Heterogeneous Versus Homogeneous Measures: a Meta-Analysis of Predictive Efficacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Validity of Reading Assessments GOTHENBURG STUDIES in EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES 328

On the Validity of Reading Assessments GOTHENBURG STUDIES IN EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES 328 On the Validity of Reading Assessments Relationships Between Teacher Judgements, External Tests and Pupil Self-assessments Stefan Johansson ACTA UNIVERSITATIS GOTHOBURGENSIS LOGO GOTHENBURG STUDIES IN EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES 328 On the Validity of Reading Assessments Relationships Between Teacher Judgements, External Tests and Pupil Self-assessments Stefan Johansson ACTA UNIVERSITATIS GOTHOBURGENSIS LOGO © STEFAN JOHANSSON, 2013 ISBN 978-91-7346-736-0 ISSN 0436-1121 ISSN 1653-0101 Thesis in Education at the Department of Education and Special Education The thesis is also available in full text on http://hdl.handle.net/2077/32012 Photographer cover: Rebecka Karlsson Distribution: ACTA UNIVERSITATIS GOTHOBURGENSIS Box 222 SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Print: Ale Tryckteam, Bohus 2013 Abstract Title: On the Validity of Reading Assessments: Relationships Between Teacher Judgements, External Tests and Pupil Self-assessments Language: English with a Swedish summary Keywords: Validity; Validation; Assessment; Teacher judgements; External tests; PIRLS 2001; Self-assessment; Multilevel models; Structural Equation Modeling; Socioeconomic status; Gender ISBN: 978-91-7346-736-0 The purpose of this thesis is to examine validity issues in different forms of assessments; teacher judgements, external tests, and pupil self-assessment in Swedish primary schools. The data used were selected from a large-scale study––PIRLS 2001––in which more than 11000 pupils and some 700 teachers from grades 3 and 4 participated. The primary method used in the secondary analyses to investigate validity issues of the assessment forms is multilevel Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with latent variables. An argument-based approach to validity was adopted, where possible weaknesses in assessment forms were addressed. -

Questionnaire Validity and Reliability

Questionnaire Validity and reliability Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Outlines Introduction What is validity and reliability? Types of validity and reliability. How do you measure them? Types of Sampling Methods Sample size calculation G-Power ( Power Analysis) Research • The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions • In the broadest sense of the word, the research includes gathering of data in order to generate information and establish the facts for the advancement of knowledge. ● Step I: Define the research problem ● Step 2: Developing a research plan & research Design ● Step 3: Define the Variables & Instrument (validity & Reliability) ● Step 4: Sampling & Collecting data ● Step 5: Analysing data ● Step 6: Presenting the findings A questionnaire is • A technique for collecting data in which a respondent provides answers to a series of questions. • The vehicle used to pose the questions that the researcher wants respondents to answer. • The validity of the results depends on the quality of these instruments. • Good questionnaires are difficult to construct; • Bad questionnaires are difficult to analyze. •Identify the goal of your questionnaire •What kind of information do you want to gather with your questionnaire? • What is your main objective? • Is a questionnaire the best way to go about collecting this information? Ch 11 6 How To Obtain Valid Information • Ask purposeful questions • Ask concrete questions • Use time periods -

Running Head: the STRUCTURE of PSYCHOPATHIC PERSONALITY 1 Evaluating the Structure of Psychopathic Personality Traits: a Meta-An

Running head: THE STRUCTURE OF PSYCHOPATHIC PERSONALITY 1 Evaluating the Structure of Psychopathic Personality Traits: A Meta-Analysis of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory Jared R. Ruchensky, John F. Edens, Katherine S. Corker, M. Brent Donnellan, Edward A. Witt, Daniel M. Blonigen Version: 11/17/2017 In press, Psychological Assessment © 2017, American Psychological Association. This paper is not the copy of record and may not exactly replicate the final, authoritative version of the article. The final article will be available, upon publication, via its DOI: 10.1037/pas0000520 THE STRUCTURE OF PSYCHOPATHIC PERSONALITY 2 Abstract Which core traits exemplify psychopathic personality disorder is a hotly debated question within psychology, particularly regarding the role of ostensibly adaptive traits such as stress immunity, social potency, and fearlessness. Much of the research on the inter-relationships among putatively adaptive and more maladaptive traits of psychopathy has focused on the factor structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) and its revision, the Psychopathic Personality Inventory – Revised (PPI-R). These instruments include content scales that have coalesced to form 2 higher-order factors in some (but not all) prior studies: Fearless Dominance and Self-Centered Impulsivity. Given the inconsistencies in prior research, we performed a meta- analytic factor analysis of the 8 content scales from these instruments (total N > 18,000) and found general support for these 2 dimensions in community samples. The structure among offender samples (e.g., prisoners, forensic patients) supported a three-factor model in which the Fearlessness content scale uniquely loaded onto Self-centered Impulsivity (rather than Fearless Dominance). There were also indications that the Stress Immunity content scale had different relations to the other PPI scales in offender versus community samples. -

Validity: Theoretical Basis Importance of Validity

Psychological Measurement mark.hurlstone @uwa.edu.au Validity Validity: Theoretical Basis Importance of Validity Classic & Contemporary Approaches PSYC3302: Psychological Measurement and Its Trinitarian View Unitary View Applications Test Content Internal Structure Response Processes Mark Hurlstone Associations With Univeristy of Western Australia Other Variables Consequences of Testing Other Week 5 Perspectives Reliability & Validity [email protected] Psychological Measurement Learning Objectives Psychological Measurement mark.hurlstone @uwa.edu.au Validity • Introduction to the concept of validity Importance of Validity • Overview of the theoretical basis of validity: Classic & Contemporary 1 Trinitarian view of validity Approaches Trinitarian View 2 Unitary view of validity Unitary View Test Content • Alternative perspectives on validity Internal Structure Response Processes • Contrasting validity and reliability Associations With Other Variables Consequences of Testing Other Perspectives Reliability & Validity [email protected] Psychological Measurement Validity in Everyday Usage Psychological Measurement mark.hurlstone @uwa.edu.au • In everyday language, we say something is valid if it is Validity sound, meaningful, or supported by evidence Importance of Validity • e.g., we may speak of a valid theory, a valid argument, Classic & or a valid reason Contemporary Approaches • In legal terminology, lawyers say something is valid if it is Trinitarian View Unitary View "executed with the proper formalities"—such as a valid -

Criterion-Referenced Measurement for Educational Evaluation and Selection

Criterion-Referenced Measurement for Educational Evaluation and Selection Christina Wikström Department of Educational Measurement Umeå University No. 1 Department of Educational Measurement Umeå University Thesis 2005 Printed by Umeå University March 2005 © Christina Wikström ISSN 1652-9650 ISBN 91-7305-865-3 Abstract In recent years, Sweden has adopted a criterion-referenced grading system, where the grade outcome is used for several purposes, but foremost for educational evaluation on student- and school levels as well as for selection to higher education. This thesis investigates the consequences of using criterion-referenced measurement for both educational evaluation and selection purposes. The thesis comprises an introduction and four papers that empirically investigate school grades and grading practices in Swedish upper secondary schools. The first paper investigates the effect of school competition on the school grades. The analysis focuses on how students in schools with and without competition are ranked, based on their grades and SweSAT scores. The results show that schools that are exposed to competition tend to grade their students higher than other schools. This effect is found to be related to the use of grades as quality indicators for the schools, which means that schools that compete for their students tend to be more lenient, hence inflating the grades. The second paper investigates grade averages over a six-year period, starting with the first cohort who graduated from upper secondary school with a GPA based on criterion-referenced grades. The results show that grades have increased every year since the new grading system was introduced, which cannot be explained by improved performances, selection effects or strategic course choices. -

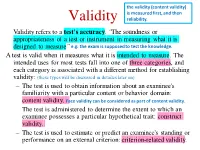

Validity (Content Validity) Is Measured First, and Then Validity Reliability

the validity (content validity) is measured first, and then Validity reliability. Validity refers to a test's accuracy. “The soundness or appropriateness of a test or instrument in measuring what it is designed to measure” e.g: the exam is supposed to test the knowledge. A test is valid when it measures what it is intended to measure. The intended uses for most tests fall into one of three categories, and each category is associated with a different method for establishing validity: (these types will be discussed in detailes later on) – The test is used to obtain information about an examinee's familiarity with a particular content or behavior domain: content validity. Face validity can be considered as part of content validity. – The test is administered to determine the extent to which an examinee possesses a particular hypothetical trait: construct validity. – The test is used to estimate or predict an examinee's standing or performance on an external criterion: criterion-related validity. Types of Experimental Validity • Internal – Is the experimenter measuring the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable? • External – Can the results be generalised to the wider population? There are 4 types of validity (Analysis done without 3) (analyzed statistically by SPSS) SPSS (manually)) 4) Criterion 1) 2) Reliability and validity are strongly related to each other. Validity of Measurement • Meaning analysis: the process of attaching meaning to concepts – Face validity – Content validity • Empirical analysis: how well our procedures (operational definition) accurately observe what we want to measure – Criterion validity. – Construct validity Done before content validity and it’s not Face Validity performed alone. -

The Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised

The Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised: Evaluation of Its Psychometric Properties, Incremental Validity, and Moderating Effects of Gender in a Correctional Sample by Natalia L. Nikolova M.A. (Psychology), Simon Fraser University, 2009 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Psychology Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Natalia L. Nikolova 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2013 Approval Name: Natalia L. Nikolova Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (Psychology) Title of Thesis: The Psychopathic Personality Inventory-Revised: Evaluation of Its Psychometric Properties, Incremental Validity, and Moderating Effects of Gender in a Correctional Sample Examining Committee: Chair: Robert Ley Associate Professor Kevin S. Douglas Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Stephen D. Hart Supervisor Professor Marlene M. Moretti Supervisor Professor William Glackman Internal Examiner Associate Professor School of Criminology Martin Sellbom External Examiner Assistant Professor Department of Psychology University of Alabama Date Defended/Approved: May 10, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Ethics Statement The author, whose name appears on the title page of this work, has obtained, for the research described in this work, either: a. human research ethics approval from the Simon Fraser University Office of Research Ethics, or b. advance approval of the animal care protocol from the University Animal Care Committee of Simon Fraser University; or has conducted the research c. as a co-investigator, collaborator or research assistant in a research project approved in advance, or d. as a member of a course approved in advance for minimal risk human research, by the Office of Research Ethics. A copy of the approval letter has been filed at the Theses Office of the University Library at the time of submission of this thesis or project. -

Lecture 5: Principles of Psychometrics: Validity I

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License. Your use of this material constitutes acceptance of that license and the conditions of use of materials on this site. Copyright 2006, The Johns Hopkins University and William Eaton. All rights reserved. Use of these materials permitted only in accordance with license rights granted. Materials provided “AS IS”; no representations or warranties provided. User assumes all responsibility for use, and all liability related thereto, and must independently review all materials for accuracy and efficacy. May contain materials owned by others. User is responsible for obtaining permissions for use from third parties as needed. Statistics in Psychosocial Research Lecture 5 Validity I Lecturer: William Eaton Validity The degree to which a test, scale, or assessment measures what it is supposed to measure. Outline • Face Validity • Content Validity • Construct Validity •Internal •External • Criterion Validity • Concurrent • Predictive • Validity and reliability • Validity and utility Classical Test Theory and Reliability: x = Tx + e The observed score equals the true score plus random measurement error Validity x = Tx + es + er The observed score equals the true score plus systematic error (bias) plus random measurement error Face Validity Does the item seem right? CESD: Depression: “I felt depressed” MMPI: Schizophrenia: “I believe in God” • Increases motivation among respondents • Reduces dissatisfaction among respondents • Enhances credibility of results • Improves public relations Face Validity: IQ Test Example 1. What would be the next number in this series? 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 5 ... 8 ... 13 ... 21 ... 34 ... ?? 47 53 55 62 65 I don't know Face Validity: IQ Test Example 2. -

Checklist to Operationalize Measurement Characteristics of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures David O

Francis et al. Systematic Reviews (2016) 5:129 DOI 10.1186/s13643-016-0307-4 METHODOLOGY Open Access Checklist to operationalize measurement characteristics of patient-reported outcome measures David O. Francis1,2,3*, Melissa L. McPheeters3,4,5, Meaghan Noud1, David F. Penson2,4,6,7 and Irene D. Feurer2,8 Abstract Background: The purpose of this study was to advance a checklist of evaluative criteria designed to assess patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures’ developmental measurement properties and applicability, which can be used by systematic reviewers, researchers, and clinicians with a varied range of expertise in psychometric measure development methodology. Methods: A directed literature search was performed to identify original studies, textbooks, consensus guidelines, and published reports that propose criteria for assessing the quality of PRO measures. Recommendations from these sources were iteratively distilled into a checklist of key attributes. Preliminary items underwent evaluation through 24 cognitive interviews with clinicians and quantitative researchers. Six measurement theory methodological novices independently applied the final checklist to assess six PRO measures encompassing a variety of methods, applications, and clinical constructs. Agreement between novice and expert scores was assessed. Results: The distillation process yielded an 18-item checklist with six domains: (1) conceptual model, (2) content validity, (3) reliability, (4) construct validity, (5) scoring and interpretation, and (6) respondent burden and presentation. With minimal instruction, good agreement in checklist item ratings was achieved between quantitative researchers with expertise in measurement theory and less experienced clinicians (mean kappa 0.70; range 0.66–0.87). Conclusions: We present a simplified checklist that can help guide systematic reviewers, researchers, and clinicians with varied measurement theory expertise to evaluate the strengths and weakness of candidate PRO measures’ developmental properties and the appropriateness for specific applications. -

Understanding Validity and Reliability in Classroom, School-Wide, Or District- Wide Assessments to Be Used in Teacher/Principal Evaluations

Understanding Validity and Reliability in Classroom, School-Wide, or District- Wide Assessments to be used in Teacher/Principal Evaluations Warren Shillingburg, PhD January 2016 Introduction As expectations have risen and requirements for student growth expectations have increased across the country, more and more school districts are being asked to develop local assessments and to use them as part of their teacher evaluation process. As districts explore this process, many are concerned about how they can develop local assessments that provide information to help students learn, provide evidence of a teacher’s contribution to student growth, and create reliable and valid assessments. These terms, validity and reliability, can be very complex and difficult for many educators to understand. If you are in a district that has access to appropriate software or the luxury of hiring a statistician to work through formulas, you are in the minority. Most districts cannot afford these expenses and struggle just to find the resources and time to create any assessment, giving very little time and attention to the concepts of validity and reliability. In light of this reality, some districts are choosing to simply not go this route and instead follow the premise that everyone contributes in some way to a child’s reading and math learning, and using the state or national assessments they currently have in these areas to apply to all teachers. Although there can be some validity in this assumption, with the state expectation that all LEAs shall ensure that multiple measures of student academic progress are used (Arizona State Board of Education, 2016) in a teacher/principal evaluation, districts will need to either find other assessments or develop their own assessments to meet this requirement. -

Understanding Validity for Classroom Teachers Slide # Title Presenter

Presenter’s Notes for PowerPoint: Understanding Validity for Classroom Teachers Slide # Presenter Notes Title This module provides teachers with basic information they need to understand what 1. Understanding validity is and why it is so important. Both reliability and validity are necessary for a Validity for teacher to make accurate inferences about student learning based on assessment Teachers results. For this reason, you need to study both this module and the Reliability module to understand quality assessment of student learning. This commonly used illustration provides visual metaphors of the concepts of Reliability and Validity. • The first target represents a valid and reliable assessment. The bull’s eye in the center of the target is shot with accuracy again and again. The correct target is being aimed at and it is being hit consistently. So validity (or the correct target) and reliability (or consistency) are evident. • The second target shows a scenario in which the shots are consistently striking 2. Validity & in a particular location – but it isn’t on the target. So if this were an assessment it Reliability would be reliable but not valid. • The third target shows another scenario. The shots are aimed at the target, but they are striking the target in a variety of locations and some aren’t hitting the target at all. There is no consistency or reliability and because of this there is also no validity. So it is important to remember that validity and reliability interact with and influence each other. Both are necessary for quality educational tests. This module answers the essential questions: • What is test validity? • What is content-related validity? • What is criterion-related validity? 3. -

On Biodata Construct Validity, Criterion-Related Validity, and Adverse Impact

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 On Biodata Construct Validity, Criterion-Related Validity, and Adverse Impact. Michelle Ann Dean Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Dean, Michelle Ann, "On Biodata Construct Validity, Criterion-Related Validity, and Adverse Impact." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6938. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6938 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.