116 the Criminal Enforcement of Antitrust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early American Civilizations

grade 1 Core Knowledge Language Arts® • Listening & Learning™ Strand Early American Civilizations American Early Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Read-Aloud Again!™ It Tell Early American Civilizations Tell It Again!™ Read-Aloud Anthology Listening & Learning™ Strand GrAdE 1 Core Knowledge Language Arts® Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. You are free: to Share — to copy, distribute and transmit the work to Remix — to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike — If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to this web page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Copyright © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation www.coreknowledge.org All Rights Reserved. Core Knowledge Language Arts, Listening & Learning, and Tell It Again are trademarks of the Core Knowledge Foundation. Trademarks and trade names are shown in this book strictly for illustrative and educational purposes and are the property of their respective owners. -

The Christmas Jethro Tull

THE CHRISTMAS JETHRO TULL It must be a decade ago that we started playing benefit concerts in churches and cathedrals during Advent. And I hope you find that we merry men have prepared a tasty aperitif of seasonal tunes and Tulloid classics to whet your appetite for the Christmas feast. It was at Lincoln – the tenth great church we'd played like this, if memory serves – that I was asked why we do it. And my first answer was and remains that the main thing is to encourage you all to dig just a little further into that hard-pressed Christmas trouser pocket to support your local cathedral. Look around you. Beautiful isn't it? But it costs the earth to keep it standing here - and the world has changed a bit since those medieval or Victorian master-masons and labourers put it together, so we're not going to be building any more of them. Seems to me that a couple of fund-raiser gigs between schlepping around the world on tour and going home to hang up our stockings is a worthwhile thing to do. And please be assured we're not taking a Yuletide dram off you. The proceeds from ticket sales – tickets you've been kind enough to buy to join us at this concert – go to support the fabric and running costs of this lovely cathedral. A big thankyou from me, then, for supporting us in supporting your local spiritual asset. So our first reason is largely architectural. But there are a couple of other reasons. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Zde P0vodni Duch Nechybi.Z Mnoha Anderso- Nem & Spol

'ETHRO TULUS IAN ANDERS NN Y GERALDABOSTO rToCKA TEXT PETRNOZIEKA FOTO EMI Druhd a dalit d{Iyjsou bdi,ndv literatufe.Ve fiImovd brani,i vdtiinou zdleZf na rtspdchupfivodniho. Pokraiovdni pievdind nestojiza moc,ale existujedost ,,dvojek"A ,,trojek",kterd se zdafily. Zaviechny jmenujme Coppolovy Kmotry. hudbd, zejm|na rockov6,to v5akneni dit matkuv$ech koncepdnich alb"; pozddji se nechal A tak n6m postupndnabizi Geralda hrabivdho vribecobvykl6. P6r nepiili$ vyznam- sly5et,Ze se jednalo o parodie. a bezskrupuli jednajiciho bankdie (vdddnd pisefi nich vijimek senajde, ale vdt$inou Fanou5cije v5akuvitali aThick As A Bricki A Pas- BankerBets, Banker Wins), Geralda bezdomovce, jde jen o vnrZiti nilzvtt a velmi volnd sionPlay patii k nejoblibendj$imtitultm JT.Brit- kterf byl v ddtstvi zneuLitydom6cim a jako zmdk- f spojeni.Zakladatel |ethro Tull Ian skdkritika byla nrihlemnohem chladndj$i.,,Myslel dileca teplou5otcem vyhozen z domu,Geralda AndersonvZdv y zkou5el mdnit zavedenezaveden|, obydeje,obvdeie. jsem, Zejsme do td miry dok|zali namichatjakous- voj6kahynouciho kdesiv Asii, Geraldasboristu dastos velmi slu$nfmi vfsledky. Nyni sevrdtil no- takousvdrohodnost s riplnfmi blbostmi, abyvdt$ina zapdlendhopro cirkev.A nakonecprachobydejn6ho vfm pohledemk jednomu z nejslavndj$ichalb svd lidi pochopila,Ze jde o vtip. Z dne$nihopohledu to muLez mal6hoobchfidku, i:ijiciho SedyZivot vbez- karidry a uspdl. byla nesporndhloupost, ndkdo by snadiekl pond- ddtndmmanielstvi. |edinfm potd5enimmu je hra- kud pubertdlni,na to alemohu namitnout,Ze jsem ni si s modely Leleznic. ThickAs A Brick byl opoZddnfve vyvinu a bylo mi tenkr6t teprve elovdk by oiek6val,2e bude zahrnut variacemina dtyiiadvacet,tal<i,e to tehdy byl hlas a mozek mla- origin6l.Neni to rozs6hl6rockov6 suita, celek je roz- Letospdta5edes6tilet'i Anderson se hudbd coby diika, ktery sepokou5el uddlat ndco jinak," iekl ddlenna devdtkapitol, pdt probird moZndpromdny zdroji obZivyvdnovat nemusi. -

In Piazza Della Loggia

BRESCIA - PIAZZA LOGGIA GIOVEDI 17 LUGLIO 2014 – ORE 21,30 SONICS in ”MERAVIGLIA” Spettacolo di performers volanti creato e diretto da : Alessandro Pietrolini Acrobazie aeree mozzafiato, macchine sceniche imponenti raccontano la storia di come ognuno di noi spesso si affidi a pozioni magiche o a falsi santi per affrontare il quotidiano dimenticando che l’unico vero “elisir” della vita risiede dentro noi stessi e nella capacità di emozionarci di fronte alle cose semplici. “Se solo imparassimo a scollegarci dalla realtà...”ognuno di noi avrebbe dentro di sé il suo pianeta Meraviglia, il luogo in cui contenere l'emozione non convenzionale, il luogo in cui rifugiarsi quando quello che ci sta intorno sbiadisce i contorni del nostro essere. Adrenalina e stupore sono gli ingredienti di questa favola moderna e senza presunzione se non quella di trasportare lo spettatore negli spazi surreali e indefiniti della fantasia umana, luoghi animati da animali e fiori anomali, in cui una carezza si trasforma in una straordinaria storia d’amore sospesa per aria. "Meraviglia" è uno dei grandi spettacoli a cui ha dato vita la creatività di Alessandro Pietrolini, fondatore insieme ad Ileana Prudente dei SONICS, una compagnia di acrobati tutta italiana protagonista di grandi eventi mediatici in Italia e all'estero. Biglietti: in prevendita : 1° settore numerato € 23,00 – 2° settore NON numerato € 18,00 sera dello spettacolo : 1° settore numerato € 25,00 – 2° settore non numerato € 20,00 SABATO 19 LUGLIO 2014 – ORE 21,30 JETHRO TULL’s IAN ANDERSON ppplaysplays THE BEST OF TULL AND NEW ALBUM HOMO ERRATICUS Dopo il successo del 40th anniversary tour di Thick as a Brick 1 & 2 Torna a Brescia Ian Anderson col nuovo doppio show IAN ANDERSON , leader indiscusso dei JETHRO TULL , ritorna in tour col suo nuovo concept album “HOMO ERRATICUS” (Audioglobe), appena uscito. -

I Jethro Tull Al Politeama Rossetti Di Trieste: Un Tuffo Nei “Sixties” Con Il “50Th Anniversary Tour”

I Jethro Tull al Politeama Rossetti di Trieste: Un tuffo nei “sixties” con il “50th Anniversary Tour” La psichedelia di Ian Anderson ha invaso il Teatro Politeama Rossetti di Trieste con il concerto celebrativo per i 50 anni dei Jethro Tull, la band progressive rock inglese nota in tutto il mondo per il carisma del leader e per il suono inconfondibile del suo flauto traverso presente in buona parte dei brani dei Jethro Tull. (foto Dario Furlan) Numerose nel corso degli anni le “incursioni” di Ian Anderson (con o senza i Jethro Tull) in Italia e ogni volta i suoi spettacoli sono stati presi d’assalto dai fan tant’è che anche in questa occasione l’evento, organizzato daBPM Concerti quale ultimo di quattro date in Italia, ha registrato il sold out riempiendo in ogni ordine di posti la splendida struttura del Politeama Rossetti . Fan inglesi si scattano un selfie a ricordo dell’evento con il manifesto del concerto alle spalle (foto Dario Furlan) Le prime note del concerto, aperto da My Sunday Feeling (dal primo album This Was), hanno immediatamente trasportato gli spettatori nei “sixties”, gli anni in cui i Jethro Tull hanno preso vita, con un caleidoscopio di colori cangianti e ruotanti in continuazione sul palco accompagnati dalle sonorità tipiche delle strumentazioni di quel periodo e da filmati attinenti alla discografia del gruppo proiettati sul mega schermo alle spalle del palco: un viaggio nel tempo proseguito per tutta la durata dello spettacolo. Il palco (foto Dario Furlan) Per questa lunghissima tournée celebrativa dell’uscita di This Was Ian Anderson ha voluto con sé sul palco Florian Opahle (chitarra), John O’Hara (tastiere), David Goodier (basso) e Scott Hammond (batteria), degli autentici fuoriclasse che, complice anche la perfetta acustica del teatro, hanno contribuito a creare un sound compatto, energico e potente nelle parti più elettriche del concerto e melodioso e caldo in quelle acustiche. -

Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson, a Giugno Tour in Italia

MERCOLEDì 5 APRILE 2017 A 50 anni dalla nascita dei Jethro Tull e con un repertorio di brani leggendari, Ian Anderson torna in tour nel nostro Paese a giugno con un nuovo live: un concerto spettacolo dove l'esperienza del viaggio Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson, a musicale si fa vivida con le proiezioni in video HD a ricreare, più giugno tour in Italia fedelmente possibile, le indistinguibili atmosfere che hanno segnato l'incredibile avventura dei Jethro Tull. A 50 anni dalla nascita della band, la leggenda del rock progressive presenta il nuovo concerto Dopo il grande successo del lungo tour estivo in Italia nel 2016, la spettacolo leggenda del rock progressive, accompagnato dalla sua band, sarà in Italia per quattro date: il 22 giugno, a Pescara (Teatro Gabriele D'Annunzio); il 23, a Roma (Auditorium Parco della Musica, Sala Santa Cecilia); il 24, a Sogliano al Rubicone, FC (Piazza Matteotti); il 26 giugno a ANTONIO GALLUZZO Brescia (Piazza della Loggia). Sarà l'occasione per riascoltare il miglior repertorio dei Jethro Tull, Locomotive Breath, Aqualung, Living in the Past, Boureé, e molti altri, inclusi alcuni brani della produzione più recente, in un viaggio [email protected] musicale instancabile, che ha fatto tappa in più di 40 paesi del mondo, SPETTACOLINEWS.IT con 3.000 concerti e più di 65 milioni di dischi venduti. L'uomo che ha reso popolare il flauto nel rock, continua ad attrarre le platee di tutto il mondo, accompagnandole sui sentieri del suo lungo passato e del repertorio storico della band e del rock progressive di qualità. -

Featuring BRUNO MARS’ ERIC HERNANDEZ

SPECIAL ISSUE! WIN A ROLAND PRIZE PACKAGE WORTH MORE THAN $2,300! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE ALIVE AND KICKING! ON STAGE WITH THE WORLD’S BIGGEST ACTS Featuring BRUNO MARS’ ERIC HERNANDEZ Plus OCTOBER 2018 KENDRICK LAMAR’S BON JOVI’S DAMIAN MARLEY’S LAMB OF GOD’S TONY TICO COURTNEY CHRIS NICHOLS TORRES DIEDRICK ADLER + BREATHING LIFE INTO A RECORDING | PHOTOS FROM SLAYER’S FINAL WORLD TOUR 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 BECOME A BETTER DRUMMER, FASTER When you’re serious about drumming, you need a kit to match your ambition. The V-Drums TD-17 series lets your technique shine through, backed up with training tools to push you further. Combining a TD-50-class sound engine with newly developed pads results in an affordable electronic drum kit that’s authentically close to playing acoustic drums – accurately mirroring the physical movement, stick coordination and hand/foot control that every drummer needs. Meanwhile, an array of built-in coaching functions will track your technique, measure your progress and increase your motivation. Becoming a better drummer is still hard work, but the TD-17 can help you get there. TD-17 Series V-Drums www.roland.com ACTIVEGRIP. NOW AVAILABLE IN STEALTH MODE. Introducing ActiveGrip Clear, a drumstick that looks like every other, but with an extraordinary feature. With Promark’s heat-activated technology, ActiveGrip Clear works under the radar, getting tackier the more you heat up. So no matter the mounting pressure, you always know you can handle it. WWW.MAPEXDESIGNLAB.COM #BUILTFROMTHESOUNDUP ONE AND DONE: Audix packs are the all-in-one drum miking solution The Audix DP5A and DP7 professional drum and percussion microphone packs are expertly curated collections that are perfect for stage or studio. -

Making the Decision: What to Do When Faced with International Cartel Exposure

The 2010 Competition Law Spring Forum presented by The Canadian Bar Association’s National Competition Law Section and the Continuing Legal Education Committee MAKING THE DECISION: WHAT TO DO WHEN FACED WITH INTERNATIONAL CARTEL EXPOSURE DEVELOPMENTS IMPACTING THE DECISION IN 2010 By Gary R. Spratling & D. Jarrett Arp Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP San Francisco, CA • Washington, DC Toronto, Canada May 17, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction......................................................................................................................................2 II. The Decision: What To Do When Faced With International Cartel Exposure...............................4 A. Recognition Of And Adjustment To The Starting Point In The Risk Analysis...................................................................................................................................4 B. Assessment Of Evidence Of Possible Cartel Violation. .........................................................4 C. Projection Of Potential Exposure To Enforcement Authority Sanctions. ..............................5 D. Identification And Evaluation Of Opportunities To Avoid Or Mitigate Sanctions.................................................................................................................................5 E. Analysis Of Civil Litigation Costs..........................................................................................5 F. Integration Of The Foregoing Considerations. .......................................................................6 -

Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson to Perform at Four Winds New Buffalo on Saturday, June 30, 2018

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JETHRO TULL BY IAN ANDERSON TO PERFORM AT FOUR WINDS NEW BUFFALO ON SATURDAY, JUNE 30, 2018 Tickets go on sale Friday, November 17 NEW BUFFALO, Mich. – November 14, 2017 – The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians’ Four Winds® Casinos are pleased to announce Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson: The 50th Anniversary Tour will perform at Four Winds New Buffalo’s® Silver Creek® Event Center on Saturday, June 30, 2018 at 9 p.m. Hotel and dinner packages are available on the night of the concert. Tickets can be purchased beginning Friday, November 17 at 11 a.m. EST exclusively through Ticketmaster®, www.ticketmaster.com, or by calling (800) 745-3000. Ticket prices for the show start at $99 plus applicable fees. Four Winds New Buffalo will be offering hotel and dinner packages along with tickets to Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson. The Hard Rock option is available for $583 and includes two concert tickets, a one-night hotel stay on Saturday, June 30, 2018 and a $50 gift card to Hard Rock Cafe® Four Winds. The Copper Rock option is available for $683 and includes two tickets to the performance, a one-night hotel stay on Saturday, June 30, 2018 and a $150 gift card to Copper Rock Steak House®. All hotel and dinner packages must be purchased through Ticketmaster. Early in 1968, a group of British musicians joined together in Luton, a town north of London, to form Jethro Tull. They began playing in pubs and clubs throughout southern England, eventually landing a standing gig at London’s famous Marquee Club in Soho. -

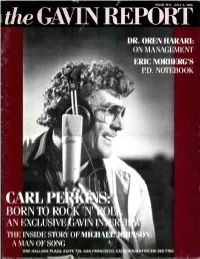

The GAVIN REPORT

ISSUE 1613 JULY 4, 1986 the GAVIN REPORT DR. OREN A RI: ON MANAGE ENT ERIC NORB 1RG'S PD. NOTE 00K BO N TO ROCK IN AN XCLUSIVE AVIN THE INSIDE STORY OF mtcuau A AN OF SONG s NE HALLIDIE PLAZA, SUITE 725, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA 94102 415-392.7750 www.americanradiohistory.com DEPECHE MODE "A Question Of Lust" From The Album Black Celebration DEPEC E su TE? HONEYMOON MODE? DON'T BE CONFUIED. THEY'RE BOTH eis HITS. HONEYMOON 11111E "What Does It Take" From The Album The Big Prize o 1986 Warner Bros. Records Inc. www.americanradiohistory.com the GAVIN REPORT Editor: Dave Sholin TOP 40 Station Reporting Phone (415)392 -7750 DOM Reports accepted Mondays at 8AM through 1 1 AM Wednesdays D e' Jet it M. 11Y.ie.Ca 6. 1. 1 . GENESIS - Invisible Touch (Atlantic) 4. 2. 2. El DeBarge - Who's Johnny (Gordy) G T 7. 4. 3. PETER GABRIEL - Sledgehammer (Geffen) 8. 6. 4. KENNY LOGGINS - Danger Zone (Columbia) 15. 10. 5. PETER CETERA - Glory Of Love (Full Moon/Warner Bros.) 11. 9. 6. ROD STEWART - Love Touch (Warner Bros.) 13. 8. 7. JANET JACKSON - Nasty (A &M) 1. 3. 8. Billy Ocean - There'll Be Sad Songs (Jive /Arista) 5. 5. 9. Simply Red - Holding Back The Years (Elektra) n G 21. 14. 10 . BILLY JOEL - Modern Woman (Epic) 2. 7. 11 . Howard Jones - No One Is To Blame (Elektra) 29. 12 . MADONNA - Papa Don't Preach (Sire/Warner Bros.) S 27. 21. 13. PET SHOP BOYS - Opportunities (EMI America) E 19. -

Das Finden Sie in Diesem Buch

DAS FINDEN SIE IN DIESEM BUCH DIE LOKOMOTIVE SCHNAUFTE UNTER TAGE 37 SCHLAGZEILEN DER 70ER JAHRE Tülls Auftritt im Salzbergwerk Merkers war für Veranstalter Selbst die Bravo fand Geschmack am Maskenball nach Andersons Art Michael Glotzbach das „Größte" AUCH SCHON MIST PRODUZIERT KLEINHOLZ IN DER JAHRHUNDERTHALLE Hamburg, Frankfurt, München: 1976 gab es nur drei deutsche Steine flogen und Scheiben splitterten beim allerersten Deutschlandkonzert Konzerte - und Kollegenschelte im Fachblatt-Interview DURCHGEDREHTER POP-PROFESSOR 4Q EIN KARTON VOLLER BÄNDER Ab Nürnberg als Quintett - und der „Rattenfänger" wird schon zum Etikett Die Aufnahmen für „Bursting Out" stammten von einem 8-Spur-Kassettenrecorder GAR NICHT REAKTIONÄR Clouds: Die Geburtshelfer des Prog-Rock wurden nie zu Giganten 41 HOPFEN UND MALZ VERLOREN Siegerländer lernte Tull auf einer Party kennen und lieben DIE POLIZEI ROCKTE MIT Der Film „Swing In" des Holländers Wim van der Linden wurde schon 1969 im Fernsehen gezeigt 42 LANGE GENUG BÖSE 1977 präsentierte sich Anderson mit neuem Aussehen und zivilisierter Kleidung „HALB OHNMÄCHTIG" Beliebt wie die Beatles und die Rolling Stones 4g KEIN ARMER MANN CLUB-AUSGABE KOSTET RICHTIG GELD lan Anderson und das Musikgeschäft: „Ich war nie von Ausbeutern umgeben" 500 Euro: Einige deutsche Vinyl-Ausgaben sind heute noch heiße Renner bei Ebay-Auktionen 4g SEX PISTOLS UND STRANGLERS FASZINIERENDER MANN AN DER FLÖTE Punk-Bands, die Anderson mochte - aber immer nur für 1972 war Rolf Esser aber auch von der Vorgruppe Gentie Giant 10 Minuten