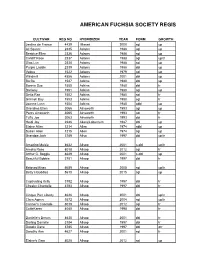

Regn Lst 1948 to 2020.Xls

AMERICAN FUCHSIA SOCIETY REGISTERED FUCHSIAS, 1948 - 2020 CULTIVAR REG NO HYBRIDIZER YEAR FORM GROWTH Jardins de France 4439 Massé 2000 sgl up All Square 2335 Adams 1988 sgl up Beatrice Ellen 2336 Adams 1988 sgl up Cardiff Rose 2337 Adams 1988 sgl up/tr Glas Lyn 2338 Adams 1988 sgl up Purple Laddie 2339 Adams 1988 dbl up Velma 1522 Adams 1979 sgl up Windmill 4556 Adams 2001 dbl up Bo Bo 1587 Adkins 1980 dbl up Bonnie Sue 1550 Adkins 1980 dbl tr Dariway 1551 Adkins 1980 sgl up Delta Rae 1552 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Grinnell Bay 1553 Adkins 1980 sgl tr Joanne Lynn 1554 Adkins 1980 sdbl up Grandma Ellen 3066 Ainsworth 1993 sgl up Percy Ainsworth 3065 Ainsworth 1993 sgl tr Tufty Joe 3063 Ainsworth 1993 dbl tr Heidi Joy 2246 Akers/Laburnum 1987 dbl up Elaine Allen 1214 Allen 1974 sdbl up Susan Allen 1215 Allen 1974 sgl up Grandpa Jack 3789 Allso 1997 dbl up/tr Amazing Maisie 4632 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up/tr Amelia Rose 8018 Allsop 2012 sgl tr Arthur C. Boggis 4629 Allsop 2001 s-dbl up Beautiful Bobbie 3781 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Beloved Brian 5689 Allsop 2005 sgl up/tr Betty’s Buddies 8610 Allsop 2015 sgl up Captivating Kelly 3782 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cheeky Chantelle 3783 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Cinque Port Liberty 4626 Allsop 2001 dbl up/tr Clara Agnes 5572 Allsop 2004 sgl up/tr Conner's Cascade 8019 Allsop 2012 sgl tr CutieKaren 4040 Allsop 1998 dbl tr Danielle’s Dream 4630 Allsop 2001 dbl tr Darling Danielle 3784 Allsop 1997 dbl tr Doodie Dane 3785 Allsop 1997 dbl gtr Dorothy Ann 4627 Allsop 2001 sgl tr Elaine's Gem 8020 Allsop 2012 sgl up Generous Jean 4813 -

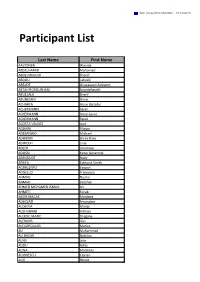

Participant List

Ref. Ares(2015)5922007 - 17/12/2015 Participant List Last Name First Name AALTONEN Wanida ABDELHAMID Mohamed ABDELMEGUID Sheref ABDOU Lahadji ABEJIDE Oluwaseun Adeyemi ABTAHIFOROUSHANI Seyedehasieh ABUELALA Sherif ABUNEMEH Omar ACHARYA Arjun Bahadur ACHERMANN Sarah ACKERMANN Anne-Laure ACKERMANN Raoul ACOSTA VALDEZ Jose ADDARII Filippo ADESANWO Michael ADHIKARI Shree Ram ADINOLFI Livia ADLER Jéromine ADOSSI Yawo Nevemde AERNOUDT Rudy AFRIFA Edmund Smith AGBALENYO Yawovi AGNELLO Francesca AHMAD Najma AHMAD Zeeshan AHMED MOHAMED ISMAIL Ali AHMETI Korab AKSIN MACAK Marijana ALBIZZATI Amandine ALCHEVA Marija ALDHUBAIBI Hitham ALEKSIC MATIC Dragana ALEXAKIS Ilias ALEXOPOULOS Marios ALI Muhammad ALI BACAR Nabilou ALIAS Jose ALIDU Adilu ALINA Marinoiu ALIONESCU Ciprian ALIX Nicole ALLET Marion ALMAZYAN Lida ALMEIDA Katia ALONSO Beatriz ALSAWALAH Abedallah ALTINOK Salih ALVARADO TANAMACHI Sayuri ALVAREZ Ana ALVES Filipe AMADIO Nicolas AMALFITANO Marie AMAZIT Anaïs AMBROSIO Giuseppe AMET Suzon AMITSIS Gabriel ANASTOPOULOS Konstantinos ANCA Gunta ANCEL Florian ANDRES Rodolphe ANDREU Tomás ANDREW Mwebaza ANDRICOPOULOU Anna ANDRIOT Patricia ANDRITSOU Anastasia ANESE Tobia ANGELOVA Milena ANNE Leautier ANSELM Cecile APOLLONI Guglielmo APOSTOLIDIS Catherine APPEL Ulrik ARNOLD David AROYAN Luciné ARREGUI Karin Arriaga Sierra Hermes ARROYO DE SANDE Carmen ARVANITI Chrysafo ASCHARI-LINCOLN Jessica ASLAN Ayse ASRAF Adeeba ASSABA Inès ATAMAN SCHARNING Ayşegül ATAYI Ayoko Veronique ATHANASIADOU Natasha Marie AUCONIE Sophie AUGER Christophe AVENTAGGIATO Giovanni -

Till Eulenspiegel As a “Recurring Character” in the Works of Hans Sachs

Narrative Arrangement in 16th-Century Till Eulenspiegel Texts: The Reinvention of Familiar Structures A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Isaac Smith Schendel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor: Dr. Anatoly Liberman June 2018 © Isaac Smith Schendel 2018 i Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Dr. Anatoly Liberman, for his kind direction, ideas, and guidance through the entire process of graduate school, from the first lectures on Middle High German grammar and Scandinavian Literature, to the preliminary exams, prospectus and multiple thesis drafts. Without his watchful eye, advice, and inexhaustible patience, this dissertation would have never seen the light of day. Drs. James A. Parente, Andrew Scheil, and Ray Wakefield also deserve thanks for their willingness to serve on the committee. Special gratitude goes to Dr. Parente for reading suggestions and leadership during the latter part of my graduate school career. His practical approach, willingness to meet with me on multiple occasions, and ability to explain the intricacies of the university system are deeply appreciated. I have also been helped by a number of scholars outside of Minnesota. The material discussed in the second chapter of the dissertation is a reformulated, expanded, and improved version of my article appearing in Daphnis 43.2. Although the central thesis is now radically different, I would still like to thank Drs. Ulrich Seelbach and Alexander Schwarz for their editorial work during that time, especially as they directed my attention to additional information and material within the S1515 chapbook. -

Project Summer Read 2020

Project SUMMER Read 2020 SUMMER READING SUGGESTIONS AND RESOURCES SUGERENCIAS DE LECTURE VERANO Y RECURSOS Elementary K-5 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read Parent Resources Recursos Para Padres Choosing Books for Children by Betsy Hearne Best of the Best for Children by Denise Perry Donavin, ed. The New Read‐Aloud Handbook by Jim Trelease For Reading Out Loud by Margaret May Kimmel Read to Me: Raising Kids Who Love to Read by Bernice E. Cullinan Parent’s Guide to the Best Books for Children by Eden Ross Lipson Reading Magic by Mem Fox Other Websites Otros sitios web White Plains Public Schools whiteplainspublicschools.org Westchester Libraries Online westchesterlibraries.org White Plains Public Library whiteplainslibrary.org White Plains Youth Bureau whiteplainsyouthbureau.org Barnes & Noble Booksellers barnesandnoble.com Common Sense Media commonsensemedia.org 2020 www.whiteplainspublicschools.org/read WHITE PLAINS PUBLIC SCHOOLS EDUCATION HOUSE FIVE HOMESIDE LANE WHITE PLAINS, NEW YORK 10605 914-422-2000 www.wpcsd.k12.ny.us Joseph L. Ricca, Ed.D. Superintendent of Schools June 2020 Dear Parent/Guardian, Many parents ask: “What can I do to help my child be a better student?” The key to a good education is reading with understanding. If you encourage your child to read, if you read to your child, if you discuss with your child what is being read, your child will develop a love for reading and learning. Reading is both fun and useful. Folktales, sports news, fashion news, business news, celebrity gossip, and comics –it all has value. Our Project Summer Read program is designed to make it easier to select books, for a full summer of reading. -

Taiwan: Formosan Endemics Set Departure Tour 17Th – 30Th April, 2016

Taiwan: Formosan Endemics Set departure tour 17th – 30th April, 2016 Tour leader: Charley Hesse Report and photos by Charley Hesse. (All photos were taken on this tour) Mikado Pheasant has become so accustomed to people at the feeding sites, it now comes within a few feet. Taiwan is the hidden jewel of Asian birding and one of the most under-rated birding destinations in the world. There are currently in impressive 25 endemics (and growing by the year), including some of the most beautiful birds in Asia, like Swinhoe’s & Mikado Pheasants and Taiwan Blue-Magpie. Again we had a clean sweep of Taiwan endemics seeing all species well, and we also found the vast majority of endemic subspecies. Some of these are surely set for species status, giving visiting birders potential ‘arm chair ticks’ for many years to come. We also saw other major targets, like Fairy Pitta, Black-faced Spoonbill and Himalayan Owl. Migrants were a little thin on the ground this year, but we still managed an impressive 189 bird species. We did particularly well on mammals this year, seeing 2 giant flying-squirrels, Formosan Serow, Formosan Rock Macaque and a surprise Chinese Ferret-Badger. We spent some time enjoying the wonderful butterflies and identified 31 species, including the spectacular Magellan Birdwing, Chinese Peacock and Paper Kite. Our trip to the island of Lanyu (Orchid Island) adds a distinct flavour to the trip with its unique culture and scenery. With some particularly delicious food, interesting history and surely some of the most welcoming people in Asia, Taiwan is an unmissable destination.