Creating Healthy Work Environments 2019 Promoting Civility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wednesday, October 10, 2018 Schedule-At-A-Glance

Wednesday, October 10, 2018 Schedule-at-a-Glance 6:30 am – 7:10 am ONSITE REGISTRATION/NETWORKING – LOBBY – TEXAS WOMAN’S Continental Breakfast UNIVERSITY 7:10am – 7:30am ACHE-SETC Welcome & Opening Session Paul C. O’Sullivan, FACHE, President, ACHE-SETC Todd A. Caliva, FACHE, President, Educational Foundation of the SETC Opening Session Speaker: Major General (Ret.) Mary Saunders, Executive Director, Institute for Women’s Leadership, Texas Woman’s University, Denton, TX 7:30am – 9:00 ACHE F2F Panel Discussion (1.5 CEUs) #1: Leadership Development for Developing Leaders Moderator: Deborah L. Smith, PhD, RT(R), MBB, MCF, Jonah Strategy Consultant, Mentor/Coach – Aurora, CO Panelists: Ashley McClellan, FACHE, President/CEO, Woman's Hospital of Texas – Houston, Texas Judy Le, President, TakeRoot Leadership – Houston, TX J. Bryan Bennett, Executive Director, Healthcare Center of Excellence, Chicago, IL 9:00am = 9:15 BREAK 9:15am – 10:45 ACHE F2F Panel Discussion (1.5 CEUs) #2: Successfully Leading Change in Healthcare Organizations Moderator: Jack Buckley, FACHE, Executive-in-Residence, Texas A&M MHA Program – College Station, TX Panelists: Deborah L. Smith, PhD, RT(R), MBB, MCF, Strategy Consultant, Mentor/Coach – Aurora, Colorado Carla Braxton, MD, Chief Quality Officer, Houston Methodist, West/Houston Methodist St, Catherine, Katy, TX Troy Villarreal, FACHE, President, HCA Gulf Coast Division, Houston, TX 10:45am – 11:00 BREAK 11:00am – 12Noon Breakout Sessions W1A-1E – 60 Minute Concurrent Sessions W1A – Special Topic – Guest Speaker -

1:30 Pm TMC Executive Offices Council Members Present

VOLUNTEER SERVICES COUNCIL September 26, 2017 12 – 1:30 p.m. TMC Executive Offices Council Members Present: Courtney Hoyt, Harris Health System Jessica Segal, Harris Health System Estelle Luckenbach, San Jose Clinic Marion Schoeffield, Harris County Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program Millicent Lacy, Texas Children’s Hospital Ian Todd, Harris Health System Sarah King, Ronald McDonald House Houston Helen Villaseñor, Shriner’s Hospital for Children Cheronda Rutherford, Houston Methodist Hospital Kellye Moran, LifeGift Organ Donation Center Jacquelyn Jones, Memorial Hermann Mayra Cantu, Memorial Hermann Irma Almaguer, TIRR Memorial Hermann Frankie Duenes, Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center Guests Present: Esmerelda Soria- Mabin Armand Viscarri TMC Members Present: Carter Fitts, Marketing Associate Tatum Boatwright, Marketing Manager Shelby Wolfenberger, Office Manager MEETING HIGHLIGHTS: I. Welcome & Introductions: Frankie Duenes, Gulf Coast Regional Blood Center • The meeting commenced shortly after noon with everyone going around the table and introducing themselves. We started off on an uplifting note sharing a few stories about our community coming together during Hurricane Harvey. II. Volunteer Workshop Planning: • The council will be hosting their second annual volunteer services workshop on October 24th from 8:30am-2:00pm at Ben Taub Hospital. • This half-day program will provide all attendees with three informational sessions that relate to volunteering. Lunch will be provided and the opportunity to tour the facility will conclude the program. We hope to see you all there! • The planned agenda is as follows: • 8:30 - 9 a.m. Check in and Coffee/Drinks • 9 - 9:45 a.m. - Session 1: Empathetic Communication – Harris Health Team • 10 - 10:45 a.m. -

Agendas May Be Obtained in Advance of the Court Meeting in the Office of Coordination

NOTICE OF A PUBLIC MEETING August 7, 2015 Notice is hereby given that a meeting of the Commissioners Court of Harris County, Texas, will be held on Tuesday, August 11, 2015 at 10:00 a.m. in the Courtroom of the Commissioners Court of Harris County, Texas, on the ninth floor of the Harris County Administration Building, 1001 Preston Avenue, Houston, Texas, for the purpose of considering and taking action on matters brought before the Court. Agendas may be obtained in advance of the court meeting in the Office of Coordination & Budget, Suite 938, Administration Building, 1001 Preston Avenue, Houston, Texas, in the Commissioners Court Courtroom on the day of the meeting, or via the internet at www.harriscountytx.gov/agenda. Stan Stanart, County Clerk and Ex-Officio Clerk of Commissioners Court of Harris County, Texas Olga Z. Mauzy, Director Commissioners Court Records HARRIS COUNTY, TEXAS 1001 Preston, Suite 938 Houston, Texas 77002-1817 (713) 755-5113 COMMISSIONERS COURT Ed Emmett El Franco Lee Jack Morman Steve Radack R. Jack Cagle County Judge Commissioner, Precinct 1 Commissioner, Precinct 2 Commissioner, Precinct 3 Commissioner, Precinct 4 No. 15.14 A G E N D A August 11, 2015 10:00 a.m. Opening prayer by Reverend Deacon Iakovos Varcados of Saint Basil the Great Greek Orthodox Church in Houston. I. Departments 15. District Courts 16. Travel & Training 1. Public Infrastructure a. Out of Texas a. County Engineer b. In Texas 1. Construction Programs 17. Grants 2. Engineering 18. Fiscal Services & Purchasing 3. Right of Way a. Auditor b. Flood Control District b. -

Tackling Tropical Diseases

THE OFFICIAL NEWS OF THE TEXAS MEDICAL CENTER SINCE 1979 — VOL. 36 / NO. 8 — JUNE 2014 Tackling Tropical Diseases Once thought to affect only developing countries, neglected tropical diseases are threatening populations in the Gulf Coast region. INSIDE: PEDIATRIC ROBOTIC SURGERY, P. 6 » DESIGNING A LANDSCAPE OF HEALTH, P. 14 » INNOVATION FOR CEREBRAL PALSY THERAPY, P. 26 ISABELLA PLACE WOODLAND PARK VIEWS RENOIR PLACE From the $430’s From the $770’s From the $770’s Museum District Heights River Oaks Free-Standing • Roof Terrace Free-Standing • Private Driveway Free-Standing • Private Driveway ROSEWOOD STREET ESTATES WEST BELL TERRACE HERMANN PARK COURT From the $480’s From the $610’s From the $430’s Museum District Montrose Medical Center Free-Standing • Privately Fenced Yard Roof Terrace • Downtown Views Free-Standing • Private Yards 713-868-7226 5023 Washington Avenue www.UrbanLiving.com www.urban Inc, TREC Broker #476135 NMLS: 137773 TMC | PULSE//TABLE of CONTENTS june 2014 5 12 14 19 A Vision for Health Policy Illuminating Data Industry Spotlight: Tackling Tropical Diseases ................................. ................................. Roksan Okan-Vick ................................. Arthur Garson Jr., M.D., MPH, is named Ayasdi helps partners map patterns Houston Parks Board Roughly a billion people in the world director of the emerging Texas Medical and relationships in health care data. ................................. suffer from a neglected tropical disease. Center Health Policy Institute. The executive director shares her A team of researchers at Baylor College passion for Houston’s green space, of Medicine have built a program they and the Texas Medical Center’s role hope will help change that. in creating a more connected city. -

A Program of Harris County Protective Services for Children and Adults George Ford, Executive Director

A Program of Harris County Protective Services for Children and Adults George Ford, Executive Director Ginger Harper, Program Director 6300 Chimney Rock Houston, Texas 77081 http://www.hc-ps.org/ 2013-2014 RESOURCE DIRECTORY FOR HARRIS COUNTY Designed for Agencies Serving Youth & Families This directory includes only the most commonly used nonprofit, United Way, church and government resources available to the general public and is not intended to be complete. Private, for profit services are sometimes included if there is a lack of nonprofits for that service, or they offer some free or specialized program to the community. It is intended to be an organized informational guide for professionals working with youth. Inclusion does not denote endorsement or recommendation. Directory information rapidly becomes outdated and a new directory is published annually. If you find errors or have information on new resources, please feel free to contact us so that we can stay as up-to-date as possible. For current information regarding state agencies, we recommend you contact the agency. A special thank you to the DHHS: Administration on Children, Youth and Families for underwriting the resource directory. Edited by: Paula Wilkes: [email protected] Kristen Ballard: [email protected] Revised by Yvette Torres and CYS Staff For additional copies call: 713-295-2530 Table of Contents I. Community Youth Services 4 II. Adoption 7 III. AIDS Resources 8 A. Direct Services 8 B. Information and Referral 11 C. Education 12 IV. Basic Needs 12 A. Clothing 12 B. Emergency Assistance 12 C. Food and Food Stamps 16 D. -

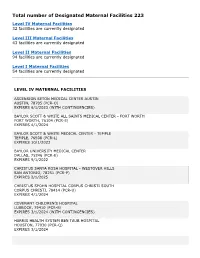

Designated Maternal Facilities 223

Total number of Designated Maternal Facilities 223 Level IV Maternal Facilities 32 facilities are currently designated Level III Maternal Facilities 43 facilities are currently designated Level II Maternal Facilities 94 facilities are currently designated Level I Maternal Facilities 54 facilities are currently designated LEVEL IV MATERNAL FACILITIES ASCENSION SETON MEDICAL CENTER AUSTIN AUSTIN, 78705 (PCR-O) EXPIRES 6/1/2023 (WITH CONTINGENCIES) BAYLOR SCOTT & WHITE ALL SAINTS MEDICAL CENTER - FORT WORTH FORT WORTH, 76104 (PCR-E) EXPIRES 4/1/2024 BAYLOR SCOTT & WHITE MEDICAL CENTER - TEMPLE TEMPLE, 76508 (PCR-L) EXPIRES 10/1/2023 BAYLOR UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER DALLAS, 75246 (PCR-E) EXPIRES 9/1/2022 CHRISTUS SANTA ROSA HOSPITAL - WESTOVER HILLS SAN ANTONIO, 78251 (PCR-P) EXPIRES 2/1/2025 CHRISTUS SPOHN HOSPITAL CORPUS CHRISTI SOUTH CORPUS CHRISTI, 78414 (PCR-U) EXPIRES 4/1/2024 COVENANT CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL LUBBOCK, 79410 (PCR-B) EXPIRES 3/1/2024 (WITH CONTINGENCIES) HARRIS HEALTH SYSTEM BEN TAUB HOSPITAL HOUSTON, 77030 (PCR-Q) EXPIRES 3/1/2024 JOHN PETER SMITH HOSPITAL FORT WORTH, 76104 (PCR-E) EXPIRES 5/1/2024 (WITH CONTINGENCIES) LAS PALMAS MEDICAL CENTER A CAMPUS OF LPDS HEALTHCARE EL PASO, 79902 (PCR-I) EXPIRES 3/1/2025 MEDICAL CITY DALLAS HOSPITAL DALLAS, 75230 (PCR-E) EXPIRES 2/1/2023 MEDICAL CITY PLANO PLANO, 75075 (PCR-E) EXPIRES 8/1/2023 MEMORIAL HERMANN - TEXAS MEDICAL CENTER HOUSTON, 77030 (PCR-Q) EXPIRES 5/1/2024 METHODIST HOSPITAL SAN ANTONIO, 78229 (PCR-P) EXPIRES 2/1/2023 NORTH AUSTIN MEDICAL CENTER AUSTIN, 78758 (PCR-O) EXPIRES 6/1/2023 (WITH CONTINGENCIES) NORTH CENTRAL BAPTIST HOSPITAL SAN ANTONIO, 78258 (PCR-P) EXPIRES 1/1/2025 PARKLAND MEMORIAL HOSPITAL DALLAS, 75235 (PCR-E) EXPIRES 8/1/2023 ST. -

RHP Plan Update Provider Form

RHP Plan Update Provider Form This page provides high-level information on the various inputs that a user will find within this template. Cell Background Description Sample Text Required user input cell, that is necessary for successful completion Sample Text Pre-populated cell that a user CANNOT edit Sample Text Pre-populated cell that a user CAN edit Sample Text Optional user input cell DY7-8 Provider RHP Plan Update Template - Provider Entry Progress Indicators Section 1: Performing Provider Information Complete Section 2: Lead Contact Information Complete Section 3: Optional Withdrawal From DSRIP Complete Section 4: Performing Provider Overview Complete Section 5: DY7-8 DSRIP Total Valuation Complete Section 1: Performing Provider Information RHP: 3 TPI and Performing Provider Name: 137949705 - Houston Methodist Hospital Performing Provider Type: Hospital Ownership: Private TIN: 17411801552007 Physical Street Address: 6565 Fanin Street City: Houston Zip: 77030 Primary County: Harris Additional counties being served (optional): y yp y p ; , p y y p Section 2: Lead Contact Information Lead Contact 1 Lead Contact 2 Lead Contact 3 Contact Name: Carolyn Belk Heather Chung Ekta Patel 6560 Fannin Street, Scurlock Suite 6560 Fannin, Scurlock Tower,Suite Street Address: 1707 Sunset Blvd. 1562 1562 City: Houston Houston Houston Zip: 77005 77030 77030 Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Phone Number: 832-667-5883 281-755-5391 (832) 696-3938 Phone Extension: Lead Contact or Both: Both Both Both Please note that a contact designated "Lead Contact" will be included in the RHP Plan and on the DSRIP Provider Distribution List. A contact designated as "Both" will be included in the RHP Plan, on the DSRIP Provider Distribution List, and will be given access to the DSRIP Online Reporting System. -

Medicaid Pcp Provider Directory Directorio De Proveedores December/Deciembre 2017

MEDICAID PCP PROVIDER DIRECTORY DIRECTORIO DE PROVEEDORES DECEMBER/DECIEMBRE 2017 JEFFERSON SERVICE AREA ÁREA DE SERVICIO DE JEFFERSON Thousands of doctors to choose from, including Memorial Hermann and Texas Children’s Hospital 24-Hour Nurse Help Line Contact lenses and dental services for children and adults Much more! Miles de doctores de donde escoger incluyendo Memorial Hermann y el hospital de Texas Children’s Línea de Ayuda de Enfermeras las 24 horas del día Lentes de contacto y servicios dentales para niños y adultos ¡Y mucho más! CommunityCares.com 713.295.2294 | 1.888.760.2600 JE8H-1217 Community Health Choice Texas, Inc.. is an affiliate of the Harris Health System. Community Health Choice Texas, Inc. es un afiliado de Harris Health System. Community Health Choice Healthy Members at our Houston Astros event Miembros sanos de Community Health Choice en nuestro evento de los Houston Astros FOUR EASY STEPS CUATRO PASOS TO MEMBERSHIP FÁCILES PARA INSCRIBIRSE Step 1 Find your enrollment form. Paso 1 Encuentre su forma de inscripción. Write Community Health Choice Plan under Escriba Community Health Choice Plan Step 2 “Health Plan Name” as your first choice for Paso 2 en el cuadro “Health Plan Name” como each person being covered. su primera preferencia para cada persona cubierta. Pick a main doctor. Step Seleccione a un médico principal. 3 • Find your doctor listed under your city. Paso 3 • Encuentre a un médico en su ciudad. • Then, under “Primary Care Provider Name,” write the name of your first • Después, bajo “Primary Care Provider and second choice for doctors for each Name,” escriba el nombre de su person being covered. -

How to Get Your Harris Health Financial Assistance

How to Get Your Harris Health Financial Assistance There is no cost to make a Harris Health Financial Assistance Application To obtain Harris Health financial assistance you must complete Harris Health’s “Application for Financial Assistance.” Be sure you, your spouse, and ALL children between 18 and 26 years old who live with you sign and date the form. For Renewal Applicant (except Medicare applicant): If your name, address, marital Mail Application to: status, legal status, number of household member(s), and/or health care coverage has Harris Health Financial Assistance Program not changed since the expiration of your prior application, please complete and submit P.O. Box 300488, Houston, TX 77230 this application along with your family gross income for the past 30 days only. Please visit the website below for more information: https://www.harrishealth.org/access- care-hh/eligibility. Harris Health staff is able to enroll you in patient assistance programs available with drug manufactures if you complete the Medication Assistance Program (MAP) Consent and Authorization (Form #283233). This form allows Harris Health to share your health information requested by drug manufacturers and to sign other forms that are necessary to complete your application if you qualify for assistance. Please Provide Harris Health copies of: 1. Identification of you and if applicable, your spouse: Provide either: (1) Marriage license/IRS 1040, if married; (2) Declaration and Registration of Informal Marriage, if marriage is common law; or (3) Other proof of marriage and common law marriage AND provide one of the following forms of picture identification: (1) State-issued driver license; (2) State-issued ID card; (3) Current student ID; (4) Current employee job badge; (5) U.S. -

A Year to Remember. a Future to Embrace

A YEAR TO REMEMBER. A FUTURE TO EMBRACE. 2018 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY 1 Unexpected challenges bring out our best 2 For more than 50 years, Harris Health System has served as the safety net for the people Our vision of Harris County, providing exceptionally Harris Health will become the premier public high-quality healthcare to those most in need. academic healthcare system in the nation. Hurricane Harvey made this last fiscal year even more eventful than most, which is why we are especially proud to present this annual report. Our mission It is our privilege and our passion to be here, Harris Health is a community-focused as always, sharing our community’s triumphs academic healthcare system dedicated to and challenges while working to provide the improving the health of those most in need in best care, the latest technology and the most Harris County through quality care delivery, innovative healthcare services. coordination of care and education. 3 Message to our community No look back at the past year can ignore the devastating storm that dominated our lives and headlines. As Harvey’s drama unfolded, we saw Houstonians come together in amazing ways. But Harvey also confirmed something we’ve known for more than 50 years. As the health system for those most in need in our community, we have a critical responsibility to always be ready to provide the highest level of treatment and service. We are pleased to be making substantial investments and improvements throughout our system. Vital renovations at Ben Taub Hospital are moving forward. We’ve added home-based dialysis and Houston Hospice care programs. -

Harris Health Adminstrative Memo

Fiscal Year 2022 Operating and Capital Budget Special Called Board Meeting and Budget Workshop January 14, 2021 PROPOSED FISCAL YEAR 2022 OPERATING AND CAPITAL BUDGET Executive Summary and Budget Narrative………………………...................................................3 - 18 Statement of Revenue and Expenses……………………………….…………..………………....19 Statistical Highlights…………………………………………...............................................................20 Capital Budget Summary…………………………………………….……………………..............21 Capital Project Highlights (Major Highlights)..……………………….…………………………....22 APPENDIX Statistical Highlights Graphs…………………………………………………...………….…24 - 26 Harrishealth.org 2 Harris Health System FY 2022 Operating & Capital Budget Executive Summary Harris Health System Budget – Fiscal Year 2022 (March 2021 to February 2022) The proposed Fiscal Year 2022 Operating and Capital Budget for Harris Health System demonstrates its unwavering dedication to caring for the community and for those most in need in Harris County. The demand for services in Harris County stems from a large uninsured population of more than one million people, equivalent to an uninsured rate of over 20 percent. Harris Heath provides acute, emergency, trauma, and ambulatory care services as the County's key safety net provider for three hundred thousand indigent and low-income patients. While the COVID-19 pandemic strained the System’s capacity and resources, management’s resolve to move through the challenges coupled with the imperative to improve patient safety and outcomes, continues to inform its vision and strategy for FY 2022 and beyond. Based on the solid financial foundation built over the last five fiscal years, Harris Health recommends budgeting a 2.0 percent operating margin for FY 2022. The proposed annual Operating Budget for the fiscal year ending February 28, 2022 reflects a margin of $37.7 million, which underlines the ongoing effort to manage operations and to be able to reinvest in the services we provide and in the infrastructure of the system. -

Star Harris PCP Directory

MEDICAID PCP PROVIDER DIRECTORY DIRECTORIO DE PROVEEDORES DECEMBER/DECIEMBRE 2017 HARRIS SERVICE AREA ÁREA DE SERVICIO DE HARRIS Thousands of doctors to choose from, including Memorial Hermann and Texas Children’s Hospital 24-Hour Nurse Help Line Contact lenses and dental services for children and adults Much more! Miles de doctores de donde escoger incluyendo Memorial Hermann y el hospital de Texas Children’s Línea de Ayuda de Enfermeras las 24 horas del día Lentes de contacto y servicios dentales para niños y adultos ¡Y mucho más! CommunityHealthChoice.org 713.295.2294 | 1.888.760.2600 HA79-1217 Community Health Choice Texas, Inc. is an affiliate of the Harris Health System. Community Health Choice Texas, Inc. es un afiliado de Harris Health System. Community Health Choice Healthy Members at our Houston Astros event Miembros sanos de Community Health Choice en nuestro evento de los Houston Astros FOUR EASY STEPS CUATRO PASOS TO MEMBERSHIP FÁCILES PARA INSCRIBIRSE Step 1 Find your enrollment form. Paso 1 Encuentre su forma de inscripción. Write Community Health Choice Plan under Escriba Community Health Choice Plan Step 2 “Health Plan Name” as your first choice for Paso 2 en el cuadro “Health Plan Name” como each person being covered. su primera preferencia para cada persona cubierta. Pick a main doctor. Step Seleccione a un médico principal. 3 • Find your doctor listed under your city. Paso 3 • Encuentre a un médico en su ciudad. • Then, under “Primary Care Provider Name,” write the name of your first • Después, bajo “Primary Care Provider and second choice for doctors for each Name,” escriba el nombre de su person being covered.