And Type the TITLE of YOUR WORK in All Caps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Historiography of the Origins of the Cold War

SOSHUM Jurnal Sosial dan Humaniora [Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities] Volume 9, Number 2, 2019 p-ISSN. 2088-2262 e-ISSN. 2580-5622 ojs.pnb.ac.id/index.php/SOSHUM/ A New Historiography of the Origins of the Cold War Adewunmi J. Falode 1 and Moses J. Yakubu 2 1 Department of History & International Studies, Lagos State University, Nigeria 2 Department of History & International Studies, University of Benin, Edo, Nigeria Lasu, Ojo Campus Ojo Local Government, 102101, Lagos, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Article Info ABSTRACT ________________ ___________________________________________________________________ History Articles The Cold War that occurred between 1945 and 1991 was both an Received: international political and historical event. As an international political event, Jan 2019 the Cold War laid bare the fissures, animosities, mistrusts, misconceptions Accepted: June 2019 and the high-stakes brinksmanship that has been part of the international Published: political system since the birth of the modern nation-state in 1648. As a July 2019 historical event, the Cold War and its end marked an important epoch in ________________ human social, economic and political development. The beginning of the Keywords: Cold War marked the introduction of a new form of social and political Cold War, Historiography, experiment in human relations with the international arena as its laboratory. Structuralist School, Its end signalled the end of a potent social and political force that is still Revisionist School, st Orthodox School shaping the course of the political relations among states in the 21 century. ____________________ The historiography of the Cold War has been shrouded in controversy. -

And the Dynamics of Memory in American Foreign Policy After the Vietnam War

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) ‘Whose Vietnam?’ - ‘Lessons learned’ and the dynamics of memory in American foreign policy after the Vietnam War Beukenhorst, H.B. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Beukenhorst, H. B. (2012). ‘Whose Vietnam?’ - ‘Lessons learned’ and the dynamics of memory in American foreign policy after the Vietnam War. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 2. Haig’s Vietnam and the conflicts over El Salvador When Ronald Reagan took over the White House in 1981, he brought with him a particular memory of the Vietnam War largely based on the pivotal war experiences of his generation: World War Two and the Korean War. -

Evelyn Goh, “Nixon, Kissinger, and the 'Soviet Card' in the US Opening T

H-Diplo Article Commentary: Kimball on Goh Evelyn Goh , “Nixon, Kissinger, and the ‘Soviet Card’ in the U.S. Opening to China, 1971- 1974”, Diplomatic History , Vol. 29, Issue 3 (June 2005): 475-502. Commentary by Jeffrey Kimball , Miami University of Ohio Published by H-Diplo on 28 October 2005 Evelyn Goh, a professor at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, describes how and asks why Henry Kissinger increasingly emphasized the Soviet military threat to China’s security in his negotiations with Beijing between 1971 and 1973. Drawing from the archival record and the literature on U.S. relations with the People’s Republic of China during the Nixon presidency, she traces Kissinger’s evolving policy through three phases: parallel détente with a tilt toward China (1971 to early 1972); “formal symmetry” but “tacit alliance” (mid 1972 to early 1973); and strategic shifts, attempted secret alliance, and stymied normalization (mid 1973 to 1974). Her purpose is to “understand and assess the nature and value of the Soviet card to the Nixon administration in the development of Sino- American relations” (477), because, she asserts, histories of triangular diplomacy have given more attention to Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger’s playing of the China card vis-à-vis the Soviet Union than of the Soviet card vis-à-vis China. Goh argues that in pursuing rapprochement Nixon and Kissinger “sought to manage . Chinese expectations” about improved Sino-American relations and dissuade Beijing from thinking that the U.S. aim was really that of playing “the China card in order to persuade the Soviet Union to negotiate détente with the United States” (479, 489). -

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 984 9 October 2020

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 984 9 October 2020 James G. Hershberg. “Soviet-Brazilian Relations and the Cuban Missile Crisis.” Journal of Cold War Studies 22:1 (Winter 2020): 175-209. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1162/jcws_a_00930. https://hdiplo.org/to/AR984 Editor: Diane Labrosse | Commissioning Editor: Michael E. Neagle | Production Editor: George Fujii Review by Felipe Loureiro, University of São Paulo f there is one single event that represented the dangers and perils of the Cold War, it was the US-Soviet confrontation over the deployment of Soviet ballistic missiles in Cuba in October 1962, which is best known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. The world had never been closer to a thermonuclear war than during that tense thirteen-day standoff between U.S.I President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. For decades, the Cuban Missile Crisis was studied as a classic example of a U.S.-Soviet bilateral confrontation, with Fidel Castro’s Havana playing at most a supporting role. Over the last two decades however, scholars have globalized and decentralized the crisis, showing that countries and societies of all parts of the world were not only strongly impacted by it, but also influenced, in multiple and sometimes key ways, how the superpowers’ standoff played out.1 As the geographic theater of the story, Latin America stood out as one of the main regions where the U.S.-Soviet stalemate produced major social and political impacts. Scholars have explored how President Kennedy’s 23 October public announcement about the existence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba sent shockwaves across the continent, prompting different reactions from state and non-state actors, including government crackdowns against local Communists and leftist groups, as well as a multilateral initiative for the establishment of a nuclear free zone in the hemisphere, which culminated years later with the signing of the Treaty of Tlatelolco in 1967.2 Latin American countries also played direct roles in the crisis itself. -

The Cold War and Washington's Policy of Containment

FORCED TO FLUTTER: The Cold War and WashingTon’s PoliCy of ConTainmenT Sunny Khanna (Karan) – 212509923 Ap/pols 4280 – sergei plekhanov Abstract: Most now regard Cold War as a surreal phase of a tremulous dream in which few leaders held the fate of millions within their grasp and juggled nuclear bombs for www.google.ca/hegel=p ortrait_fur1846 ideological purposes before the circus of humanity. The paper analysed Washington’s III. Conflict in Containment of Communism. The first part of Historical and ww.google.ca/george_kennan.lkw=sdgd=/soviet+usa quar the paper examined how George Kennan Philosophical Contexts I. Kennan’s Prophecy gave philosophical foundations to the In 1989, the Berlin Wall Kennan gave philosophical conflict. The second part surveyed the policy lay in ruined in rubble. foundations to the Cold of containment by arguing that America was Were people like war. eventually successful by renewing capitalist Reagan, Thatcher or Predicted that Soviet’s economies of Western Europe, by using soft Gorbachev Hegelian decline is inevitable. and hard force throughout the “neutral” “world-historical Soviet Union’s economy is Global South, and through tactical alliances individuals”? Or was inherently unsustainable. with other communist nations. The paper there unconscious Believed that American concluded by situating the Cold War in a development of history? government can historical context. Post-structural emphasis overwhelm the Soviets with Methodology: Tolstoy: “Life of nations strategic military and The interdisciplinary paper relied on both in not contained in few political prowess. primary and secondary sources. It consulted men.” Soviets system is “fragile memoirs and diaries of key politicians of the My conclusion: The and artificial in its era, and also their biographies. -

Kissinger's Triangular Diplomacy

Kissinger’s triangular diplomacy Veronika Lukacsova 2009 1 Kissinger’s triangular diplomacy BAKALÁRSKA PRÁCA Veronika Lukacsova Bratislavská medzinárodná škola liberálnych štúdií v Bratislave Bakalársky študijný program: Liberálne štúdiá Študijný odbor 3.1.6 Politológia Vedúci/školite ľ bakalárskej práce Samuel Abrahám, PhD BRATISLAVA 2009 2 Prehlásenie: Prehlasujem, že som bakalársku prácu vypracovala samostatne a použila uvedené pramene a literatúru. V Bratislave, d ňa 30.4. 2009 3 Po ďakovanie: Na tomto mieste by som rada po ďakoval svojmu konzultantovi Samuelovi Abrahámovi,PhD za cenné rady a pripomienky pri písaní tejto práce. 4 Abstract: The main idea of this bachelor’s thesis is to point out the phenomena of policy of triangular diplomacy as developed by Henry Kissinger, first Security Advisor and later the Secretary of State in Richard Nixon Administration. The aim of this thesis is to describe the main principles of Kissinger’s policies that included a new element: the policy of détente. After a brief characteristic of the history of balance of power, and comparing the 19th Century Europe to the 20th Century diplomacy, the thesis continues by describing the events which influenced the policy of triangular diplomacy. It also aims to show how Kissinger’s policies were influenced by the main protagonist of 19 th Century balance of power, Count Clemens von Metternich. Finally, the work focuses on the relationship between the United States, Soviet Union and China and the policy of détente in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Finally, the thesis deals with the successes and the failures of triangular diplomacy. 5 Content: 1.Introduction.......................................................................................7 1. -

The Myth of Nixon's Opening of China Nick Demaris

THE MYTH OF NIXON’S OPENING OF CHINA The Myth of Nixon’s Opening of China Nick DeMaris On February 21, 1972, Air Force One descended through Beijing’s early morning haze as the highly-trained pilots navigated the Boeing VC-137C, nicknamed the “Spirit of ‘76”, towards the runway. Inside sat the 37th President of the United States, Richard M. Nixon, nervously awaiting the imminent meetings with the leaders of the Communist Party of China, including Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai.1 In the context of Cold War-era international relations and geopolitics, perhaps the single most historically significant and decisive event was President Nixon’s establishment of official (and public) diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. His trip to Beijing in early 1972 marked the beginning of a certain rapprochement between these two countries and signaled the evolution of the relationships between China, the United States, and the Soviet Union. 1 Margaret MacMillan, Nixon and Mao: The Week that Changed the World (New York: Random House, 2007) 19. 82 RHODES HISTORICAL REVIEW In the aftermath of World War II, as the Japanese threat to China ceased to exist, the two competing factions within the country, the Guomindang led by Chiang Kai- Shek, and the Communists led by Mao Zedong, were able to focus their efforts and resources on defeating each other instead of defending against Japanese occupation. This resulted in a bloody civil war between the Guomindang, the government that led the Republic of China, and the People’s Liberation Army that lasted until the Communists claimed victory in 1950. -

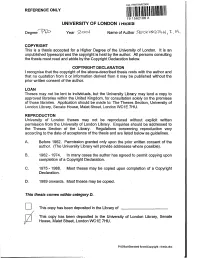

University of London Ihesis

19 1562106X UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IHESIS DegreeT^D^ Year2o o\ Name of Author5&<Z <2 (NQ-To N , T. COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTON University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 - 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Hold the Line Through 2035

HOLD THE LINE THROUGH 2035 A Strategy to Offset China’s Revisionist Actions and Sustain a Rules-based Order in the Asia-Pacific Gabriel Collins, J.D. Baker Botts Fellow in Energy & Environmental Regulatory Affairs, Center for Energy Studies, Baker Institute Andrew S. Erickson, Ph.D. Professor of Strategy, China Maritime Studies Institute, Naval War College November 2020 Hold the Line Through 2035 | 1 Disclaimer: This paper is designed to offer potential policy ideas, not advocate for specific private sector outcomes. Neither author has a financial stake involved or any conflict of interest pertaining to the subjects discussed. Acknowledgement: The authors wish to thank multiple anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. Their inputs made this a stronger, more useful piece. Any errors are the authors’ alone. Contact information: [email protected] and [email protected]. © 2020 by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researchers and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute, or the position of any organization with which the authors are affiliated. Gabriel Collins, J.D. Andrew S. Erickson, Ph.D. “Hold the Line Through 2035: A Strategy to Offset China’s Revisionist Actions and Sustain a Rules-based Order in the Asia-Pacific” https://doi.org/10.25613/4fzk-1v17 2 | Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Executive Summary • Between now and 2035, imposing costs on strategically unacceptable Chinese actions while also pursuing behind-the-scenes “defense diplomacy” with Beijing offers a sustainable path to influence PRC behavior and position the Indo-Asia- Pacific1 for continued prosperity and growth under a rules-based regional system. -

Nixon, Kissinger, and the “Soviet Card” in the U.S. Opening to China, 1971–1974*

evelyn goh Nixon, Kissinger, and the “Soviet Card” in the U.S. Opening to China, 1971–1974* The dramatic reconciliation with the People’s Republic of China in 1972 stands as one of Richard Nixon’s greatest achievements as the thirty-seventh president of the United States. While previous administrations had attempted minor modifications of the policy of containment and isolation of China, Nixon managed to negotiate a top-level reconciliation that would lead to normaliza- tion of relations in 1979.1 This rapprochement ended more than twenty years of Sino-American hostility and represented the most significant strategic shift of the Cold War era. It was intimately connected to U.S. relations with its super- power rival and the Nixon administration’s general policy of détente. In the writings of Nixon and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger—the key primary accounts of the policy change until recently—the central logic of the U.S.-China rapprochement was “triangular relations.” Within the context of the Sino-Soviet split, this entailed the opening of relations between the United States and China, bringing China into the realm of great power relations as a third vital power separate from the Soviet Union. The utility of triangular politics was derived from the expectation, accord- ing to Kissinger, that “in a subtle triangle of relations between Washington, Beijing and Moscow, we improve the possibilities of accommodations with each as we increase our options toward both.”2 The aim of pursuing better relations with both the PRC and the Soviet Union accorded with Nixon’s professed strat- egy of détente, to reduce international tensions and American overseas defense *The author would like to thank Rosemary Foot, Alastair Iain Johnston, Jeffrey Engel, Robert Schulzinger, and two anonymous referees for their comments and suggestions. -

Richard Nixon, Dtente, and the Conservative Movement, 1969-1974

Richard Nixon, Détente, and the Conservative Movement, 1969-1974 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By ERIC PATRICK GILLILAND B.A., Defiance College, 2004 2006 Wright State University iii WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES 12/13/06 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Eric Gilliland ENTITLED Richard Nixon, Détente, and the Conservative Movement, 1969-1974 BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. ______________________________ Jonathan Reed Winkler, PhD Thesis Advisor ______________________________ Edward F. Haas Department Chair Committee on Final Examination ________________________________ Jonathan Reed Winkler, PhD. ________________________________ Edward F. Haas, PhD. ________________________________ Kathryn B. Meyer ________________________________ Joseph F. Thomas, Jr., Ph.D. Dean, School of Graduate Studies iv ABSTRACT Gilliland, Eric Patrick. M.A., Department of History, Wright State University, 2006. Richard Nixon, Détente, and the Conservative Movement. This work examines the relationship between President Richard Nixon and the American conservative movement (1969-1974). Nixon’s anti-communist persona proved pivotal in winning the 1968 Republican Party’s and winning over the conservative base. The foreign policies orchestrated by Nixon and his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, however, which sought to reduce tensions with China and the Soviet Union, infuriated the conservatives. In 1971-72, they suspended their support of the administration and even drafted their own candidate, the Ohio congressman John Ashbook, to challenge Nixon in the 1972 primary campaign. Although the Ashbrook campaign had a minimal impact, it set a precedent for conservative opposition to détente in the 1970s and 1980s. -

H-Diplo Roundtable on Jeremi Suri, Henry Kissinger and the American

2008 Jeremi Suri. Henry Kissinger and the American Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, h-diplo July 2007. 368 pp. $27.95 (hardback). ISBN: 978-0- 674-02579-0. H-Diplo Roundtable Reviews www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Roundtable Editor: Thomas Maddux Volume IX, No. 7 (2008) Reviewers: Barbara Keys, Priscilla Roberts, James 17 April 2008 Sparrow, Yafeng Xia Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Kissinger-AmericanCentury- Roundtable.pdf Review by Yafeng Xia, Long Island University ixinge (Henry Kissinger in Chinese) has been a household name in China since 1971. He has visited China more than 40 times, and met with all Chinese top leaders from Mao JZedong, Zhou Enlai to the current Chinese leader Hu Jintao. In China, Kissinger is known Yafeng Xia is an assistant professor of East as a man of great wisdom. A quick check on Asian and Diplomatic history at Long Island the library holdings of Northeast Normal University, Brooklyn. He is the author of University in China shows a collection of more Negotiating with the Enemy: U.S.-China Talks during the Cold War, 1949-72 (Bloomington: than 50 books by or on Kissinger published in Indiana University Press, 2006). He has also Chinese, including the first two volumes of his published numerous articles in such publications memoirs (The third volume of his memoir, as Diplomacy & Statecraft, Journal of Cold War Years of Renewal has not yet been published in Studies, The Chinese Historical Review among Chinese) and many of his books. There are others. He is currently working on a monograph also several biographies of Kissinger and on the history of the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign doctoral dissertations on Kissinger in Chinese Affairs, tentatively entitled Burying the “Diplomacy of Humiliation”: New China’s from many different Chinese universities.