Int Cedaw Ngo Mex 31412 E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xhdy-Tdt San Cristobal De Las Casas

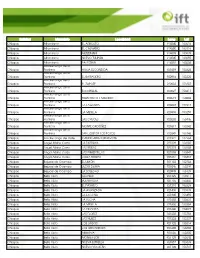

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Chiapas Acala 2 POTRANCAS 925549 163422 Chiapas Acala 20 DE NOVIEMBRE 925349 163218 Chiapas Acala 6 DE MAYO 925311 163024 Chiapas Acala ACALA 924820 163322 Chiapas Acala ADOLFO LÓPEZ MATEOS 925337 163639 Chiapas Acala AGUA DULCE (BUENOS AIRES) 925100 163001 Chiapas Acala ARTURO MORENO 925345 163349 Chiapas Acala BELÉN 924719 163340 Chiapas Acala BELÉN DOS 925318 162604 Chiapas Acala CAMINO PINTADO 925335 163637 Chiapas Acala CAMPO REAL 925534 163417 Chiapas Acala CARLOS SALINAS DE GORTARI 924957 162538 Chiapas Acala CENTRAL CAMPESINA CARDENISTA 925052 162506 Chiapas Acala CRUZ CHIQUITA 925644 163507 Chiapas Acala CUPIJAMO 924723 163256 Chiapas Acala DOLORES ALFARO 925404 163356 Chiapas Acala DOLORES BUENAVISTA 925512 163408 Chiapas Acala EL AMATAL 924610 162720 Chiapas Acala EL AZUFRE 924555 162629 Chiapas Acala EL BAJÍO 924517 162542 Chiapas Acala EL CALERO 924549 163039 Chiapas Acala EL CANUTILLO 925138 162930 Chiapas Acala EL CENTENARIO 924721 163327 Chiapas Acala EL CERRITO 925100 162910 Chiapas Acala EL CHILAR 924742 163515 Chiapas Acala EL CRUCERO 925152 163002 Chiapas Acala EL FAVORITO 924945 163145 Chiapas Acala EL GIRASOL 925130 162953 Chiapas Acala EL HERRADERO 925446 163354 Chiapas Acala EL PAQUESCH 924933 163324 Chiapas Acala EL PARAÍSO 924740 162810 Chiapas Acala EL PARAÍSO 925610 163441 Chiapas Acala EL PORVENIR 924507 162529 Chiapas Acala EL PORVENIR 925115 162453 Chiapas Acala EL PORVENIR UNO 925307 162530 Chiapas Acala EL RECREO 925119 163429 Chiapas Acala EL RECUERDO 925342 163018 -

Diagnóstico Municipal Con Perspectiva De Género

DIAGNÓSTICO MUNICIPAL CON PERSPECTIVA DE GÉNERO LA GRANDEZA - CHIAPAS Elaboración Elías Rodríguez Lucas Alejandro Fúnez Khouri Este producto es generado con recursos del Programa de Fortalecimiento a las Políticas Municipales de Igualdad y Equidad entre Mujeres y Hombres, FODEIMM El “INMUJERES” no necesariamente comparte los puntos de vista expresados por las (los) autoras (es) del presente trabajo Este programa es público y queda prohibido su uso con fines partidistas o de promoción personal OCTUBRE DE 2012 CHIAPAS, MÉXICO CONTENIDO Introducción .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Diagnóstico con perspectiva de género ......................................................................................................... 6 Población.................................................................................................................................................. 6 Educación................................................................................................................................................. 9 La educación y los Objetivos de Desarrollo del Milenio ................................................................... 14 Salud ...................................................................................................................................................... 15 Empleo .................................................................................................................................................. -

Matrimonio Forzado Y Embarazo Adolescente En Indígenas En Amatenango Del Valle, Chiapas

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22185/24487147.2020.106.30 Matrimonio forzado y embarazo adolescente en indígenas en Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas. Una mirada desde las relaciones de género y el cambio reproductivo Forced marriage and adolescent pregnancy in indigenous people in Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas. An approximation from gender relationes and reproductive change Juana Luna-Pérez, Austreberta Nazar-Beutelspacher, Ramón Mariaca-Méndez y Dulce Karol Ramírez-López Consultora Independiente, Departamento de Salud de El Colegio de la Frontera Sur en Chiapas, México, Director General de Estadística e Información Ambien- tal de la SEMARNAT, México, Ciencias Políticas y Administración Pública de la Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, México Resumen En este estudio, se analizan los cambios en la frecuencia del matrimonio forzado y del embara- zo adolescente en una comunidad indígena tseltal de Chiapas. Fueron utilizadas metodologías cuantitativas y cualitativas, así como una revisión de fuentes secundarias de información. Los resultados muestran que el matrimonio forzado ha disminuido y, entre las más jóvenes se han incrementado las uniones “voluntarias” que acompañan la disminución de la edad de unión. Lo anterior, pese al incremento de la escolaridad de las mujeres, el acceso al trabajo remunerado y a los métodos anticonceptivos. Se discute el papel de las relaciones de género en el matrimonio forzado y el embarazo adolescente, así como el posible impacto que tendría la modificación de la legislación para prohibir el matrimonio infantil en México. Palabras clave: Matrimonio infantil, Chiapas, trabajo remunerado, escolaridad, anticoncepción. Abstract In this study, the changes in the frequency of forced marriage and adolescent pregnancy in an indigenous Tseltal community of Chiapas are analyzed. -

INTRODUCCIÓN Sin Duda, Uno De Los Aspectos Relevantes Dentro Del

INTRODUCCIÓN Sin duda, uno de los aspectos relevantes dentro del modelo de formación del estudiantado en la Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas (UNICH), es que los estudiantes aprendan a desarrollar sus habilidades prácticas a partir de vincularse con los quehaceres y la problemática de la sociedad, aplicando sus conocimientos e interviniendo en las acciones de acompañamiento para el mejoramiento de las condiciones de trabajo y bienestar de las comunidades. La presente memoria es el resultado de la experiencia de vinculación comunitaria realizada entre un grupo de productores, estudiantes y maestros de tiempo completo de la licenciatura en Desarrollo Sustentable de la Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas, en Oniltic, municipio de San Juan Cancuc. La vinculación con la comunidad es un eje central en el proceso de aprendizaje del estudiante de la UNICH, mismo que sirve para que vaya conociendo las intervenciones existentes entre el qué hacer, las formas de vida, el desarrollo económico, social, político y cultural de las comunidades y grupos sociales, con la aplicación de conocimientos en el aprovechamiento de sus recursos y la conservación de su entorno sociocultural y ambiental. En relación a lo anterior, en marzo de 2007 se realizó una de las primeras visitas a la comunidad de Oniltic del municipio de San Juan Cancuc, lugar donde se realizaron actividades de vinculación de la universidad, aclarándole a la gente de la comunidad que el propósito era obtener (al final del proceso) un diagnóstico que reflejara las características socioeconómicas, productivas y ambientales de la comunidad. (En esta primera visita logramos hablar con las autoridades municipales y los que más tarde fueron participantes del proyecto, con ellos hablamos de la posibilidad de impulsar la organización de los productores). -

Comision Nacional Para El Desarrollo

Viernes 7 de noviembre de 2008 DIARIO OFICIAL (Primera Sección) COMISION NACIONAL PARA EL DESARROLLO DE LOS PUEBLOS INDIGENAS CONVENIO de Coordinación para la ejecución del Programa Organización Productiva para Mujeres Indígenas, que celebran la Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas y los municipios de Chilón, Chanal, Tenejapa, Larráinzar, Oxchuc, Zinacantán, Huixtán, Ocotepec, San Andrés Duraznal, Sabanilla, Marqués de Comillas, Salto de Agua, Maravilla Tenejapa, Huitiupán, San Juan Cancuc, Sitalá, Santiago el Pinar, Jitotol, Pantepec, Tumbalá, Las Margaritas, Chamula, Teopisca y El Bosque del Estado de Chiapas. CONVENIO DE COORDINACION PARA LA EJECUCION DEL PROGRAMA ORGANIZACION PRODUCTIVA PARA MUJERES INDIGENAS, EN ADELANTE “EL PROGRAMA” DURANTE EL EJERCICIO FISCAL 2008; QUE CELEBRAN LA COMISION NACIONAL PARA EL DESARROLLO DE LOS PUEBLOS INDIGENAS, REPRESENTADA POR EL C. JESUS CARIDAD AGUILAR MUÑOZ, EN SU CARACTER DE DELEGADO EN EL ESTADO DE CHIAPAS, A QUIEN EN LO SUCESIVO SE LE DENOMINARA “LA COMISION”; Y LOS MUNICIPIOS DE CHILON, CHANAL, TENEJAPA, LARRAINZAR, OXCHUC, ZINACANTAN, HUIXTAN, OCOTEPEC, SAN ANDRES DURAZNAL, SABANILLA, MARQUES DE COMILLAS, SALTO DE AGUA, MARAVILLA TENEJAPA, HUITIUPAN, SAN JUAN CANCUC, SITALA, SANTIAGO EL PINAR, JITOTOL, PANTEPEC, TUMBALA, LAS MARGARITAS, CHAMULA, TEOPISCA Y EL BOSQUE TODOS DEL ESTADO DE CHIAPAS, REPRESENTADO EN ESTE ACTO POR LOS PRESIDENTES MUNICIPALES: ANTONIO MORENO LOPEZ, JOSE LUIS ENTZIN SANCHEZ, PEDRO MEZA RAMIREZ, ALFONSO DIAZ PEREZ, JAIME SANTIZ GOMEZ, ANTONIO -

Desarrollo Sustentable, Se Ejercieron 198.6 Millones De Pesos

PRESUPUESTO DEVENGADO ENERO - DICIEMBRE 2010 198.6 Millones de Pesos Administración del Agua 35.4 17.8% Protección y Ecosistema Conservación 24.3 del Medio 12.3% Ambiente y los Rececursos Naturales Medio Ambiente 124.0 14.9 62.4% 7.5% Fuente: Organismos Públicos del Gobierno del Estado En el Desarrollo Sustentable, se ejercieron 198.6 millones de pesos. Con el fin de fomentar el desarrollo de la cultura ambiental en comunidades indígenas, se realizaron 4 talleres de capacitación en los principios básicos del cultivo biointensivo de hortalizas. Para el fortalecimiento y conservación de las áreas naturales protegidas de carácter estatal, se elaboraron los documentos cartográficos y programas de manejo de las ANP Humedales La Libertad, del municipio Desarrollo de La Libertad y Humedales de Montaña María Eugenia, del municipio de San Cristóbal de las Casas. Sustentable SUBFUNCIÓN: ADMINISTRACIÓN DEL AGUA ENTIDAD: INSTITUTO ESTATAL DEL AGUA PRINCIPALES ACCIONES Y RESULTADOS Proyecto: Programa Agua Limpia 2010. Con la finalidad de abatir enfermedades de origen hídrico, se realizaron 83 instalaciones de equipos de desinfección en los municipios de Amatán, Chalchihuitán, Chamula, Huitiupán, Mitontic, Oxchuc y San Cristóbal de las Casas, entre otros; asimismo, se repusieron 31 equipos de desinfección en los municipios de Cintalapa, Frontera Comalapa, La Concordia, Pichucalco y Reforma, entre otros; además se instalaron 627 equipos rústicos de desinfección en los municipios de Chanal, Huixtán, Oxchuc y San Juan Cancúc; así también, se realizaron 2,218 monitoreos de cloro residual, además se llevo a cabo el suministro de 410 toneladas de hipoclorito de calcio y 209 piezas de ión plata, en diversos municipios del Estado; de igual manera se efectuaron 10 operativo de saneamiento en los municipios de Yajalón, Suchiapa, Soyaló, entre otros. -

CHIAPAS En Chiapas La Población Indígena Es Equivalente a 957,255

CHIAPAS En Chiapas la población indígena es equivalente a 957,255 que representan el 26% de la población total, habitando principalmente en los municipios de Ocosingo, San Cristóbal de las Casas, Chilón, Chamula, Tila, Las Margaritas, Salto de Agua, Palenque, Oxchuc, Tenejaba, Zinacantan, Tumbalá, Chenalhó, Tuxtla Gutiérrez y Yajalón. Las lenguas indígenas que predominan en el Estado son Tzotzil 36%, Tzetzal 34.4% y Chol 17.4%. 5% 2% 0% 5% 37% 17% 34% Tzotzil Tzeltal Chol Zoque Tojolabal Otras lenguas indígenas en México No especificado Fuente: II Conteo de Población y Vivienda 2005. De acuerdo a la población de 5 y más años por condición de habla indígena y habla española, en Chiapas el 61.2% habla español, mientras que el 36.5% solo habla su lengua materna. En el Estado un 40.2% de la población indígena no recibe ningún ingreso, y el 42% recibe menos de un salario mínimo. La religión que predomina en la población indígena de la entidad es la católica con 54.2%, seguida de las religiones protestantes y evangélicas con un 23.7%. Población de 5 y más años. No habla Habla No Municipio Total lengua lengua especificado indígena indígena Chiapas 3,677,979 2,707,443 957,255 13,281 Acacoyagua 12,935 12,848 46 41 Acala 22,942 20,193 2,680 69 Acapetahua 21,464 21,361 57 46 Aldama 3,465 3 3,461 1 Altamirano 18,560 5,866 12,660 34 Amatán 17,012 14,267 2,664 81 Amatenango de la 22,301 21,759 509 33 Frontera Amatenango del Valle 5,887 1,313 4,568 6 Angel Albino Corzo 20,876 20,120 674 82 Arriaga 34,032 33,667 259 106 Bejucal de Ocampo 5,634 5,546 -

XXIII.- Estadística De Población

Estadística de Población Capítulo XXIII Estadística de Población La estadística de población tiene como finalidad apoyar a los líderes de proyectos en la cuantificación de la programación de los beneficiarios de los proyectos institucionales e inversión. Con base a lo anterior, las unidades responsables de los organismos públicos contaran con elementos que faciliten la toma de decisiones en el registro de los beneficiarios, clasificando a la población total a nivel regional y municipal en las desagregaciones siguientes: Género Hombre- Mujer Ubicación por Zona Urbana – Rural Origen Poblacional Mestiza, Indígena, Inmigrante Grado Marginal Muy alto, Alto, Medio, Bajo y Muy Bajo La información poblacional para 2014 se determinó con base a lo siguiente: • Los datos de población por municipio, se integraron con base a las proyecciones 2010 – 2030, publicados por el Consejo Nacional de Población (CONAPO): población a mitad de año por sexo y edad, y población de los municipios a mitad de año por sexo y grupos de edad. • El grado marginal, es tomada del índice y grado de marginación, lugar que ocupa Chiapas en el contexto nacional y estatal por municipio, emitidos por el CONAPO. • Los datos de la población indígena, fueron determinados acorde al porcentaje de población de 3 años y más que habla lengua indígena; emitidos por el Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), en el Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010; multiplicada por la población proyectada. • Los datos de la clasificación de población urbana y rural, se determinaron con base al Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010, emitido por el INEGI; considerando como población rural a las personas que habitan en localidades con menos de 2,500 habitantes. -

Xhcom-Tdt Comitan De Dominguez

Entidad Municipio Localidad Long Lat Chiapas Altamirano EL ARBOLITO 914540 163018 Chiapas Altamirano EL CALVARIO 914350 163116 Chiapas Altamirano GETZEMANÍ 914609 163039 Chiapas Altamirano NUEVO TULIPÁN 914545 163055 Chiapas Altamirano PALESTINA 914552 163035 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera AGUA ESCONDIDA 921059 153324 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera EL BAÑADERO 920916 153220 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera EL ZAPOTE 920903 153207 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera ESCOBILLAL 920827 153211 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera FRANCISCO I. MADERO 920519 153050 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera LA LAGUNITA 920607 152913 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera LA MESILLA 920938 153255 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera LAS CRUCES 920208 153445 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera MONTE ORDÓÑEZ 921017 153342 Amatenango de la Chiapas Frontera SAN JOSÉ DE LOS POZOS 920342 153146 Chiapas Amatenango del Valle CANDELARIA BUENAVISTA 921921 162904 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LA TARRAYA 923128 154105 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LAS BRISAS 923123 154105 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LAS PIMIENTILLAS 923355 153847 Chiapas Angel Albino Corzo LOMA BONITA 923351 153831 Chiapas Bejucal de Ocampo EL LIMÓN 921153 152754 Chiapas Bejucal de Ocampo JUSTO SIERRA 921045 153244 Chiapas Bejucal de Ocampo LA SOLEDAD 920949 153129 Chiapas Bella Vista ALLENDE 921325 153917 Chiapas Bella Vista BUENAVISTA 921735 153443 Chiapas Bella Vista EL PARAÍSO 921215 153329 Chiapas Bella Vista LA AVANZADA 921430 153939 Chiapas Bella Vista LA LAGUNA 921845 153455 Chiapas Bella Vista LA LUCHA -

CHIAPAS* Municipios Entidad Tipo De Ente Público Nombre Del Ente Público

Inventario de Entes Públicos CHIAPAS* Municipios Entidad Tipo de Ente Público Nombre del Ente Público Chiapas Municipio 07-001 Acacoyagua Chiapas Municipio 07-002 Acala Chiapas Municipio 07-003 Acapetahua Chiapas Municipio 07-004 Altamirano Chiapas Municipio 07-005 Amatán Chiapas Municipio 07-006 Amatenango de la Frontera Chiapas Municipio 07-007 Amatenango del Valle Chiapas Municipio 07-008 Ángel Albino Corzo Chiapas Municipio 07-009 Arriaga Chiapas Municipio 07-010 Bejucal de Ocampo Chiapas Municipio 07-011 Bella Vista Chiapas Municipio 07-012 Berriozábal Chiapas Municipio 07-013 Bochil * Inventario elaborado con información del CACEF y EFSL. 19 de marzo de 2020 Inventario de Entes Públicos ChiapasCHIAPAS* Municipio 07-014 El Bosque Chiapas Municipio 07-015 Cacahoatán Chiapas Municipio 07-016 Catazajá Chiapas Municipio 07-017 Cintalapa Chiapas Municipio 07-018 Coapilla Chiapas Municipio 07-019 Comitán de Domínguez Chiapas Municipio 07-020 La Concordia Chiapas Municipio 07-021 Copainalá Chiapas Municipio 07-022 Chalchihuitán Chiapas Municipio 07-023 Chamula Chiapas Municipio 07-024 Chanal Chiapas Municipio 07-025 Chapultenango Chiapas Municipio 07-026 Chenalhó Chiapas Municipio 07-027 Chiapa de Corzo Chiapas Municipio 07-028 Chiapilla Chiapas Municipio 07-029 Chicoasén Inventario de Entes Públicos ChiapasCHIAPAS* Municipio 07-030 Chicomuselo Chiapas Municipio 07-031 Chilón Chiapas Municipio 07-032 Escuintla Chiapas Municipio 07-033 Francisco León Chiapas Municipio 07-034 Frontera Comalapa Chiapas Municipio 07-035 Frontera Hidalgo Chiapas -

Chiapas. Formato Estatus SIPINNA Municipales 280520.Xlsx

No. ENTIDAD FEDERATIVA MUNICIPIO NOMBRE COMPLETO CARGO INSTITUCIÓN CORREO ELECTRÓNICO TELÉFONO OFICINA TELÉFONO CELULAR DOMICILIO DE LA SECRETARÍA EJECUTIVA SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DEL SISTEMA DE SECRETARÍA AV. MIGUEL HIDALGO S/N, COL. CENTRO, C.P. 30590, 1 CHIAPAS ACACOYAGUA LIC. GABRIEL CRUZ ANTONIO PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y [email protected] S/N 9181107511 MUNICIPAL ACACOYAGUA, CHIAPAS ADOLESCENTES DEL MUNICIPIO DE ACACOYAGUA SECRETARIA EJECUTIVA DEL SISTEMA DE SECRETARÍA AV. GRIJALVA S/N, ENTRE CALLE CORONEL RUIZ, BARRIO 2 CHIAPAS ACALA LIC. SANDI JAZMÍN GÓMEZ FRANCO PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y [email protected] S/N 9611878712 MUNICIPAL SAN PABLO, C.P. 29370 ACALA, CHIAPAS ADOLESCENTES DEL MUNICIPIO DE ACALA SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DEL SISTEMA DE 3 CHIAPAS ACAPETAHUA SIN NOMBRAMIENTO PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y ADOLESCENTES DEL MUNICIPIO DE ACAPETAHUA SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DEL SISTEMA DE SECRETARÍA CENTRAL S/N., COL. CENTRO, C.P. 29870, ALDAMA, 4 CHIAPAS ALDAMA LIC. EMETERIO DÍAZ RUIZ PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y [email protected] S/N 9671274223 MUNICIPAL CHIAPAS ADOLESCENTES DEL MUNICIPIO DE ALDAMA SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DEL SISTEMA DE 5 CHIAPAS ALTAMIRANO SIN NOMBRAMIENTO PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y ADOLESCENTES DEL MUNICIPIO DE ALTAMIRANO SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DEL SISTEMA DE DEPARTAMENTO 6 CHIAPAS AMATÁN LIC. FLORIBERTO LÓPEZ MARTÍNEZ PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y [email protected] S/N 9191446979 CENTRAL S/N, COL. CENTRO, C.P. 29700, AMATÁN, JURÍDICO ADOLESCENTES DEL MUNICIPIO DE AMATÁN SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DEL SISTEMA DE PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y 7 CHIAPAS AMATENANGO DE LA FRONTERA SIN NOMBRAMIENTO ADOLESCENTES DEL MUNICIPIO DE AMATENANGO DE LA FRONTERA SECRETARIO EJECUTIVO DEL SISTEMA DE PROTECCCIÓN INTEGRAL DE NIÑAS, NIÑOS Y H. -

Resolutivo De La Comisión Nacional De Elecciones

RESOLUTIVO DE LA COMISIÓN NACIONAL DE ELECCIONES SOBRE EL PROCESO INTERNO LOCAL DEL ESTADO DE CHIAPAS (LISTA APROBADA DE REGISTROS PARA LAS CANDIDATURAS DE SÍNDICOS) México DF., a 22 de mayo de 2015 De conformidad con lo establecido en el Estatuto de Morena y la Convocatoria para la selección de candidaturas para diputadas y diputados al Congreso del estado por el principio de mayoría relativa, así como de presidentes municipales y síndicos para el proceso electoral 2015 en el estado de Chiapas; la Comisión Nacional de Elecciones de Morena da a conocer la relación de solicitudes de registro aprobadas: SÍNDICOS: NUM. MUNICIPIO A. PATERNO A. MATERNO NOMBRE (S) 1 ACACOYAGUA NISHIZAWA RABANALES CESAR 2 ACALA 3 ACAPETAHUA 4 ALDAMA 5 ALTAMIRANO 6 AMATAN AMATENANGO DE LA 7 FRONTERA 8 AMATENANGO DEL VALLE 9 ANGEL ALBINO CORZO 10 ARRIAGA ESCOBAR DIAZ LUZ PATRICIA 11 BEJUCAL DE OCAMPO 12 BELISARIO DOMINGUEZ 13 BELLAVISTA BENEMERITO DE LAS 14 AMERICAS GOMEZ SANTOS CELINA 15 BERRIOZABAL 16 BOCHIL HERNANDEZ DIAZ MARIA DEL ROSARIO 17 CACAHOATAN MORALES RAMIREZ VELIA MATILDE 18 CATAZAJA 19 CHALCHIHUITAN 20 CHAMULA 21 CHANAL 22 CHAPULTENANGO 23 CHENALHO PEREZ GUTIERREZ JUANA 24 CHIAPA DE CORZO PAVÓN PEREZ SARA 25 CHIAPILLA 26 CHICOASEN 27 CHICOMUSELO GARCIA PEREZ HIPOLITA 28 CHILON 29 CINTALAPA CRUZ MORALES JEZIKA 30 COAPILLA SANCHEZ LOPEZ MARIA FLOR 31 COMITAN DE DOMINGUEZ 32 COPAINALA MORALES TOVILLA IRENE LULU 33 EL BOSQUE 34 EL PORVENIR MORALES MEJIA ENRIQUETA MELINA 35 EMILIANO ZAPATA 36 ESCUINTLA 37 FRANCISCO LEON 38 FRONTERA COMALAPA PEREZ CASTILLEJOS