Roundtable Vol X, No. 18 (2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of London Ihesis

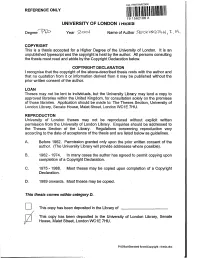

19 1562106X UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IHESIS DegreeT^D^ Year2o o\ Name of Author5&<Z <2 (NQ-To N , T. COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTON University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

H-Diplo Roundtable on Jeremi Suri, Henry Kissinger and the American

2008 Jeremi Suri. Henry Kissinger and the American Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, h-diplo July 2007. 368 pp. $27.95 (hardback). ISBN: 978-0- 674-02579-0. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Roundtable Editor: Thomas Maddux Volume IX, No. 7 (2008) Reviewers: Barbara Keys, Priscilla Roberts, James 17 April 2008 Sparrow, Yafeng Xia Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Kissinger-AmericanCentury- Roundtable.pdf Review by Yafeng Xia, Long Island University ixinge (Henry Kissinger in Chinese) has been a household name in China since 1971. He has visited China more than 40 times, and met with all Chinese top leaders from Mao JZedong, Zhou Enlai to the current Chinese leader Hu Jintao. In China, Kissinger is known Yafeng Xia is an assistant professor of East as a man of great wisdom. A quick check on Asian and Diplomatic history at Long Island the library holdings of Northeast Normal University, Brooklyn. He is the author of University in China shows a collection of more Negotiating with the Enemy: U.S.-China Talks during the Cold War, 1949-72 (Bloomington: than 50 books by or on Kissinger published in Indiana University Press, 2006). He has also Chinese, including the first two volumes of his published numerous articles in such publications memoirs (The third volume of his memoir, as Diplomacy & Statecraft, Journal of Cold War Years of Renewal has not yet been published in Studies, The Chinese Historical Review among Chinese) and many of his books. There are others. He is currently working on a monograph also several biographies of Kissinger and on the history of the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign doctoral dissertations on Kissinger in Chinese Affairs, tentatively entitled Burying the “Diplomacy of Humiliation”: New China’s from many different Chinese universities. -

H-Diplo Roundtable on Jeremi Suri, Henry Kissinger and the American

2008 h-diplo H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Volume IX, No. 7 (2008) 17 April 2008 Jeremi Suri. Henry Kissinger and the American Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, July 2007. 368 pp. $27.95 (hardback). ISBN: 978-0-674-02579-0. Roundtable Editor: Thomas Maddux Reviewers: Barbara Keys, Priscilla Roberts, James Sparrow, Yafeng Xia Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Kissinger-AmericanCentury- Roundtable.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University, Northridge.............................. 2 Review by Barbara Keys, University of Melbourne .................................................................. 8 Review by Priscilla Roberts, University of Hong Kong ............................................................ 16 Review by James T. Sparrow, University of Chicago............................................................... 23 Review by Yafeng Xia, Long Island University......................................................................... 30 Author’s Response by Jeremi Suri, University of Wisconsin-Madison ................................... 35 Copyright © 2008 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. IX, No 7 (2008) Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University, Northridge n his review Professor Yafeng Xia notes that Henry Kissinger is a most popular subject in China with over 50 books by or about Kissinger in Chinese at the library of the Northeast Normal University in China (as well as forthcoming doctoral dissertations). If you add this to the publications that Jeremi Suri cites on Kissinger (pp. -

Cathcart on George H.W. Bush China Diary, H-Diplo

2009 h-diplo H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Volume X, No. 18 (2009) 4 June 2009 Jeffrey A. Engel, ed. The China Diary of George H.W. Bush: The Making of a Global President. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2008. 544 pp. ISBN 978-0-691-13006-4. Roundtable Editors: Yafeng Xia and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web Editor: George Fujii Introduction by: Yafeng Xia, Long Island University Reviewers: Adam Cathcart, Pacific Lutheran University Ting Ni, Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota Priscilla Roberts, University of Hong Kong Guoqiang Zheng, Angelo State University Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-X-18.pdf Contents Introduction by Yafeng Xia, Long Island University .................................................................. 2 Review by Adam Cathcart, Pacific Lutheran University ............................................................ 6 Review by Ting Ni, Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota ...................................................... 10 Review by Priscilla Roberts, The University of Hong Kong ..................................................... 13 Review by Guoqiang Zheng, Angelo State University ............................................................. 28 Author’s Response by Jeffrey A. Engel, Texas A&M University .............................................. 31 Copyright © 2009 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate attribution to the author(s), web location, date of publication, H-Diplo, and H-Net: Humanities & Social Sciences Online. For other uses, contact the H-Diplo editorial staff at [email protected]. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews, Vol. X, No 18 (2009) Introduction by Yafeng Xia, Long Island University oon after President Richard Nixon’s trip to China in February 1972, there was a lull in Sino-American relations. -

And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

SINO-AMERICAN RELATIONS AND THE DIPLOMACY OF MODERNIZATION: 1966-1979 by MAO LIN (Under the Direction of William Stueck) ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the relations between the People’s Republic of China and the United States from the la te Johnson adm inistration to th e Carter adm inistration—a time period I call the “long 1970s.” To fully understa nd the development of Sino-American relations during this tim e period, we can not m erely fo cus on the strategic issues between the two countries such as the U S-PRC-USSR triangular diplomacy and ignore other non-strategic issues such as trade and cultural exchanges. Instead, we need to adopt a holistic approach by examining the discourse on China' s modernization, that is , how China' s modernization was perceived and debated by both countries' policy-makers and how the discourse on China' s modernization laid the foundation for improved relations between China and the United States. INDEX WORDS: US-Foreign Relations-China, Modernization SINO-AMERICAN RELATIONS AND THE DIPLOMACY OF MODERNIZATION: 1966-1979 by MAO LIN BA, Peking University, China, 1999 MA, Peking University, China, 2002 MA, The University of Georgia, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 Mao Lin All Rights Reserved SINO-AMERICAN RELATIONS AND THE DIPLOMACY OF MODERNIZATION: 1966-1979 by MAO LIN Major Professor: William Stueck Committee: Shane Hamilton Ari Levine Stephen Mihm Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia August 2010 DEDICATION TO MY FAMILY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank m y major advisor , Dr. -

Bulletin Supplement 1 2004

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC BULLETIN SUPPLEMENT 1 2004 AMERICAN DE´TENTE AND GERMAN OSTPOLITIK, 1969–1972 PREFACE David C. Geyer and Bernd Schaefer 1 CONTRIBUTORS The Berlin Wall, Ostpolitik and De´tente 5 Hope Harrison Superpower De´tente: US-Soviet Relations, 1969–1972 19 Vojtech Mastny The Path toward Sino-American Rapprochement, 1969–1972 26 Chen Jian “Thinking the Unthinkable” to “Make the Impossible Possible”: Ostpolitik, Intra-German Policy, and the Moscow Treaty, 1969–1970 53 Carsten Tessmer The Treaty of Warsaw: The Warsaw Pact Context 67 Douglas Selvage The Missing Link: Henry Kissinger and the Back-Channel Negotiations on Berlin 80 David C. Geyer “Washington as a Place for the German Campaign”: The U.S. Government and the CDU/CSU Opposition, 1969–1972 98 Bernd Schaefer “Take No Risks (Chinese)”: The Basic Treaty in the Context of International Relations 109 Mary E. Sarotte Ostpolitik: Phases, Short-Term Objectives, and Grand Design 118 Gottfried Niedhart Statements and Discussion 137 Egon Bahr Vyacheslav Kevorkov Helmut Sonnenfeldt James S. Sutterlin Kenneth N. Skoug Jonathan Dean PREFACE It may seem odd to begin a publication on “American De´tente and Ger- man Ostpolitik” by reflecting on Soviet foreign policy in 1969. Given the situation in Europe at the time, however, such reflections are anything but far-fetched. Richard Nixon and Willy Brandt, after all, developed their policies to “reduce the tensions” of the Cold War with Leonid Brezh- nev in mind. Moscow, meanwhile, structured its “Westpolitik” along similar lines, i.e., by focusing on both Washington and Bonn. This con- gruence of calculations was hardly accidental.