(Paper) -- the Reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev and Their Effect on the USSR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baltic Sea Sweden ◆ Finland ◆ St

of Changing Tides History cruising the Baltic Sea Sweden ◆ Finland ◆ St. Petersburg ◆ Estonia ◆ Poland ◆ Denmark Featuring Guest Speakers Lech Pavel WałĘsa Palazhchenko Former President of Poland Interpreter and Advisor for Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Mikhail Gorbachev July 7 to 16, 2020 Dear Rutgers Alumni and Friends, Join us for the opportunity to explore the lands and legacies forged by centuries of Baltic history. Hear and learn firsthand from historic world leader, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and former president of Poland Lech Wałęsa and from Pavel Palazhchenko, interpreter and advisor for former Soviet Union president Mikhail Gorbachev. This unique Baltic Sea voyage features six countries and seven UNESCO World Heritage sites. Our program is scheduled during the best time of year to experience the natural phenomenon of the luminous “White Nights.” Experience the cultural rebirth of the Baltic States and the imperial past of St. Petersburg, Russia, while cruising aboard the exclusively chartered, five-star Le Dumont-d’Urville, launched in 2019 and featuring only 92 ocean-view suites and staterooms. In the tradition of ancient Viking mariners and medieval merchants, set forth from the cosmopolitan Swedish capital of Stockholm to Denmark’s sophisticated capital city of Copenhagen. Spend two days docked in the heart of regal St. Petersburg, featuring visits to the world-acclaimed State Hermitage Museum, the Peter and Paul Fortress, and the spectacular tsarist palaces in Pushkin and Peterhof. See the storied architecture of Helsinki, Finland; tour the well-preserved medieval Old Town of Tallinn, Estonia; explore the former Hanseatic League town of Visby on Sweden’s Gotland Island; and immerse yourself in the legacy of the Solidarity movement in Gdańsk, Poland. -

Mikhail Gorbachev's Speech in Murmansk at the Ceremonial Meeting on the Occasion of the Presentation of the Order of Lenin and the Gold Star to the City of Murmansk

MIKHAIL GORBACHEV'S SPEECH IN MURMANSK AT THE CEREMONIAL MEETING ON THE OCCASION OF THE PRESENTATION OF THE ORDER OF LENIN AND THE GOLD STAR TO THE CITY OF MURMANSK Murmansk, 1 Oct. 1987 Indeed, the international situation is still complicated. The dangers to which we have no right to turn a blind eye remain. There has been some change, however, or, at least, change is starting. Certainly, judging the situation only from the speeches made by top Western leaders, including their "programme" statements, everything would seem to be as it was before: the same anti-Soviet attacks, the same demands that we show our commitment to peace by renouncing our order and principles, the same confrontational language: "totalitarianism", "communist expansion", and so on. Within a few days, however, these speeches are often forgotten, and, at any rate, the theses contained in them do not figure during businesslike political negotiations and contacts. This is a very interesting point, an interesting phenomenon. It confirms that we are dealing with yesterday's rhetoric, while real- life processes have been set into motion. This means that something is indeed changing. One of the elements of the change is that it is now difficult to convince people that our foreign policy, our initiatives, our nuclear-free world programme are mere "propaganda". A new, democratic philosophy of international relations, of world politics is breaking through. The new mode of thinking with its humane, universal criteria and values is penetrating diverse strata. Its strength lies in the fact that it accords with people's common sense. -

Embargoed Until

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ashley Berke Senior Public Relations Manager 215.409.6693 [email protected] MIKHAIL GORBACHEV TO RECEIVE 2008 LIBERTY MEDAL AT THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER Award to be presented by President George H.W. Bush Philadelphia, PA – The National Constitution Center’s 2008 Liberty Medal will be awarded to former Soviet leader and Nobel Peace Prize winner Mikhail Gorbachev for his courageous role in ending the dangerous, decades-long Cold War and in giving hope and freedom to millions who lived behind the Iron Curtain. The public Liberty Medal ceremony will take place on Thursday, September 18, 2008, at the National Constitution Center on Independence Mall in Historic Philadelphia, and will set the stage for international commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 2009. “This year’s ceremony will be a memorable tribute to a revolutionary thinker with courage and conviction who believed in the power of liberty and openness,” said National Constitution Center President and CEO Joseph M. Torsella. “Mikhail Gorbachev is someone who truly changed the course of history, and we are honored to recognize him.” “During the Cold War, Gorbachev helped replace confrontation with negotiation and established a new climate between East and West,” said Torsella. “He bravely opened the doors of Soviet society to the winds of freedom and change, and he continues to be a voice for an open society today. His vision and strength were central to bringing about a peaceful end to the Cold War, and his remarkable leadership has led to profound and lasting consequences for our nations and for all people who treasure liberty.” This took both vision and courage. -

Timeline of the Cold War

Timeline of the Cold War 1945 Defeat of Germany and Japan February 4-11: Yalta Conference meeting of FDR, Churchill, Stalin - the 'Big Three' Soviet Union has control of Eastern Europe. The Cold War Begins May 8: VE Day - Victory in Europe. Germany surrenders to the Red Army in Berlin July: Potsdam Conference - Germany was officially partitioned into four zones of occupation. August 6: The United States drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima (20 kiloton bomb 'Little Boy' kills 80,000) August 8: Russia declares war on Japan August 9: The United States drops atomic bomb on Nagasaki (22 kiloton 'Fat Man' kills 70,000) August 14 : Japanese surrender End of World War II August 15: Emperor surrender broadcast - VJ Day 1946 February 9: Stalin hostile speech - communism & capitalism were incompatible March 5 : "Sinews of Peace" Iron Curtain Speech by Winston Churchill - "an "iron curtain" has descended on Europe" March 10: Truman demands Russia leave Iran July 1: Operation Crossroads with Test Able was the first public demonstration of America's atomic arsenal July 25: America's Test Baker - underwater explosion 1947 Containment March 12 : Truman Doctrine - Truman declares active role in Greek Civil War June : Marshall Plan is announced setting a precedent for helping countries combat poverty, disease and malnutrition September 2: Rio Pact - U.S. meet 19 Latin American countries and created a security zone around the hemisphere 1948 Containment February 25 : Communist takeover in Czechoslovakia March 2: Truman's Loyalty Program created to catch Cold War -

PERESTROIKA PROPAGANDA in the SOVIET FOREIGN PRESS by Matthew Brown

CONTRIBUTOR BIO MATTHEW BROWN graduated from Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo in June of 2013 with a Bachelor of Arts in History and a minor in Geography & Anthropology. His academic in- terests include the Cold War, the Soviet Union, and revolutionary political theory. Matthew is currently working as a substitute teacher while pursuing a Social Science teaching credential at CSU Long Beach, and is exploring his op- tions for teaching English abroad next school year. He plans on pursuing a Master’s degree in Russian and/or Eastern European history, and would like to eventually teach at the uni- versity level. ECHOES OF A DYING STATE: PERESTROIKA PROPAGANDA IN THE SOVIET FOREIGN PRESS By Matthew Brown “Perestroika means mass initiative. It is the comprehensive devel- opment of democracy, socialist self-government, encouragement of initiative and creative endeavor, improved order and discipline, more glasnost, criticism and self-criticism in all spheres of our society. It is utmost respect for the individual and consideration for personal dignity.”230 The collapse of the Soviet Union marked the end of one of the most tumultuous and volatile periods in modern history. The Soviet Union was not destroyed by a foreign military invasion, nor was it torn apart by civil war. The events that resulted in one of the most powerful countries the world has ever seen literally signing itself out of existence were official government policy, heavily promoted by the Communist Party as the pinnacle of Soviet ideology, and praised by the Soviet intelligentsia as a clear path to a prosperous society. The perestroika and glasnost reforms, instituted under Mikhail Gorbachev, represent the final 230 Mikhail Gorbachev, Perestroika: New Thinking for Our Country and the World (New York: Harper & Row, 1987), 34. -

Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2011 Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War Natalia Zemtsova CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/49 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Mikhail Gorbachev and His Role in the Peaceful Solution of the Cold War Natalia Zemtsova May 2011 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York Advisor: Jean Krasno ABSTRACT The role of a political leader has always been important for understanding both domestic and world politics. The most significant historical events are usually associated in our minds with the images of the people who were directly involved and who were in charge of the most crucial decisions at that particular moment in time. Thus, analyzing the American Civil War, we always mention the great role and the achievements of Abraham Lincoln as the president of the United States. We cannot forget about the actions of such charismatic leaders as Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, Winston Churchill, and Franklin D. Roosevelt when we think about the brutal events and the outcome of the World War II. Or, for example, the Cuban Missile Crisis and its peaceful solution went down in history highlighting roles of John F. -

The Kgb's Image-Building Under

SPREADING THE WORD: THE KGB’S IMAGE-BUILDING UNDER GORBACHEV by Jeff Trimble The Joan Shorenstein Center PRESS ■ POLI TICS Discussion Paper D-24 February 1997 ■ PUBLIC POLICY ■ Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government INTRODUCTION The KGB, under many different sets of graduate student at the Pushkin Russian Lan- initials, evokes frightening memories of the guage Institute in Moscow during the 1979-80 Soviet period of Russian history. A garrison academic year, later as Moscow correspondent state within a state, it provided the terror that for U.S. News & World Report from 1986 to glued the Soviet Union into a unitary force for 1991, Trimble observed the changes not just in evil. Few bucked the system, and dissent was the old KGB but in the old Soviet Union and, in limited, for the most part, to whispers over this paper, based on his own research, he ex- dinner or under the sheets. Millions were herded plains their significance. At a time in American into the communist version of concentration life when we seem to be largely indifferent to the camps, or transported to Siberia, or simply rest of the world, we are indebted to Trimble for executed for crimes no more serious than having his reminder that the past is not too far removed the wrong economic or ideological pedigree. from the present. The KGB, by its brutal behavior, came to be The question lurking between the lines is identified throughout the world with the Soviet whether the changes in image are in fact system of government. When the system, with changes in substance as well. -

Mikhail Gorbachev

Published by Izdatelstvo VES MIR (IVM) for the Gorbachev Foundation © The Gorbachev Foundation, 2006 The Gorbachev Foundation: 39 Leningradsky Prospect, bdg. 14 Moscow125167, Russian Federation Phone/Fax: +7 495 945 74 01 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.gorby.ru Izdatelstvo VES MIR: 9a Kolpachnyi pereulok, Moscow, 101831 Russian Federation Phone: +7 495 623 85 68 Fax: +7 495 625 42 69 E-mail: [email protected] http//www.vesmirbooks.ru ISBN: 5-7777-0343-7 Printed in the Russian Federation Contents Contents SPEECHES 7 The Nobel Lecture 9 From the Address to the 43rd Session of the United Nations General Assembly 26 Final Televized Address as President of the USSR 46 Twenty Years Since the Start of Perestroika 50 ARTICLES 59 9/11: Letter to the New York Times 61 A Coalition for a Better World Order (The New York Times) 62 Transforming Trust Into Trade (The New York Times) 64 Take a Page from Kennedy (TIME) 66 A President Who Listened (The New York Times) 69 What Made Me a Crusader 71 Nature Will Not Wait 74 Why the Poor Are Still With Us (Global Agenda) 77 Mikhail Gorbachev INTERVIEWS 81 Transcript of Gorbachev’s Interview with Brian Lamb (PBS Booknotes) 83 The American and Russian People Don’t Want a New Confrontation (Newsweek) 104 Democracy Will Fit the Needs of Every Nation (Christian Science Monitor) 110 We All Lost Cold War (Washington Post) 115 No Turning Back for Russia (Los Angeles Times) 119 The Greening of Mikhail Gorbachev (International Herald Tribune) 122 Perestroika 20 Years Later: Gorbachev Reflects (Global Viewpoint) 125 Gorbachev’s Message Is Still Worth Listening To (The Times) 133 ABOUT GORBACHEV 135 Man of the Decade: The Unlikely Patron of Change By Lance Morrow (TIME) 137 Mikhail Gorbachev By Tatiana Tolstaya 142 Raisa, We Loved You By Anatole Kaletsky (The Times) 147 Speeches The Nobel Lecture Mr. -

The End of the Cold War

The end of the Cold War The Cold War had seen more than four decades of tension between the two superpowers, the USA and the USSR. There had been a number of crises, and a whole generation had grown up with the fear of nuclear war. However, by the early 1990s the Cold War had officially ended. The last part of this course will examine a number of reasons why the Cold War finally came to an end. Factor 1 – Détente Détente means an easing of the tension between two countries. In the later 1960s and 1970s, the relationship between the USA and the USSR improved. This arguably helped bring about peace between the superpowers in the long term. Why détente? There were a number of reasons why both countries were keen to improve relations in the 1960s and 1970s. The Cuban Missile Crisis had brought the superpowers close to nuclear war. They wanted to avoid similar confrontations in future as they realised a full-scale nuclear war would lead to the destruction of both countries. Both countries were spending huge sums on the arms race – money which could be better spent on improving the lives of ordinary citizens in America and the Soviet Union. In America and many other Western countries, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) attracted widespread support. CND wanted all countries to get rid of their nuclear weapons and put pressure on the US Government to disarm. Following its disastrous involvement in the Vietnam War, many Americans wanted to avoid foreign wars. This encouraged the US Government to seek better relations with the two most powerful communist nations – China and the USSR. -

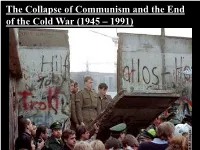

The Collapse of Communism and the End of the Cold War (1945 – 1991) Content Statement

The Collapse of Communism and the End of the Cold War (1945 – 1991) Content Statement • The collapse of the Communist governments in Eastern Europe and the USSR brought an end to the Cold War Objectives • Define or describe the following terms: –Détente –Reagan Doctrine –“Star Wars” Program –Mikhail Gorbachev –Commonwealth of Independent States Objectives • Explain how the collapse of Communist governments in Eastern Europe and the USSR brought an end to the Cold War era • What role did the United States play in the collapse of Communism? The Cold War • The period from 1945 to 1991 saw a host of important events in the Cold War battle between the U.S. and the Soviet Union • There were multiple causes for the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union • The effect of this collapse was the reduction of tensions between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. that had characterized the Cold War period for 45 years Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 • President Nixon believed in pursuing a policy of détente - a relaxing of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union • Nixon sought to halt the build-up of nuclear weapons • In 1972, he became the first President to visit Moscow, where he signed an agreement (SALT) with Soviet leaders Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 –The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union on the issue of armament control –The two rounds of talks and agreements were SALT I and SALT II Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 • The agreement limited the development of defensive missile systems • Nixon further agreed to sell American grain to the Soviets to help them cope with food shortages • In 1973, when war broke out in the Middle East, the United States and Soviet Union further cooperated in pressuring Israel and the Arab states to conclude a cease-fire Détente with the Soviet Union, 1972 • Détente also allowed the United States to reduce its armed forces from 3.5 million to 2.3 million, and to withdraw U.S. -

By George Gerbner Tbe August Coup

1 MEDIA AND MYSTERY IN. THE RUSSIAN COUP; By George Gerbner Tbe August Coup: Tbe Trutb and tbe Lessons~ By Mikhail Gorbachev. HarperCollins. 127 pp. $18.00 Tbe Future Belongs to Freedom~ By EduardShevardnadze. New York: The Free ,Press, 1991. 237 pp. Eyewitness; A Personal Account of the Unraveling of tbe Soviet Union. By Vladimir Pozner. Random House. 220 pp. $20.00 . Seven Days Tbat Sbooktbe World;Tbe Collapse of soviet communism. by stuart H. Loory and Ann Imse. Introduction by Hedrick Smith. CNN Report, Turner Publishing, Inc. 255 pp. Boris Yeltsin: From Bolsbevik to Democrat. By John Morrison. Dutton. 303pp. $20. Boris Yeltsin, A Political Biograpby. By Vladimir Solvyov and Elena Klepikova. Putnam. 320 pp. $24.95 We remember the Russian coup of A~gust 1991 as a quixotic attempt, doomed to failure, engineered by fools and thwarted by a spontaneous uprising. As Vladimir Pozner's Eyewitness puts it, our imag~ of the coup leaders is that of "faceless party hacks ••• Hollywood-cast to fit the somehow gross, repulsive, and yet somewhat comical image" of the typical Communist bureaucrat.(p. 10) Well, that image is false. More than that, it obscures the big story of the coup .and its consequences for Russia and the world. By falling back on a cold-war caricature ' and . accepting what Shevardnadze calls "the export version" of perestroika, the U.s. press, and Western media generally, may have missed the story of the decade. .' The men who struck on August 19, : 1991 were, as Pozner himself · argues,,"far from inept ,and, indeed, ' ready to do whatever was necessary to win. -

Perestroika and the Collapse of the Soviet Union Laura Cummings the Late 1980S Were a Period of Change, Reform and Eventually Demise Within the Soviet Union

History Gorbachev’s Perestroika and the Collapse of the Soviet Union Laura Cummings The late 1980s were a period of change, reform and eventually demise within the Soviet Union. These political and economic reforms were spearheaded by Mikhail Gorbachev, who became General Secretary in 1985 and used his position to enact a series of humanitarian, democratic reforms aimed at improving the communist system from within. Under previous leaders, the Soviet economy stalled, party ide- ology drifted away from its Marxist roots and the government continued to wield an oppressive hand over the people. In an attempt to !x the "agging economy and re-energize party doctrine, Gorbachev introduced the philosophy of perestroika, meaning restructuring. Perestroika allowed for more freedoms in the market, in- cluding some market economy mechanisms. However, perestroika did not only deal with the economy; it dealt with politics as well. The political reorganization called for a multi-candidate system and allowed opposition groups to speak out against communism. Although the motivations and intentions of perestroika are debated in the historiography of the period, its importance to the Cold War is clear- ly evident. To some degree, perestroika contributed to the fall of communism and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Although Gorbachev was trying to save the system, his reforms contributed to its end. The fall of the Soviet Union, although it was not entirely surprising, rocked the world in 1991. A number of factors both behind the iron curtain and abroad contributed, in some way, to the collapse of the communist regime, including American rearmament, growing rebellious sentiments within the Soviet bloc and Gorbachev’s reform policies, speci!cally perestroika.