'Thy Word Is All' : Karl Barth's University Exegetical Lectures, 1921-1928

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Study of the Fundamentals of Martin Luther's Theology in The

The Study of the Fundamentals of Martin Luther’s Theology in the Light of Ecumenism 1 Tuomo Mannermaa Translated and edited by Kirsi Stjerna It is not unusual in the history of academic disciplines that new ideas concerning the fundamentals of a particular discipline emerge either by accident or as a result of impulses from another field of scholarship. This is the case also in today’s Luther research. Two particular fields can be named from most recent history, fields with significant impulses for new insights: ecumenism and philosophy. The philosophical impulses are connected with the task of locating Luther’s theology in regard to both scholasticism, which preceded Luther, and the philosophy of the modern times, which succeeded him. Ecumenism presents its own challenges for Luther research and Lutheran theological tradition. It is the latter issue that I wish to address here, touching upon the issues related to philosophy only as far as it is helpful in light of ecumenical questions at stake. The ecumenical impulses originate, above all, from two sources: Lutheran–Orthodox theological discussions, on the one hand, and Lutheran–Catholic theological encounters, on the other. The challenge issued to Luther research by Lutheran–Orthodox discussions lies in the theme “Luther and the doctrine of divinization,” whereas Lutheran–Catholic cooperation in Luther research has set out to clarify the theme, “Luther as a theologian of love.” Especially the late Catholic Luther specialist Peter Manns has unraveled the latter topic wit h his fruitful Luther interpretation. The first of these two topics, “Luther and theosis (divinization),” is fundamental in the sense that it gives expression to the patristic standard of comparison that all these three denominations share and that can serve as a starting point in their process toward a common understanding. -

A Philosophical Audacity

A Philosophical Audacity Barth’s Notion of Experience Between Neo-Kantianism and Nietzsche1 Anthony Feneuil [email protected] This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: “A Philosophical Audacity: Barth’s Notion of Experience Between Neo-Kantianism and Nietzsche“, which has been published in final form at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ijst.12077/full. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving Abstract: This article addresses Barth’s dialectical notion of experience in the 1920s. I argue that the theoretical problem raised by recent studies on Barth’s notion of experience after his break with liberalism (i.e., the apparent inconsistency between Barth’s move towards an increasingly neo-Kantian understanding of experience and his emphasis on the existential and psychological dimensions of experience) can be solved by the hypothesis of a Nietzschean influence on Barth's epistemology in the 1920s. I defend not only the historical plausibility but also the conceptual fecundity of such a hypothesis, which casts a new light on Barth’s relation to philosophy and the notion of experience, and lays the basis for a consistent Barthian theology of experience. *** Theology is not a discreet slice of knowledge you could simply add to one philosophy or other. It exists nowhere but through philosophy, and that is why Barth’s theological innovation cannot manifest itself apart from philosophical innovation. Barth is not a philosopher, and he does not explicitly develop his concepts in a philosophical way. But Barth repeatedly claims we cannot grant theology an extraordinary status among human discourses. -

Christianity and Liberalism

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Christianity and Liberalism EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:19 PM 1 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:19 PM 2 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Christianity and Liberalism J. Gresham Machen, D.D. New Edition William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan / Cambridge, U.K. EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:19 PM 3 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen First published 1923 New edition published 2009 by Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. All rights reserved Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 / P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K. Printed in the United States of America 15141312111009 7654321 ISBN 978-0-8028-6499-4 ISBN 978-0-8028-6488-8 (Westminster Edition) www.eerdmans.com EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:20 PM 4 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen To My Mother EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:20 PM 5 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen EERDMANS -- Christianity and Liberalism New Edition (Machen) final text Tuesday, March 31, 2009 12:33:20 PM 6 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Contents - Foreword, by Carl R. Trueman ix Acknowledgments xvi Preface xvii I. Introduction 1 II. Doctrine 15 III. -

Religious Apriori

Religious Apriori 2 ANDERS NYGREN’s Religious Apriori with an Introduction by Walter H. Capps Edited by Walter H. Capps & Kjell O. Lejon Linköping Studies in Religion and Religious Education, No 2 LINKÖPING UNIVERSITY ELECTRONIC PRESS 2000 3 The publishers will keep this document on-line on the Internet (or its possible replacement network in the future) for a period of 25 years from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances as described separately. The on-line availability of the document implies a permanent permission for anyone to read, to print out single copies and to use it unchanged for any non-commercial research and educational purpose. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional on the consent of the copyright owner. The publication also includes production of a number of copies on paper archived in Swedish university libraries and by the copyrightholder/s. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure that the on-line version will be permanently accessible and unchanged at least until the expiration of the publication period. For additional information about the Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its WWW home page: http://www.ep.liu.se Linköping Studies in Religion and Religious Education, No 2 Series editor: Edgar Almén Linköping University Electronic Press Linköping, Sweden, 2000 ISBN 91-7219-640-8 (print) ISSN 1404-3971 (print) www.ep.liu.se/ea/rel/2000/002/ (WWW) ISSN 1404-4269 (online) Printed by: UniTryck, Linköping 2000 Kjell O. -

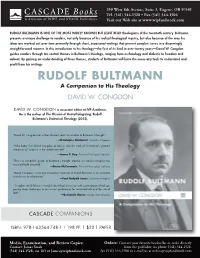

RUDOLF BULTMANN IS ONE of the MOST WIDELY KNOWN but LEAST READ Theologians of the Twentieth Century

199 West 8th Avenue, Suite 3, Eugene, OR 97401 CASCADE Books Tel. (541) 344-1528 • Fax (541) 344-1506 A division of WIPF and STOCK Publishers Visit our Web site at www.wipfandstock.com RUDOLF BULTMANN IS ONE OF THE MOST WIDELY KNOWN BUT LEAST READ theologians of the twentieth century. Bultmann presents a unique challenge to readers, not only because of his radical theological inquiry, but also because of the way his ideas are worked out over time primarily through short, occasional writings that present complex issues in a disarmingly straightforward manner. In this introduction to his theology—the first of its kind in over twenty years—David W. Congdon guides readers through ten central themes in Bultmann’s theology, ranging from eschatology and dialectic to freedom and advent. By gaining an understanding of these themes, students of Bultmann will have the necessary tools to understand and profit from his writings. RUDOLF BULTMANN A Companion to His Theology DAVID W. CONGDON DAVID W. CONGDON is associate editor at IVP Academic. He is the author of The Mission of Demythologizing: Rudolf Bultmann’s Dialectical Theology (2015). “David W. Congdon has written the best short introduction to Bultmann’s thought.” —Christophe Chalamet, University of Geneva “Who better than David Congdon to take us into the work of Christianity’s greatest interpreter of Scripture in the modern period?” —James F. Kay, Princeton Theological Seminary “This is a wonderful ‘guide’ to Bultmann’s thought. Indeed, it is hard to imagine one more perfectly executed.” —Bruce McCormack, Princeton Theological Seminary “David Congdon’s lucid and innovative treatment of Rudolf Bultmann is an excellent contribution to scholarship.” —Paul Dafydd Jones, University of Virginia “Congdon sets Bultmann’s thought into critical discussion with contemporary theology, posing sharp challenges to our current preferences for ressourcement and the rule of faith.” —Benjamin Myers, Charles Sturt University CASCADE COMPANIONS ISBN: 978-1-62564-748-1 | 198 PP. -

A Christian Neo-Confucian Dialogue by Contrasting the Anthropological Views of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong for the Development of Chinese Theological Anthropology

Contrast the Differences: A Christian Neo-Confucian Dialogue By Contrasting the Anthropological Views of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong For the Development of Chinese Theological Anthropology By CHAN, Hoi Yan A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Knox College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Theology awarded by Knox College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by CHAN, Hoi Yan 2012 Contrast the Differences: A Christian Neo-Confucian Dialogue By Contrasting the Anthropological Views of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong For the Development of Chinese Theological Anthropology CHAN, Hoi Yan Doctor of Theology, 2012 Knox College, University of Toronto Abstract The thesis employs the method of contrast of a Chinese scholar Vincent Shen to compare and contrast the anthropologies of Karl Barth and Shili Xiong, with the goal of achieving a constructive inner dialogue made explicit for the development of a contextual Chinese theological anthropology. When the anthropologies of Barth and Xiong are put side by side for contrast, their views are clearly different from each other. However, in the inner dialogue, it is found that the perspectives of Barth and Xiong are not absolutely contradictory. It appears that Barth and Xiong shared several similarities in their observations of some phenomena of humanity, though they adopted different perspectives to interpret these phenomena. As Barth and Xiong are so different from each other on their cultural and academic backgrounds, it is interesting that they do come to similar observation on the phenomena of humanity, yet it is also argued that parallels should not be easily drawn. -

Dogma and History in Victorian Scotland

Dogma and History in Victorian Scotland Todd Regan Statham Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University Montreal, Quebec February 2011 A Thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Todd Regan Statham Table of Contents Abstract v Résumé vii Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations x Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The Scottish Presbyterian Church ‘in’ History 18 1.1. Introduction 18 1.2. Church, Scripture, and Tradition 19 1.2.1. Scripture and Tradition in Roman Catholicism 20 1.2.2. Scripture and Tradition in Protestantism 22 1.2.3. A Development of Dogma? 24 1.3. Church, Doctrine, and History 27 1.3.1. Historical Criticism of Doctrine in the Reformation 29 1.3.2. Historical Criticism of Doctrine in the Enlightenment 32 1.3.3. Historical Criticism of Doctrine in Romanticism and Idealism 35 1.4. Church: Scottish and Reformed 42 1.4.1. The Scottish Church and the Continent 42 1.4.2. Westminster Calvinism 44 1.4.3. The Evangelical Revival 48 1.4.4. Enlightened Legacies 53 1.4.5. Romantic Legacies 56 1.4.6. The Free Church and the United Presbyterians in Victorian Scotland 61 1.5. Conclusion 65 Chapter 2: William Cunningham, John Henry Newman, and the Development of Doctrine 67 2.1. Introduction 67 2.2. William Cunningham 69 2.3. An Essay on the Development of Doctrine 72 2.3.1. Against “Bible Religion” and the Church Invisible 74 2.3.2. Cunningham on Scripture and Church 78 2.3.3. The Theory of Development 82 ii 2.3.4. -

Reflections on Konrad Hammann's Biography of Rudolf Bultmann

Reflections on Konrad Hammann’s Biography of Rudolf Bultmann—with Implications for Christology Philip Devenish Having translated Konrad Hammann’s biography of Rudolf Bultmann into English, I reckon that in its ferreting out and mining of the sources it is almost— if not quite—beyond praise. And yet, a biography of Rudolf Bultmann . what an odd idea, if also upon reflection what an instructive one, and for christology in particular! Consider: In 1926, introducing his Jesus in the series Die Unsterblichen (“The Immortals”), Bultmann wrote: Even if there might be good reasons for being interested in the personality of significant historical figures, be it Plato or Jesus, Dante or Luther, Napoleon or Goethe, it is still the case that this interest does not touch what mattered to these persons. For their interest was not in their personality, but rather in their work. And in fact not even in their work, insofar as that is “understandable” as an expression of their personality, or insofar as in the work the personality “took shape,” but rather insofar as their work is a cause (Sache) to which they committed themselves.1 True, Bultmann does not say that there are not “good reasons for being interested in the personality of significant historical figures,” even if this were not what mattered to them. All the same, Hammann does give numerous and, I find, convincing reasons for holding not only that Bultmann was not interested in revealing his own “personality,” but even that he had an aversion to such an interest. Thus, not only did he not respond to both personal and public en- treaties from Karl Jaspers to do so, as well as persistently to decline to make a public confession of his own faith, but—and in this like his father—he also even explicitly refused to permit a sermon at his own funeral, seemingly sensing that eulogizing was, like sin, “lurking at the door” (Gen 4:6). -

Karl Barth's Social Philosophy, 1918 -1933

KARL BARTH'S SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY, 1918 -1933 Peter John Holmes Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Divinity University of Glasgow June 2001 The enterprise of theological ethics is not one with which to trifle. It must be taken up properly - and this can mean only on the assumption that the command of the grace of God is its sole content - or it is better left alone. ' Karl Barth, Chin-ch Dogmatics 11/2p. 533. ii ABSTRACT This thesis is a contribution to the contemporary reassessment of Karl Barth's social philosophy. A close reading of the English translation of the text of a series of posthumously published lectures on ethics which Barth gave in the universities of Münster and Bonn between 1929 and 1933 is the basis of the work. Previous literature includes no discussion of the lectures. The thesis argues that the lectures show the foundation of Barth's thinking both of theology as a science and of ethics as a part of dogmatics, and that his subsequent work developed these ideas. Barth's intellectual debt to Hegel is recognised by showing that he returns to the fundamental theological questions of the relationship between faith and reason, and truth and method in the form in which Hegel discussed them at the end of the nineteenth century. The thesis acknowledges the influence of Barth's helper, Charlotte von Kirschbaum, and contrary to other opinions claims that the impact of Wilhelm Herrmann's thinking on Barth remained until 1933. -

Assessing the Work of Rudolf Bultmann

Foundations and Facets FORUM third series 3,2 fall 2014 Assessing the work of Rudolf Bultmann lane c. mcgaughy Preface 5 schubert m. ogden The Legacy of Rudolf Bultmann and the Ideal of a Fully Critical Theology 9 philip devenish Reflections on Konrad Hammann’s Biography of Rudolf Bultmann—with Implications for Christology 21 william o. walker, jr. Demythologizing and Christology 31 gerd lüdemann Kêrygma and History in the Thought of Rudolf Bultmann 45 jon f. dechow The ‘Gospel’ and the Emperor Cult From Bultmann to Crossan 63 publisher Forum, a biannual journal first published in Polebridge Press 1985, contains current research in biblical and cognate studies. The journal features articles on editors the historical Jesus, Christian origins, and Nina E. Livesey related fields. University of Oklahoma Manuscripts may be submitted to the publisher, Polebridge Press, Willamette University, Salem Clayton N. Jefford Oregon 97301; 503-375-5323; fax 503-375-5324; Saint Meinrad Seminary and [email protected]. A style guide is School of Theology available from Polebridge Press. Please note that all manuscripts must be double-spaced, and editorial board accompanied by a matching electronic copy. Arthur J. Dewey Subscription Information: The annual Forum Xavier University subscription rate is $30. Back issues may be Robert T. Fortna ordered from the publisher. Direct all inquiries Vassar College, Emeritus concerning subscriptions, memberships, and permissions to Polebridge Press, Willamette Julian V. Hills University, Salem Oregon 97301; 503-375-5323; Marquette University fax 503-375-5324. Roy W. Hoover Copyright © 2014 by Polebridge Press, Inc. Whitman College, Emeritus All rights reserved. The contents of this publication cannot be reproduced either in Lane C. -

Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth's Epistle to the Romans

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Liberty University Digital Commons Liberty University B. R. Lakin School of Religion Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth’s Epistle to the Romans Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MARS Degree: Area of Specialization: Philosophical Theology By Sean Turchin June 20, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1. IN THE WAKE OF KANTIANISM: ESTABLISHING THE THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THOUGHT WHEREIN ROMANS II WAS INTRODUCED Barth and Kantianism p.7 Barth and Schleiermacherianism p.14 Barth and Ritschlianism p.17 Barth and Herrmannianism p. 20 Barth and neo-Kantianism p. 30 Reactionary Theology: The Relationship of Barth’s Römerbrief to His Early Theology p. 39 1. Breaking with Liberalism: Immanentism and Social Ethics p. 39 2. Dropping the “Bomb”: The Publication of Romans I p. 43 Chapter 2. EXAMINING THE REFORMULATION OF ROMANS I AND THE PUBLICATION OF ROMANS II The Need and Tools for Reformulation p. 47 The Theme of Romans II p. 51 Chapter 3. KIERKEGAARD OR NEO-KANTIANISM: CORRELATING THEMES AND INFLUENCES WITHIN ROMANS II The Kierkegaard Reception in Late 19th and 20th Century Germany p. 55 The Infinite Qualitative Distinction p. 59 1. Dialectic of Time and Eternity p. 61 2. Urgeschichte and Christianity p. 64 3. The Dialectic of Christ and Adam p. 75 Knowledge of God p. 79 1. Idea or Reality: Barth and the neo-Kantian conception of Ursprung p. 79 2. Paradox: The Dialectic of Veiling and Unveiling p. -

Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth's

Liberty University B. R. Lakin School of Religion Examining the Primary Influence on Karl Barth’s Epistle to the Romans Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the MARS Degree: Area of Specialization: Philosophical Theology By Sean Turchin June 20, 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1. IN THE WAKE OF KANTIANISM: ESTABLISHING THE THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT OF 19TH AND 20TH CENTURY THOUGHT WHEREIN ROMANS II WAS INTRODUCED Barth and Kantianism p.7 Barth and Schleiermacherianism p.14 Barth and Ritschlianism p.17 Barth and Herrmannianism p. 20 Barth and neo-Kantianism p. 30 Reactionary Theology: The Relationship of Barth’s Römerbrief to His Early Theology p. 39 1. Breaking with Liberalism: Immanentism and Social Ethics p. 39 2. Dropping the “Bomb”: The Publication of Romans I p. 43 Chapter 2. EXAMINING THE REFORMULATION OF ROMANS I AND THE PUBLICATION OF ROMANS II The Need and Tools for Reformulation p. 47 The Theme of Romans II p. 51 Chapter 3. KIERKEGAARD OR NEO-KANTIANISM: CORRELATING THEMES AND INFLUENCES WITHIN ROMANS II The Kierkegaard Reception in Late 19th and 20th Century Germany p. 55 The Infinite Qualitative Distinction p. 59 1. Dialectic of Time and Eternity p. 61 2. Urgeschichte and Christianity p. 64 3. The Dialectic of Christ and Adam p. 75 Knowledge of God p. 79 1. Idea or Reality: Barth and the neo-Kantian conception of Ursprung p. 79 2. Paradox: The Dialectic of Veiling and Unveiling p. 83 3. Faith and Offense p. 87 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS p. 88 BIBLIOGRAPHY p. 90 ii INTRODUCTION When Karl Barth first introduced the second edition of his Epistle to the Romans in 1921, theologian Karl Adams said it was “the bomb that fell on the playground of the theologians.”1 The bombing ground upon which Barth’s powerful, programmatic exposition fell was a theological landscape that had never emerged from the philosophical effects of Immanuel Kant’s pervasive epistemological dualism.