Kjartan Fløgstad's Synthesis of Local, Global, and Environmental History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications Library Faculty January 2013 The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W. Onsager Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Onsager, Lawrence W., "The Anason Family in Rogaland County, Norway and Juneau County, Wisconsin" (2013). Faculty Publications. Paper 25. http://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/library-pubs/25 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Faculty at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANASON FAMILY IN ROGALAND COUNTY, NORWAY AND JUNEAU COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS Berrien Springs, Michigan and Mauston, Wisconsin 2013 ANASON FAMILY INTRODUCTION The Anason family has its roots in Rogaland County, in western Norway. Western Norway is the area which had the greatest emigration to the United States. The County of Rogaland, formerly named Stavanger, lies at Norway’s southwestern tip, with the North Sea washing its fjords, beaches and islands. The name Rogaland means “the land of the Ryger,” an old Germanic tribe. The Ryger tribe is believed to have settled there 2,000 years ago. The meaning of the tribal name is uncertain. Rogaland was called Rygiafylke in the Viking age. The earliest known members of the Anason family came from a region of Rogaland that has since become part of Vest-Agder County. -

Hjelmeland 2021

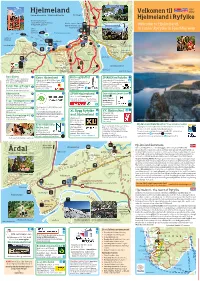

Burmavegen 2021 Hjelmeland Nordbygda Velkomen til 2022 Kommunesenter / Municipal Centre Nordbygda Leite- Hjelmeland i Ryfylke Nesvik/Sand/Gullingen runden Gamle Hjelmelandsvågen Sauda/Røldal/Odda (Trolltunga) Verdas største Jærstol Haugesund/Bergen/Oslo Welcome to Hjelmeland, Bibliotek/informasjon/ Sæbø internet & turkart 1 Ombo/ in scenic Ryfylke in Fjord Norway Verdas største Jærstol Judaberg/ 25 Bygdamuseet Stavanger Våga-V Spinneriet Hjelmelandsvågen vegen 13 Sæbøvegen Judaberg/ P Stavanger Prestøyra P Hjelmen Puntsnes Sandetorjå r 8 9 e 11 s ta 4 3 g Hagalid/ Sandebukta Vågavegen a Hagalidvegen Sandbergvika 12 r 13 d 2 Skomakarnibbå 5 s Puntsnes 10 P 7 m a r k 6 a Vormedalen/ Haga- haugen Prestagarden Litle- Krofjellet Ritlandskrateret Vormedalsvegen Nasjonal turistveg Ryfylke Breidablikk hjelmen Sæbøhedlå 14 Hjelmen 15 Klungen TuntlandsvegenT 13 P Ramsbu Steinslandsvatnet Årdal/Tau/ Skule/Idrettsplass Hjelmen Sandsåsen rundt Liarneset Preikestolen Søre Puntsnes Røgelstad Røgelstadvegen KART: ELLEN JEPSON Stavanger Apal Sideri 1 Extra Hjelmeland 7 Kniv og Gaffel 10 SMAKEN av Ryfylke 13 Sæbøvegen 35, 4130 Hjelmeland Vågavegen 2, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 916 39 619 Vågavegen 44, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 454 32 941. www.apalsideri.no [email protected] Prisbelønna sider, eplemost Tlf 51 75 30 60. www.Coop.no/Extra Tlf 938 04 183. www.smakenavryfylke.no www.knivoggaffelas.no [email protected] Alt i daglegvarer – Catering – påsmurt/ Tango Hår og Terapi 2 post-i-butikk. Grocery Restaurant - Catering lunsj – selskapsmat. - Selskap. Sharing is Caring. 4130 Hjelmeland. Tlf 905 71 332 store – post office Pop up-kafé Hairdresser, beauty & personal care Hårsveisen 3 8 SPAR Hjelmeland 11 Den originale Jærstolen 14 c Sandetorjå, 4130 Hjelmeland Tlf 51 75 04 11. -

The Norwegian Ancestry of Oscar Martin Remington; Tracing His

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Faculty Publications 2018 The orN wegian Ancestry of Oscar Martin Remington; Tracing his Roots in Roldal Parish, Hordaland County and Suldal Parish, Rogaland County, Norway and Telling the Story of his Family in Juneau County, Wisconsin Lawrence W. Onsager Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pubs Part of the Genealogy Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Onsager, Lawrence W., "The orN wegian Ancestry of Oscar Martin Remington; Tracing his Roots in Roldal Parish, Hordaland County and Suldal Parish, Rogaland County, Norway and Telling the Story of his Family in Juneau County, Wisconsin" (2018). Faculty Publications. 694. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/pubs/694 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NORWEGIAN ANCESTRY OF OSCAR MARTIN REMINGTON; TRACING HIS ROOTS IN ROLDAL PARISH, HORDALAND COUNTY AND SULDAL PARISH, ROGALAND COUNTY, NORWAY AND TELLING THE STORY OF HIS FAMILY IN JUNEAU COUNTY, WISCONSIN BY LAWRENCE W. ONSAGER THE LEMONWEIR VALLEY PRESS MAUSTON, WISCONSIN AND BERRIEN SPRINGS, MICHIGAN 2018 1 The Norwegian Ancestry of Oscar Martin Remington; Tracing His Roots in Roldal Parish, Hordaland County and Suldal Parish, Rogaland County, Norway and Telling the Story of His Family in Juneau County, Wisconsin by Lawrence Wl Onsager is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. --------------------Cataloging Data Onsager, Lawrence William, 1944- The Norwegian Ancestry of Oscar Martin Remington; Tracing His Roots in Roldal Parish, Hordaland County and Suldal Parish, Rogaland County, Norway and Telling the Story of His Family in Juneau County, Wisconsin. -

SVR Brosjyre Kart

VERNEOMRÅDA I Setesdal vesthei, Ryfylkeheiane og Frafjordheiane (SVR) E 134 / Rv 13 Røldal Odda / Hardanger Odda / Hardanger Simlebu E 134 13 Røldal Haukeliseter HORDALAND Sandvasshytta E 134 Utåker Åkra ROGALAND Øvre Sand- HORDALAND Haukeli vatnbrakka TELEMARK Vågslid 520 13 Blomstølen Skånevik Breifonn Haukeligrend E 134 Kvanndalen Oslo SAUDA Holmevatn 9 Kvanndalen Storavassbu Holmevassåno VERNEOMRÅDET Fitjarnuten Etne Sauda Roaldkvam Sandvatnet Sæsvatn Løkjelsvatnhytta Saudasjøen Skaulen Nesflaten Varig verna Sloaros Breivatn Bjåen Mindre verneområdeVinje Svandalen n e VERNEOMRÅDAVERNEOVERNEOMRÅDADA I d forvalta av SVR r o Bleskestadmoen E 134 j Dyrskarnuten f a Ferdselsrestriksjonar: d Maldal Hustveitsåta u Lislevatn NR Bråtveit ROGALAND Vidmyr NR Haugesund Sa Suldalsvatnet Olalihytta AUST-AGDER Lundane Heile året Hovden LVO Hylen Jonstøl Hovden Kalving VINDAFJORD (25. april–31. mai) Sandeid 520 Dyrskarnuten Snønuten Hartevatn 1604 TjørnbrotbuTjø b tb Trekk Hylsfjorden (15. april–20. mai) 46 Vinjarnuten 13 Kvilldal Vikedal Steinkilen Ropeid Suldalsosen Sand Saurdal Dyraheio Holmavatnet Urdevasskilen Turisthytter i SVR SULDAL Krossvatn Vindafjorden Vatnedalsvatnet Berdalen Statsskoghytter Grjotdalsneset Stranddalen Berdalsbu Fjellstyrehytter Breiavad Store Urvatn TOKKE 46 Sandsfjorden Sandsa Napen Blåbergåskilen Reinsvatnet Andre hytter Sandsavatnet 9 Marvik Øvre Moen Krokevasskvæven Vindafjorden Vatlandsvåg Lovraeid Oddatjørn- Vassdalstjørn Gullingen dammen Krokevasshytta BYKLE Førrevass- Godebu 13 dammen Byklestøylane Haugesund Hebnes -

Stavanger – Ryfylke Hurtigbåt

Stavanger til RYfYlke Mandag til torsdag Rutenr. Ukedag Operatør Plattform StavangerHeng Sør-HidleTau Brimse Talgje Fogn JudabergSør-Bokn BYre HalsnøY EidssundHelgøY (FinnøY)Nord-HidleNesheim NedstrandVormestrandVikedal Sandeid Jelsa FoldøY Hebnes Marvik Ropeid Sand Sauda 504 Man–fre Norled 4 0535 0640 0555s 0630 0620 0610 518 Man–fre Rødne - 0615 0655 0625b 0640 0633b 0630b 518 Man–fre Rødne - 0705 0745 0740 0730 0725 0720 506 Man–fre Rødne 6 0710 0730b 0735b 0745a 0750 510 Man–fre Norled 4 0715 0735 0745 0750 0800 0810 0814b 0818 0900k 0946e 0955e 0835k 0840 0845k 0920e 0915e 0955e 518 Man–fre Rødne 3 1030 1050b 1100 1105 1115 1150 1145 1125 1130 1135 510 Man–tor Norled 5 1225 1245 1250 1255 1305 1310b 1320b 1330b 1335b 1340b 1506e 1515e 1350 1355 1400 1455b 1440k 1430 1515e 518 Man–fre Rødne 5 1400 1450b 1455b 1445 1425b 1555 1545b 1540b 1534 1529 1525 506 Man–fre Norled - 1505 1455 1510 506 Man–fre Rødne - 1535 1545 1550 1600 510 Man–tor Norled 4 1530 1555a 1600a 1605 1615 1625b 1635k 1811e 1820e 1650k 1655 1700 1715b 1745k 1735 1820e 518 Man–fre Rødne - 1610 1620 1625 1635 1640b 1645 504 Man–tor Norled 5 1645 1800b 1755b 1705 1715 1720 1725 520 Man–tor Rødne - 1735 1740 1745 1750b 1755b 1800b 1810b 1815b 1820a 510 Man–tor Norled 5 1945 2015 2030b 2035b 2045 2055b 2100b 2110b 2130b 2125bk 2200 518 Man–tor Rødne 5 2000 2015b 2017b 2020 2030b 2035 2040 2050 2100b 2102b 2105b 2110b 2130 2125b 2120b 518 Kun torsdag Rødne 5 2300 2315b 2317b 2320 2330b 2335b 2340b 2350 0000b 0002b 0005b 0015b 0030a 0025b 0020a Fotnoter a Anløpstid er ca.-tid og båten anløper kun hvis passasjerer skal gå i land på stedet. -

Lo I Nord-Rogaland 1918

LO I NORD-ROGALAND 1918 - 2018 EN JUBILEUMSBERETNING Utgiver: Arbeidernes Historielag i Rogaland Jens Zetlitz gate 21, 4008 Stavanger LO I NORD-ROGALAND 1918 - 2018 Telefon: 51 50 02 00 - sentralbord Folkets Hus EN JUBILEUMSBERETNING [email protected] HARALD DALE Formgiving: Petter Dimmen www.dimmen-design.no BIlDEREDAKSJoN: EgIl lARSEN PETTER DImmEN Trykk: KAI HANSEN TRYKKERI Papir: Artic Volum White Typografi: Frutiger Adobe Caslon LO I NORD-ROGALAND I SAMARBEID MED ARBEIDERNES HISTORIELAG I ROGALAND ISBN: 978-82-999352-5-8 INNHOLD FORORD 05 Forord LO i Nord-Rogaland markerer sitt 100-årsjubileum i 2018. Odda. I vår tid kan Ukraina-saken stå som eksempel på utford 06 Hilsen fra LO-leder Hans-Christian Gabrielsen Martin Tranmæl og den nye retning i fagbevegelsen han var den ringer fagbevegelsen står overfor i dag – belyst gjennom intervju 08 LO i Nord-Rogaland 1918 – 2018 – en jubileumsberetning ledende representanten for i tiden rundt første verdenskrig, med Fellesforbundets Helge Larsen. Intervjuformen står 10 En oppegående jubilant kjempet bl.a. for at fagbevegelsens arbeid lokalt skulle sentralt i Harald Dales behandling av det nyere stoffet, der ut - 13 LO-opprøret i Nord-Rogaland samordnes bedre – ved opprettelsen av lokale samorganisasjoner. viklingen i perioden søkes belyst i samtaler med sentrale tillits - 14 Også 1. mai-krøll i 1992 Sentralt i LO vant dette kravet fram mellom 1911 og 1923. valgte. Også ellers er det dypdykk i utvalgte og sentrale 15 Lederskifte i jubileumsåret Samorganisasjonen i Haugesund og omegn vedtas opprettet på hendelser og utviklingstrekk i 100-årsperioden som ligger til 17 I begynnelsen var det dyrtid, matmangel og klassekamp møte 3. -

4. the Norwegian North Sea

4. The Norwegian North Sea Eva K. Halland (Project Leader), Ine Tørneng Gjeldvik, Wenche Tjelta Johansen, Christian Magnus, Ida Margrete Meling, Stig Pedersen, Fridtjof Riis, Terje Solbakk, Inge Tappel 29 4.1 Geology of the North Sea Central Norwegian- Southern Horda Tampen Spur Møre Group System Series Stage North sea Danish Basin Viking Graben Platform Holo Basin U Calabria Plei QUATERNARY Gela Pia 62° Nordland Plio Zan Utsira Mess - Mio Skade NEOGENE Aquit Chat Vade Olig Rup Grid Grid Pria - Hordaland Frigg Balder Eoc Ypres Forties Sele Fiskebank Sele Hermod Hermod Hermod Sele Tampen Spur Than - Andrew Lista Lista Heimdal Heimdal Lista land Maureen Våle Våle Roga- Pal PALAEOGENE Dan Ekosk Ekosk Ekosk Ty Ty Våle Sogn GrabenHorda Maast Tor Tor Tor Jorsalfare Jorsalfare Hardråde Basin Camp Kyrre Platform Hod Kyrre Kyrre U Sant Hod Hod East ShetlandEast Coni Tryggvason Tryggvason Tryggvason Shetland Blodøks Blodøks Blodøks Tur Blodøks High Utsira Blodøks Svarte Cen Hidra Hidra Svarte Svarte Bergen Alb Rødby Rødby Rødby Mime Rødby Rødby Apt Sola Sola Sola Ran Sola Sola Sola Barr Mime Mime Oslo CRETACEOUS L Tuxen Tuxen Haut Åsgard Platform Åsgard Åsgard Åsgard Åsgard Mime Cromer Knoll Cromer Valang East ShetlandEast Stord Berr Mandal Sauda Draupne Basin Tith Farsund Flekkeord Draupne Eldsk Tau Brae Draupne U Kimm Ula Sogneord Oxf Haugesund Egersund Boknord Heather Heather Viking/Tyne/ Heather Call Sandnes Hugin Fensord Viking Graben Tarbert Krossord . Vestland Bath Øygarden Fault complex Øygarden Fault M Ness Ness Bajoc Bryne Fm Brent/ Fladen Bryne Fm Sleipner Fm Etive Aalen Oseberg JURASSIC Toarc Drake Drake Fjerritslev Cook Cook Stavanger Plienc Burton Utsira Dunlin L Sinem Nansen Amundsen Hett Johansen Gassum Eiriksson High Stat. -

This Chart Was Produced with the Assistance of Noreco, Lundin, Conoco Phillips and Other Members of the Diskos Consortium

This chart was produced with the assistance of Noreco, Lundin, Standard Lithostratigraphy of Oshore Norway Conoco Phillips and other members of the Diskos Consortium For details see: "The Geologic Time Scale 2012" by F.M. Gradstein, J.G. Ogg, M. Schmitz and G. Ogg (2012, published by Elsevier), and the Geologic TimeScale Foundation website: https://engineering.purdue.edu/Stratigraphy Southern Viking Northern Viking Updates and refinements of the standard lithostratigraphy offshore Norway Norwegian - Central Graben Central Graben trough Southern Northern South Western Chrono - Chronostratigraphy Graben Graben Tampen - Svalbard Legend All figures are interactive on www.nhm2.uio.no/norlex. Danish Basin South North Utsira - Stord Basin Graben - Hordapl. Norwegian Sea Norwegian Sea Barents Sea stratigraphy Age Era Period Epoch Age/Stage NO DK DK UK/NO GB NO W E W E W E W E SW NE S N Lt. Pleist./Gelasian 0 Quat. Pleistocene Lt. Pleist./Gelasian Bergen Bergen Nordland Gr Nordland Gr Tampen sst Mb. Naust Naust Nordland Piacenzian/Zanclean Pliocene Piacenzian/Zanclean Messinian 7.25 Messinian 7.25 Nordland Gr Hutton Sst. Neogene stratigraphy of the Norwegian Tortonian Utsira Stavanger Tortonian 11.63 central and northern North Sea 10 11.63 Nordland Gr Stavanger Serravallian 13.82 Serravallian 13.82 Utsira Molo Age Chrono- S. Viking N. Viking Northern Viking Langhian 15.97 0 Miocene Langhian 15.97 Molo Ma stratigraphy Graben Graben Graben (61 N) Hordaland Lark Kai Burdigalian 20.44 Burdigalian 20.44 Kai Pleisto- S N W E cene / “Nordland Group mudstones” 20 Neogene Lark Aquitanian 23.03 Aquitanian 23.03 Skade Pliocene - undefined Vade Freja Vade 5 Chattian 28.1 Chattian 28.1 Lark Upper Utsira Formation Utsira Oligocene Skade Humid terrestrial shales Miocene Fm. -

Forsand Strand Sauda Suldal Hjelmeland

Sauda Til sone 341 Røldal 227 Valevåg Breiborg 336336 239239 EkkjeEkkje HellandsbygdHellandsbygd 236236 Hellandsbygda SaudaSauda Brattland Brattlandsdalen 335335 Etne Sauda BratlandBratland 226 Espeland Vihovda Åbødalen Brekke Sandvikdalen RoaldkvamRoaldkvam 240 241241 Kastfosskrys 334334 Egne Hjem Utbjoa EtneEtne Saunes 236 Nærsonersone TTråsavikikaa Nesflaten Roaldkvam set 225 Saua Førde Gard Kalvavika st Ølen kirke Ølen Hytlingetong Gj EiodalenØlen skule den erdevik øst 332332 222 våg 235235 333333 Sveio HamrabHamrabø BrBråtveittveit Saudafjor 237237 224 Øvre Vats SvandalSvandal MaldalMaldal Bråtveit Mokleiv Hamrabø 223223 SandeidSandeid Sandeid Suldalsvatnet Fjellgardsvatnet Hylen Løland Tengesdal 223 331331 Østbø 238238 HylenHylen Sandvik VanvikVanvik 328328 Vindafjord Hylsfjorden SuldalseidSuldalseid 216 218 Sandeidfjorden 230230 Suldal Nordre Vikse Ørnes 228228 RopeidRopeid Skjold ft VikedalVikedal 217 Vikedal 330330 Helganes Vestre 228 Eskedalen 221221 Suldalseid SuldalsosenSuldalsosen n IlsvIlsvåg Ropeid Ølmedal Kvaløy Skipavåg Sand 230 Suldalsosen 229229 Roopeid 327 327327 kryss SandSand Kariås SkipevSkipevåg Lindum 329329 camping VasshusVasshus 200 Suldalslå 220 n Haugesund gen 205 219 Nedre Vats Vindafjorden Kvamen Førdesfjorden 234234 Skjoldastraumen Finnvik 231231 Vela Foss VormestrandVormestrand Sandsfjorde Yrkefjorden 232232 Øvrabvrabø Helland (Suldal) MarvikMarvik Øvrabø Nærsone Ersdal Gullingen 234 206 Vormeestrrandd Førland Kjølvik 322322 Mosvatnet Mos- Sandsa- Marvik 232 LovraeidetLovraeidet vatnet 214 Marvik kai vatnet -

Rivers, Reefs, and Deltas; Geomorphological Evolution of the Jurassic of the Farsund Basin, Offshore Southern Norway

Rivers, reefs, and deltas; Geomorphological evolution of the Jurassic of the Farsund Basin, offshore southern Norway Thomas B. Phillips*, Christopher A-L. Jackson, Rebecca E. Bell, Ayunda A. Valencia Basins Research Group (BRG), Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College, South Kensington Campus, Prince Consort Road, London, SW7 2BP, UK *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Reconstructing ancient depositional environments and sedimentary facies distributions is vital to understanding the development of petroleum systems, as well as offering insights into the wider evolution of a region. However, in many underexplored, ‘frontier’ basins the identification of sedimentary facies is only possible at sparsely located wells, which are only able to document different facies in one-dimension. This is especially problematic in petroleum-bearing basins, where we typically need to define the three-dimensional distribution and geometry of source, reservoir, and seal rocks to define a working petroleum system. However, 3D seismic reflection data are able to provide detailed imaging of the earth’s subsurface across multiple stratigraphic levels. Interrogation of these data through the analysis of seismic attributes offers the opportunity to map the geometry and distribution of different facies in three dimensions. In this study, we examine the Farsund Basin, an underexplored basin located offshore southern Norway. Despite it lying in the prolific and much-explored North Sea basin, only one well has been drilled in the basin, meaning we have a very poor understanding of its hydrocarbon resource potential. Furthermore, this E-trending basin is anomalous to the N-trending basins present regionally, having experienced a different tectonic evolution, meaning that regional depositional models may not be applicable. -

Eramet Norway

ERAMET NORWAY SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2016 Eramet Norway supplies manganese alloys to steel manufacturers all over the world – founded on Norwegian industrial traditions and the use of self-developed high technology. CONTENTS 04 We are in a good position, but we still have to become more sustainable! 06 ERAMET is a world leader in the production of manganese alloys 07 Eramet Norway – a part of ERAMET Group’s mangenese division 08 ERAMET – part of your daily life 10 Production of manganese alloys and consumption of raw materials 11 World-class, environmentally friendly technology 12 ERAMET operations in Norway 16 Green energy should pay for itself 19 World-leaders in environmental production 20 Greener production based on research 25 Work on new emissions licences 26 Sustainability reporting – carbon footprint 28 Innovation Norway innovating in Norway 30 Eramet Norway’s energy balance status in 2016 33 An inspirational apprenticeship that opens doors 34 Business Ethics has always been a priority for our operations 35 Social responsibility at Eramet Norway 35 Shaping the provision of training and skills development for the future 36 Ready to meet the demands of the future 38 0-emissions by 2050 39 Improvements in environmental performance 42 Stable operating processes result in good environmental performance 45 An all-out effort to achieve a reduced footprint 46 NewERA making progress 50 HES figures 51 HES policy 53 Plant emissions figures 56 Key financial figures 58 Focus on sustainability throughout the group 59 Success founded on trust LEADER We are in a good position, but we still have to become more sustainable! Eramet Norway is one of the tise and the fact that we are constantly improving the efficiency of our operations. -

Ryfylke Vassområde

Årsrapport 2017 og budsjett 2018 – Ryfylke vassområde www.vannportalen.no/ryfylke INNHALD 1. Om vassområde ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Innleiing ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Vassområdeutvalet ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Arbeidgruppa og vasskoordinator ............................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Korleis har vassområde jobba i 2017 ........................................................................................................ 5 Tiltaksgjennomføring................................................................................................................................... 5 Overvaking og problemkartlegging ............................................................................................................. 5 Vasskraft og revisjon ................................................................................................................................... 7 Møteverksemd ............................................................................................................................................ 8 1.3 Økonomi ...................................................................................................................................................