Why Teams Don't Work What Goes Wrong, and How to Make It Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys

Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys,Wild Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps on sale! you get multiple choices!On Discount now!By: Robert Rilesl ,2012 nike nfl jerseys Sports and Fitness> Hockeyl Dec 26,authentic nhl jersey, 2007 lViews: 102 Sports Collectible ¡§C What your family Must Have to ensure they are Cool Sports prized possessions are goodies that every sports delicacies not only can they want for more information regarding be capable of geting their hands on There are private sports antique stores all over the globe during which time one or more can feast their eyes all over the their team gears,cheap nfl authentic jerseys,foot wear or at best several apparels worn judging by then during the match, and also find autographed balls and bats in the air as well as for sale. By: Robert Rilesl Sports and Fitnessl Dec 22,make your own hockey jersey, 2007 Mcdonald?¡¥s Hockey Collectibles: Building More Interest everywhere in the Hockey Memorabilia Hockey trading cards may seem to wane in popularity,personalized basketball jerseys,but if McDonald?¡¥s has its way,element won?¡¥t be the case as well as during a period 100 a long time They may probably have effortless spikes all around the demand thanks for more information about McDonald?¡¥s playing tennis collectibles These racket sports cards that come from the prior to buying having to do with Ronald McDonald are actually worth something,jersey baseball,considering that it?¡¥s supplied one of the most all over the Canada and that several different kids actually don?¡¥t think much concerning them, leaving much of the loot and short span of time offer the for more information on down and dirty collectors. -

Dallas Mavericks (42-30) (3-3)

DALLAS MAVERICKS (42-30) (3-3) @ LA CLIPPERS (47-25) (3-3) Game #7 • Sunday, June 6, 2021 • 2:30 p.m. CT • STAPLES Center (Los Angeles, CA) • ABC • ESPN 103.3 FM • Univision 1270 THE 2020-21 DALLAS MAVERICKS PLAYOFF GUIDE IS AVAILABLE ONLINE AT MAVS.COM/PLAYOFFGUIDE • FOLLOW @MAVSPR ON TWITTER FOR STATS AND INFO 2020-21 REG. SEASON SCHEDULE PROBABLE STARTERS DATE OPPONENT SCORE RECORD PLAYER / 2020-21 POSTSEASON AVERAGES NOTES 12/23 @ Suns 102-106 L 0-1 12/25 @ Lakers 115-138 L 0-2 #10 Dorian Finney-Smith LAST GAME: 11 points (3-7 3FG, 2-2 FT), 7 rebounds, 4 assists and 2 steals 12/27 @ Clippers 124-73 W 1-2 F • 6-7 • 220 • Florida/USA • 5th Season in 42 minutes in Game 6 vs. LAC (6/4/21). NOTES: Scored a playoff career- 12/30 vs. Hornets 99-118 L 1-3 high 18 points in Game 1 at LAC (5/22/21) ... hit GW 3FG vs. WAS (5/1/21) 1/1 vs. Heat 93-83 W 2-3 GP/GS PPG RPG APG SPG BPG MPG ... DAL was 21-9 during the regular season when he scored in double figures, 1/3 @ Bulls 108-118 L 2-4 6/6 9.0 6.0 2.2 1.3 0.3 38.5 1/4 @ Rockets 113-100 W 3-4 including 3-1 when he scored 20+. 1/7 @ Nuggets 124-117* W 4-4 #6 LAST GAME: 7 points, 5 rebounds, 3 assists, 3 steals and 1 block in 31 1/9 vs. -

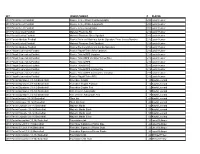

2003 - 2004 Roster

As of 11/19 2003 - 2004 ROSTER Team: JKnights 1 Team: Rainbows 2 Team: Madman 3 Owner: Isaac Owner: Carl Owner: Nathan NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM Kevin Garnett F Timberwolves Tim Duncan C Spurs Shaquille O'Neal C Lakers Ray Allen G Supersonics Shawn Marion F Suns Allen Iverson G 76ers Jermaine O'Neal C Pacers Steve Francis G Rockets Amare Stoudemire F Suns Vince Carter G Raptors Jason Terry G Hawks Steve Nash G Mavericks Gilbert Arenas G Wizards Ricky Davis F Cavaliers Jerry Stackhouse G Wizards Andrei Kirilenko F Jazz Donyell Marshall F Bulls Lamar Odom F Heat Predrag Stojakovic F Kings Jason Williams G Grizzlies Kurt Thomas C Knicks Jamal Crawford G Bulls Juwan Howard F Magic Michael Redd G Bucks Theo Ratliff C Hawks Eric Snow G 76ers Shane Battier F Grizzlies Ron Artest F Pacers Jamaal Magloire C Hornets Matt Harpring F Jazz Team: Wasabi Belly 4 Team: Blank 5 Team: Loose Screw 6 Owner: Randall Owner: Chris Owner: Keith NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM NAME POS TEAM Dirk Nowitzki C Mavericks Tracy McGrady G Magic Paul Pierce G Celtics Elton Brand F Clippers Ben Wallace C Pistons Baron Davis G Hornets Gary Payton G Lakers Stephon Marbury G Suns Yao Ming C Rockets Shareef Abdur Rahim F Hawks Pau Gasol F Grizzlies Chris Webber F Kings Sam Cassell G Timberwolves Jamal Mashburn F Hornets Drew Gooden F Magic Zydrunas Ilgauskas C Cavaliers Rasheed Wallace F Trailblazers Caron Butler F Heat Brian Grant F Heat Jalen Rose G Bulls Michael Finley G Mavericks Jamaal Tinsley G Pacers Chauncey Billups G Pistons Rashard Lewis F Supersonics Troy Murphy F Warriors Alonzo Mourning C Nets Antonio Davis C Raptors Jason Richardson G Warriors Glenn Robinson F 76ers Anthony Carter G Spurs Team: Ctity Worker 7 Owner: Eric NAME POS TEAM Kobe Bryant F Lakers Jason Kidd G Nets LeBron James G Cavaliers Carmelo Anthony F Nuggets Michael Olowokandi C Timberwolves Karl Malone F Lakers Andre Miller G Nuggets Antoine Walker F Mavericks Kenyon Martin F Nets Brad Miller C Kings. -

WISCONSIN Basketball

WISCONSIN basketball 23 NCAA Tournaments ▪ 4 Final Fours (1941, 2000, 2014, 2015) ▪ 18 Big Ten Championships ▪ 21 Consensus All-Americans 2018-19 SCHEDULE WISCONSIN 30, 00 VS. STANFORD 21, 00 NOV. 21, 2018 ▪ 1:30 PM CT ▪ PARADISE ISLAND, BAHAMAS ▪ IMPERIAL BALLROOM ▪ ESPN Date Opponent Time WISCONSIN BADGERS TV . .ESPN NOV. 6 COPPIN STATE W, 85-63 Rankings (AP/Coaches) RV/RV (Jon Sciambi & Dan Dakich) Nov. 13 at Xavier (Gavi Games) W, 77-68 Head Coach: Greg Gard Radio . Badger Radio Network NOV. 17 HOUSTON BAPTIST W, 96-59 Record at WIS: 60-36 (4th) (Jon Arias & Andy North) Overall: 60-36 (4th) GAME 4 All-Time Series. SU lead, 6-3 2018 Ba le 4 Atlan s - Paradise Island, Bahamas STANFORD CARDINAL All-Time at Nuetral . First Meeting Nov. 21 vs. Stanford 1:30 pm Rankings (AP/Coaches) --/-- Nov. 22 vs. Florida/Oklahoma Head Coach: Jerod Haase Last Meeting . SU won, 95-78, in Palo Alto, Calif. (12/27/94) Nov. 23 vs. Butler/Dayton/MTSU/Virginia [4] Record at SU: 35–34 (3rd) Overall: 115-87 (7th) Active Streak . .SU won last 1 NOV. 27 NC STATE (B1G/ACC Challenge) 8 pm Nov. 30 at Iowa 7 pm UW RETURNS TO BATTLE 4 ATLANTIS Wisconsin will return to the Bahamas looking to repeat DEC. 3 RUTGERS 7 pm their 2014 Battle 4 Atlantis Championship. The Badgers Dec. 8 at Marque e [24] 4 pm will play their first of 3 games against Stanford on Wed., DEC. 13 SAVANNAH STATE 7 pm Nov. 21 before facing either Florida or Oklahoma. -

Why Change Doesn't Work

WHY CHANGE DOESN'T WORK Why Initiatives Go Wrong, And How to Try Again -- and Succeed by Harvey Robbins and Michael Finley redline version 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgments 5 Introduction 8 11 PART 1 Life in the Blender What this book is about 14 The High Cost of Change Failures 16 Of Babies and Bathwater 18 Some Discarded Babies 21 Four Approaches 25 ‰ PUMMEL 26 ‰ PAMPER 28 ‰ PUSH 29 ‰ PULL 32 Combining the Four Approaches 34 The Meaning of Meaning 37 Why Change Fails 39 Why We're Hurting, and What We Must Do 45 47 PART 2 The Problem with People Change and the brain 51 Right Brains and Left Brains 54 Human Variation 56 Change and Personality 58 Building the Personality Matrix 61 ‰ ASSESSING INDIVIDUALS 67 72 Part 3 Why Groups Don't Work Assessing the Organization 73 ‰ THE ORGANIZATIONAL PROFILE 74 Change and Unreason 76 Rebalancing the Stress Load 79 Expanding the Change Space 82 Seven Hard Truths 84 87 PART 4 Making Change Hub and Spoke Planning 87 Introducing Change 89 What You Can Do and What You Can't Do 90 The Best Way to Change 93 The Best Time to Change 94 Big Change Versus Little Changes 96 Crossing the Swamp 99 Organizational Shame 101 Igniting Organizational Imagination 104 Overcoming Resistance 110 The Roles of the Changemaker 112 ‰ THE CHANGEMAKER AS PATHMAKER 112 ‰ THE CHANGEMAKER AS INTEGRATOR 113 ‰ THE CHANGEMAKER AS NEGOTIATOR 114 ‰ THE CHANGEMAKER AS GAME PLAYER 116 ‰ THE CHANGEMAKER AS CONFESSOR 117 ‰ THE CHANGEMAKER AS SALES PERSON 117 ‰ THE CHANGEMAKER AS STAGE MANAGER 118 Hiring Good People 119 -

Actual Vs. Perceived Value of Players of the National Basketball Association

Actual vs. Perceived Value of Players of the National Basketball Association BY Stephen Righini ADVISOR • Alan Olinsky _________________________________________________________________________________________ Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors in the Bryant University Honors Program APRIL 2013 Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ...........................................................................................................................2 How NBA MVPs Are Determined .....................................................................................2 Reason for Selecting This Topic ........................................................................................2 Significance of This Study .................................................................................................3 Thesis and Minor Hypotheses ............................................................................................4 Player Raters and Perception Factors .....................................................................................5 Data Collected ...................................................................................................................5 Perception Factors .............................................................................................................7 Player Raters .........................................................................................................................9 -

Set Insert/Subset # Player

SET INSERT/SUBSET # PLAYER 2013 Panini Select Football Rookie Jersey Prizm Gold Autographs 202 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Select Football Rookie Jersey Prizm Autographs 202 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Select Football Rookie Jersey Autographs 202 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Limited Football Material Phenoms RC 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Limited Football Material Phenoms Silver Spotlight 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Absolute Football Rookie Premiere Materials Jumbo Signature Prime Jersey Number 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Limited Football Material Phenoms Gold Spotlight 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Absolute Football Rookie Premiere Materials Jumbo Signature 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Playoff Ticket RPS Variation 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Tickets RPS Variation 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Ticket RPS Variation Yellow Plate 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Tickets RPS 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Tickets RPS 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Tickets RPS Cracked Ice 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Tickets RPS Cracked Ice Variation 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Playoff Contenders Football Rookie Playoff Ticket RPS 216 Justin Hunter 2013 Panini Signatures (13-14) Basketball Franchise Graphs 12 Kawhi Leonard 2013 Panini Signatures (13-14) Basketball Franchise Graphs Platinum 12 Kawhi Leonard 2013 Panini Signatures (13-14) Basketball Franchise Graphs Red 12 -

When Is a Basket Not a Basket? the Basket Either Was Made Before the Clock Expired Or Nswer: When 3 the Protest by After

“Local name, national Perspective” $3.95 © Volume 4 Issue 6 NBA PLAYOFFS SPECIAL April 1998 BASKETBALL FOR THOUGHT by Kris Gardner, e-mail: [email protected] A clock was involved; not a foul or a violation of the rules. When is a Basket not a Basket? The basket either was made before the clock expired or nswer: when 3 The protest by after. The clock provides tan- officials and deter- the losing gible proof. This wasn’t a commissioner mina- team. "The charge or block call. Period. David Stern tion as Board of No gray area here. say so. to Governors Secondly, it’s time the Sunday, April 12, the whethe has not league allows officials to use Knicks apparently defeated r a ball seen fit to replay when dealing with is- the Miami Heat 83 - 82, on a is shot adopt such sues involving the clock. It’s last second rebound by G prior a rule," the sad that the entire viewing Allan Houston. Replays to the Commis- audience could see replays showed Allan scored the bas- expira- sioner showing the basket should be ket with 2 tenths of a second tion of stated, allowed and not the 3 most on the clock. However, offi- time, "although important people—the refer- cials disagreed. They hud- Stern © ees calling the game! Ironi- dled after the shot for 30 "...although the subject has been considered from time to cally, the officials viewed the seconds to determine if they time. Until it does so, such is not the function of the replays in the locker after the were all in agreement. -

MA#12Jumpingconclusions Old Coding

Mathematics Assessment Activity #12: Mathematics Assessed: · Ability to support or refute a claim; Jumping to Conclusions · Understanding of mean, median, mode, and range; · Calculation of mean, The ten highest National Basketball League median, mode and salaries are found in the table below. Numbers range; like these lead us to believe that all professional · Problem solving; and basketball players make millions of dollars · Communication every year. While all NBA players make a lot, they do not all earn millions of dollars every year. NBA top 10 salaries for 1999-2000 No. Player Team Salary 1. Shaquille O'Neal L.A. Lakers $17.1 million 2. Kevin Garnett Minnesota Timberwolves $16.6 million 3. Alonzo Mourning Miami Heat $15.1 million 4. Juwan Howard Washington Wizards $15.0 million 5. Patrick Ewing New York Knicks $15.0 million 6. Scottie Pippen Portland Trail Blazers $14.8 million 7. Hakeem Olajuwon Houston Rockets $14.3 million 8. Karl Malone Utah Jazz $14.0 million 9. David Robinson San Antonio Spurs $13.0 million 10. Jayson Williams New Jersey Nets $12.4 million As a matter of fact according to data from USA Today (12/8/00) and compiled on the website “Patricia’s Basketball Stuff” http://www.nationwide.net/~patricia/ the following more accurately reflects the salaries across professional basketball players in the NBA. 1 © 2003 Wyoming Body of Evidence Activities Consortium and the Wyoming Department of Education. Wyoming Distribution Ready August 2003 Salaries of NBA Basketball Players - 2000 Number of Players Salaries 2 $19 to 20 million 0 $18 to 19 million 0 $17 to 18 million 3 $16 to 17 million 1 $15 to 16 million 3 $14 to 15 million 2 $13 to 14 million 4 $12 to 13 million 5 $11 to 12 million 15 $10 to 11 million 9 $9 to 10 million 11 $8 to 9 million 8 $7 to 8 million 8 $6 to 7 million 25 $5 to 6 million 23 $4 to 5 million 41 3 to 4 million 92 $2 to 3 million 82 $1 to 2 million 130 less than $1 million 464 Total According to this source the average salaries for the 464 NBA players in 2000 was $3,241,895. -

DPW PH 05 Layout 1

präsentiert Regie Sebastian Dehnhardt mit Dirk Nowitzki Holger Geschwindner Kobe Bryant, Michael Finley, Steve Nash, Jason Kidd, Vince Carter, Mark Cuban, Don Nelson, Donnie Nelson, Rick Carlisle, David Stern, Helga Nowitzki, Jörg-Werner Nowitzki, Silke Nowitzki, Jessica Nowitzki und Bundeskanzler a.D. Helmut Schmidt Eine Produktion von BROADVIEW PICTURES In Co-Produktion mit WDR und BR Produzent Leopold Hoesch Produziert mit Förderung von Film- und Medienstiftung NRW Deutscher Filmförderfonds Filmförderungsanstalt Kinostart: 18. September 2014 Im Verleih von NFP marketing & distribution* Im Vertrieb von Tobis Film VERLEIH NFP marketing & distribution* Kantstraße 54 | 10627 Berlin Tel. 030 – 232 55 42 13 www.NFP.de VERTRIEB TOBIS FILM GmbH & Co. KG Kurfürstendamm 63 | 10707 Berlin Tel. 030 – 839 007 0 www.tobis.de PRESSEBETREUUNG boxfish films Raumerstraße 27 | 10437 Berlin Tel. 030 – 44044 753 / -691 E-Mail: [email protected] Weitere Presseinformationen und Bildmaterial stehen online für Sie bereit unter www.filmpresskit.de 3 INHALT PRESSENOTIZ 4 SYNOPSIS 6 Ein Wurf von gestern nach heute 6 Treffen der Generationen 6 Gegen jeden Zweifel 6 Im kalten Wasser 7 Krisenzeiten 8 Die perfekte Saison 9 DIE PROTAGONISTEN 11 Dirk Nowitzki 11 Holger Geschwindner 12 AUSFLÜGE 13 Ein paar Jumps durch die Geschichte des Basketballs 13 Neue Regeln, neues Glück 13 White Prince, big hope 14 Die richtige Technik 14 Basketball und Jazz 15 Die Playoffs 16 DAS PRODUKTIONSTAGEBUCH – PENDELN ZWISCHEN ZWEI POLEN 17 Transatlantischer Austausch 17 Das Horrorhotel 18 In der Arena 19 Die Story freilegen 19 INTERVIEWS 21 mit Regisseur Sebastian Dehnhardt 21 mit Produzent Leopold Hoesch 24 DIE CREW 26 Sebastian Dehnhardt – Regie 26 Johannes Imdahl – Kamera 26 André Hammesfahr – Schnitt 26 Stefan Ziethen – Musik 27 Leopold Hoesch – Produzent 27 BROADVIEW PICTURES – Produktion 27 DIE PERSONEN 29 DER STAB 30 TECHNISCHE ANGABEN 30 4 PRESSENOTIZ Zum Film: 13 Jahre lang kämpft Dirk Nowitzki um die Trophäe aller Trophäen. -

June 1998: NBA Draft Special

“Local name, national Perspective” $4.95 © Volume 4 Issue 8 1998 NBA Draft Special June 1998 BASKETBALL FOR THOUGHT by Kris Gardner, e-mail: [email protected] Garnett—$126 M; and so on. Whether I’m worth the money Lockout, Boycott, So What... or not, if someone offered me one of those contract salaries, ime is ticking by patrio- The I’d sign in a heart beat! (Right and July 1st is tism in owners Jim McIlvaine!) quickly ap- 1992 want a In order to compete with proaching. All when hard the rising costs, the owners signs point to the owners he salary cap raise the prices of the tickets. locking out the players wore with no Therefore, as long as people thereby delaying the start of the salary ex- buy the tickets, the prices will the free agent signing pe- Ameri- emptions continue to rise. Hell, real riod. As a result of the im- can similar to people can’t afford to attend pending lockout, the players flag the NFL’s games now; consequently, union has apparently de- draped salary cap corporations are buying the cided to have the 12 mem- over and the seats and filling the seats with bers selected to represent the his players suits. USA in this summer’s World Team © The players have wanted Championships in Greece ...the owners were rich when they entered the league and to get rid of the salary cap for boycott the games. Big deal there aren’t too many legal jobs where tall, athletic, and, in years and still maintain that and so what. -

2013-14 Panini Prestige HITS Checklist Basketball

2013-14 Panini Prestige HITS Checklist Basketball 76ers Player Set # Team Seq # Andrew Bynum Frequent Flyer Autographs 22 76ers 49 Andrew Bynum Hoopla Autographs 38 76ers 25 Andrew Bynum Iconic Autographs 37 76ers 25 Bobby Jones Old School Signatures 50 76ers 99 Derrick Coleman Bonus Shots Autographs 52 76ers - Derrick Coleman Bonus Shots Blue Autographs 52 76ers 99 Derrick Coleman Bonus Shots Gold Autographs 52 76ers 10 Derrick Coleman Bonus Shots Green Autographs 52 76ers 5 Derrick Coleman Bonus Shots Platinum Autographs 52 76ers 1 Derrick Coleman Bonus Shots Red Autographs 52 76ers 25 Dikembe Mutombo Bonus Shots Autographs 81 76ers - Dikembe Mutombo Bonus Shots Blue Autographs 81 76ers 49 Dikembe Mutombo Bonus Shots Gold Autographs 81 76ers 10 Dikembe Mutombo Bonus Shots Green Autographs 81 76ers 5 Dikembe Mutombo Bonus Shots Platinum Autographs 81 76ers 1 Dikembe Mutombo Bonus Shots Red Autographs 81 76ers 25 Dolph Schayes Old School Signatures 52 76ers 10 Evan Turner Bonus Shots Materials 73 76ers - Evan Turner Bonus Shots Prime Materials 73 76ers 25 Evan Turner True Colors Materials 63 76ers - Evan Turner True Colors Prime Materials 63 76ers 25 George McGinnis Old School Signatures 17 76ers 99 Hal Greer Old School Signatures 19 76ers 50 Henry Bibby Old School Signatures 47 76ers 99 Jason Richardson Bonus Shots Materials 75 76ers - Jason Richardson Bonus Shots Prime Materials 75 76ers 25 Jason Richardson True Colors Materials 28 76ers - Jason Richardson True Colors Prime Materials 28 76ers 25 Lavoy Allen True Colors Materials 70