The Validity of Measurement Methods, Text Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heterogeneous Versus Homogeneous Measures: a Meta-Analysis of Predictive Efficacy

HETEROGENEOUS VERSUS HOMOGENEOUS MEASURES: A META-ANALYSIS OF PREDICTIVE EFFICACY A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By SUZANNE L. DEAN M.S., Wright State University, 2008 _________________________________________ 2016 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL January 3, 2016 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE DISSERTATION PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Suzanne L. Dean ENTITLED Heterogeneous versus Homogeneous Measures: A Meta-Analysis of Predictive Efficacy BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy. _____________________________ Corey E. Miller, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________ Scott N. J. Watamaniuk, Ph.D. Graduate Program Director _____________________________ Robert E. W. Fyffe, Ph.D. Vice President for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Corey E. Miller, Ph.D. _____________________________ David LaHuis, Ph.D. _____________________________ Allen Nagy, Ph.D. _____________________________ Debra Steele-Johnson, Ph.D. COPYRIGHT BY SUZANNE L. DEAN 2016 ABSTRACT Dean, Suzanne L. Ph.D., Industrial/Organizational Psychology Ph.D. program, Wright State University, 2016. Heterogeneous versus Homogeneous Measures: A Meta-Analysis of Predictive Efficacy. A meta-analysis was conducted to compare the predictive validity and adverse impact of homogeneous and heterogeneous predictors on objective and subjective criteria for different sales roles. Because job performance is a dynamic and complex construct, I hypothesized that equally complex, heterogeneous predictors would have stronger correlations with objective and subjective criteria than homogeneous predictors. Forty-seven independent validation studies (N = 3,378) qualified for inclusion in this study. In general, heterogeneous predictors did not demonstrate significantly stronger correlations with the performance criteria than homogeneous predictors. -

On the Validity of Reading Assessments GOTHENBURG STUDIES in EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES 328

On the Validity of Reading Assessments GOTHENBURG STUDIES IN EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES 328 On the Validity of Reading Assessments Relationships Between Teacher Judgements, External Tests and Pupil Self-assessments Stefan Johansson ACTA UNIVERSITATIS GOTHOBURGENSIS LOGO GOTHENBURG STUDIES IN EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES 328 On the Validity of Reading Assessments Relationships Between Teacher Judgements, External Tests and Pupil Self-assessments Stefan Johansson ACTA UNIVERSITATIS GOTHOBURGENSIS LOGO © STEFAN JOHANSSON, 2013 ISBN 978-91-7346-736-0 ISSN 0436-1121 ISSN 1653-0101 Thesis in Education at the Department of Education and Special Education The thesis is also available in full text on http://hdl.handle.net/2077/32012 Photographer cover: Rebecka Karlsson Distribution: ACTA UNIVERSITATIS GOTHOBURGENSIS Box 222 SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Print: Ale Tryckteam, Bohus 2013 Abstract Title: On the Validity of Reading Assessments: Relationships Between Teacher Judgements, External Tests and Pupil Self-assessments Language: English with a Swedish summary Keywords: Validity; Validation; Assessment; Teacher judgements; External tests; PIRLS 2001; Self-assessment; Multilevel models; Structural Equation Modeling; Socioeconomic status; Gender ISBN: 978-91-7346-736-0 The purpose of this thesis is to examine validity issues in different forms of assessments; teacher judgements, external tests, and pupil self-assessment in Swedish primary schools. The data used were selected from a large-scale study––PIRLS 2001––in which more than 11000 pupils and some 700 teachers from grades 3 and 4 participated. The primary method used in the secondary analyses to investigate validity issues of the assessment forms is multilevel Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with latent variables. An argument-based approach to validity was adopted, where possible weaknesses in assessment forms were addressed. -

Questionnaire Validity and Reliability

Questionnaire Validity and reliability Department of Social and Preventive Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Outlines Introduction What is validity and reliability? Types of validity and reliability. How do you measure them? Types of Sampling Methods Sample size calculation G-Power ( Power Analysis) Research • The systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions • In the broadest sense of the word, the research includes gathering of data in order to generate information and establish the facts for the advancement of knowledge. ● Step I: Define the research problem ● Step 2: Developing a research plan & research Design ● Step 3: Define the Variables & Instrument (validity & Reliability) ● Step 4: Sampling & Collecting data ● Step 5: Analysing data ● Step 6: Presenting the findings A questionnaire is • A technique for collecting data in which a respondent provides answers to a series of questions. • The vehicle used to pose the questions that the researcher wants respondents to answer. • The validity of the results depends on the quality of these instruments. • Good questionnaires are difficult to construct; • Bad questionnaires are difficult to analyze. •Identify the goal of your questionnaire •What kind of information do you want to gather with your questionnaire? • What is your main objective? • Is a questionnaire the best way to go about collecting this information? Ch 11 6 How To Obtain Valid Information • Ask purposeful questions • Ask concrete questions • Use time periods -

Running Head: the STRUCTURE of PSYCHOPATHIC PERSONALITY 1 Evaluating the Structure of Psychopathic Personality Traits: a Meta-An

Running head: THE STRUCTURE OF PSYCHOPATHIC PERSONALITY 1 Evaluating the Structure of Psychopathic Personality Traits: A Meta-Analysis of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory Jared R. Ruchensky, John F. Edens, Katherine S. Corker, M. Brent Donnellan, Edward A. Witt, Daniel M. Blonigen Version: 11/17/2017 In press, Psychological Assessment © 2017, American Psychological Association. This paper is not the copy of record and may not exactly replicate the final, authoritative version of the article. The final article will be available, upon publication, via its DOI: 10.1037/pas0000520 THE STRUCTURE OF PSYCHOPATHIC PERSONALITY 2 Abstract Which core traits exemplify psychopathic personality disorder is a hotly debated question within psychology, particularly regarding the role of ostensibly adaptive traits such as stress immunity, social potency, and fearlessness. Much of the research on the inter-relationships among putatively adaptive and more maladaptive traits of psychopathy has focused on the factor structure of the Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) and its revision, the Psychopathic Personality Inventory – Revised (PPI-R). These instruments include content scales that have coalesced to form 2 higher-order factors in some (but not all) prior studies: Fearless Dominance and Self-Centered Impulsivity. Given the inconsistencies in prior research, we performed a meta- analytic factor analysis of the 8 content scales from these instruments (total N > 18,000) and found general support for these 2 dimensions in community samples. The structure among offender samples (e.g., prisoners, forensic patients) supported a three-factor model in which the Fearlessness content scale uniquely loaded onto Self-centered Impulsivity (rather than Fearless Dominance). There were also indications that the Stress Immunity content scale had different relations to the other PPI scales in offender versus community samples. -

“Is the Test Valid?” Criterion-Related Validity– 3 Classic Types Criterion-Related Validity– 3 Classic Types

“Is the test valid?” Criterion-related Validity – 3 classic types • a “criterion” is the actual value you’d like to have but can’t… Jum Nunnally (one of the founders of modern psychometrics) • it hasn’t happened yet and you can’t wait until it does claimed this was “silly question”! The point wasn’t that tests shouldn’t be “valid” but that a test’s validity must be assessed • it’s happening now, but you can’t measure it “like you want” relative to… • It happened in the past and you didn’t measure it then • does test correlate with “criterion”? -- has three major types • the specific construct(s) it is intended to measure Measure the Predictive Administer test Criterion • the population for which it is intended (e.g., age, level) Validity • the application for which it is intended (e.g., for classifying Concurrent Measure the Criterion folks into categories vs. assigning them Validity Administer test quantitative values) Postdictive Measure the So, the real question is, “Is this test a valid measure of this Administer test Validity Criterion construct for this population for this application?” That question can be answered! Past Present Future The advantage of criterion-related validity is that it is a relatively Criterion-related Validity – 3 classic types simple statistically based type of validity! • does test correlate with “criterion”? -- has three major types • If the test has the desired correlation with the criterion, then • predictive -- test taken now predicts criterion assessed later you have sufficient evidence for criterion-related -

Validity and Reliability in Social Science Research

Education Research and Perspectives, Vol.38, No.1 Validity and Reliability in Social Science Research Ellen A. Drost California State University, Los Angeles Concepts of reliability and validity in social science research are introduced and major methods to assess reliability and validity reviewed with examples from the literature. The thrust of the paper is to provide novice researchers with an understanding of the general problem of validity in social science research and to acquaint them with approaches to developing strong support for the validity of their research. Introduction An important part of social science research is the quantification of human behaviour — that is, using measurement instruments to observe human behaviour. The measurement of human behaviour belongs to the widely accepted positivist view, or empirical- analytic approach, to discern reality (Smallbone & Quinton, 2004). Because most behavioural research takes place within this paradigm, measurement instruments must be valid and reliable. The objective of this paper is to provide insight into these two important concepts, and to introduce the major methods to assess validity and reliability as they relate to behavioural research. The paper has been written for the novice researcher in the social sciences. It presents a broad overview taken from traditional literature, not a critical account of the general problem of validity of research information. The paper is organised as follows. The first section presents what reliability of measurement means and the techniques most frequently used to estimate reliability. Three important questions researchers frequently ask about reliability are discussed: (1) what Address for correspondence: Dr. Ellen Drost, Department of Management, College of Business and Economics, California State University, Los Angeles, 5151 State University Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90032. -

Validity: Theoretical Basis Importance of Validity

Psychological Measurement mark.hurlstone @uwa.edu.au Validity Validity: Theoretical Basis Importance of Validity Classic & Contemporary Approaches PSYC3302: Psychological Measurement and Its Trinitarian View Unitary View Applications Test Content Internal Structure Response Processes Mark Hurlstone Associations With Univeristy of Western Australia Other Variables Consequences of Testing Other Week 5 Perspectives Reliability & Validity [email protected] Psychological Measurement Learning Objectives Psychological Measurement mark.hurlstone @uwa.edu.au Validity • Introduction to the concept of validity Importance of Validity • Overview of the theoretical basis of validity: Classic & Contemporary 1 Trinitarian view of validity Approaches Trinitarian View 2 Unitary view of validity Unitary View Test Content • Alternative perspectives on validity Internal Structure Response Processes • Contrasting validity and reliability Associations With Other Variables Consequences of Testing Other Perspectives Reliability & Validity [email protected] Psychological Measurement Validity in Everyday Usage Psychological Measurement mark.hurlstone @uwa.edu.au • In everyday language, we say something is valid if it is Validity sound, meaningful, or supported by evidence Importance of Validity • e.g., we may speak of a valid theory, a valid argument, Classic & or a valid reason Contemporary Approaches • In legal terminology, lawyers say something is valid if it is Trinitarian View Unitary View "executed with the proper formalities"—such as a valid -

Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Assessing Depression Following Traumatic Brain Injury

J Head Trauma Rehabil Vol. 20, No. 6, pp. 501–511 c 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Assessing Depression Following Traumatic Brain Injury Jesse R. Fann, MD, MPH; Charles H. Bombardier, PhD; Sureyya Dikmen, PhD; Peter Esselman, MD; Catherine A. Warms, PhD; Erika Pelzer, BS; Holly Rau, BS; Nancy Temkin, PhD Objective: To test the validity and reliability of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for diag- nosing major depressive disorder (MDD) among persons with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Design: Prospective cohort study. Setting: Level I trauma center. Participants: 135 adults within 1 year of complicated mild, moderate, or severe TBI. Main Outcome Measures: PHQ-9 Depression Scale, Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (SCID). Results: Using a screening criterion of at least 5 PHQ-9 symptoms present at least several days over the last 2 weeks (with one being depressed mood or anhedonia) maximizes sensitivity (0.93) and specificity (0.89) while providing a positive predictive value of 0.63 and a negative predictive value of 0.99 when compared to SCID diagnosis of MDD. Pearson’s correlation between the PHQ-9 scores and other depression measures was 0.90 with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist depression subscale and 0.78 with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Test-retest reliability of the PHQ-9 was r = 0.76 and κ = 0.46 when using the optimal screening method. Conclusions: The PHQ-9 is a valid and reliable screening tool for detecting MDD in persons with TBI. -

Reliability and Validity of the Measurement--Two Concepts Which We Will Discuss Further Later in This Lab

INTRODUCTION Sociologist James A. Quinn states that the tasks of scientific method are related directly or indirectly to the study of similarities of various kinds of objects or events. One of the tasks of scientific method is that of classifying objects or events into categories and of describing the similar characteristics of members of each type. A second task is that of comparing variations in two or more characteristics of the members of a category. Indeed, it is the discovery, formulation, and testing of generalizations about the relations among selected variables that constitute the central task of scientific method. Fundamental to the performance of these tasks is a system of measurement. S.S. Stevens defines measurement as "the assignment of numerals to objects or events according to rules." This definition incorporates a number of important distinctions. It implies that if rules can be set up, it is theoretically possible to measure anything. Further, measurement is only as good as the rules that direct its application. The "goodness" of the rules reflects on the reliability and validity of the measurement--two concepts which we will discuss further later in this lab. Another aspect of definition given by Stevens is the use of the term numeral rather than number. A numeral is a symbol and has no quantitative meaning unless the researcher supplies it through the use of rules. The researcher sets up the criteria by which objects or events are distinguished from one another and also the weights, if any, which are to be assigned to these distinctions. This results in a scale. -

Criterion-Referenced Measurement for Educational Evaluation and Selection

Criterion-Referenced Measurement for Educational Evaluation and Selection Christina Wikström Department of Educational Measurement Umeå University No. 1 Department of Educational Measurement Umeå University Thesis 2005 Printed by Umeå University March 2005 © Christina Wikström ISSN 1652-9650 ISBN 91-7305-865-3 Abstract In recent years, Sweden has adopted a criterion-referenced grading system, where the grade outcome is used for several purposes, but foremost for educational evaluation on student- and school levels as well as for selection to higher education. This thesis investigates the consequences of using criterion-referenced measurement for both educational evaluation and selection purposes. The thesis comprises an introduction and four papers that empirically investigate school grades and grading practices in Swedish upper secondary schools. The first paper investigates the effect of school competition on the school grades. The analysis focuses on how students in schools with and without competition are ranked, based on their grades and SweSAT scores. The results show that schools that are exposed to competition tend to grade their students higher than other schools. This effect is found to be related to the use of grades as quality indicators for the schools, which means that schools that compete for their students tend to be more lenient, hence inflating the grades. The second paper investigates grade averages over a six-year period, starting with the first cohort who graduated from upper secondary school with a GPA based on criterion-referenced grades. The results show that grades have increased every year since the new grading system was introduced, which cannot be explained by improved performances, selection effects or strategic course choices. -

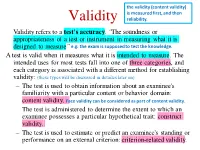

Validity (Content Validity) Is Measured First, and Then Validity Reliability

the validity (content validity) is measured first, and then Validity reliability. Validity refers to a test's accuracy. “The soundness or appropriateness of a test or instrument in measuring what it is designed to measure” e.g: the exam is supposed to test the knowledge. A test is valid when it measures what it is intended to measure. The intended uses for most tests fall into one of three categories, and each category is associated with a different method for establishing validity: (these types will be discussed in detailes later on) – The test is used to obtain information about an examinee's familiarity with a particular content or behavior domain: content validity. Face validity can be considered as part of content validity. – The test is administered to determine the extent to which an examinee possesses a particular hypothetical trait: construct validity. – The test is used to estimate or predict an examinee's standing or performance on an external criterion: criterion-related validity. Types of Experimental Validity • Internal – Is the experimenter measuring the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable? • External – Can the results be generalised to the wider population? There are 4 types of validity (Analysis done without 3) (analyzed statistically by SPSS) SPSS (manually)) 4) Criterion 1) 2) Reliability and validity are strongly related to each other. Validity of Measurement • Meaning analysis: the process of attaching meaning to concepts – Face validity – Content validity • Empirical analysis: how well our procedures (operational definition) accurately observe what we want to measure – Criterion validity. – Construct validity Done before content validity and it’s not Face Validity performed alone. -

Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Formative Measurement: a Mediator Perspective Xuequn Wang Murdoch University, Perth, AUS, [email protected]

Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 11 5-1-2015 Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Formative Measurement: A Mediator Perspective Xuequn Wang Murdoch University, Perth, AUS, [email protected] Brian F. French Washington State University, [email protected] Paul F. Clay Fort Lewis College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jmasm Recommended Citation Wang, Xuequn; French, Brian F.; and Clay, Paul F. (2015) "Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Formative Measurement: A Mediator Perspective," Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 11. DOI: 10.22237/jmasm/1430453400 Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jmasm/vol14/iss1/11 This Regular Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods Copyright © 2015 JMASM, Inc. May 2015, Vol. 14, No. 1, 83-106. ISSN 1538 − 9472 Convergent and Discriminant Validity with Formative Measurement: A Mediator Perspective Xuequn Wang Brian F. French Paul F. Clay Murdoch University Washington State University Fort Lewis College Perth, Australia Pullman, WA Durango, CO The ability to validate formative measurement has increased in importance as it is used to develop and test theoretical models. A method is proposed to gather convergent and discriminant validity evidence of formative measurement. Survey data is used to test the proposed method. Keywords: Causal indicators, formative measurement, construct validity, convergent validity, discriminant validity, mediator Introduction There has been a vigorous debate and discussion about the issues surrounding the application of formative measurement (Bollen, 2007; Howell et al., 2007a, 2007b; Petter et al., 2007) and how to validate this specific kind of measurement model (Hardin et al.