Reflections on Konrad Hammann's Biography of Rudolf Bultmann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of the Fundamentals of Martin Luther's Theology in The

The Study of the Fundamentals of Martin Luther’s Theology in the Light of Ecumenism 1 Tuomo Mannermaa Translated and edited by Kirsi Stjerna It is not unusual in the history of academic disciplines that new ideas concerning the fundamentals of a particular discipline emerge either by accident or as a result of impulses from another field of scholarship. This is the case also in today’s Luther research. Two particular fields can be named from most recent history, fields with significant impulses for new insights: ecumenism and philosophy. The philosophical impulses are connected with the task of locating Luther’s theology in regard to both scholasticism, which preceded Luther, and the philosophy of the modern times, which succeeded him. Ecumenism presents its own challenges for Luther research and Lutheran theological tradition. It is the latter issue that I wish to address here, touching upon the issues related to philosophy only as far as it is helpful in light of ecumenical questions at stake. The ecumenical impulses originate, above all, from two sources: Lutheran–Orthodox theological discussions, on the one hand, and Lutheran–Catholic theological encounters, on the other. The challenge issued to Luther research by Lutheran–Orthodox discussions lies in the theme “Luther and the doctrine of divinization,” whereas Lutheran–Catholic cooperation in Luther research has set out to clarify the theme, “Luther as a theologian of love.” Especially the late Catholic Luther specialist Peter Manns has unraveled the latter topic wit h his fruitful Luther interpretation. The first of these two topics, “Luther and theosis (divinization),” is fundamental in the sense that it gives expression to the patristic standard of comparison that all these three denominations share and that can serve as a starting point in their process toward a common understanding. -

A Philosophical Audacity

A Philosophical Audacity Barth’s Notion of Experience Between Neo-Kantianism and Nietzsche1 Anthony Feneuil [email protected] This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: “A Philosophical Audacity: Barth’s Notion of Experience Between Neo-Kantianism and Nietzsche“, which has been published in final form at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijst.12077/full. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving Abstract: This article addresses Barth’s dialectical notion of experience in the 1920s. I argue that the theoretical problem raised by recent studies on Barth’s notion of experience after his break with liberalism (i.e., the apparent inconsistency between Barth’s move towards an increasingly neo-Kantian understanding of experience and his emphasis on the existential and psychological dimensions of experience) can be solved by the hypothesis of a Nietzschean influence on Barth's epistemology in the 1920s. I defend not only the historical plausibility but also the conceptual fecundity of such a hypothesis, which casts a new light on Barth’s relation to philosophy and the notion of experience, and lays the basis for a consistent Barthian theology of experience. *** Theology is not a discreet slice of knowledge you could simply add to one philosophy or other. It exists nowhere but through philosophy, and that is why Barth’s theological innovation cannot manifest itself apart from philosophical innovation. Barth is not a philosopher, and he does not explicitly develop his concepts in a philosophical way. But Barth repeatedly claims we cannot grant theology an extraordinary status among human discourses. -

Christianity and Liberalism

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Christianity and Liberalism EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:19 PM 1 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:19 PM 2 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Christianity and Liberalism J. Gresham Machen, D.D. New Edition William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan / Cambridge, U.K. EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:19 PM 3 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen First published 1923 New edition published 2009 by Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. All rights reserved Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 / P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K. Printed in the United States of America 15141312111009 7654321 ISBN 978-0-8028-6499-4 ISBN 978-0-8028-6488-8 (Westminster Edition) www.eerdmans.com EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:20 PM 4 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen To My Mother EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:20 PM 5 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:20 PM 6 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Contents - Foreword, by Carl R. Trueman ix Acknowledgments xvi Preface xvii I. Introduction 1 II. Doctrine 15 III. -

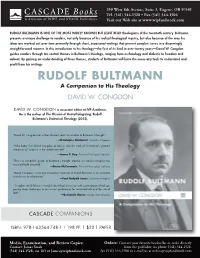

RUDOLF BULTMANN IS ONE of the MOST WIDELY KNOWN but LEAST READ Theologians of the Twentieth Century

199 West 8th Avenue, Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401 CASCADE Books Tel. (541) 344-1528 • Fax (541) 344-1506 A division of WIPF and STOCK Publishers Visit our Web site at www.wipfandstock.com RUDOLF BULTMANN IS ONE OF THE MOST WIDELY KNOWN BUT LEAST READ theologians of the twentieth century. Bultmann presents a unique challenge to readers, not only because of his radical theological inquiry, but also because of the way his ideas are worked out over time primarily through short, occasional writings that present complex issues in a disarmingly straightforward manner. In this introduction to his theology—the first of its kind in over twenty years—David W. Congdon guides readers through ten central themes in Bultmann’s theology, ranging from eschatology and dialectic to freedom and advent. By gaining an understanding of these themes, students of Bultmann will have the necessary tools to understand and profit from his writings. RUDOLF BULTMANN A Companion to His Theology DAVID W. CONGDON DAVID W. CONGDON is associate editor at IVP Academic. He is the author of The Mission of Demythologizing: Rudolf Bultmann’s Dialectical Theology (2015). “David W. Congdon has written the best short introduction to Bultmann’s thought.” —Christophe Chalamet, University of Geneva “Who better than David Congdon to take us into the work of Christianity’s greatest interpreter of Scripture in the modern period?” —James F. Kay, Princeton Theological Seminary “This is a wonderful ‘guide’ to Bultmann’s thought. Indeed, it is hard to imagine one more perfectly executed.” —Bruce McCormack, Princeton Theological Seminary “David Congdon’s lucid and innovative treatment of Rudolf Bultmann is an excellent contribution to scholarship.” —Paul Dafydd Jones, University of Virginia “Congdon sets Bultmann’s thought into critical discussion with contemporary theology, posing sharp challenges to our current preferences for ressourcement and the rule of faith.” —Benjamin Myers, Charles Sturt University CASCADE COMPANIONS ISBN: 978-1-62564-748-1 | 198 PP. -

A Christian Neo-Confucian Dialogue by Contrasting the Anthropological Views of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong for the Development of Chinese Theological Anthropology

Contrast the Differences: A Christian Neo-Confucian Dialogue By Contrasting the Anthropological Views of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong For the Development of Chinese Theological Anthropology By CHAN, Hoi Yan A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Knox College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Theology awarded by Knox College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by CHAN, Hoi Yan 2012 Contrast the Differences: A Christian Neo-Confucian Dialogue By Contrasting the Anthropological Views of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong For the Development of Chinese Theological Anthropology CHAN, Hoi Yan Doctor of Theology, 2012 Knox College, University of Toronto Abstract The thesis employs the method of contrast of a Chinese scholar Vincent Shen to compare and contrast the anthropologies of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong, with the goal of achieving a constructive inner dialogue made explicit for the development of a contextual Chinese theological anthropology. When the anthropologies of Barth and Xiong are put side by side for contrast, their views are clearly different from each other. However, in the inner dialogue, it is found that the perspectives of Barth and Xiong are not absolutely contradictory. It appears that Barth and Xiong shared several similarities in their observations of some phenomena of humanity, though they adopted different perspectives to interpret these phenomena. As Barth and Xiong are so different from each other on their cultural and academic backgrounds, it is interesting that they do come to similar observation on the phenomena of humanity, yet it is also argued that parallels should not be easily drawn. -

Karl Barth's Social Philosophy, 1918 -1933

KARL BARTH'S SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY, 1918 -1933 Peter John Holmes Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Divinity University of Glasgow June 2001 The enterprise of theological ethics is not one with which to trifle. It must be taken up properly - and this can mean only on the assumption that the command of the grace of God is its sole content - or it is better left alone. ' Karl Barth, Chin-ch Dogmatics 11/2p. 533. ii ABSTRACT This thesis is a contribution to the contemporary reassessment of Karl Barth's social philosophy. A close reading of the English translation of the text of a series of posthumously published lectures on ethics which Barth gave in the universities of Münster and Bonn between 1929 and 1933 is the basis of the work. Previous literature includes no discussion of the lectures. The thesis argues that the lectures show the foundation of Barth's thinking both of theology as a science and of ethics as a part of dogmatics, and that his subsequent work developed these ideas. Barth's intellectual debt to Hegel is recognised by showing that he returns to the fundamental theological questions of the relationship between faith and reason, and truth and method in the form in which Hegel discussed them at the end of the nineteenth century. The thesis acknowledges the influence of Barth's helper, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, and contrary to other opinions claims that the impact of Wilhelm Herrmann's thinking on Barth remained until 1933. -

Assessing the Work of Rudolf Bultmann

Foundations and Facets FORUM third series 3,2 fall 2014 Assessing the work of Rudolf Bultmann lane c. mcgaughy Preface 5 schubert m. ogden The Legacy of Rudolf Bultmann and the Ideal of a Fully Critical Theology 9 philip devenish Reflections on Konrad Hammann’s Biography of Rudolf Bultmann—with Implications for Christology 21 william o. walker, jr. Demythologizing and Christology 31 gerd lüdemann Kêrygma and History in the Thought of Rudolf Bultmann 45 jon f. dechow The ‘Gospel’ and the Emperor Cult From Bultmann to Crossan 63 publisher Forum, a biannual journal first published in Polebridge Press 1985, contains current research in biblical and cognate studies. The journal features articles on editors the historical Jesus, Christian origins, and Nina E. Livesey related fields. University of Oklahoma Manuscripts may be submitted to the publisher, Polebridge Press, Willamette University, Salem Clayton N. Jefford Oregon 97301; 503-375-5323; fax 503-375-5324; Saint Meinrad Seminary and [email protected]. A style guide is School of Theology available from Polebridge Press. Please note that all manuscripts must be double-spaced, and editorial board accompanied by a matching electronic copy. Arthur J. Dewey Subscription Information: The annual Forum Xavier University subscription rate is $30. Back issues may be Robert T. Fortna ordered from the publisher. Direct all inquiries Vassar College, Emeritus concerning subscriptions, memberships, and permissions to Polebridge Press, Willamette Julian V. Hills University, Salem Oregon 97301; 503-375-5323; Marquette University fax 503-375-5324. Roy W. Hoover Copyright © 2014 by Polebridge Press, Inc. Whitman College, Emeritus All rights reserved. The contents of this publication cannot be reproduced either in Lane C. -

Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth's Epistle to the Romans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University B. R. Lakin School of Religion Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth’s Epistle to the Romans Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MARS Degree: Area of Specialization: Philosophical Theology By Sean Turchin June 20, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1. IN THE WAKE OF KANTIANISM: ESTABLISHING THE THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THOUGHT WHEREIN ROMANS II WAS INTRODUCED Barth and Kantianism p.7 Barth and Schleiermacherianism p.14 Barth and Ritschlianism p.17 Barth and Herrmannianism p. 20 Barth and neo-Kantianism p. 30 Reactionary Theology: The Relationship of Barth’s Römerbrief to His Early Theology p. 39 1. Breaking with Liberalism: Immanentism and Social Ethics p. 39 2. Dropping the “Bomb”: The Publication of Romans I p. 43 Chapter 2. EXAMINING THE REFORMULATION OF ROMANS I AND THE PUBLICATION OF ROMANS II The Need and Tools for Reformulation p. 47 The Theme of Romans II p. 51 Chapter 3. KIERKEGAARD OR NEO-KANTIANISM: CORRELATING THEMES AND INFLUENCES WITHIN ROMANS II The Kierkegaard Reception in Late 19th and 20th Century Germany p. 55 The Infinite Qualitative Distinction p. 59 1. Dialectic of Time and Eternity p. 61 2. Urgeschichte and Christianity p. 64 3. The Dialectic of Christ and Adam p. 75 Knowledge of God p. 79 1. Idea or Reality: Barth and the neo-Kantian conception of Ursprung p. 79 2. Paradox: The Dialectic of Veiling and Unveiling p. -

Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth's

Liberty University B. R. Lakin School of Religion Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth’s Epistle to the Romans Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MARS Degree: Area of Specialization: Philosophical Theology By Sean Turchin June 20, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1. IN THE WAKE OF KANTIANISM: ESTABLISHING THE THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THOUGHT WHEREIN ROMANS II WAS INTRODUCED Barth and Kantianism p.7 Barth and Schleiermacherianism p.14 Barth and Ritschlianism p.17 Barth and Herrmannianism p. 20 Barth and neo-Kantianism p. 30 Reactionary Theology: The Relationship of Barth’s Römerbrief to His Early Theology p. 39 1. Breaking with Liberalism: Immanentism and Social Ethics p. 39 2. Dropping the “Bomb”: The Publication of Romans I p. 43 Chapter 2. EXAMINING THE REFORMULATION OF ROMANS I AND THE PUBLICATION OF ROMANS II The Need and Tools for Reformulation p. 47 The Theme of Romans II p. 51 Chapter 3. KIERKEGAARD OR NEO-KANTIANISM: CORRELATING THEMES AND INFLUENCES WITHIN ROMANS II The Kierkegaard Reception in Late 19th and 20th Century Germany p. 55 The Infinite Qualitative Distinction p. 59 1. Dialectic of Time and Eternity p. 61 2. Urgeschichte and Christianity p. 64 3. The Dialectic of Christ and Adam p. 75 Knowledge of God p. 79 1. Idea or Reality: Barth and the neo-Kantian conception of Ursprung p. 79 2. Paradox: The Dialectic of Veiling and Unveiling p. 83 3. Faith and Offense p. 87 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS p. 88 BIBLIOGRAPHY p. 90 ii INTRODUCTION When Karl Barth first introduced the second edition of his Epistle to the Romans in 1921, theologian Karl Adams said it was “the bomb that fell on the playground of the theologians.”1 The bombing ground upon which Barth’s powerful, programmatic exposition fell was a theological landscape that had never emerged from the philosophical effects of Immanuel Kant’s pervasive epistemological dualism. -

JOHN Mcconnachie AS the ORIGINAL ADVOCATE of the THEOLOGY of KARL BARTH in SCOTLAND: the PRIMACY of REVELATION JOHN MCPAKE, BORTIIWICK, EAST LOTHIAN

JOHN McCONNACHIE AS THE ORIGINAL ADVOCATE OF THE THEOLOGY OF KARL BARTH IN SCOTLAND: THE PRIMACY OF REVELATION JOHN MCPAKE, BORTIIWICK, EAST LOTHIAN Students of Scottish church history and theology are now immeasurably indebted to the editors of the Dictionary of Scottish Church History curl Theology 1 for their considerable labour in bringing such a near comprehensive guide into their possession. However, one or two names worthy of note have inevitably escaped attention. I wish to highlight one such, John McConnachie, whom I judge worthy of inclusion. For McConnachie might reasonably be regarded as the original advocate of the theology of Karl Barth in Scotland. If this claim can be proven, McConnachie surely deserves a place in any account of the course of Scottish theology in the first half of the twentieth century. This article seeks to justify the contention that McConnachie has earned the right to such a title, and, in particular, to focus upon what I take to be his central concern, the primacy of revelation in Barth's theology. Introduction John McConnachie was born at Fochabers, Moray, on October 13, 1875. He graduated M.A. from the University of Aberdeen in 1896, before proceeding to study Divinity at New College, Edinburgh. Here McConnachie gained a prestigious Cunningham Fellowship in 1900,2 enabling him to study in Germany under Wilhelm Herrmann at the University of Marburg. In so doing, McConnachie stood in line with such theologians as H.R. Mackintosh, D.S. Cairns, John Baillie and Donald Baillie who had made a similar journey in their own day. -

A Comparative Study Between Machen and Mcintire Concerning Their View of the Church As Related to Their Influence on the Presbyterian Church in Korea

A COMPARATIVE STUDY BETWEEN MACHEN AND MCINTIRE CONCERNING THEIR VIEW OF THE CHURCH AS RELATED TO THEIR INFLUENCE ON THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN KOREA Submitted as part of the requirements for the degree of PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in the Faculty of Theology © University of Pretoria J. Gresham Machen provided the fundamentalist movement with intellectual leadership by writing several important books including Christianity and Liberalism (1923), the thesis of which is that Christianity and liberalism are entirely different religions because of their different assumptions. He has striven to reform within the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America(PCUSA). He founded Westminster Theological Seminary in 1929 and formed the Independent Board for the PreSb)1erian Foreign Missions. He contended that the PCUSA had to be a confessional church and require its teaching officers to subscribe to the Westminster Standards. Carl McIntire was an admirer of Machen, and he joined the fight against liberalism. But they were driven from the PCUSA after their effort to reform the church over the issue of apostasy. They formed the Presbyterian Church of America(PCA). Yet within less than a year after the PCA was formed, in June of 1937, itwas divided. There were the differences of opinion between Machen and McIntire during the period from early 1936 to January I, 1937, when Machen died. And these differences primarily focused on the three distinct issues that represented also the differences between the majority and the minority of the PCA that would become later the Orthodox Presbyterian Church(OPC) and the Bible Presbyterian Church(BPC), respectively: dispensational ism, Christian liberty, and church polity. -

Karl Barth on Pietism and the Theology of the Reformation

HOLINESS THE JOURNAL OF WESLEY HOUSE CAMBRIDGE What has Basel to do with Epworth? Karl Barth on Pietism and the theology of the Reformation David Gilland DR DAVID ANDREW GILLAND is Lecture r i n Systemat ic Theolo gy at t he Seminar für Evangelische Theologie und Relig ionspä dagogik a t the Technical University of Braunschweig, Ge rman y. H e i s a J oh n W e s ley Fell o w and a Fellow of The Center for Barth Studies at Princeton Theological Seminar y. [email protected] Braunschweig, Germany This article examines Karl Barth’s earliest engagements with Pietism, rationalism and liberal Protestantism against the backdrop of the theologies of Albrecht Ritschl and Wilhelm Herrmann. The analysis then follows Barth through his rejection of liberal theology and his development of a dialectical theology over against Wilhelm Herrmann and with particular reference to Martin Luther’s theologia crucis . The article concludes by examining Barth’s comments on religious experience to a group of Methodist pastors in Switzerland in 1961. KARL BARTH • DIALECTICAL THEOLOGY • PIETISM • RATIONALISM • LIBERAL PROTESTANTISM • METHODISM • ALBRECHT RITSCHL • WILLHELM HERRMANN • RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE • CROSS www.wesley.cam.ac.uk/holiness ISSN 2058-5969 HOLINESS The Journal of Wesley House Cambridge Copyright © Author Volume 3 (2017) Issue 2 (Holiness & Reformation): pp. 191 –206 David Gilland Introduction Karl Barth (1886–1968) and Methodism might at first appear to be an unusual topic, evoking clichés along the lines of ‘What does Basel have to do with Epworth?’ or similar. The reasons for this are legion. First, in what is generally understood to be Barth’s sweeping rejection of the liberal theology of Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), Barth is also often understood to have done away altogether with religious experience, one of the central components of Methodist belief and practice.