Robin Hood's Pennyworth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Document

Statement of Consultation Part 1 Regulation 18 Consultation on the Draft Site Allocations and Development Management Plan Braintree District Council January 2014 Contents 1. Background 2. Introduction 3. Consultation Process 4. Consultation Responses Received 5. Summary of Main Issues and Officer Response Appendix Appendix 1 a) Copy of the response form b) Copy of the guidance notes Appendix 2 a) Copy of the notification letter sent to statutory consultees b) Copy of the notification letter send to non-statutory consultees c) Appendix 3 List consultees Appendix 4 a) Copy of the advert placed in local newspapers b) Copy of the posters used to advertise consultation c) Example of a site notice Addendum Copy of agendas, reports and minutes of the LDF Sub Committees of the 26 th March, 11 th April, 8 th May, 30 th May, 13 th June, 17 th June, 11 th July, 24 th July 2013. 2 1. Background In accordance with Regulation 22(l) (c) (i-iv) of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning)(England) Regulations 2012, this is a factual statement which sets out the following information; (i) Which bodies and persons Braintree District Council invited to make representations under Regulation 18 on the draft Site Allocations and Development Management Plan (ii) How these bodies and persons were invited to make representations under Regulation 18 (iii) A summary of the main issues raised by the representations made pursuant to Regulation 18 (iv) How representations made pursuant of Regulation 18 were taken into account. 2. Introduction Braintree District Council adopted its Core Strategy in September 2011. -

Earls Colne. Coe Zachary, Coachmaker& Wheelwght :Monk Joseph, Assist

(ESSEX.] THE COLNES. 60 POST OFFICE PUBLIC OPF'ICJ!.RS :- Parish Clerk, Charles Wells Coroner, Willi!lm Codd, e8q. Maldon · Registrars of Marriages, Mr. Richard Poole, Maldon; Registrar (If Btrths, Marriage• ~ Death1, Mr. Francis & Mr. William Boston, Southminster Lufkin, Purleigh National School, Miss Hannah Gosling, mistress Relieving Officer, Mr. CharleS! Croxon, Purleigh 1 TB!: COJ.NES. bells,and is situated on rising ground. The li-ring is a rec. EARLS CoLNE derives its name from the river Colne, and tory, value £800, with a parsonage and 56 acres of glebe, its ancient occupation by the De Veres, Great Chamber in the presentation of the Governors of Christ Hospital; the lains of England, Earls of Oxford, and Dukes of Dllb!in, Rev. John Greenwood, n.n., is the present incumbent. A who had a seat here, called Hall Place, with a park of neat National school was erected in 1847, at a cost of £360, about 700 acres detached, and which stood on one side of by subscription, aided by the National Society's Diocesan the church. Earls Colne, a town as ancient as the time Board, and by the Committee of CoulJcil on Education. of King Edward the Confessor, situate near the banks of Robert Hills, Esq., and John Jeremiah Mayhew, Esq., are the Colne, is in Hinckford Hundred and in Halstead lords of the manor, and have seats in the parish. Union, North Essex, on the road from Halstead to BUNTING'S GREEN, BOOSE'S GREEN and TOLMANS' Colchester, f) miles north-west of Marks Tey station, 48 GREEN lie to the west. -

Colne Engaine Parish Magazine

Colne Engaine Parish Magazine For all the people who live here October 2014 COLNE ENGAINE PARISH MAGAZINE OCTOBER 2014 EDITORIAL THE PARISHES Editor: Michael Estcourt Earls Colne, White Colne and Colne 2 Brickhouse Road, CO6 2HL Engaine parishes are under the care of Tel/Fax: 01787 220049 our Team Vicar and arrangements for [email protected] Baptisms / Weddings / Funerals and All copy should be sent to Michael. other services or use of the Church Advertising: Terry Hawthorn should be made with; 6 High Croft, CO6 2HE. T: 01787 223140 Team Vicar: The Reverend Peter Allen [email protected] St Andrew’s Rectory, 5 Shut Lane, All advertising should be sent to Terry. Earls Colne Design: Juliet Townsend T: 01787 220347 14 Oddcroft, CO6 2ET. T: 01787 222459. [email protected] [email protected] Church Warden: Mr Desmond Shine 4 Brickhouse Road CO6 2HL PARISH COUNCIL T: 01787 223378 [email protected] Parish Clerk: Terry Rootsey Buntings Green Cottage, Halstead Road, PCC Secretary: Mrs Laura La Roche Colne Engaine CO6 2JG. Croft Cottage, The Green, Colne Engaine T: 01787 220200 T: 01787 223391 [email protected] ADVERTISING Our monthly magazine (double issues 1/4 Page 62 x 88mm £10 / £50 pa in July/August and December/January) 1/2 Page 128 x 88mm £17 / £75 pa is delivered free of charge to all 400 Full Page 128 x 180mm £20 or £100 pa households in Colne Engaine Cheques payable to Colne Engaine PCC. and Countess Cross. TO OUR READERS Please remember to mention this magazine if you answer any of the advertisements. -

ESSEX. [KELLY's Farmlilr8-"-Continued

466 FAR ESSEX. [KELLY'S FARMlilR8-"-continued. Parker Samuel, LowerFord end. Claver- PerryJ.Yntnessing. ball,Essing,fJrentwd Orpen Robert Lawrence, Rampart farm, ing, Bishop's Stortford ..r Perry J .. Limbourne pk.MWldon,Maldon Lexden, Colchest&r Parker Thomas, Cranham, Romford Perry Mrs. Thomas, Little HalliDgbury, OrpenW.W.Walthm.hall,Takely.Chlmsfd Parker T. MUD80DS fm.Ardleigh,Colchstr Bishop's Stortford Osborn 8.Schoolla.. Langham, Colchestr t ParkerW.Blewgates,Hgh.Ongr.lngtstne PerryW.Clmnt.'1! hall,Hawkwell,Chlmsfd Osborn William, Earls Colne, Halstead ParkinSamuel, Lanceley9, Helion Bump- Pertwee Albert, The l"en farms, Wood- ~sbome Mrs. C8l'oline, Coggeshall road, stead, Hav'erhill ,ham Ferrers, Chelmsford Dedham S.O Parlby John, Mountnessing, Brentwood Pertwee J. Old hall, Boreham, Chelmsfd Osborne G. Burkitt's farm, Dedham S.O PannentetWm. Russell's farm,Wethen- Pertwee T. B. Langenhoe lodge, Colehstr Osborne George, St. Leonard's farm, field. Braintree Peters James, South Benfleet, Chelmsfd Fryerning, Ingatestone Parnell Mrs. The Tye, Margaretting, Pettican George, Fingringhoe, Colehestr Osborne Mrs. Jane, Ardleigh,Colehester Ingatestone Pettican G. Gate frm.Abberton,Colehstr Osborne John, Peldon, Colchester Parris Edward, Mascall's Bury, White Pettitt Arthur, Mount Bures, Colchester Overall William, Crosslees & Leaper's Roothing, Chelmsford Pettitt B. Warishhall,Takeley,Chelmsfd farms, Moreton, Brentwooo Parrish Coulson D. Dagenham, Romford Pettitt Charles (exors. of), Baker's hall, Overall William, Felsted S.O . Parrish -

THURSDAY 31ST DECEMBER 2020 Number: 566 Email: [email protected]

BRAINTREE AND DISTRICT NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH Affiliated to Essex County Neighbourhood Watch Association a registered Charity No: 1168988 THE WEEKLY NEIGHBOURHOOD WATCH NEWSLETTER TWO PAGE ISSUE THURSDAY 31ST DECEMBER 2020 Number: 566 Email: [email protected] THEFTS FROM PERSONS BRAINTREE THEFTS OF MOTOR VEHICLES Lakes Industrial Park, Lower Chapel Hill WITHAM Dec. 22nd between 12:30hrs and 14:13hrs. Mersey Road th Suspect unknown removed victim’s bank card from Dec 15 between 20:10hrs and 21:41hrs. a wallet and spent £102.98 at various and shops via Suspect unknown removed a white Transit. the contactless card Yew Close th Coggeshall Road December 15 between 18:30hrs and 23:01hrs. December 16th between 12:30hrs and 18:55hrs. Suspect unknown removed a white Audi 55. Suspect unknown removed victim’s mobile phone HALSTEAD Stanstead Road th th from her shoulder bag whilst victim was shopping Between Dec 14 21:40hrs and Dec 15 06:55hrs. in a store. The phone was later found discarded Suspect unknown stole a Ford Kuga. near a roundabout in Claypitts. DWELLING HOUSE BURGLARIES WITHAM SIBLE HEDINGHAM Rockways Close Grove Centre Between Dec 12th 22:30hrs and Dec 13th 09:49hrs. Dec 15th between 13:30hrs and 14:33hrs Suspect unknown gained entry to property and Suspect unidentified removed victim’s bank card stole £30 from victim’s wallet which was inside his from victim’s daughter’s pocket. The suspect then trouser’s pocket. used the card for transactions in Botts and tried in HALSTEAD Kingfisher Meadows Superdrug but it was declined Dec 15th between 05:45hrs and 06:19hrs. -

Essex Journal

Essex SPRING 2006 Journal A REVIEW OF LOCAL HISTORY & ARCHAEOLOGY R. MILLER CHRISTY A TOAD-EATER AND USURER THE PURITAN HARLACKENDEN FAMILY PLESHEY COLLEGE THE APPRENTICES AND THE CLERGYMEN SPRING 2006 Vol. 44 No.1 ESSEX ISSN 0014-0961 JOURNAL (incorporating Essex Review) EDITORIAL 2 OBITUARIES 3 R. MILLER CHRISTY: Essex Naturalist and Antiquary – Part II 5 W. Raymond Powell AN INVENTORY AT PLESHEY COLLEGE 12 Christopher Page A TOAD-EATER AND USURER FROM LAMBOURNE: Thomas Walker (1664-1748) of Bishops Hall 15 Richard Morris THE PURITAN HERITAGE OF THE HARLACKENDEN FAMILY OF EARLS COLNE 19 Daphne Pearson THE APPRENTICES AND THE CLERGYMAN: An episode in the history of steam ploughing 22 Chris Thompson BOOK REVIEWS 24 FORTHCOMING EVENTS and PLACES to VISIT 28 Hon. Editor: Michael Beale, M.A., The Laurels, The Street, Great Waltham, Chelmsford, Essex CM3 1DE (Tel: 01245 360344/email: [email protected]) The ‘ESSEX JOURNAL’ is now published by and is under the management of an Editorial Board consisting of representatives of the Essex Archaeological and Historical Congress, the Friends of Historic Essex, the Essex Record Office (on behalf of the Essex County Council) and the ˙Hon. Editor. It was recognised that the statutory duties of the County Council preclude the Record Office from sharing in the financial commitments of the consortium. The Chairman is Mr. Adrian Corder-Birch M.I.C.M., F.Inst.L.Ex., one of the Congress representatives, the Hon. Secretary is Mrs. Marie Wolfe and the Hon.Treasurer, Mrs. Geraldine Willden. The annual subscription of £10.00 should be sent to the Hon. -

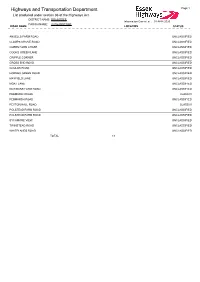

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List Produced Under Section 36 of the Highways Act

Highways and Transportation Department Page 1 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: BRAINTREE Information Correct at : 01-APR-2020 PARISH NAME: ALPHAMSTONE ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS ANSELLS FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED CLAMPS GROVE ROAD UNCLASSIFIED COBBS FARM CHASE UNCLASSIFIED COOKS GREEN LANE UNCLASSIFIED CRIPPLE CORNER UNCLASSIFIED CROSS END ROAD UNCLASSIFIED GOULDS ROAD UNCLASSIFIED HORNES GREEN ROAD UNCLASSIFIED MAYFIELD LANE UNCLASSIFIED MOAT LANE UNCLASSIFIED NEWMANS FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED PEBMARSH ROAD CLASS III PEBMARSH ROAD UNCLASSIFIED PEYTON HALL ROAD CLASS III POLSTEAD FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED POLSTEAD FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED SYCAMORE VIEW UNCLASSIFIED TWINSTEAD ROAD UNCLASSIFIED WHITELANDS ROAD UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 19 Highways and Transportation Department Page 2 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: BRAINTREE Information Correct at : 01-APR-2020 PARISH NAME: ASHEN ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS AIRFIELD ROAD UNCLASSIFIED ASHEN CLOSE PRIVATE ROAD ASHEN HILL STOKE HILL UNCLASSIFIED ASHEN LANE UNCLASSIFIED ASHEN ROAD CLASS III ASHEN ROAD UNCLASSIFIED BRADLEY HILL CLASS III DOCTOR'S LANE UNCLASSIFIED FOXES ROAD CLASS III HOLLOW ROAD CLASS III ORCHARD FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED STOURS LANE UNCLASSIFIED THE STREET CLASS III UPPER FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 14 Highways and Transportation Department Page 3 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. DISTRICT NAME: BRAINTREE Information Correct at : 01-APR-2020 PARISH NAME: BARDFIELD SALING ROAD NAME LOCATION STATUS BOARDED BARNS ROAD UNCLASSIFIED CROWS GREEN ROAD UNCLASSIFIED ELMS FARM ROAD UNCLASSIFIED LONG GREEN LANE UNCLASSIFIED PLUMS LANE UNCLASSIFIED SALING ROAD CLASS III STEBBING ROAD UNCLASSIFIED WOOLPITS ROAD UNCLASSIFIED TOTAL 8 Highways and Transportation Department Page 4 List produced under section 36 of the Highways Act. -

Earls Colne Heritage Museum

3. Welcome 4-5. St. Andrew’s - Letter from Peter Editor: Sue Kenneally 5. Prayers For The Parishes The Old Cottage, Brickhouse Road, CO6 2HJ 6. Whist Drive; W.I. T: 01787 220402 7. Church Services for December E: [email protected] 8. Church Services for January All copy should be sent to Sue. 9. Church Notices 10-11. Gardening Design: Jonathan White 11. 3.30 Express E: [email protected] 12. The Village Hall Advertising: Terry Hawthorn 15. Carols On The Green 16-17. Our Primary School 6 High Croft, CO6 2HE. T: 01787 223140 19. Festival of Christmas Trees E: [email protected] 21. F.A.C.E.S Christmas Fair All advertising should be sent to Terry. 23. Save our Scout Hut 24-25. Parish Council Notices 26. Walking Groups 29. Your Church Needs You Our monthly magazine (double issues 30-31. Goodbye Reverend Pete in July/Aug and Dec/Jan) is delivered free 33. C.E.D.S; Open House; School Hall of charge to all 400 households in Colne 36-37. Village History Engaine and Countess Cross. 39. Correspondence 42. Foodbank Winter Appeal 1/4 Page 62 x 88mm £10 / £55 pa 46-47. Remembrance Day 1/2 Page 128 x 88mm £17 / £80 pa 49. Youth Club Full Page 128 x 188mm £20 or £110 pa 51. Snr Citizens Lunch Cheques payable to Colne Engaine PCC. The Secrets of the Valley 53. Correspondence Readers, please remember to mention From The Four Colnes Magazine this magazine if you answer any of the 55. Festival Committee advertisements. -

Parish Magazine of Earls Colne & White Colne

The Parish Magazine of Earls Colne & White Colne � � � � � September 2021 Dear Readers, What a year it has been! I’m not talking about the year filled with pandemic-related restrictions and lockdowns, which though lifted, still presents us with many challenges. No, I’m talking about the year within which my entire life and my involvement within our parishes and communities have changed. On September 13th a year ago I was ordained Deacon in the Holy Church of God. Nine months later on the 26th June, I was ordained Priest, the second of the three Holy Orders. For information, the third Holy Order is that of Bishop . and I currently have no plans to get to those dizzy heights! Two ordinations in less than 12 months and I couldn’t be happier. But most of all, I am extremely grateful to everyone who has journeyed with me, prayed with and for me, and supported me especially when the dark days rolled in, and times seemed hard and unbearable. And that’s just in relation to all the essays I had to write!! There can’t be anywhere better than the communities of the lovely villages/parishes in which I serve, alongside Revd Mark, Revd Hugh and the lay ministry teams of the Three Colnes Churches. And for that I am truly thankful to the God who sustains us and enables us to share our ministry with you, our wonderful neighbours and friends. My thanks also goes to all of you who have been so generous, taking time to say hello, congratulations, well done and to just be a friendly face as I find my feet. -

Colne Engaine Parish Magazine

Editor: Sue Kenneally 3. Welcome The Old Cottage, Brickhouse Road, CO6 2HJ 5-6. St. Andrew’s - Rev’d. Mark Payne T: 01787 220402 7. Church Notices; Contacts E: [email protected] 9. Community Response All copy should be sent to Sue. 10-11. Our Primary School Design: Jonathan White 13-14. Parish Council E: [email protected] 15. Consider Donating 17. Harvest Lunch Advertising: Terry Hawthorn 19. Pilgrims and Strangers 6 High Croft, CO6 2HE. T: 01787 223140 22-24. Gardening E: [email protected] 27. Churches Open Again All advertising should be sent to Terry. 29. Quiz Night Fundraiser 30-31. Village Hall 33. Every Picture Tells A Story... Our monthly magazine (double issues 35. Earls Colne Heritage Museum in July/Aug and Dec/Jan) is delivered free 37. Correspondence of charge to all 400 households in Colne 39. Sunflowers and Snakes Engaine and Countess Cross. 41. Youth Club; Senior Citizens Lunch 1/4 Page 62 x 88mm £10 / £55 pa 42. Whist Drives 1/2 Page 128 x 88mm £17 / £80 pa 43. Recipe Corner Full Page 128 x 188mm £20 or £110 pa 45. Puzzles Cheques payable to Colne Engaine PCC. 47. Earls Colne Library Readers, please remember to mention 51. Braintree Area Foodbank this magazine if you answer any of the 53. The Four Colne Magazine 1920 advertisements. 54. Useful Numbers; We welcome advertising in our magazine, Advertisers Index the income from which helps to cover 55. On the Buses production costs. This does not imply any 56. Defibrillator Operators endorsement or approval of the products 57. -

Earls Colne's Early Modern Landscapes

EARLS COLNE’S EARLY MODERN LANDSCAPES For my father Coinneach MhicFhionghuin (1927–1990), from the Isle of Skye, Scotland & Mary Valley, Queensland, Australia & my Great Aunt Mary Wall (1904–1992) from Cumberland, England, and Red Deer, Alberta, Canada. Earls Colne’s Early Modern Landscapes D OLLY MACKINNON University of Queensland, Australia First published 2014 by Ashgate Publishing Published 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Copyright © Dolly MacKinnon 2014 Dolly MacKinnon has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: MacKinnon, Dolly. Earls Colne’s early modern landscapes / by Dolly MacKinnon. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–7546–3964–0 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Earls Colne (England) – History. 2. Earls Colne (England) – Historical geography. 3. Material culture – England – Earls Colne – History. -

Chapter Five the Earls and Royal Government

Chapter Five The Earls and Royal Government: General There are two angles from which the subject of the earls and royal government should be approached. The earls were in- volved at every level of government, from the highest offices of household and administration to the hanging of a thief on their own lands. They were also subject to the actions of government in its many forms. While it is useful to consider the activity of the earls in government separate from the impact of government upon them, there is no clear division between these two aspects. An earl that lost a legal dispute in the king's court was, as a major vassal of the king, a potential member of that same court. An earl that paid the danegeld due from his fief and vassals was both tax-collector and tax-payer. The obvious place to start an examination of the earls' role in government is the royal household, the central govern- ment institution of western kings since before Charlemagne. In Henry II's reign, several of the chief offices of the house- hold were held by earls. Two earls were recognised by Henry II as stewards in the years on either side of his succession to the throne. At some time between June 1153 and December 1154, Henry II recognised Robert earl of Leicester (d. 1168) as steward of England and Normandy (1). The earl had not been a steward under .(1) Re esta, iii, no.439. Shortly before this, the same grant had been made by Henry to Earl Robert's son, probably to avoid a too early contradiction in Earl Robert's allegiance to King Stephen: Ibid., no.438.