Nicholas of Cusa and Raymond Lull: Comparison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cusanus, on Learned Igorance-17Z8dxd

On Learned Ignorance Harries 1 Karsten Harries Nicholas of Cusa On Learned Ignorance Seminar Notes Fall Semester 2015 Yale University Copyright Karsten Harries On Learned Ignorance Harries 2 Contents 1. Introduction 3 Book One 2. Learned Ignorance 17 3. The Coincidence of Opposites 30 4. The Threat of Pantheism 47 5. The Power of Mathematics 61 6. Naming God 76 Book Two 7. The Shape of the Universe 90 8. Matter and Becoming 105 9. The Condition of the Earth 118 Book Three 10. The Need for Christ 131 11. Death and Resurrection 146 12. Faith and Understanding 162 13. Death, Damnation, and the Church 176 On Learned Ignorance Harries 3 1. Introduction 1 Many philosophers today have become uneasy about what philosophy has become and where it has led us. Nietzsche and Heidegger, Derrida and Rorty are just a few names. Their uneasiness mirrors widespread concern about the shape of our modern culture. As more and more begin to suspect that the road on which we have been travelling may be a dead end, attempt are made to retrace steps taken; a search begins for missed turns and for those who may have misled us. Among these Descartes has long occupied a special place as the thinker whose understanding of proper method helped found modern philosophy, science, and indeed the shape of our technological world. It is thus to be expected that attempts to question modernity, to confront it, in order perhaps to take a step beyond it, should have often taken the form of attempts to confront Descartes or Cartesian rationality. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow (Edmonton, Alberta) In cooperation with Sylvia Brown (Edmonton, Alberta) Falk Eisermann (Berlin) Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Heil (Heidelberg) Susan C. Karant-Nunn (Tucson, Arizona) Martin Kaufhold (Augsburg) Erik Kwakkel (Leiden) Jürgen Miethke (Heidelberg) Christopher Ocker (San Anselmo and Berkeley, California) Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 183 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Polemic and Dialogue in the Late Middle Ages Edited by Ian Christopher Levy Rita George-Tvrtković Donald F. Duclow LEIDEN | BOSTON Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtković, and Donald F. Duclow - 9789004274761 Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 12:32:35PM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Modern Philosophy

//FS2/CUP/3-PAGINATION/HRP/2-PROOFS/3B2/9780521846486C09.3D 173 [173–192] 2.5.2007 8:03AM 9 DERMOT MORAN Nicholas of Cusa and modern philosophy ‘‘Gatekeeper of the modern age’’ Nicholas of Cusa (Niklas Krebs, known as Cusanus, 1401–64), one of the most original and creative intellects of the fifteenth century,1 has been variously described as ‘‘the last great philosopher of the dying Middle Ages’’ (Alexandre Koyre´), as a ‘‘transition-thinker’’ between the medieval and modern worlds (Frederick Copleston),2 and as the ‘‘gatekeeper of the modern age’’ (Rudolf Haubst).3 He is a lone figure with no real successor although he had some influence on Copernicus, Kepler, Bruno, and, tangen- tially, on Descartes. The German Idealists showed some interest in Nicholas of Cusa but the real revival of his thought was stimulated by the neo-Kantian philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1874–1945) who called him ‘‘the first modern thinker’’ and by the existentialist Karl Jaspers.4 Cassirer compared him to Kant for his view that objects have to be understood in terms of the categories of our own thought.5 Other scholars, notably Alexandre Koyre´,6 Hans-Georg Gadamer7 Hans Blumenberg,8 Werner Beierwaltes,9 and Karsten Harries,10 all see him in a certain way as a harbinger of modernity.11 Yet his outlook is essentially conservative, aiming, as Hans Blumenberg has recognized, to maintain the medieval synthesis.12 Cusanus was a humanist scholar, Church reformer – his De concordantia catholica (On Catholic Concord, 1434) included proposals for the reform of Church and state – papal diplomat, and Catholic cardinal. -

Pál Bolberitz: the Beginnings of Hungarian Philosophy

A SZENT IS1V AN TIJDOMANYOS AKADEMIA SZEKFOGLALO ELOADASAI Uj Folyam. 2/2. szam Szerkeszti: STIRLING JANos OESSH fot.itkar PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK ,DE HOMINE" BY PETER CS6KAS LASKOI) BUDAPEST 2004 A SZENT IS1V AN TIJDOMANYOS AKADEMIA SZEKFOGLALO ELOADASAI Uj Folyam. 2/2. szam Szerkeszti: STIRLING JANos OESSH fot.itkar PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK ,DE HOMINE" BY PETER CS6KAS LASKOI) Magyarrryelven elhangzott a Matr~ar Tu:imdnyos A lwitfmia Felol1.J:lfJ3 tern11i1m 2003. novemher 25-in BUDAPEST 2004 Minden jog fenntartva, beleertve a btirminemu eljtirtissal val6 sokszorositds jogdt is © BOLBERITZ PAL 2004 KESZULT A SZENT ISTV ANTARSULAT, AZ APOSTOLI SZENTSZEK KONYVKIAOOJA NYOMDAJABAN. IGAZGATO: FARKAS OLIVER OESSH BUDAPEST, V. KOSSUTH LAJOS U. 1. PAL BOLBERITZ THE BEGINNINGS OF HUNGARIAN PHILOSOPHY (THE RECEPTION OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA IN THE WORK DE HOMINE BY PETER Cs6KAS LASK6I) The present study does not intend to get involved in the academic dispute flaring up from time to time to discuss whether there has ever been Hungarian philosophy or not. According to our view, Hungarian philosophy did, does and, hopefully, will exist, for it has its own proper ties. As it is well known, philosophy is the science inves tigating the ultimate principles and causes. It is not un common for the Hungarian spirit to examine the ultimate questions either. As expressed by the Latin phrases: pri mum vivere, -

NICHOLAS of CUSA's DEBATE with JOHN WENCK a Translation and an Appraisal of De Ignota Litteratura and Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae

NICHOLAS OF CUSA'S DEBATE WITH JOHN WENCK A Translation and an Appraisal of De Ignota Litteratura and Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae by JASPER HOPKINS THE ARTHUR J. BANNING PRESS MINNEAPOLIS The English translation of Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae is made from Nicolai de Cusa Opera Omnia, Vol. II, edited by Raymond Klibansky (Leipzig: F. Meiner, 1932). Third edition, 1988 (First edition, 1981) Copyright © 1981 by The Arthur J. Banning Press, Minneapolis, Min- nesota 55402. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 80-82908 ISBN 0-938060-40-6 458 1 A DEFENSE OF LEARNED IGNORANCE FROM ONE DISCIPLE TO ANOTHER (Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae Discipuli ad Discipulum) by NICHOLAS OF CUSA Our common teacher, master Nicholas of Cusa, now added to the Col- lege of Cardinals, once told me how well you understand the coinci- dences which he disclosed to us in the books of Learned Ignorance (presented to the Apostolic Legate)1 and in many of his other works. [He spoke of] your ardent wish to gather together everything which here and there flows from him regarding these matters. [He also re- ported] that you do not allow any of the learned men to pass by you without talking with them about this approach. [And he mentioned] that you have induced many who had despised this study to break for a short while with their long-standing habit of laboring with the Aris- totelian tradition and to give themselves over to these considerations, in the faith that something important lies hidden therein—[to give themselves] to the extent that with an inward relish they become more deeply attracted and come to realize that this approach differs from others as much as sight differs from hearing. -

Cusa Faith/Reason-Engl

PROLEGOMENA TO NICHOLAS OF CUSA’S CONCEPTION OF THE RELATIONSHIP OF FAITH TO REASON by JASPER HOPKINS © 1996 PROLEGOMENA TO NICHOLAS OF CUSA’S CONCEPTION OF THE RELATIONSHIP OF FAITH TO REASON “Ist der Weg des spekulativen Denkens, wenn dieses nicht eine ermüdende Spielerei wird, immer von einem Glauben her beschritten, von einem Glauben sei es der alten griechischen Fröm- migkeiten, sei es der asiatischen Glaubensweisen, sei es der christlichen?” —Karl Jaspers1 I Is there any such thing as the Cusan view of the relationship between faith and reason? That is, does Nicholas present us with clear concepts of fides and ratio and with a unique and consistent doctrine regarding their interconnection? If he does not, then the task before us is surely an impossible one: viz., the task of find- ing, describing, and setting in perspective a doctrine that never at all existed. For even with spectacles made of beryl stone or through the looking glass of Lewis Car- roll, we could not descry the totally nonexistent. Four lines of argument purport to show that the task before us is funda- mentally impossible. 1. First of all, it may be argued (a) that Nicholas of Cusa can have a coher- ent doctrine of faith and reason only if he has a generally coherent theory of knowl- edge and (b) that since his theory of knowledge is generally incoherent, so too must be the aforesaid doctrine, which is an intrinsic part of the theory of knowledge. Let us grant—for the sake of the argument—the disputable logic of this reasoning, and let us focus on the question of whether Nicholas does or does not have a viable gen- eral theory of knowledge. -

The Concept of Non-Duality in Śaṅkara and Cusanus

Comparative Philosophy Volume 12, No. 1 (2021): 98-110 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 / www.comparativephilosophy.org https://doi.org/10.31979/2151-6014(2021).120109 THE CONCEPT OF NON-DUALITY IN ŚAṄKARA AND CUSANUS JEROME KLOTZ ABSTRACT: When comparing diverse philosophical traditions, it becomes necessary to establish a common point of departure. This paper offers a comparative analysis of Advaita Vedānta Hinduism and esoteric Christianity, as represented by the two highly celebrated figures of Śaṅkara and Nicholas Cusanus, respectively. The common point of departure on which I base this comparison is the concept of “non-duality”—a concept that is fitting for at least two reasons. First, it is general enough to encompass both traditions, pervading the work of each figure, and thus allowing for a kind of “shared language.” Second, it is specific enough to identify a set of core and well-defined principles amenable to systematic study, chief among which are the notions of (1) the “Absolute” as an infinite unity that transcends all determinations (“no-thing”) and exceeds all oppositions (“not-other”), and (2) the world as an ontologically ambiguous “reflection” that simultaneously hides and manifests its meta- ontological Principle. In drawing these connections, I hope to show how the concept of non- duality provides the possibility for a mutual understanding among diverse traditions at the philosophical level. Keywords: Advaita Vedānta, metaphysics, mysticism, Nicholas Cusanus, non-duality, Śaṅkara 1. INTRODUCTION The concept of “non-duality” is not the exclusive possession of any one philosophical system. On the contrary, it can be found—mutatis mutandis—within religio- philosophical traditions the world over: from Philosophical Daoism, Mahāyāna Buddhism, and Advaita Vedānta Hinduism in the East, to Kabbalistic Judaism, esoteric Christianity, and mystical Islam in the West. -

A-Z Entries List

Alphabetical List of Entries Abelard, Peter Attributes, Divine Abortion Augustine of Hippo Action Augustinianism Adam Authority Adoptionism Agape Balthasar, Hans Urs von Agnosticism Bañezianism-Molinism-Baianism Albert the Great Baptism Alexandria, School of Baptists Alphonsus Liguori Barth, Karl Ambrose of Milan Basel-Ferrara-Florence, Council of Anabaptists Basil (The Great) of Caesarea Analogy Beatitude Angels Beauty Anglicanism Beguines Anhypostasy Being Animals Bellarmine, Robert Anointing of the Sick Bernard of Clairvaux Anselm of Canterbury Bérulle, Pierre de Anthropology Bible Anthropomorphism Biblical Theology Antinomianism Bishop Antinomy Blessing Antioch, School of Blondel, Maurice Apocalyptic Literature Boethius Apocatastasis Bonaventure Apocrypha Bonhoeffer, Dietrich Apollinarianism Book Apologists Bucer, Martin Apostle Bultmann, Rudolf Apostolic Fathers Apostolic Succession Calvin, John Appropriation Calvinism Architecture Canon Law Arianism Canon of Scriptures Aristotelianism, Christian Carmel Arminianism Casuistry Asceticism Catechesis Aseitas Catharism Athanasius of Alexandria Catholicism Atheism Chalcedon, Council of xiii Alphabetical List of Entries Character Diphysitism Charisma Docetism Chartres, School of Doctor of the Church Childhood, Spiritual Dogma Choice Dogmatic Theology Christ/Christology Donatism Christ’s Consciousness Duns Scotus, John Chrysostom, John Church Ecclesiastical Discipline Church and State Ecclesiology Circumincession Ecology City Ecumenism Cleric Edwards, Jonathan Collegiality Enlightenment -

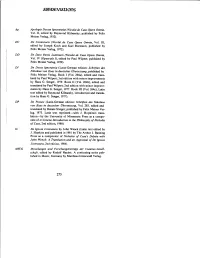

Notes to the Interpretive Study Longer Latin Passages That Stand by Them- Selves Are Not Italicized

aBBREV1atl ons Ap. Apologia Doctae Ignorantiae (Nicolai de Cusa Opera Omnia, Vol. II, edited by Raymond Klibansky; published by Felix Meiner Verlag, 1932). DC De Coniecturis (Nicolai de Cusa Opera Omnia, Vol. III, edited by Joseph Koch and Karl Bormann; published by Felix Meiner Verlag, 1972). DD De Dato Parris Luminum (Nicolai de Cusa Opera Omnia, Vol. IV ( Opuscula l), edited by Paul Wilpert; published by Felix Meiner Verlag, 1959). DI De Docta Ignorantia (Latin-German edition: Schriften des Nikolaus von Kues in deutscher Obersetzung, published by Felix Meiner Verlag. Book I (Vol. 264a), edited and trans- lated by Paul Wilpert; 3rd edition with minor improvements by Hans G. Senger, 1979. Book II (Vol. 264b), edited and translated by Paul Wilpert; 2nd edition with minor improve- ments by Hans G. Senger, 1977. Book III (Vol. 264c), Latin text edited by Raymond Klibansky, introduction and transla- tion by Hans G. Senger, 1977). DP De Possess (Latin-German edition: Schriften des Nikolaus von Kues in deutscher übersetzung, Vol. 285, edited and translated by Renate Steiger; published by Felix Meiner Ver- lag, 1973. Latin text reprinted—with J. Hopkins's trans- lation—by the University of Minnesota Press as a compo- nent of A Concise Introduction to the Philosophy of Nicholas of Cusa, 2nd edition, 1980). IL De Ignota Litteratura by John Wenck (Latin text edited by J. Hopkins and published in 1981 by The Arthur J. Banning Press as a component of Nicholas of Cusa's Debate with John Wenck: A Translation and an Appraisal of De Ignota Litteratura, 2nd edition, 1984). -

Nicholas of Cusa: Metaphysical Speculations: Volume Two

NICHOLAS OF CUSA: METAPHYSICAL SPECULATIONS: VOLUME TWO by JASPER HOPKINS THE ARTHUR J. BANNING PRESS MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA Introductory Sections reprinted here online by permission of Banning Press Library of Congress Control Number: 97-72945 ISBN 0-938060-48-1 Printed in the United States of America Copyright © 2000 by The Arthur J. Banning Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55402. All rights reserved. iv PREFACE With the English translation of the two Latin works contained in this present book, which is a sequel to Nicholas of Cusa: Metaphysical Speculations:[Volume One],1 I have now translated all2 of the major treatises and dialogues of Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464), except for De Concordantia Catholica.3 My plans call for collecting, in the near future, these translations into a two-volume paperback edition—i.e., into a Reader—that will serve, more generally, students of the history of philosophy and theology. Reasons of economy dictate that footnotes and introductory analyses be left aside, so that the prospective Reader cannot be thought of as a replacement for the more scholarly previous- ly published volumes. The present project was supported by a sabbatical leave granted by the University of Minnesota, with supplementary travel support from the University’s Office of International Programs and from the Mc- Knight Foundation by way of funds administered through the University of Minnesota. In the course of preparing this study I have examined, on site, the two extant Latin manuscripts of De Ludo Globi—one at the Cusanus Hospice in Bernkastel-Kues, Germany, the other at the Jagiellonian Library in Cracow, Poland. -

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions

Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions Edited by Andrew Colin Gow (Edmonton, Alberta) In cooperation with Sylvia Brown (Edmonton, Alberta) Falk Eisermann (Berlin) Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Heil (Heidelberg) Susan C. Karant-Nunn (Tucson, Arizona) Martin Kaufhold (Augsburg) Erik Kwakkel (Leiden) Jürgen Miethke (Heidelberg) Christopher Ocker (San Anselmo and Berkeley, California) Founding Editor Heiko A. Oberman † VOLUME 183 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/smrt Nicholas of Cusa and Islam Polemic and Dialogue in the Late Middle Ages Edited by Ian Christopher Levy Rita George-Tvrtković Donald F. Duclow LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www. knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover illustration: Opening leaf of ‘De pace fidei’ in Codex Cusanus 219, fol. 24v. (April–August 1464). Photo: Erich Gutberlet / © St. Nikolaus-Hospital/Cusanusstift, Bernkastel-Kues, Germany. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nicholas of Cusa and Islam : polemic and dialogue in the late Middle Ages / edited by Ian Christopher Levy, Rita George-Tvrtkovic, Donald F. -

Erasmus' Attitude Toward Islam in Light of Nicholas of Cusa's De Pace Fidei

ERASMUS’ ATTITUDE TOWARD ISLAM IN LIGHT OF NICHOLAS OF CUSA’S DE PACE FIDEI AND CRIBRATIO ALKORANI Nathan Ron The University of Haifa Abstract Reading Nicolas of Cusa’s works on Islam reveals a sharp distinction between his De pace fidei (1453) with its tolerant attitude and his Cribratio Alkorani (1461) with its much less tolerant approach. Some eight years passed from the appearance of De pace fidei until the publication of Cribratio Alkorani . I argue that in the period between the appearances of these books, Cusanus changed his attitude to Islam, and the Turkish threat may have been the reason. Certain historians have pointed to Desiderius Erasmus’ objection to the waging of crusades and to the term semichristiani, which Erasmus occasionally used in reference to Muslims. According to these historians, the term semichristiani echoed Cusanus’ optimistic view according to which the Turks were «half-Christian». However, I found that Cusanus never used this term in any of his writings, and that the term sits in Erasmus’ writings side by side with manifest contempt and degradation expressed toward the Turks. Thus, Erasmus’ rhetoric and hostile attitude toward the Turks and Islam was far from the moderation and toleration which Cusanus presented in his De pace fidei . In its attitude and spirit Erasmus’ De bello Turcico should be compared to Cusanus’ Cribratio Alkorani rather than to De pace fidei . Keywords Cusanus; Erasmus; Islam; Turks; ‘Semischristiani’ ; crusade Introduction In his Complaint of Peace (Querela pacis , 1517) Erasmus described France as the purest Christian land: «The law flourishes as nowhere else, nowhere has religion so retained its purity without being corrupted by commerce carried ________________________________________________________________ Revista Española de Filosofía Medieval, 26/1 (2019), ISSN: 1133-0902, pp.